Prudence Heward was a central figure in the Montreal art world from the 1920s through the 1940s and participated in the avant-garde art movement in Canada in the early twentieth century. Primarily known for her figurative paintings, she employed principles of European modernism, such as expressionistic colour, in her art. In the 1970s feminist art historians rediscovered her work, and more recently, scholars have critiqued her depictions of black women.

The Beaver Hall Group

Although not officially a member of the Beaver Hall Group, Heward was close to several of its nineteen members, including Sarah Robertson (1891–1948) and Mabel Lockerby (1882–1976). The Beaver Hall Group (also known as the Beaver Hall Hill Group) was comprised of artists who shared studio space at 305 Beaver Hall Hill in Montreal and exhibited together. Heward, born into a wealthy family, had her own studio on the top floor of a house on Peel Street, where she lived with her mother.

The group, which had no manifesto, was formed in 1920 and is significant in the history of Canadian painting for being the first artists’ collective in which women played key roles. Previously women who painted were largely regarded as amateurs rather than as professional artists. Notably the Beaver Hall Group was the first artists’ association in Canada to consist mostly of women who not only painted but also exhibited and sold their work. While there is some disagreement about how long the group lasted, most scholars agree that it disbanded in 1921 or 1922, because of financial problems.

Exhibiting with the Group of Seven

Despite Heward’s commitment to painting people, an art critic for the Montreal Gazette wrote in 1932 that Heward was known as “an adopted daughter of the Group of Seven” because she had exhibited with the landscape painters on three occasions. This description may not be entirely accurate, but she exhibited Jones Creek, 1928, and Tonina, 1928, with the Group of Seven in 1928 at the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario). Her paintings At the Theatre, 1928, and The Emigrants, 1928, were included in the Group’s 1930 exhibition at the Art Gallery of Toronto and at the Art Association of Montreal. Three works—Girl Under a Tree, 1931; Cagnes, c.1930; and Street in Cagnes, c. 1930—were included in the Group of Seven show at the Art Gallery of Toronto in 1931.

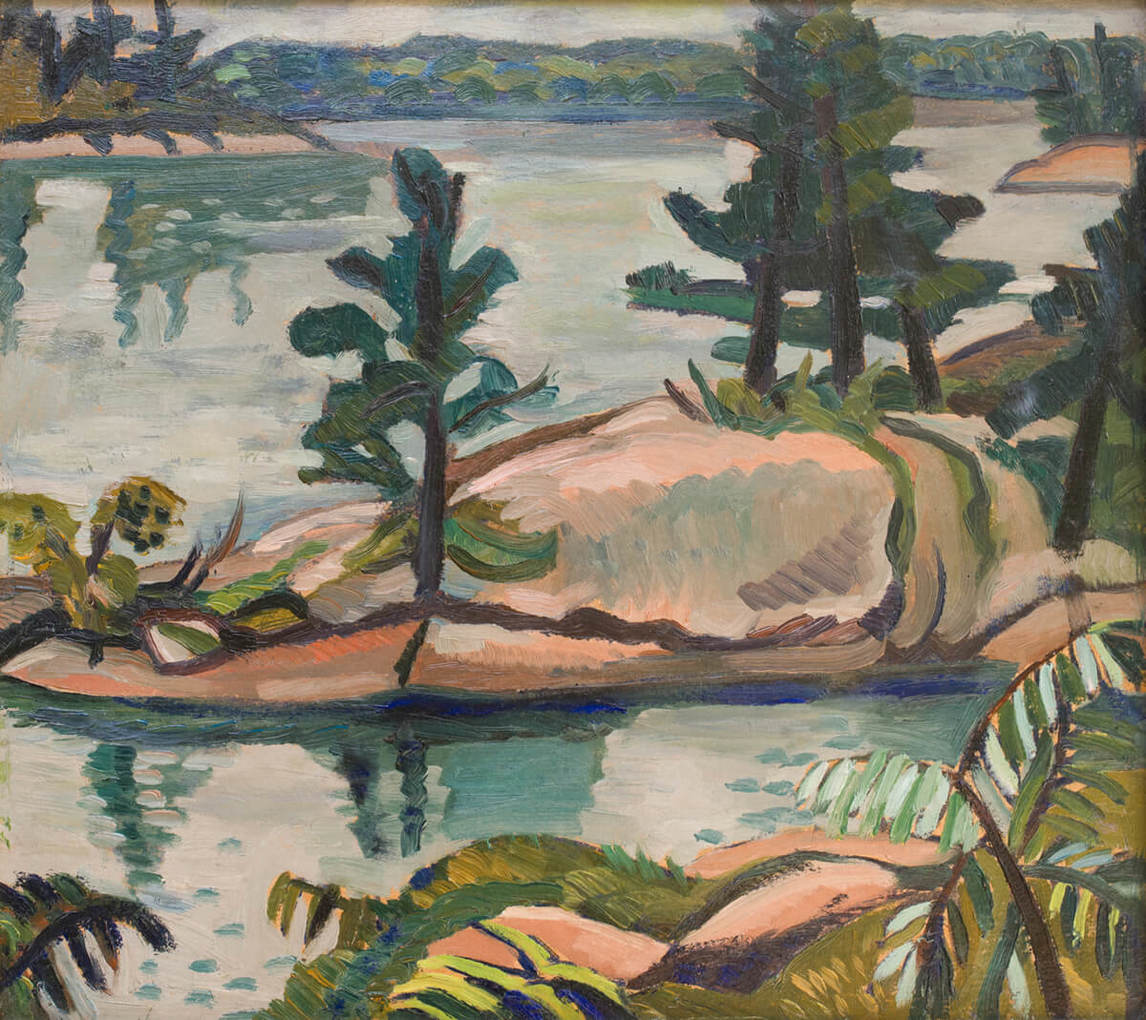

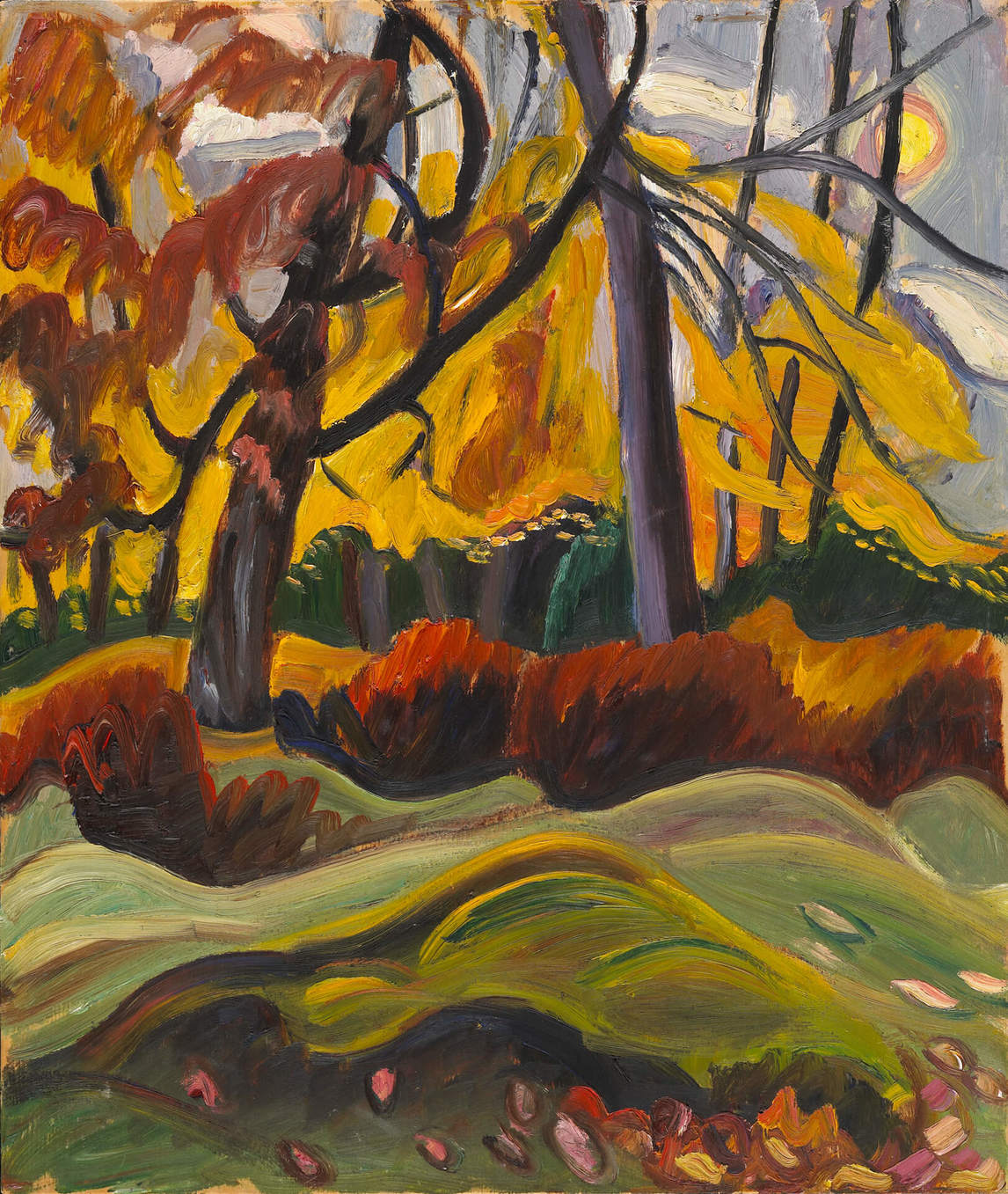

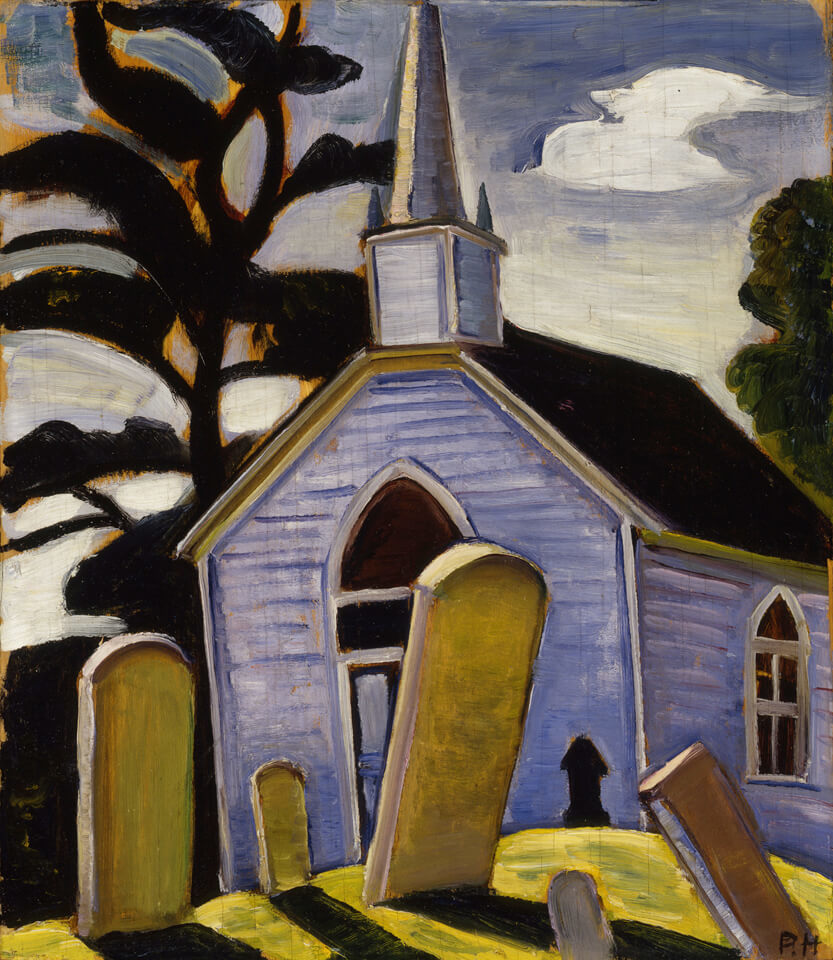

A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974) admired Heward’s work, and he wrote the catalogue essay for her 1948 memorial exhibition, a major touring show. Despite her contact with the Group of Seven, Heward continued to focus on the human subject until she stopped painting in 1945 because of illness, though she did produce several landscapes during her lifetime, including Laurentian Landscape, c. 1935, and The North River, Autumn, 1935. She often painted en plein air, on wood panels, recalling the technique of French Impressionists such as Claude Monet (1840–1926). She liked to go on sketching trips in Ontario and Quebec with fellow artists, including A.Y. Jackson, Anne Savage (1896–1971), and Sarah Robertson (1891–1948).

Race and Gender

Most of Heward’s paintings represent women, both black and white subjects. She also produced several paintings portraying Indigenous female subjects, such as Indian Head, 1936. In her titles that do not identify sitters by name, she often used the term “girl” rather than “woman.” In the early twentieth century, gendered language was not as critically examined as it is now, and this was standard usage until the 1970s.

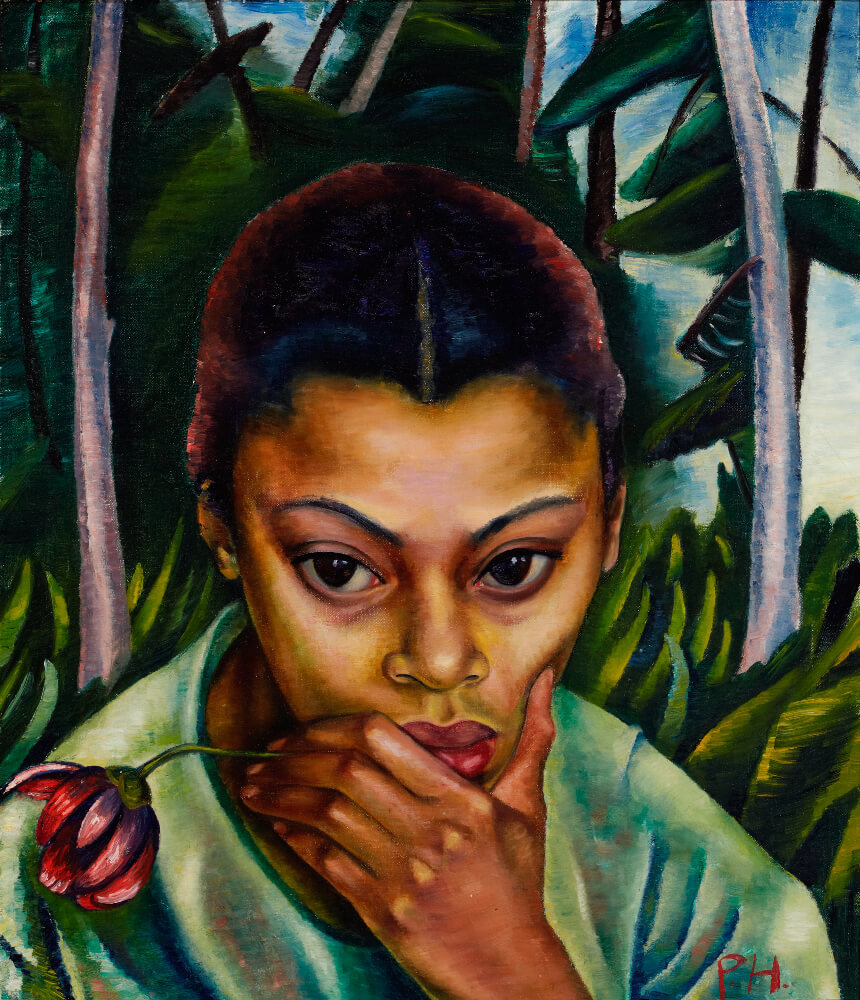

We do not know for sure Heward’s motivations for choosing to paint black women, but her decision to produce several paintings of them, as well as of a young black girl (Clytie, 1938), indicates that she had a particular interest in the black female subject. Whether this interest was primarily formal (in that painting black women allowed her to experiment with different colours of paint), altruistic (calling attention to issues of race in Canadian society), a result of the availability of black models in early twentieth-century Montreal (many of whom worked as domestics and needed the additional money), or a combination of these factors, art historians have perceived these works in a range of ways. There were sometimes hostile, indeed racist, reactions to Heward’s depictions of naked black women, focusing on their ostensibly unattractive body language, such as hunched shoulders and “melancholy” expressions. Significantly Heward’s library included George Bernard Shaw’s The Adventures of the Black Girl in Her Search for God (1932), which contains engravings by John Farleigh, indicating her interest in the black female subject perhaps as early as 1932.

Heward’s representations of black and Indigenous girls and women speak to issues of both gender and race in early twentieth-century Canada. Art historian Charmaine Nelson asks, “How could one seriously interpret Prudence Heward’s Dark Girl (1935), a lone naked and melancholic black female surrounded by tropicalized foliage, without discussing the evocation of Africa as the ‘dark continent’ and without mentioning Heward’s seeming preoccupation with black women and girls as subjects for other paintings like Hester (1937), Clytie (1938), Girl in the Window (1941), and Negress with Flower (n.d.)?”

Nelson notes that in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, white Canadian artists sometimes painted black women who worked as domestics and as models in art schools and community centres. Given that Heward was a white woman from an affluent Montreal family, her relationships with black female models were necessarily informed by issues of social class as well as of gender and race. Heward’s paintings of female subjects—white, black, and Indigenous—demand critical theoretical readings that draw on the work of feminist and post-colonial scholars concerned with visual material.

Painting Women

Heward’s focus on the female subject has led to her comparison to the French Impressionist Berthe Morisot (1841–1895). Unlike Morisot, Heward painted women independently of children, as shown in the paintings of her niece Ann and her friend Eleanor where women are depicted as solitary, not as mothers. This may be a reflection of how women were beginning to chafe against expectations regarding marriage and raising a family in the early twentieth century. The majority of the women associated with the Beaver Hall Group, for example, except for Lilias Torrance Newton (1896–1980), remained unmarried. This resulted in greater freedom and more time to dedicate to their art. In not painting women as mothers, Heward illuminated a shift in the social landscape of Canada while reflecting her own experience as a modern woman.

In the early 1920s, Heward painted bust portraits of solitary, serious women, such as Eleanor, 1924, and Miss Lockerby, c. 1924. Mabel Lockerby (1882–1976) was also an artist, and she appeared again in Heward’s At the Café, c. 1929, wearing a ring on her right hand. The single woman alone in a café was a popular subject for artists in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Europe and North America, and Heward’s later representation of Lockerby seated at a café table is part of this lineage of images depicting modern women in modern spaces.

Feminism and Post-Colonialism

Feminist art history and post-colonial studies are useful methodologies for examining Heward’s work. In 1971 American feminist art historian Linda Nochlin wrote a provocative article titled “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” Her premise was not that there had been no talented women artists up to that point but rather that, because of systemic sexism in art-historical studies and curatorship, female artists had been left out of the canon.

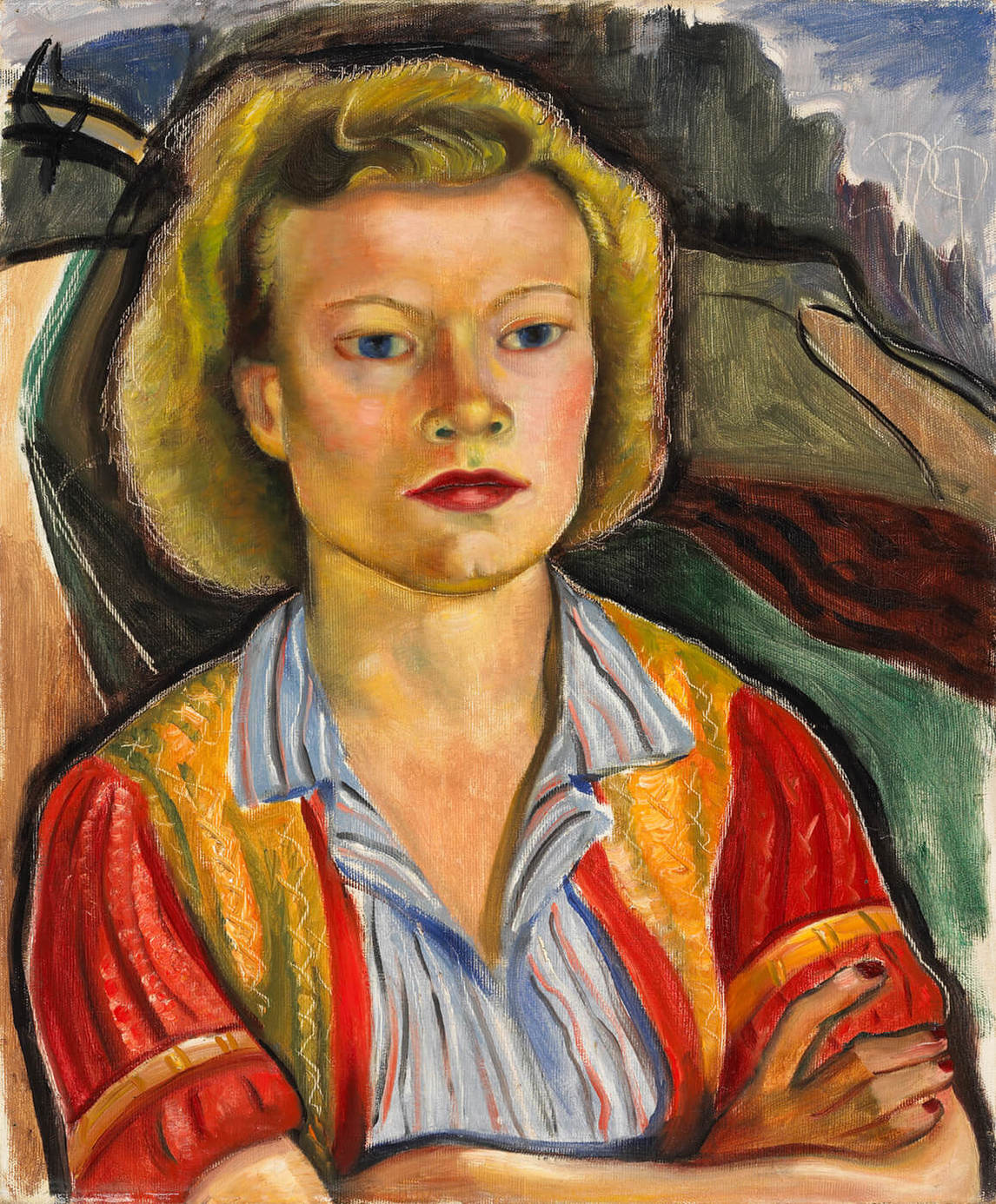

Heward was celebrated during her lifetime: her memorial exhibition in 1948 had been a critical and popular success, and she was included in a 1964 exhibition at the Continental Galleries in Montreal. And she was never completely forgotten or erased from the Canadian canon after her death. For instance, she was one of the very few women artists included in Dennis Reid’s A Concise History of Canadian Painting. His discussion centres on Heward’s Farmer’s Daughter, 1945, remarking upon the subject’s “vigorous individuality … bold, exciting, it is almost shocking in its sugar-acid colours and defiant anonymity.” However, she was not written about as often or as extensively as were her male contemporaries in histories of Canadian art.

One result of Nochlin’s article was the recuperation model of feminist art history: the rediscovery of historical women artists and the insertion of these artists into the art-historical canon through publications and exhibitions. The 1975 exhibition curated by Dorothy Farr and Natalie Luckyj at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre in Kingston, Ontario, From Women’s Eyes: Women Painters in Canada, which included work by Heward, was part of this trend. In 1986, Luckyj curated Expressions of Will: The Art of Prudence Heward at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre, which was accompanied by an exhibition catalogue, one of the first texts to focus on a sole Canadian woman artist.

Post-colonial theory provides another useful framework for thinking about Heward’s representations of black subjects. Significantly Heward produced very few paintings of white female nudes, whereas she produced several paintings that portray black women in various states of undress, such as Negress with Flower, n.d., and Negress with Sunflowers, c. 1936 (possibly the same model). Art historian Charmaine Nelson has critically examined Heward’s depictions of black women, but almost nothing has been written about Heward’s depiction of a young Indigenous girl in Indian Child, 1936, though important work has been done on visual representations of Indigenous women. This gap in the scholarship on Heward must be addressed by future art historians.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements