Prudence Heward was one of the most innovative artists working in Canada during her lifetime. Most of her artistic training took place at the Art Association of Montreal under the guidance of her teacher William Brymner (1855–1925), who was influenced by various schools of French modernism. Heward thus was aware of European movements and techniques—the consistent use of intense coloration, strong compositional planes, and sculptural treatment—and this in turn influenced her painting style.

Figure Painting and the Nude

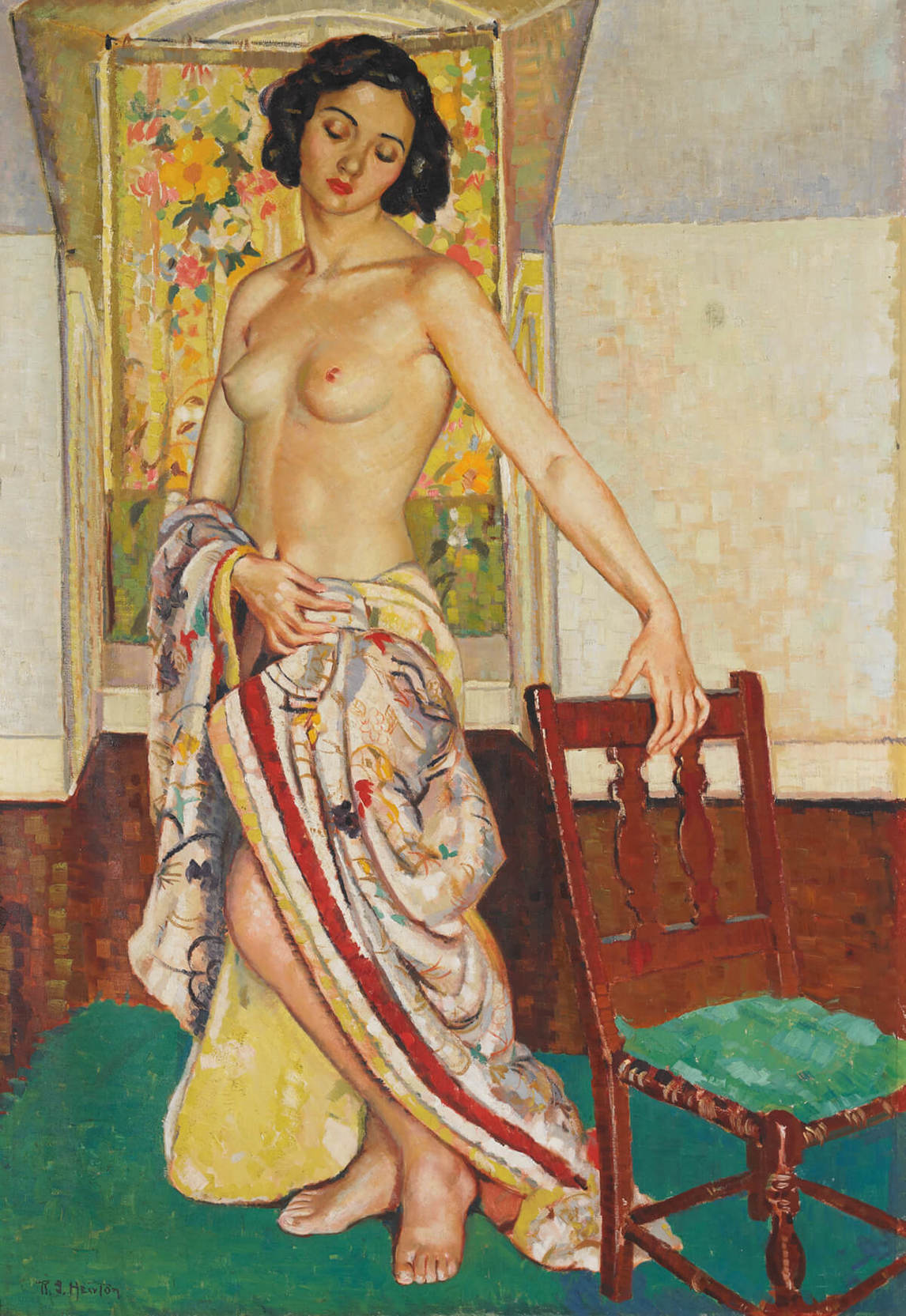

In the early 1930s Montreal artists such as Edwin Holgate (1892–1977) and Lilias Torrance Newton (1896–1980) were particularly interested in representing the human form. Heward too, although she also painted landscapes and still lifes, was primarily a painter of human subjects. She preferred the term “figures” to portraits, and most of her figurative paintings represent women. She painted mostly white women, but she also produced several works that represent black female subjects in various states of undress, as well as a few paintings portraying indigenous girls. Girl Under a Tree, 1931, is one of her very rare depictions of a white female nude.

The female nude was a major subject for nineteenth-century European artists. The 1863 painting Olympia by Édouard Manet (1832–1883) is part of a long lineage of white female nudes, but it caused a scandal because of the subject’s direct gaze, which positioned the viewer as her next client—Olympia was a popular name for prostitutes in the nineteenth century. The subject is shown wearing fashionable shoes and jewellery, thereby highlighting that she is a “real” woman who has undressed, not a mythical nude such as Venus, who is “naturally” without clothes. Like Manet’s Olympia, Heward’s women often return the viewer’s gaze, and they are realistically rendered rather than unrealistically idealized.

Heward studied at the Art Association of Montreal under William Brymner (1855–1925) and Randolph Hewton (1888–1960). Brymner had trained under William Bouguereau (1825–1905) in France, and he was influenced by French modernists such as Henri Matisse (1869–1954) and Manet, who prioritized figure painting, including but not limited to the female nude. He encouraged his students—Heward, Sarah Robertson (1891–1948), Edwin Holgate, and Anne Savage (1896–1971) among them—to not simply copy nature but to develop their own individualistic style and to communicate emotion through their art. Brymner was receptive to a broad range of subjects beyond landscape, which suggests that in having him as a teacher, Heward would have felt supported in her desire to focus on representations of female subjects.

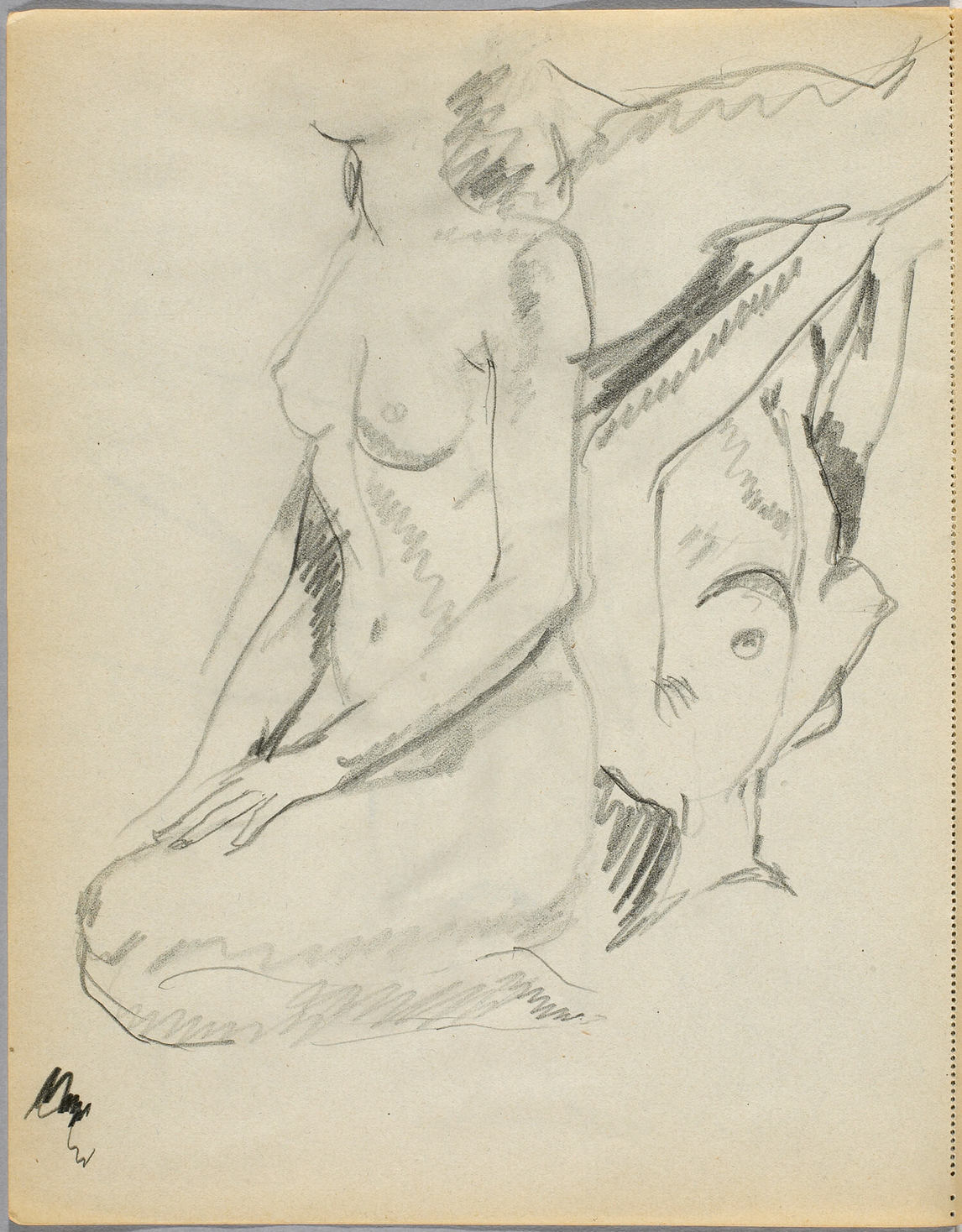

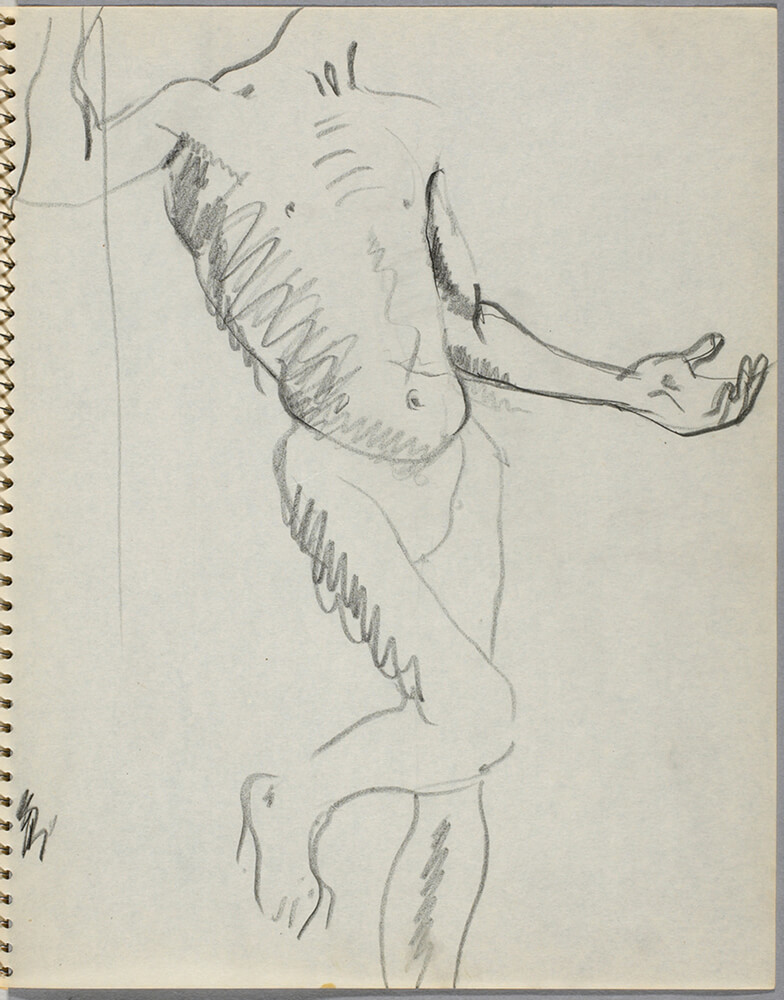

Heward produced the majority of her paintings in her studio in the house she shared with her mother on Peel Street in Montreal. Heward’s nephew has noted her vigorous approach to painting: “As far as I can remember she always painted standing up, blocking out broad strokes of charcoal on her canvases.” According to curator and art historian Janet Braide, Heward’s pencil studies indicate that she produced quick study sketches on paper, then oil on panels (usually 12 x 14 inches), and, finally, her finished work in oil on canvas.

Landscapes and Still Lifes

In addition to her well-known portraits of women and children, Heward produced many landscapes and still lifes throughout her career. She painted landscapes in Montreal, such as the early work McGill Grounds—Winter, c. 1924; around Fernbank (Athens, Brockville), where her family had a cottage; in areas of rural Quebec (Knowlton, Laurentians, Eastern Townships); and in Venice, Cagnes, and Bermuda, where she visited her friend, Canadian artist Isabel McLaughlin (1903–2002) in 1936. She often painted en plein air on wood panels, and she went on many sketching trips with fellow artists, including A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974), Anne Savage (1896–1971), and Sarah Robertson (1891–1948). Occasionally Heward would “work up” one of her landscape paintings to serve as the background in her figure paintings; examples include Barbara, 1933, where the subject is depicted in front of foliage, and Dark Girl, 1935, which incorporates Heward’s study of Canadian sumach.

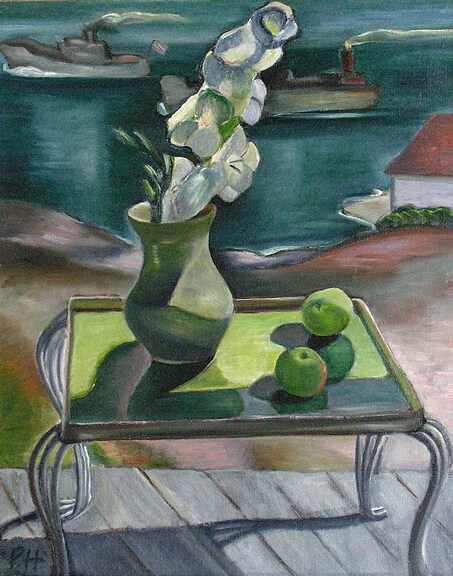

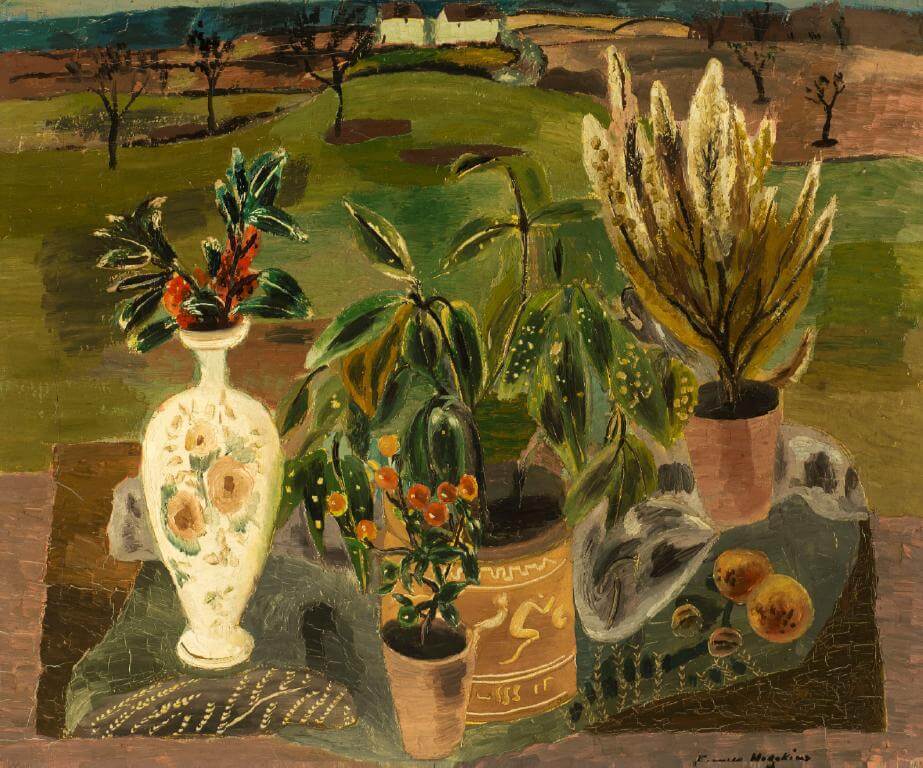

Still lifes, usually of fruit and plants, also feature in Heward’s oeuvre. She greatly admired the work of Frances Hodgkins (1869–1947), a New Zealand modernist who lived in England. Heward owned two still lifes by Hodgkins, and their influence can be seen in her painting A Summer Day, 1944, which depicts a vase of flowers and three green apples arranged on a small table in an outdoor setting. This unusual pairing of a still life against a background landscape is one Hodgkins also employed. Heward’s landscapes and still lifes of the 1930s and 1940s, like her portraits, are characterized by increasingly luminous colours and more expressive brushwork, showing her increased comfort with finding an individual style and subjective interpretation of nature.

Influence of Post-Impressionism

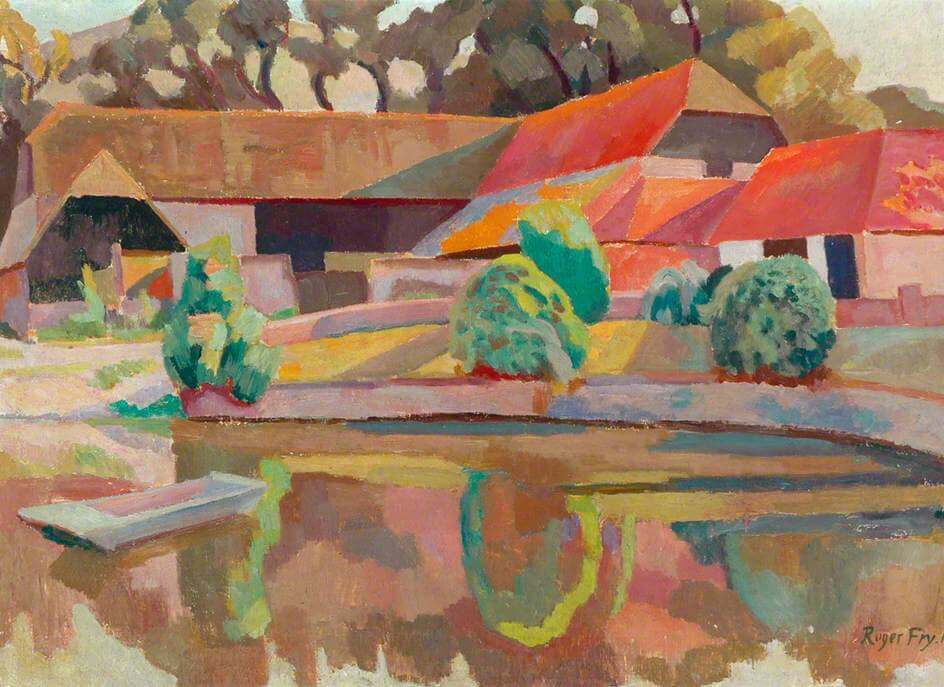

Heward worked for the Red Cross in London during the First World War, and while there she had access to exhibitions of work by modern artists—for example, artists associated with English art critic Roger Fry and the Omega Workshops, a collective of artists brought together by Fry in 1913 to design everyday objects using the innovative aesthetics of Post-Impressionism. Among the many exhibitions that would have been on display while Heward was in London were the Whitechapel Gallery’s Twentieth Century Art—A Review of Modern Movements (March 1914), and Paintings and Drawings of the War by Vorticist C.R.W. Nevinson (1889–1946) at the Leicester Galleries in October of 1916. When she died in 1947, Heward had a number of books on modern art in her collection, including Roger Fry’s Transformations (1926) and Living Painters: Duncan Grant (1930). Art historian Natalie Luckyj has observed that Fry’s writings on colour design appear to have greatly influenced Heward’s engagement with bold colours. Fry encouraged artists to give “the same persistent and prolonged study [to] the principles of colour design which have been devoted to … drawing light and shade.” He championed Post-Impressionist painters for their innovative colour explorations.

In paintings such as Rosaire, 1935, and Portrait (Mrs. Zimmerman), 1943, Heward employs expressive colour—bold, even shimmering, greens and yellows—that recalls the work of Post-Impressionists such as Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) and Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), who believed in the emotional potential of intense colour contrasts, an idea also adhered to by Fauve artists such as Henri Matisse (1869–1954).

Like Post-Impressionists, Fauves, and German Expressionists such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880–1938), Heward employed shocking and unexpectedly acidic colours in some of her paintings; for example, the pink apron in her 1929 work Rollande contrasts sharply with the rural background, enhancing the sense that Rollande is both physically and emotionally separate from the farmhouse in the distance. This work is consistent with Heward’s other large early works, which often employ a colour palette of pink, green, lavender, blue, and brown.

Influence of Art Deco

Works such as Rollande, 1929, and At the Café, c. 1929, display the influence of Art Deco, a decorative style first exhibited in Paris in 1925, the year Heward first travelled to that city. Art Deco is characterized by stylized images of women employing simplified figurative compositions, hard lines, and solid blocks of colour. Heward’s tight brushwork in her paintings of the late 1920s points to her interest in the Art Deco style, and her representations of strong, stylized women are reminiscent of works by the Art Deco artist Tamara de Lempicka (1898–1980). De Lempicka’s Portrait of the Duchess de la Salle, 1925, was exhibited in Paris in 1926. Heward’s bedroom on Peel Street, “with its silver painted bed, black lacquer chest of drawers, glass sconces, painted screen mirrors and sophisticated colour scheme of gray, pale chartreuse and accents of red,” was also decorated in the Art Deco style.

While in Paris, Heward studied at the Académie Colarossi, where she was taught painting by former Fauve artist Charles Guérin (1875–1939), who had been a pupil of the Symbolist artist Gustave Moreau (1826–1898). According to curator and art historian Charles C. Hill, her “trip to France resulted in a severe hardening of her style, especially noticeable in Sisters of Rural Quebec [1930] and Girl Under a Tree (1931).” He describes the style as “almost sculptural” in that her figures are highly modelled. Critics who reviewed Heward’s work during her lifetime also noted the sculptural depiction of her subjects.

A Style of Her Own

Ultimately Heward’s style was largely personal. In a review of her first solo exhibition in 1932, Group of Seven painter A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974) wrote: “Whether one styles her work as modern or not is of little moment—it is characterized by draughtsmanship of a higher order, with spaces generously filled. In some cases I would find the modelling of figures too insistent—one becomes too conscious of the artist’s understanding of planes and would feel happier if more was left to the imagination.”

This aspect of Heward’s style has met with criticism in discussions of Girl Under a Tree, 1931, in particular. Hill pointed to this painting for its “disturbing contradictions of style.” Artist John Lyman (1886–1967) noted in his journal that Heward is “numb to the lack of consistent fundamental organization—relations and rhythms…. [It is] disconcerting to find with extreme analytical modulation of figures, [an] unmodulated and cloisonné treatment of [the] background without interrelation. Bouguereau nude against Cézanne background.” In his comments, Lyman is referring to the contrast of the woman’s body, which is carefully modelled and highly finished—the protruding ribs and pelvic bones giving her a flesh-and-blood appearance—to the buildings in the background, which appear flat and stylized.

Heward continued to be influenced by schools of European modernism throughout her life. Anne Savage (1896–1971), in her address at the Montreal opening of Heward’s memorial exhibition in 1948, observed: “She understood all the various aspects of French painting—she delighted in it and appreciated it—Cézanne, Matisse, Picasso—but she didn’t come back a Matisse or a Picasso—she came back Prudence Heward.” Heward’s application of European principles and styles was not solely a formal concern; they also provided her with a dynamic visual vocabulary for depicting modern Canadian women in both rural and urban contexts.

Painter of Modern Canadian Women

Heward was concerned with pictorial unity and modernist approaches to line, form, and colour in her paintings, whether they were landscapes, still lifes, or portraits. She was also interested in representing women who did not necessarily fit feminine ideals of beauty in early twentieth-century Canada. The Bather, 1930, for instance, portrays a robust woman in a bathing costume; contemporary critics reacted with hostility to this work, perhaps in part because of the woman’s body type and unflattering pose.

In all of Heward’s representations of women produced between 1924 and 1945, when she stopped painting because of illness, the female subjects—rural or urban, black or white—are united through their lack of desire to please the viewer by smiling or performing expected roles. They often return the viewer’s gaze defiantly, cross their arms over their bodies, or hunch their shoulders. Heward’s paintings of modern Canadian women push against ideals related to femininity, making these works not only modernist but feminist as well.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements