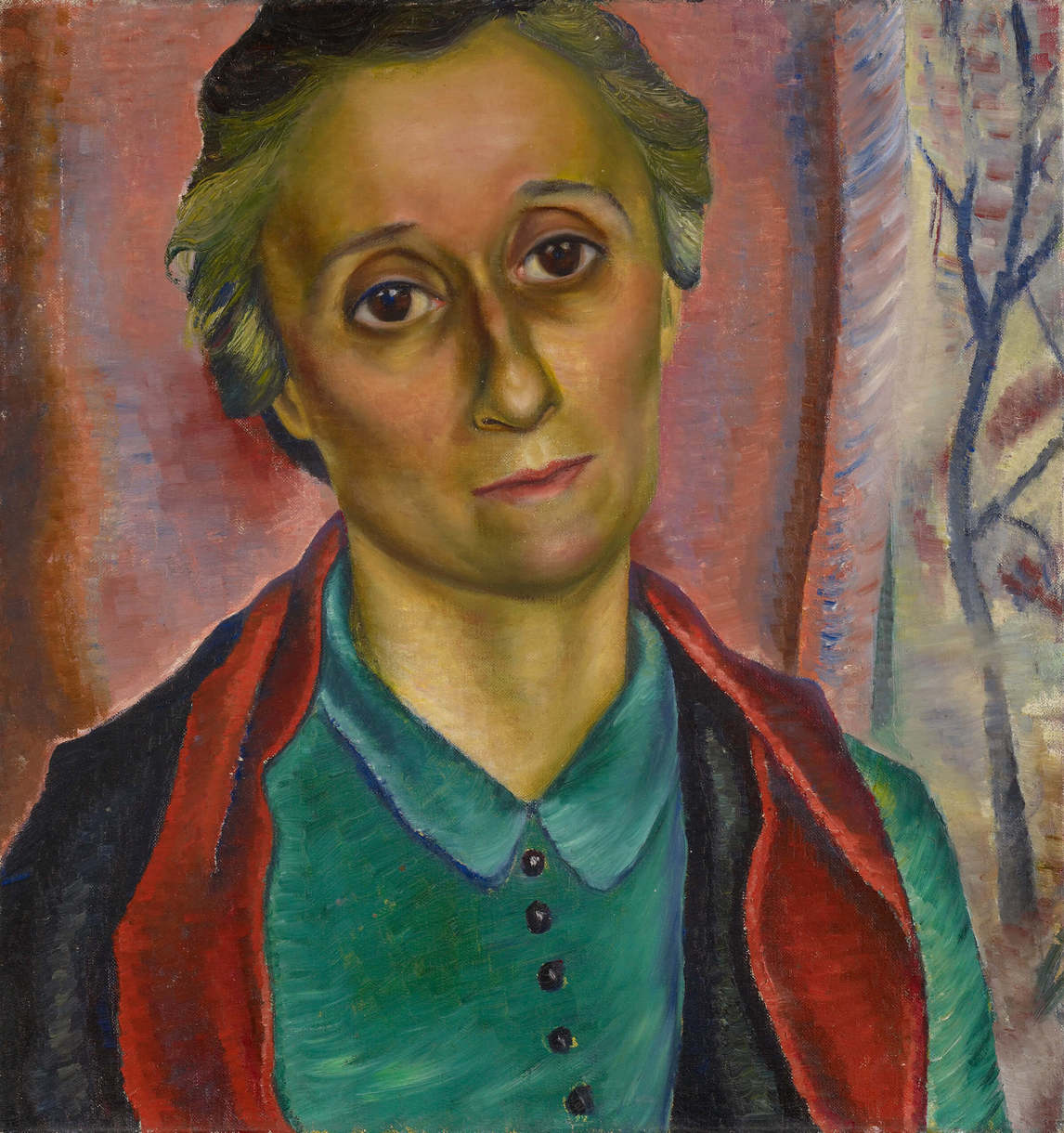

Celebrated for her sculptural forms, defiant figures, and expressionistic colours, Prudence Heward (1896–1947) created provocative representations of female subjects. She was affiliated with the Beaver Hall Group, the Canadian Group of Painters, and the Contemporary Arts Society, but also exhibited with the Group of Seven. After her death in 1947, the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, organized a memorial exhibition of her work, which toured across the country.

Early Years

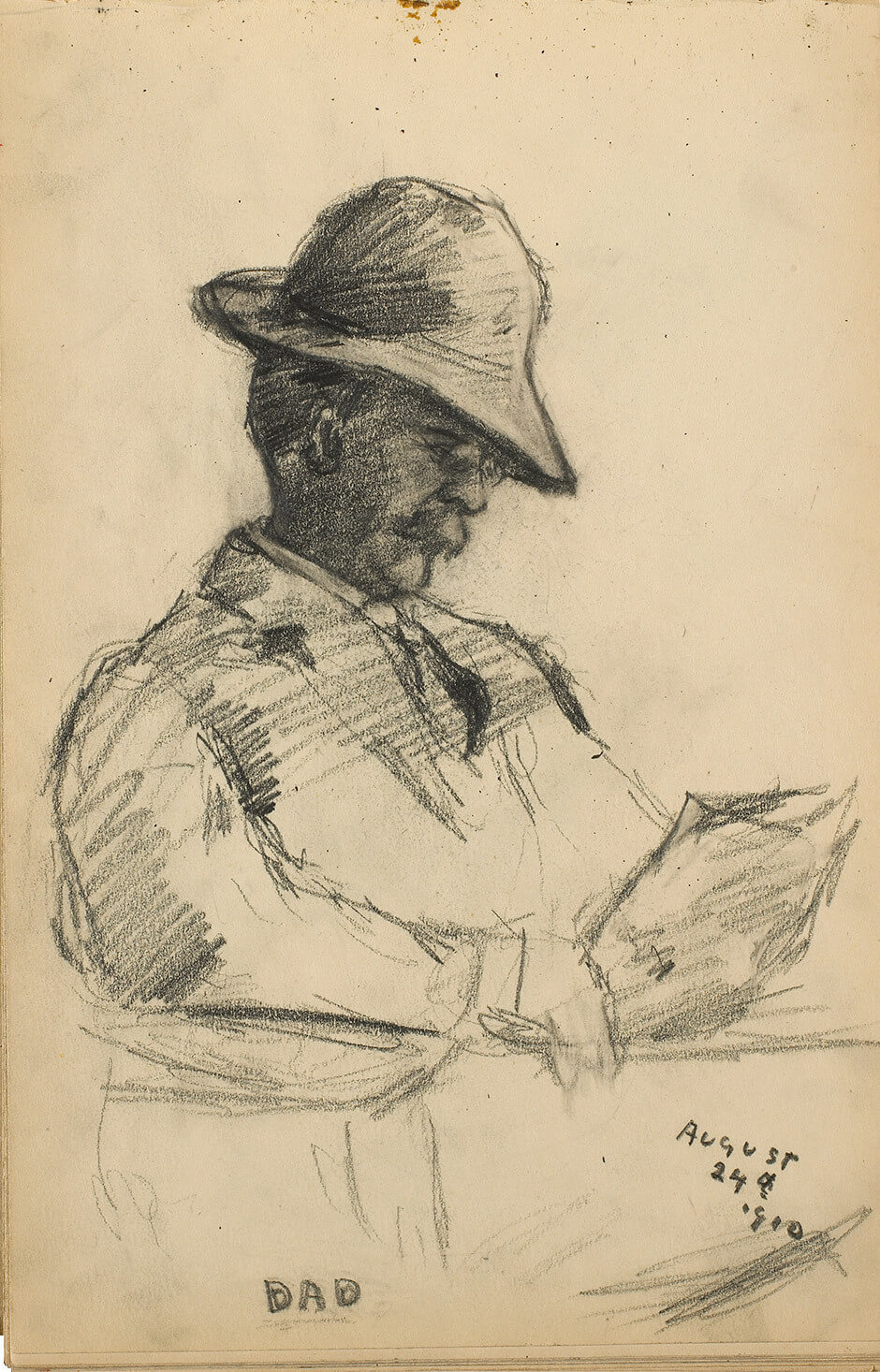

Efa Prudence Heward was born on July 2, 1896, into a wealthy Montreal family. She was the sixth of eight children born to Sarah Efa Jones and Arthur R.G. Heward, who worked for the Canadian Pacific Railway. The family lived in a large house in Montreal, summering at Fernbank, near Brockville, Ontario. Later in her life, Heward often went to Fernbank with artist friends, including A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974), Isabel McLaughlin (1903–2002), and Sarah Robertson (1891–1948), for sketching picnics.

Heward was a frail child and she suffered from asthma her whole life, the frequent attacks forcing her to cease painting for various lengths of time. She often wrote to McLaughlin about how these interruptions were both frustrating and discouraging. In a letter from May 17, 1935, she writes: “I was in bed for a week with hay fever. I’m just beginning to feel myself again; how these attacks keep pulling me back and down, no one knows how much.” During her childhood, her poor health led to periods of isolation, which helped prepare her for later in life when she would spend long stretches alone in her studio.

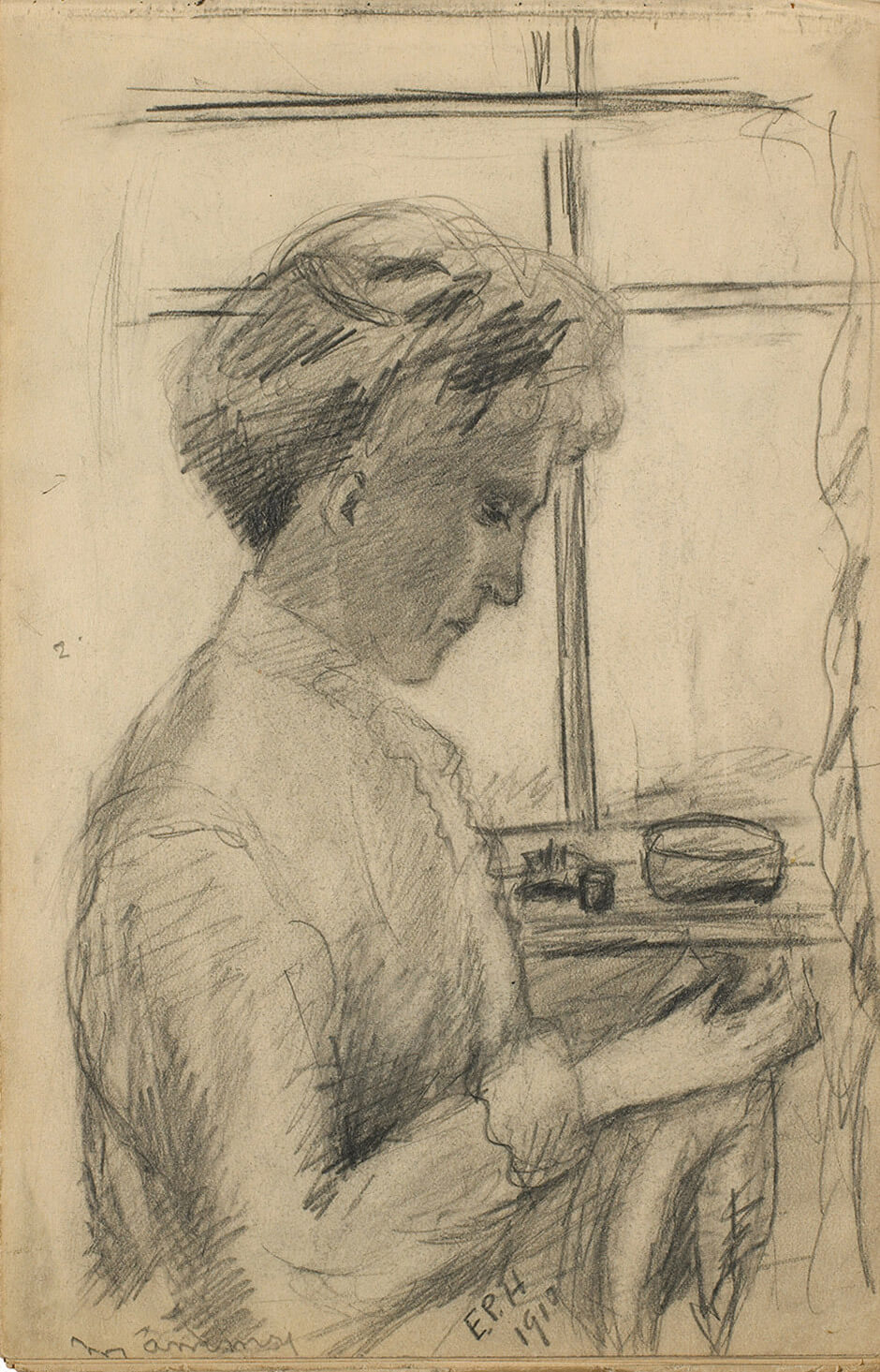

Heward first began taking drawing lessons at the age of twelve, at the Art Association of Montreal. Starting in 1912, when she was sixteen, the Heward family experienced a series of shocks that would lead her to temporarily stop making art. On May 16 her father died, and less than a week later, Heward’s sister Dorothy died in childbirth. Then another sister, Barbara, died in October at the age of twenty. The following year, her brother Jim contracted tuberculosis, though he recovered his health enough to enlist in the army. In 1914 Jim and Heward’s other brother, Chilion, went to Europe to fight in the First World War.

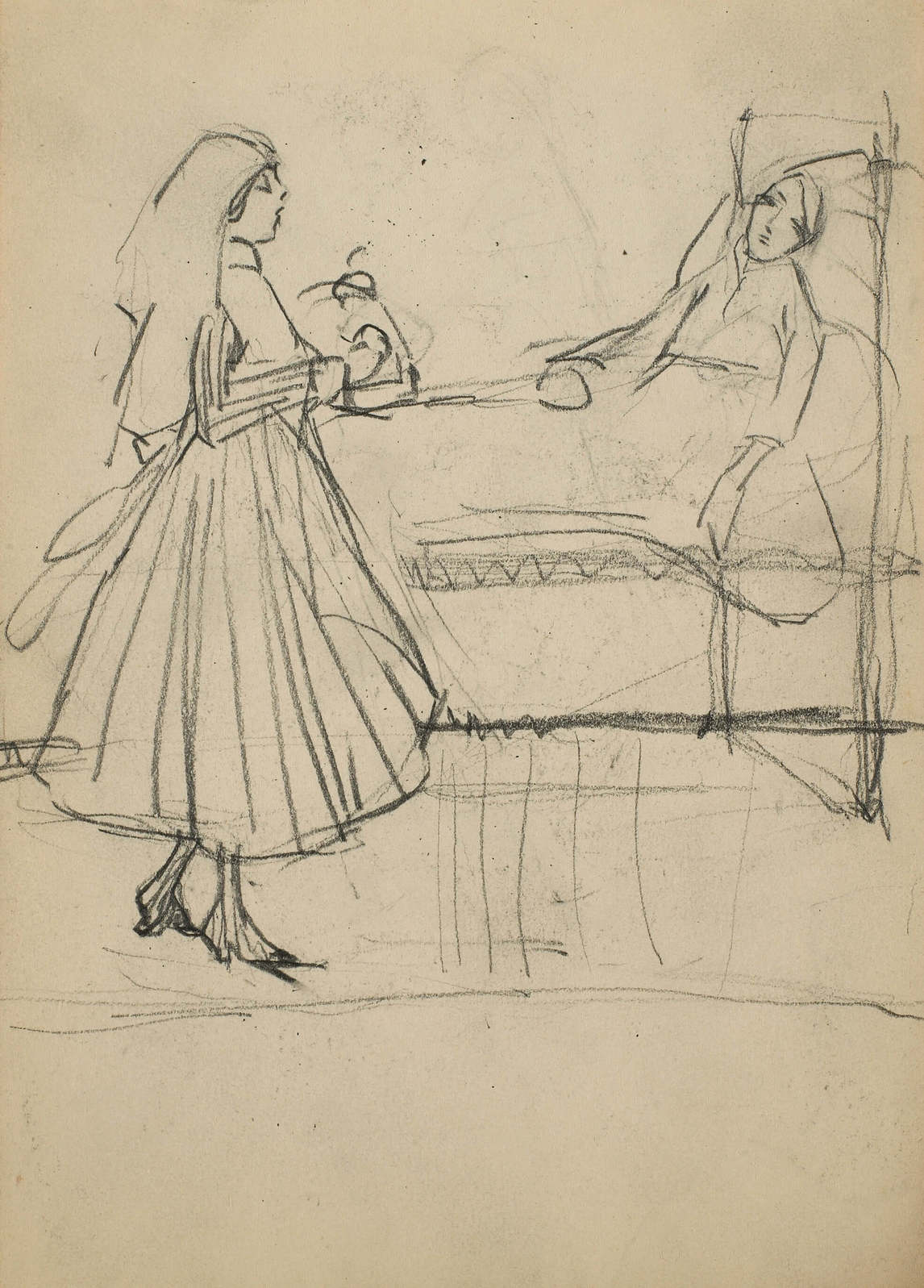

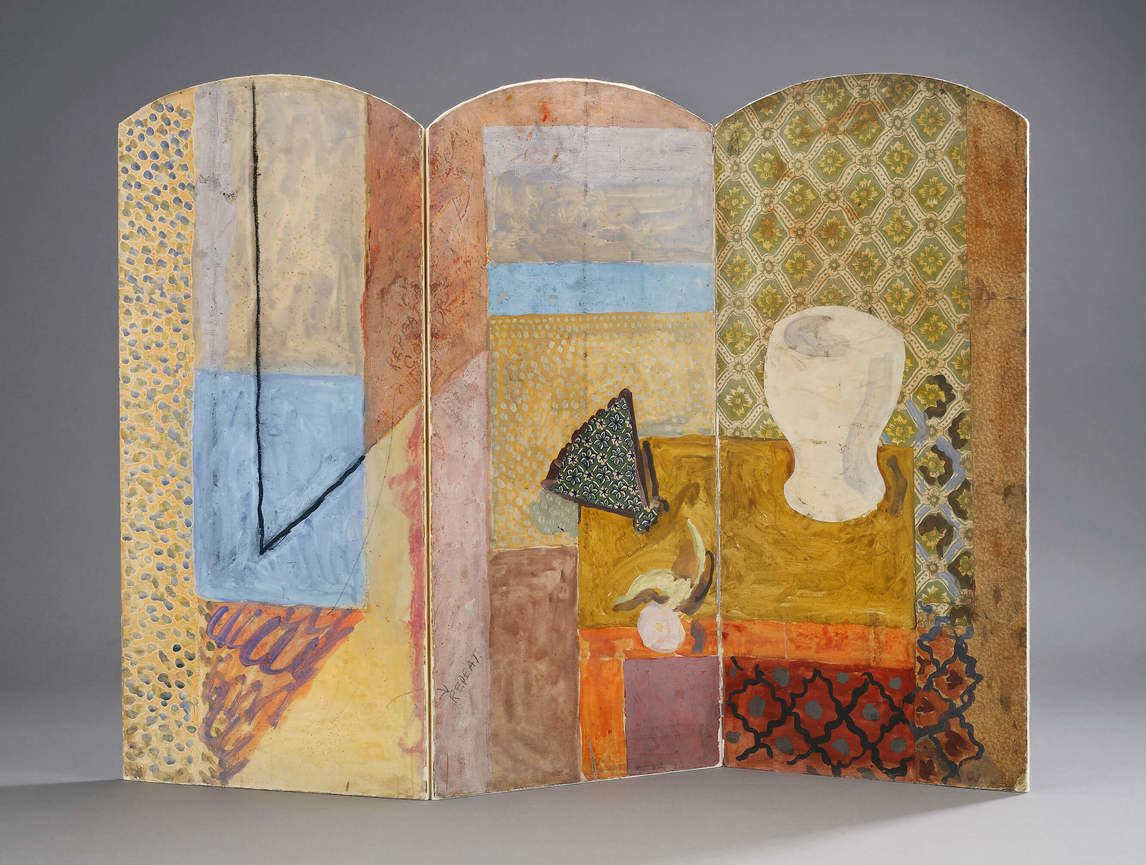

Heward, along with her mother and her sister Honor, followed not long after, working for the Red Cross in England. She recalled later that she had been “unable to continue her painting” during these years. Being in London, however, benefited her art, as Heward attended exhibitions and learned about European modernism, which she later drew on in her work. Her cousin was the well-known Montreal interior designer Mary Harvey, who, it is believed, introduced Heward to the decorative arts of Roger Fry’s Omega Workshops and to the work of English painter Vanessa Bell (1879–1961), a designer of screens, textiles, and mosaic floors. The Heward family returned to Montreal in 1919, when she was twenty-three.

Montreal Success and French Training

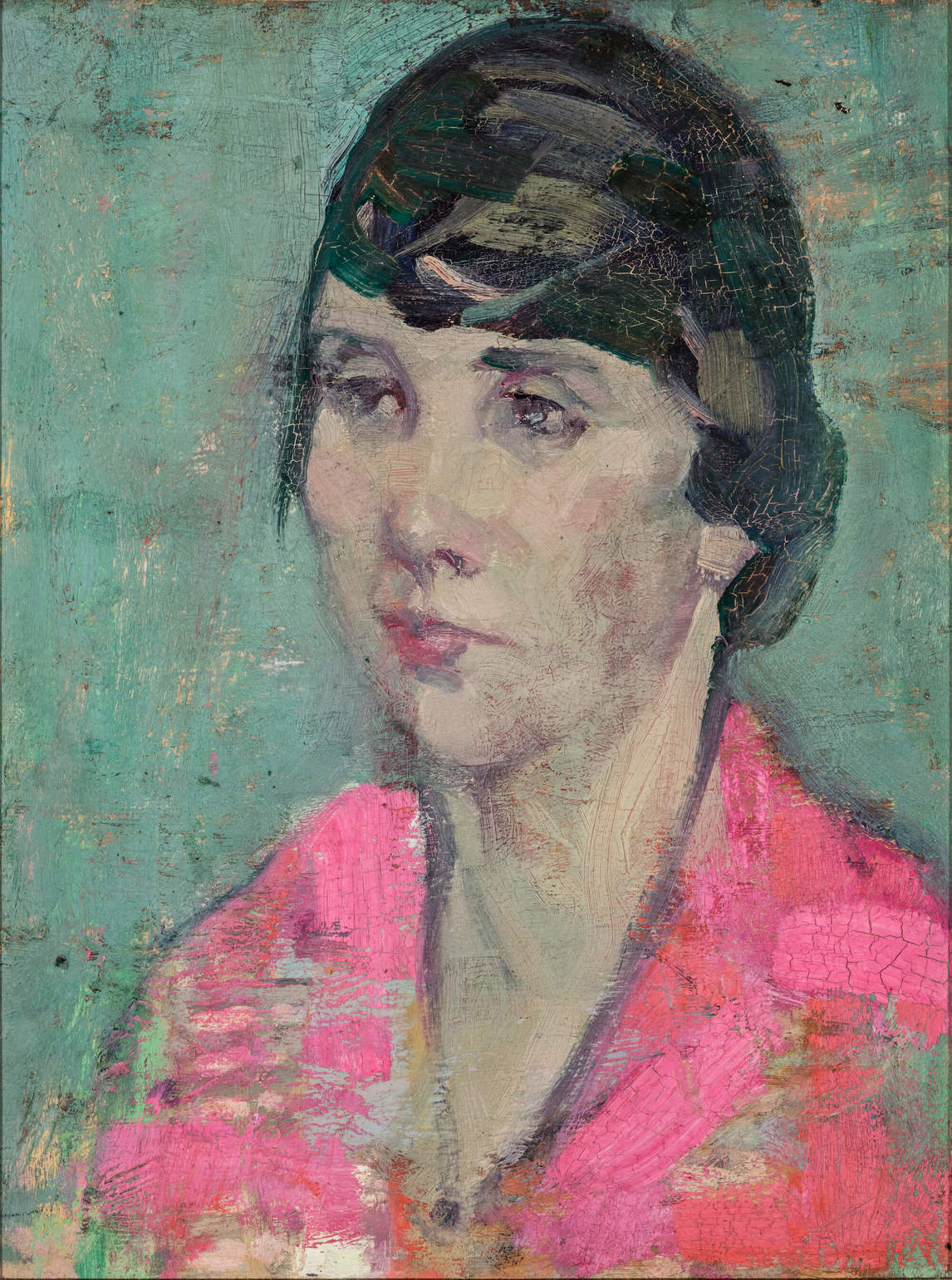

On her return from Europe in 1919, Heward enrolled at the Art Association of Montreal (AAM) and studied under William Brymner (1855–1925) and Randolph Hewton (1888–1960). There Heward met fellow artists Edwin Holgate (1892–1977), Lilias Torrance Newton (1896–1980), and Sarah Robertson (1891–1948), among others.

She was inspired by Brymner, who was influenced by the Impressionists and French modernists, including artists such as Paul Gauguin (1848–1903) and Henri Matisse (1869–1954). Brymner encouraged his students to engage with a range of subject matter, and urged them to develop their own approaches to colour use and representation of the human form. His openness to figure painting and advocacy of interpretative freedom influenced Heward and other Montreal artists who were focusing on painting figures at a time when the preferred Canadian subject matter was the landscape.

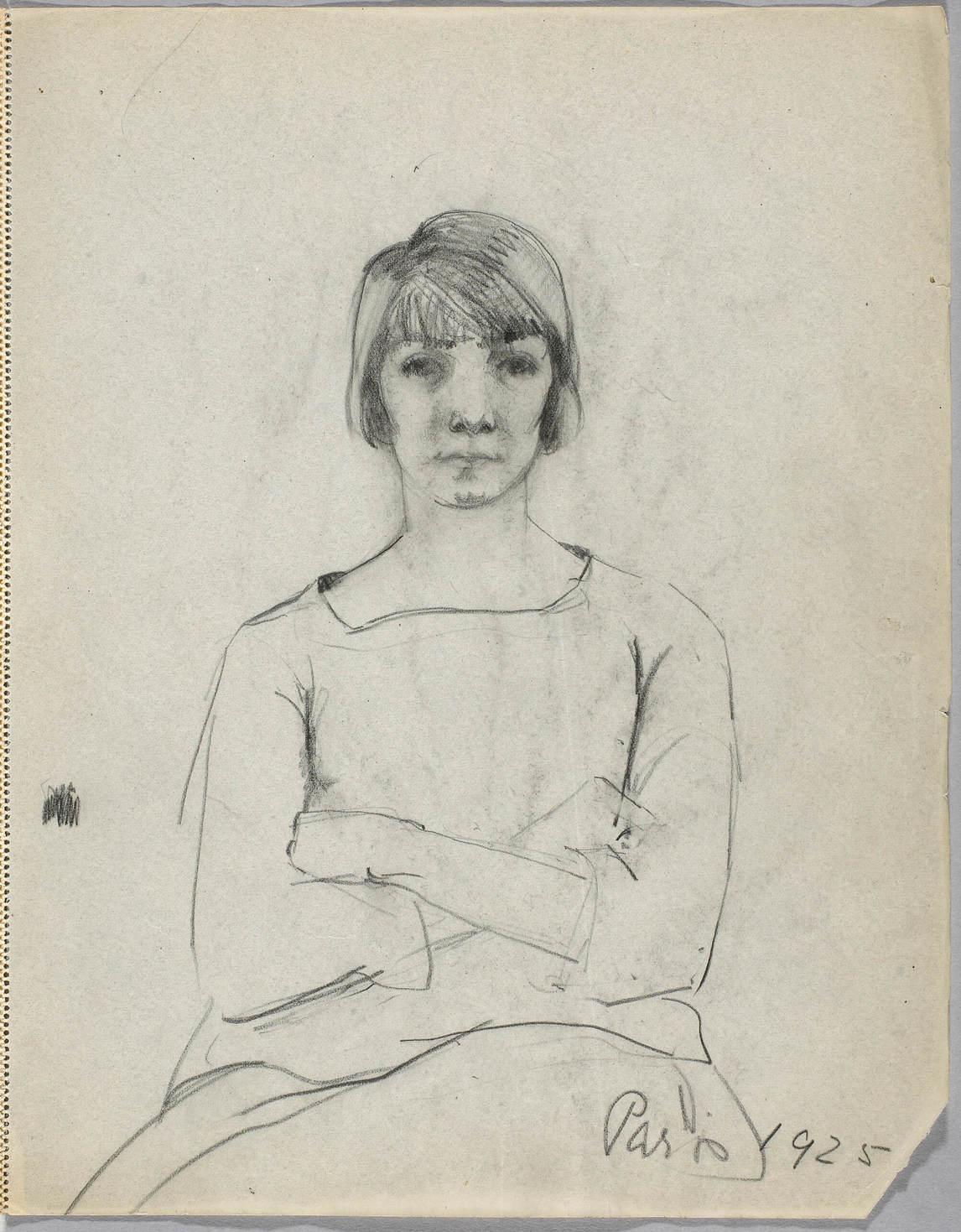

Heward began to have professional success as an artist in the early 1920s. She placed second in a competition for the Reford Prize for painting at the AAM in 1922, and as a student in the advanced class there, she won both the Reford Prize and the Women’s Art Society Prize for painting in 1924. Encouraged by her achievements, she travelled to London in 1925 for the first time since the end of the First World War, to study art.

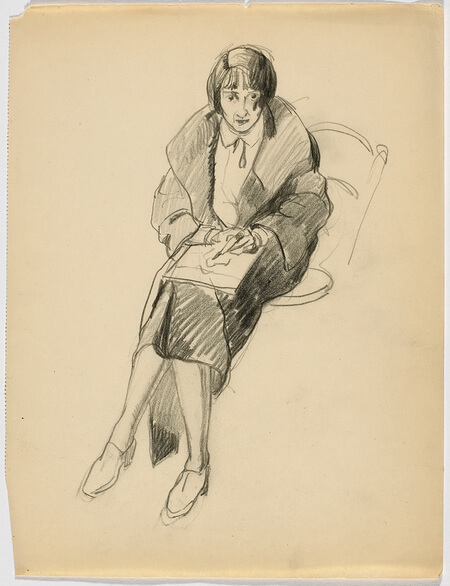

From London Heward moved to Paris and took classes at the Académie Colarossi, where she was taught by Charles Guérin (1875–1939), a French Post-Impressionist painter who had been a pupil of Gustave Moreau (1826–1898), one of Matisse’s teachers. She also studied drawing at the École des beaux-arts under Bernard Naudin (1876–1946). This training in France, though brief, influenced her art practice throughout her life and her ongoing search for a personal style with which to represent human subjects. As with many French modernists, particularly the Post-Impressionists and Fauves, she painted people and things as she “saw” them, not necessarily as they actually appeared.

Recognition and Praise

From early in her career, Heward garnered attention from the press with her paintings. She first received public acknowledgement in 1922 when she placed second in competition for the Reford Prize for painting at the Art Association of Montreal (AAM); her portrait Mrs. Hope Scott, c. 1922, had been included in that year’s Spring Exhibition. In 1924 when she was a student in AAM’s advanced class, she won both the Reford Prize and the Women’s Art Society Prize for painting. The next year the jury for the Canadian section of the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley, England, selected her portraits of Mabel Lockerby (1882–1976), painted around 1924, and Eleanor Reynolds, 1924. In 1925 an unidentified reviewer in the London Sunday Times singled out Heward’s Miss Lockerby, c. 1924, noting that it was “a very promising, simply painted head.”

In 1929 she won first prize at the Willingdon Arts Competition for Girl on a Hill, 1928, a work depicting the modern dancer Louise McLea. One critic, writing in February 1930, commented that Heward was on her way to Paris and therefore would not hear the positive chatter about paintings such as At the Theatre, 1928, and Rollande, 1929. A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974) noted her Willingdon painting in a letter to Isabel McLaughlin (1903–2002):

I went down to the opening [of the R.C.A. exhibition]. badly hung. and full of junk. Prudence Heward had a fine canvas there. I am sending her over to you as a little playmate. she leaves Jan 12th. I feel sure you will like her. though perhaps you are too much alike in character. like you she is reserved. and very modest about her work. and very generous in her appreciations of others. work. and very honest about what she likes and dislikes. and beneath all her quietness she has a nice little will of her own. You will remember she won the Willingdon prize. it was between her two canvases for first place. For a long time nobody took her very seriously. today. I think she and Holgate are the strongest painters in Montreal.

Heward never married. Although we don’t know her reasons, in early twentieth-century Canada, a woman who married was often discouraged from continuing to work, whether by her husband or by social norms related to expectations of women’s roles as wives and mothers. Heward is certainly not the only female artist in the early twentieth century to choose the unmarried life. The majority of women associated with the Beaver Hall Group did not wed.

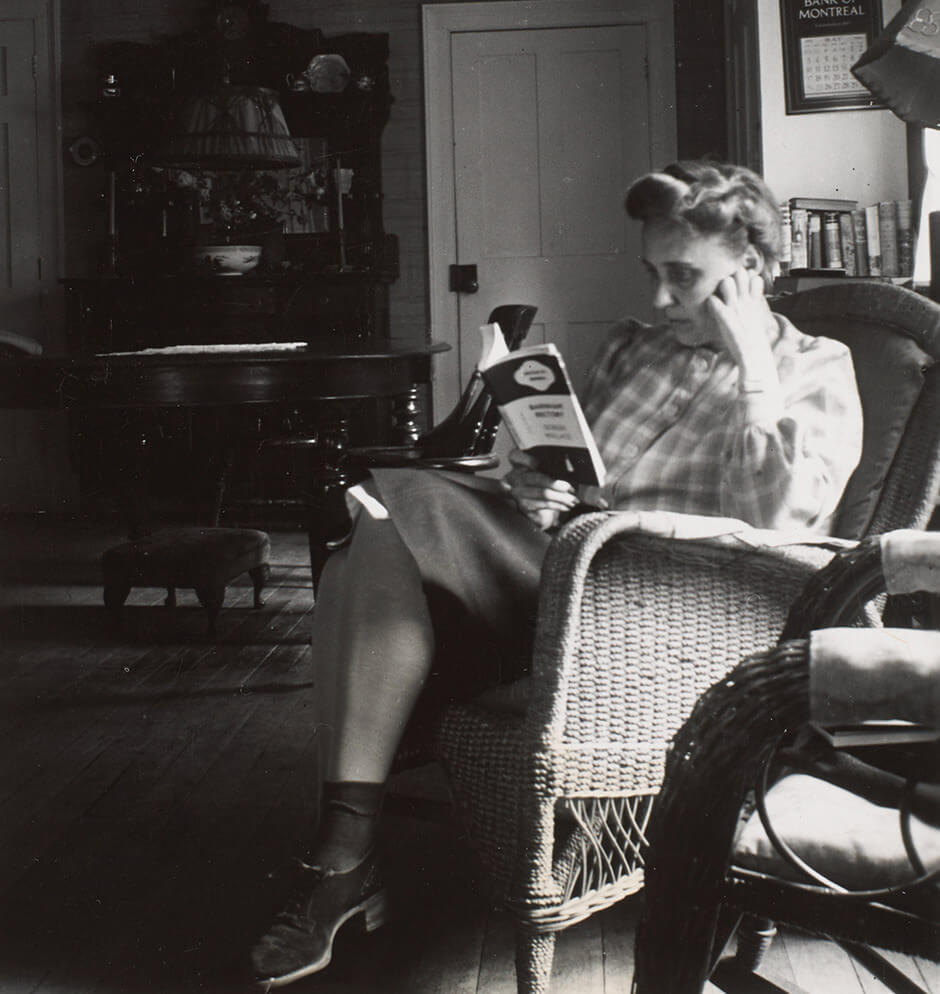

In 1930 Heward and her mother moved into a large house at 3467 Peel Street, where she had a studio on the top floor. They lived together until the artist’s death in 1947. Her life was full of intimate friendships, such as the one she shared with McLaughlin.

Friendship with Isabel McLaughlin

Through an introduction by A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974), Heward met Isabel McLaughlin (1903–2002), who was living in Paris and with whom she became lifelong friends. Both Heward and McLaughlin enrolled in classes at Paris’s Scandinavian Academy in 1930. According to Heward’s nephew, “When in Paris, Aunt Prue lived on the more conventional right bank and crossed over to the other side to study and paint. [André] Biéler felt that the Right Bank represented her more conventional well-to-do family background, while the Left Bank represented her artistic temperament.” From Paris, Heward and McLaughlin travelled to Italy, sketching in Florence and Venice. Heward produced several small oil sketches of Venetian scenes during this trip as well as during her previous trip to Europe, such as Venice, c. 1926. A Montreal Gazette critic referred to Heward’s “impressionistic sketch of Venice” in a review of her first solo exhibition in 1932.

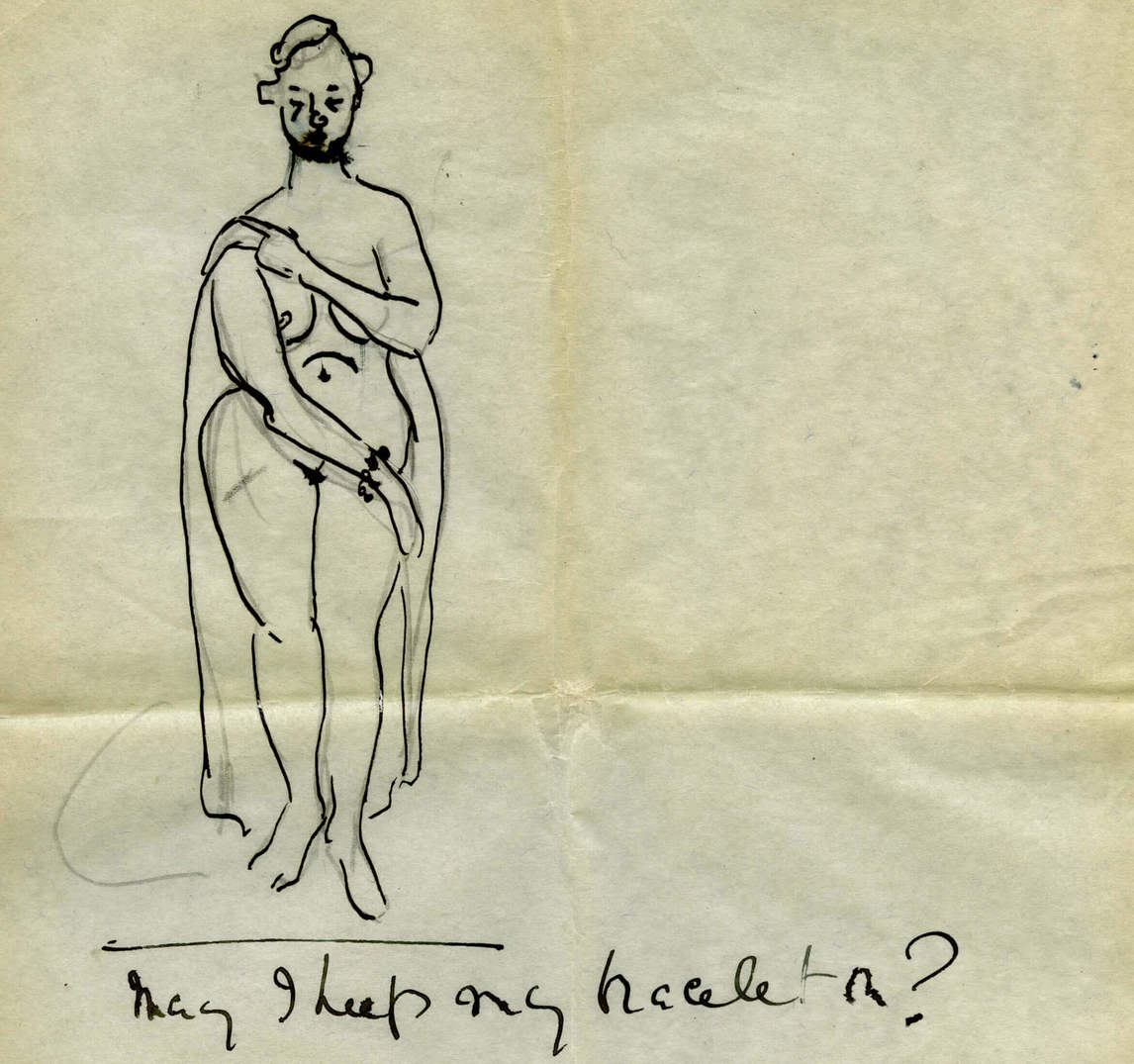

The many letters Heward wrote to McLaughlin are an important source of information about Heward’s interests, anxieties, and personality. They are often infused with humour and a sense of playfulness. In a letter from November 7, 1944, Heward describes how she had recently gone to see her doctor: “I was completely undressed and called out to him ‘Oh Doctor, is it alright if I keep on my bracelet?’” On a sheet of paper attached to the letter, Heward had sketched a self-portrait in which she is naked, her left arm held across her chest and her right arm partially covering her stomach. On her right wrist she wears the bracelet she alludes to in her note.

In 1936 Heward travelled to Bermuda to stay at the McLaughlin family home. Although Heward had completed at least one painting of a black woman before this trip (Dark Girl, 1935), during her stay she likely gained inspiration for several of her paintings of black women, such as Hester, 1937, and Girl in the Window, 1941. She sketched, and possibly painted, black women living in Bermuda, and upon her return home also painted black women in Montreal.

Work in the Thirties

Although Heward specialized in painting people, multiple times in the late 1920s and early 1930s she was invited to exhibit with the Group of Seven, who favoured landscape painting. In 1930 her works At the Theatre and The Emigrants, both painted in 1928, were part of the Group of Seven exhibition at the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario) and at the Art Association of Montreal. In 1931 three of her paintings—Girl Under a Tree, 1931, Cagnes, c. 1930, and Street in Cagnes, c. 1930—were included in another Group of Seven exhibition at the Art Gallery of Toronto.

By 1932, at the age of thirty-six, Heward was offered her first solo exhibition, at W. Scott & Sons Gallery in Montreal. In preparation, she wrote to Eric Brown, director of the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, asking, “May I have the two [Rollande, 1929, and Girl on a Hill, 1928] that are at the National Gallery? To have a ‘one man show’ I would need everything…. I must know for sure before I decide about my show, its [sic] going to be a devilish lot of work.” In the end Girl on a Hill was not included in her solo show, likely because it was already part of the 1932 exhibition Paintings by Contemporary Canadian Artists at New York’s Roerich Gallery. That exhibition ran from March 5 to April 5, so the painting would not have been available in time for Heward’s solo show, which opened in Montreal in mid- to late April.

Throughout the thirties, Heward was an active member of artists’ groups that were considered modern and avant-garde. She joined the executive committee of The Atelier: A School of Drawing Painting Sculpture in 1931, thereby supporting its founder, artist John Lyman (1886–1967). The Atelier was sympathetic to trends of European modernism, which resonated with Heward’s own artistic style. She was co-founder and vice-president of the Canadian Group of Painters (1933–39), and a founding member of the Contemporary Arts Society (1939–44). In 1941 she attended the Kingston Conference, organized by André Biéler and held at Queen’s University.

Contrary to popular belief, Heward was not an official member of Montreal’s Beaver Hall Group (1920–21), which itself had no official mandate or manifesto. But she was closely affiliated with the group, becoming friends with many of the members and exhibiting with them on several occasions. Unlike the artists who exhibited as part of the group, however, she did not need studio space at Beaver Hall Square, as she worked from the top floor of her mother’s large house at 3467 Peel Street, which she depicted in Study of the Drawing Room of the Artist, c. 1940.

Known for her integrity and solidarity, Heward, in 1933, was asked to join the selection committee, with Lawren Harris (1885–1970) and Will Ogilvie (1901–1989), for the Canadian Group of Painters exhibition at the Art Gallery of Toronto. When the gallery’s trustees worried that Nude in the Studio, 1933, by Lilias Torrance Newton (1896–1980), would be found offensive because of the nudity, Heward argued that the exhibition should be cancelled unless the work was included. Nude in the Studio was ultimately removed from the show. Despite her resistance, Heward was persuaded by her fellow artists to allow the exhibition to proceed as planned.

Illness and Injury

The asthma that plagued Heward throughout her life worsened after she was involved in a car accident in May 1939, when her friend Blue Haskell swerved his car on Peel Street and hit a tree. Heward’s nose was injured, and this exacerbated her already poor health. She was likely further weakened by the grief that followed her sister Honor’s suicide in 1943. Heward travelled to Los Angeles in 1947 with her mother and her sister Rooney to seek treatment at the Good Samaritan Hospital. She died in Los Angeles on March 19, 1947, at the age of fifty.

A memorial exhibition of her work was organized by the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, in 1948. A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974) wrote the catalogue essay, and Anne Savage (1896–1971) gave the address for the opening reception at the Montreal Museum of Fine Art on May 13, 1948. In that address, Savage remarked, “Not since the days of J.W. Morrice [1865–1924] has any native Montrealer brought such distinction to her native city, and never before has such a contribution been made by a woman.” The exhibition travelled to nine Canadian cities during its sixteen-month tour.

Rediscovery

Heward was one of the first Canadian women artists to be rediscovered in the 1970s and 1980s, when feminist art historians began organizing exhibitions and writing about women artists who had been well known and respected during their lifetimes but who had not yet received adequate scholarly attention. In 1975 art historians Dorothy Farr and Natalie Luckyj curated From Women’s Eyes: Women Painters in Canada at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre in Kingston, Ontario, and in 1986 Luckyj spearheaded Expressions of Will: The Art of Prudence Heward, also at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre. Thanks largely to these feminist exhibitions and accompanying catalogues, Heward is now recognized as an important modernist artist of the early twentieth century, and her paintings continue to garner attention from art historians concerned not only with Canadian art but also with issues of class, gender, and race.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements