At the Café (Miss Mabel Lockerby) c. 1929

Prudence Heward, At the Café (Miss Mabel Lockerby), c. 1929

Oil on canvas, 68.5 x 58.4 cm

Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

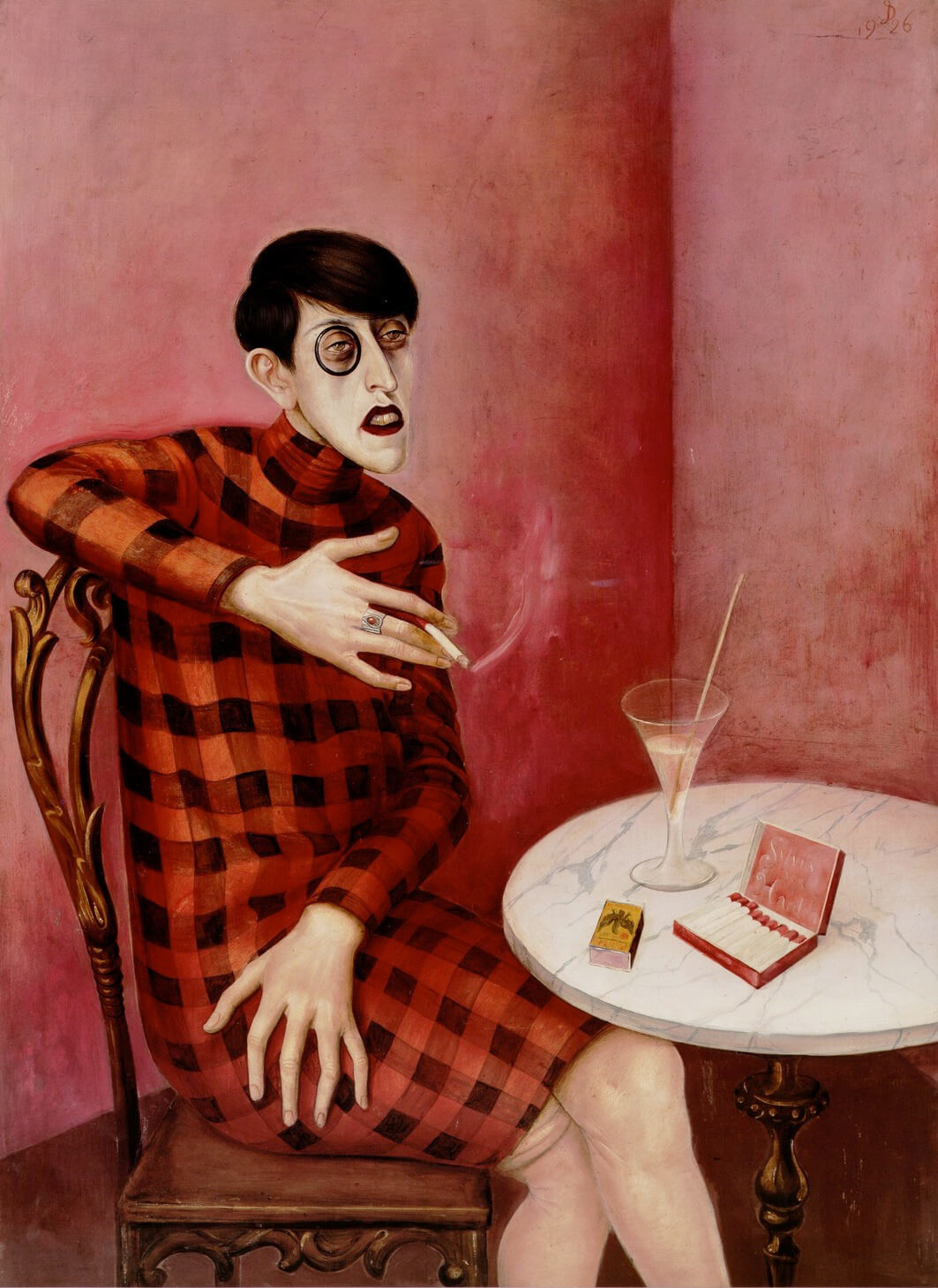

Heward’s At the Café represents a theme favoured by many European male artists in the 1920s: the solitary female seated in a coffee house. This subject spoke to women’s increased freedom and their desire to be alone in public spaces. In 1926 German artist Otto Dix (1891–1969), for instance, painted the journalist Sylvia von Harden seated in a café. Between her famously long fingers the sitter holds a cigarette, a signifier of female emancipation in Europe and North America at that time. Von Harden’s red-and-black checkered dress clashes with the acid-pink background, a pink similar to that of the apron worn by the young woman in Heward’s 1929 painting Rollande.

The woman portrayed in Heward’s At the Café is artist Mabel Lockerby (1882–1976), whom Heward knew well from the Montreal art scene and the Beaver Hall Group’s exhibitions and social activities. Lockerby wears a vibrant red smock-like jacket over a navy-blue blouse. She shares the severe expression seen in many of Heward’s portraits, as well as the rosy complexion of the women in Girl on a Hill, 1928 and Rollande, 1929. This is not a naive, inexperienced artist. She is self-contained and possibly world-weary.

Remarkably for Heward’s oeuvre, shadowy figures appear in the background. Their dark coats and fedoras suggest that these figures are men; however, Heward may have intended them to be read as cross-dressing women. The queer English artist Gluck (1895–1978; born Hannah Gluckstein into a wealthy Jewish family) was often photographed in hats and coats very similar to those worn by the figures in this painting’s background. Reading these two figures as androgynous women supports a queer and feminist interpretation of At the Café as a work that speaks to women’s increased presence in public places traditionally regarded as masculine.

At the Café is arguably Heward’s most modernist painting: not only does it employ Art Deco design vocabulary but it also represents a female artist, alone, in a public space, and it points to the possibilities of queer spectatorship. Significantly the obscenity trial against Radclyffe Hall’s classic lesbian novel The Well of Loneliness had occurred in England in 1928. It was as a result of this trial that certain visual signs—for example, the cigarette, the monocle, and androgynous or masculine dress—had begun to be interpreted as signifying lesbian identity.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements