In the first half of the twentieth century Ozias Leduc (1864–1955) was one of Quebec’s most important painters. He was born three years before the signing of the British North America Act and died just as the signs of the Quiet Revolution were beginning to appear. Yet he was not a transitional figure; instead, he embodied continuity. The changes that appear in his work reflect the sociocultural transformations that marked his lifelong focus on the centrality of art. For Leduc, the purpose of art was to manifest humanity’s highest values, and these were expressed through beauty. His legacy is defined by an artistic ideal centred on research and study: to achieve a greater knowledge of the self. Leduc profoundly affected Canadian art, not only through the work he created but also through the lasting impression he left on his students.

A Self-Taught Artist

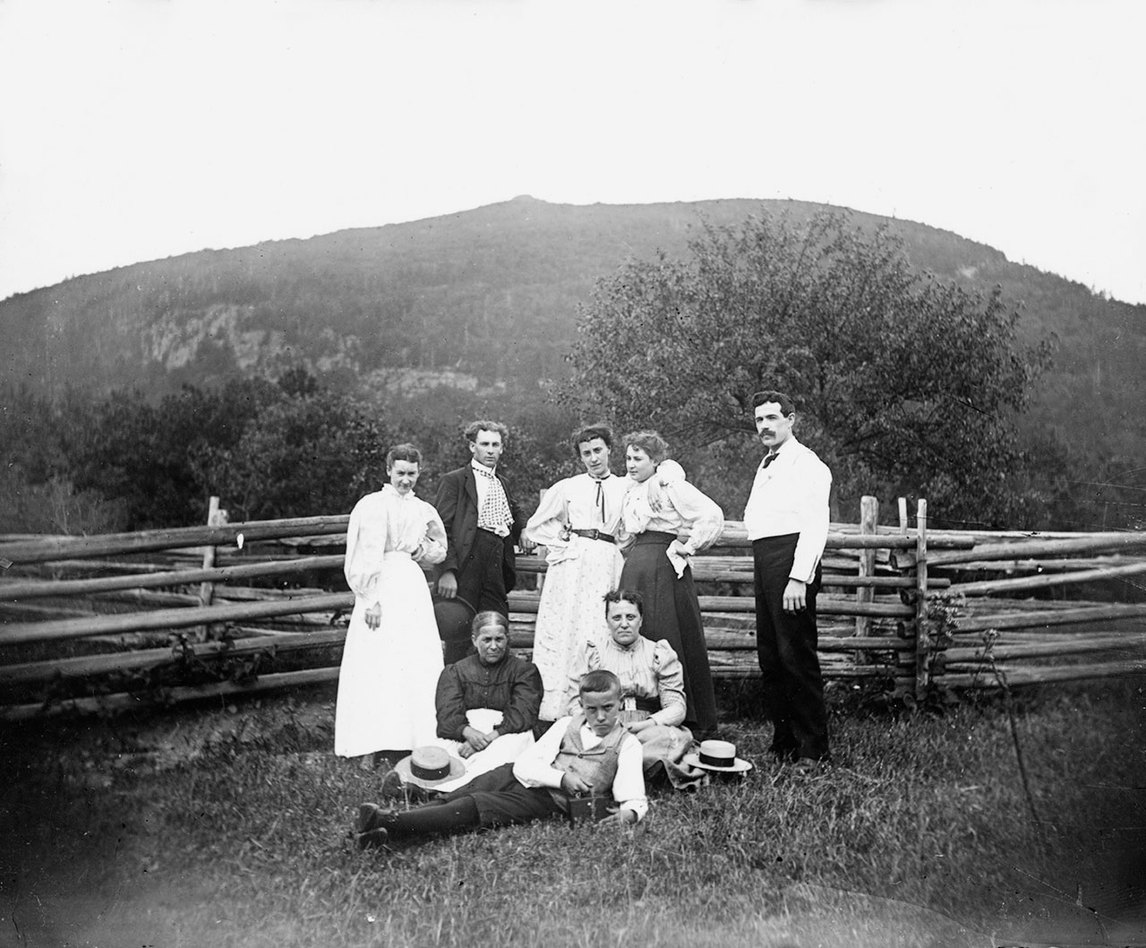

No one, at the beginning of Leduc’s life, could have predicted that he would become one of the most important artists of his generation. He was born in Saint-Hilaire, Quebec, on October 8, 1864, to Émilie Brouillette and Antoine Leduc, a carpenter, cabinetmaker, and farmer. Of this marriage, which took place in 1861, ten children were born, though only six survived into adulthood. Ozias was the second oldest. The Leduc siblings seem to have had a strong bond; Ozias was very close to his sisters Délia (Adélia) and Ozéma, and to his brothers Origène, Honorius, and Ulric. Ozéma and Honorius both served as his models in early drawings and paintings, and Honorius also acted as one of his artist assistants.

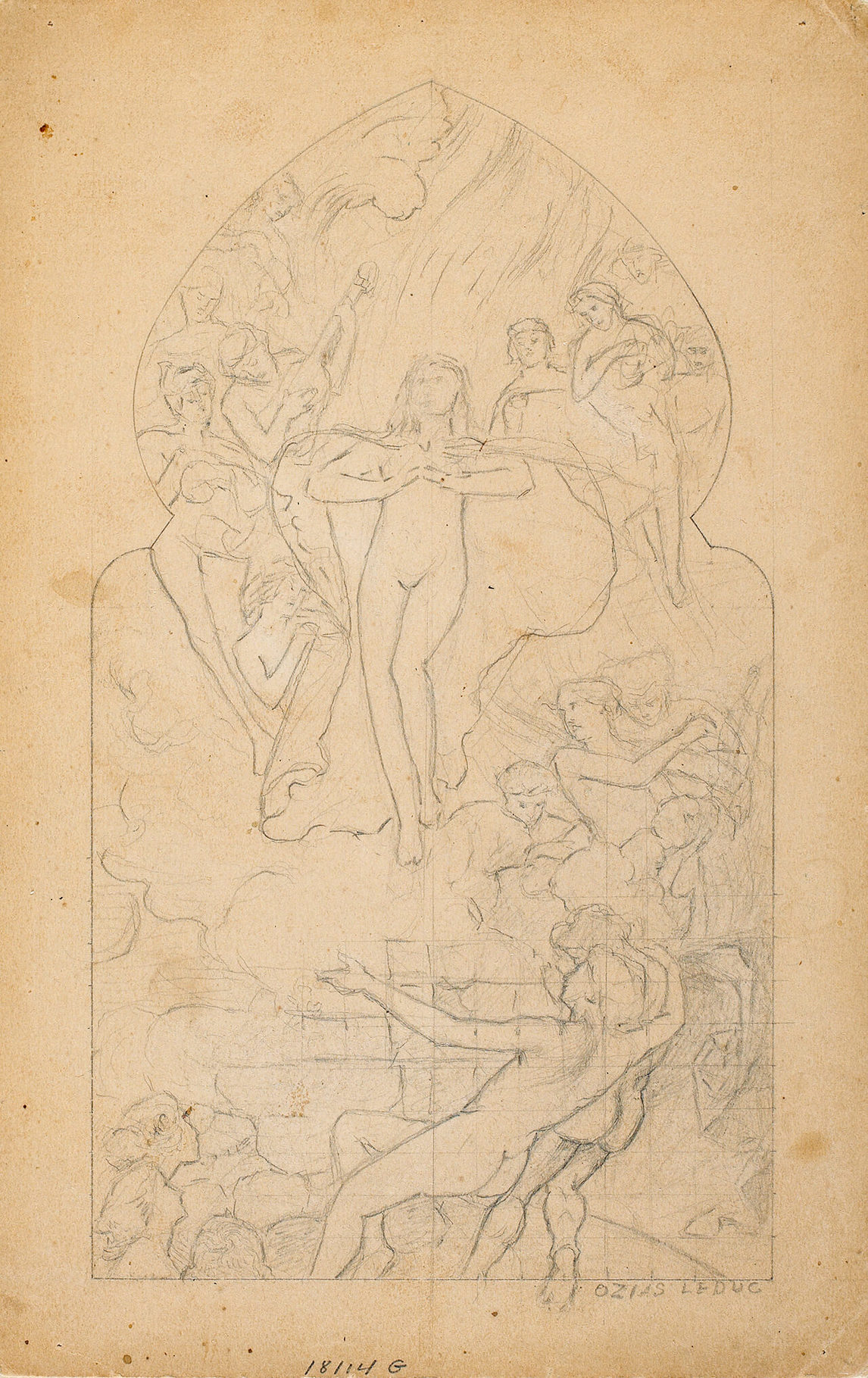

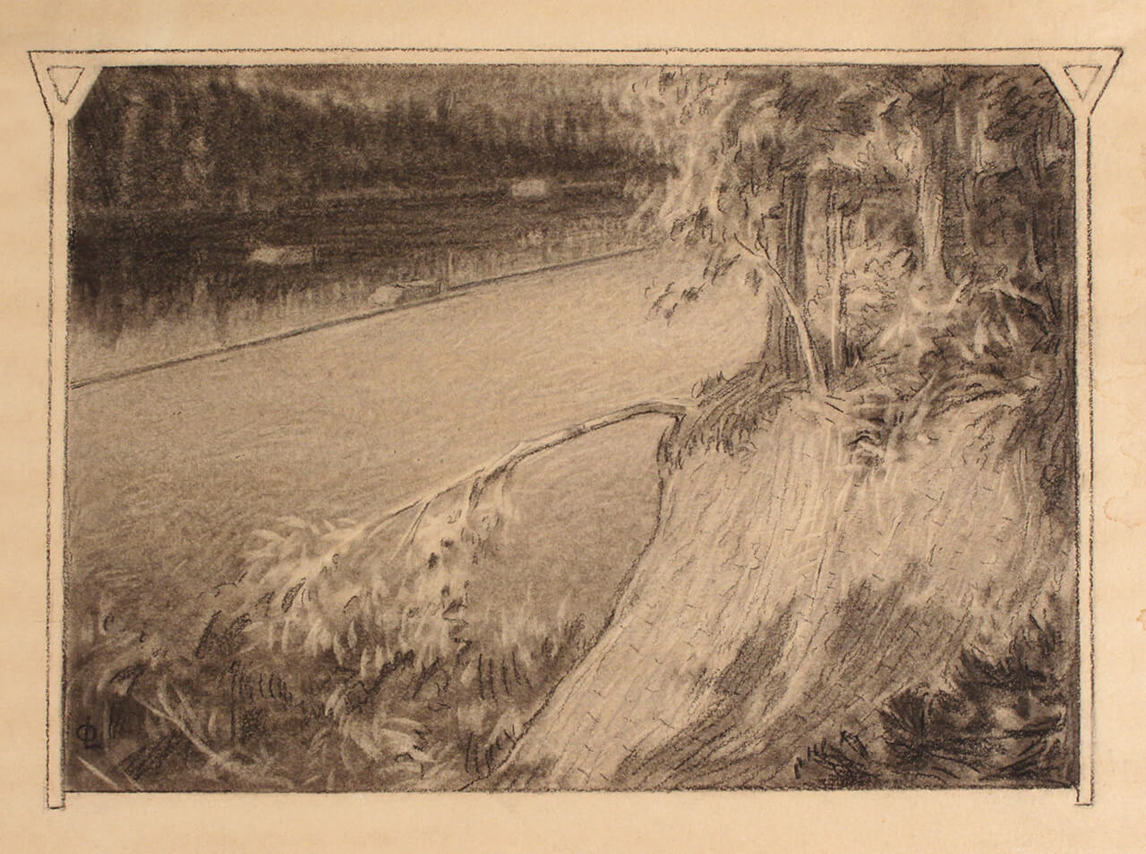

Saint-Hilaire, now the city of Mont-Saint-Hilaire, was then a village, located thirty-five kilometres northeast of Montreal. The family lived on the rang des Trente in a small house situated just under two kilometres from the Richelieu River, right at the foot of Mont Saint-Hilaire, as depicted in Lake View, Mont Saint-Hilaire (Vue du lac, mont Saint-Hilaire), 1937. The Leduc family owned a vast sloping tract of land that extended out from the mountain. One of nine hills in the Montérégie region, Mont Saint-Hilaire rises 410 metres above the Richelieu Valley. Its rugged topography, with caves, a quarry, and a lake, in addition to its wealth of minerals and diverse flora and fauna, fascinated Leduc, becoming both an object of study and the source of his imagination. The Richelieu River, an offshoot of the Saint Lawrence, opposes the mountain’s vertical landscape. Although the river seems to play a less important role in Leduc’s oeuvre, its flowing and undulating lines, suggestive of the Art Nouveau style, can be seen in many of his works, conveying a movement that unites all natural shapes. These meandering lines can be found in the curves of the snow in Gilded Snow (Neige dorée), 1916, for example, and in the rippling shapes that surround the figures in Mary Hailed as Co-Redeemer (L’Annonce de Marie co-rédemptrice), c.1922–32. An intimate and personal connection with nature was fundamental to Leduc’s philosophy, and Saint-Hilaire was the centre of a universe he would never cease to explore.

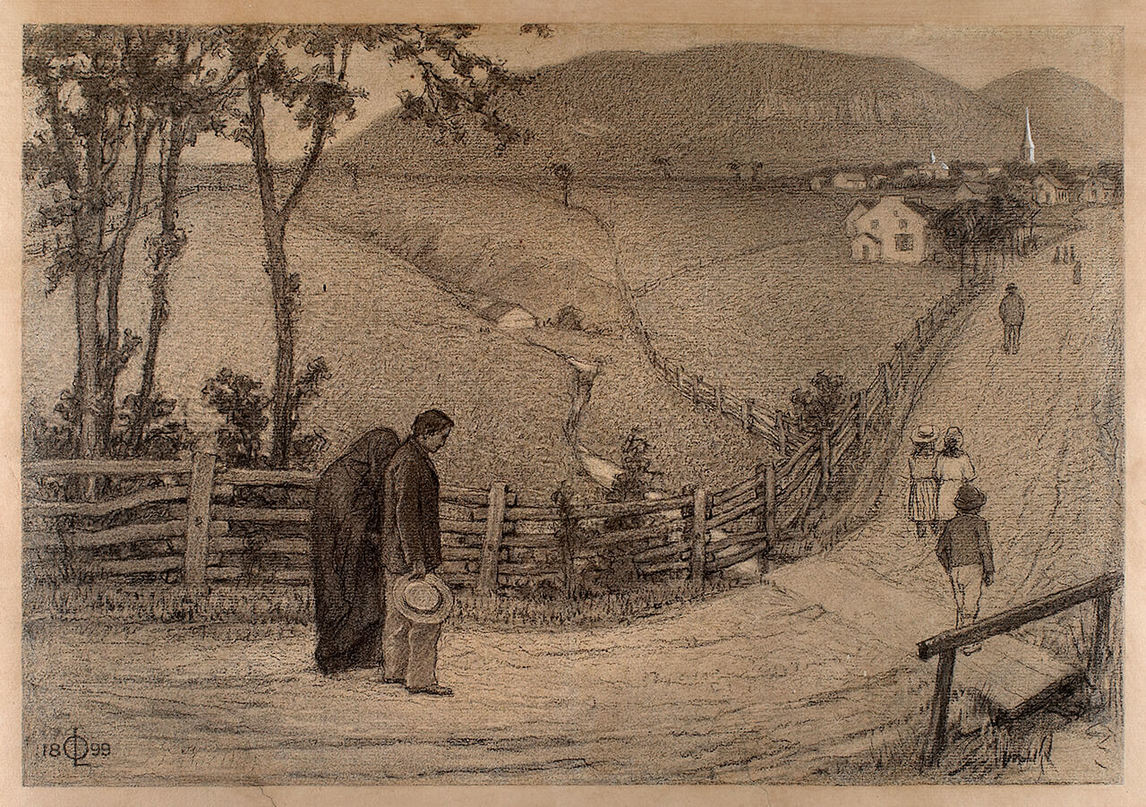

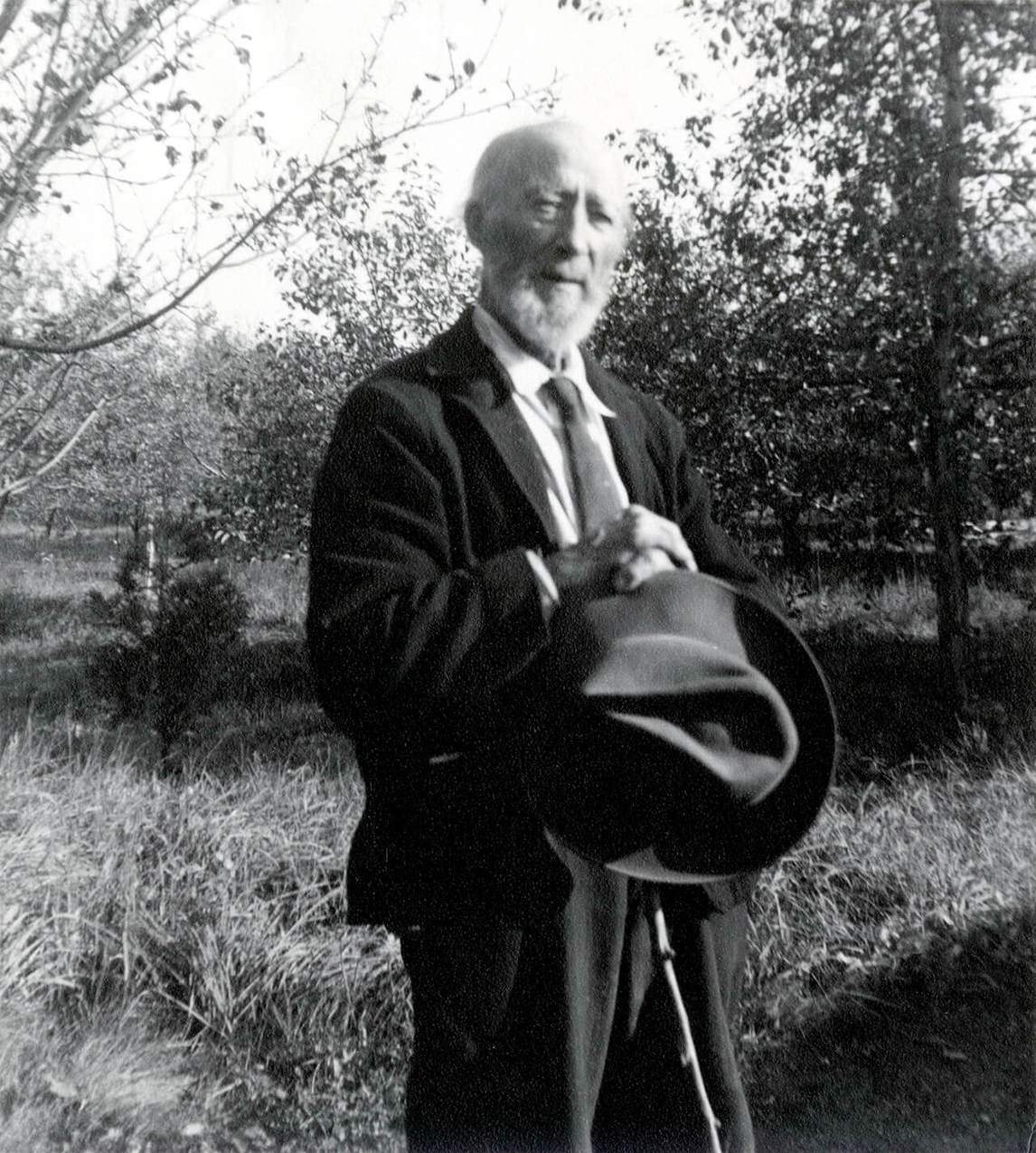

In contrast to the immeasurable landscape that surrounded him, Leduc was physically slight and short in stature. As a mature adult in the 1890s, he kept a beard and wore a hat to cover his increasing baldness. Both characteristics mark his appearance in his self-portrait of 1899. Photographs show him always well dressed, in a suit, white shirt, and tie; however, there is no archival evidence to suggest that he painted in this costume.

Many of his friends bore witness to the force of his personality. In 1954, Louis-J. Barcelo, a collector and friend of Leduc, would comment: “I was struck most of all by the beauty of his gaze, which was very gentle, as if lost in a dream, yet still luminous and penetrating, observing his interlocutor with interest and curiosity, and sometimes a gleam of amused malice. [. . .] this dreamer was above all a professional and a man of his craft, an honest, disciplined artisan.”

Although Leduc described himself as self-taught, his upbringing was not lacking in learning opportunities. His family instilled in him good habits and the perseverance to succeed. The manual labour that his father performed and the regularity that the upkeep of the family orchard demanded no doubt provided Leduc with a grounding in meticulous, regulated, and constant work. Throughout his long life he maintained a sustained studio practice that involved study, drawing, and painting.

From the beginning, Leduc was fascinated by books and in reading. In 1880, after completing his sixth year in the country schoolhouse on the rang des Trente, he entered the village “model” school. There, Jean-Baptiste-Nectaire Galipeau, who taught at the school for twenty-five years and also directed the local brass band, lavished him with praise. Leduc became very attached to him, and Galipeau in turn encouraged his young student’s training in the art of drawing, providing images as models to copy.

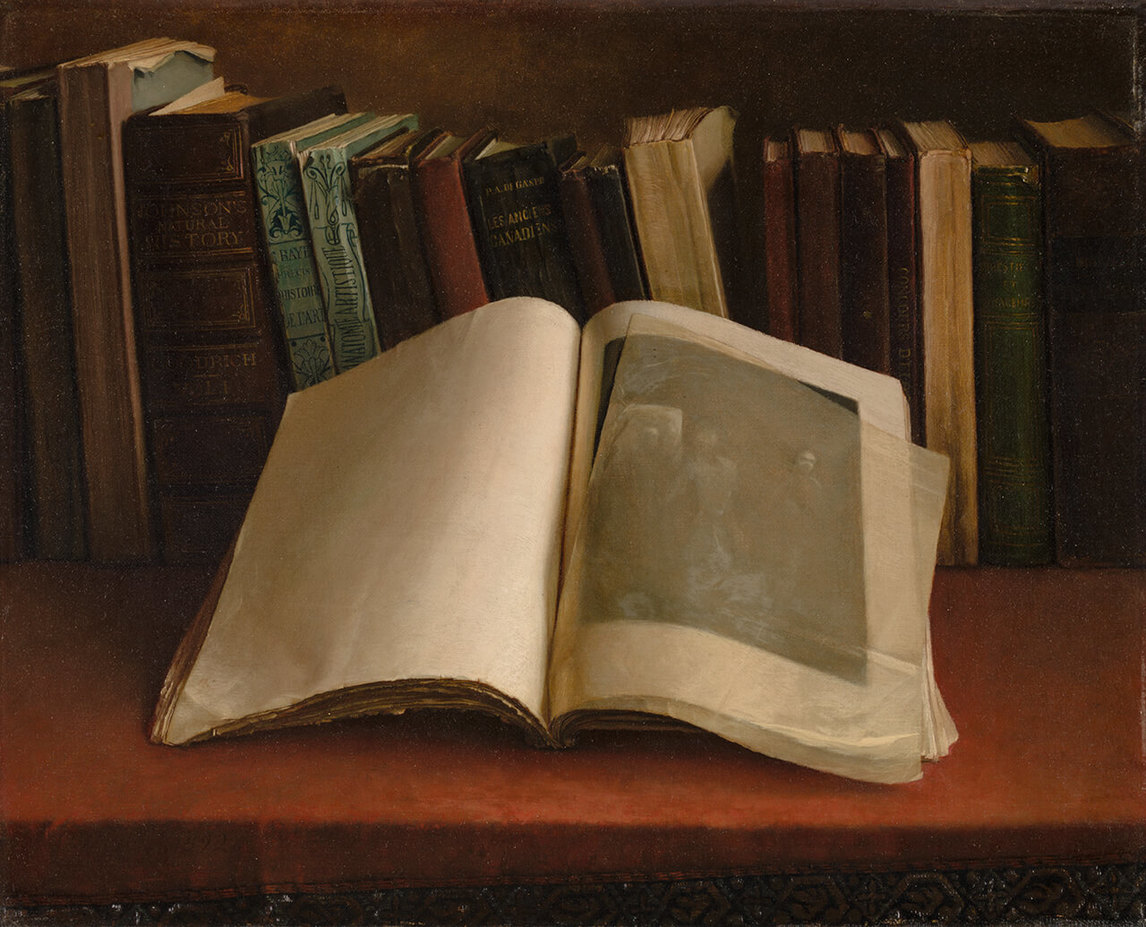

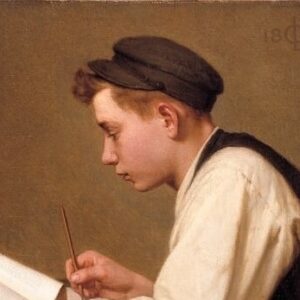

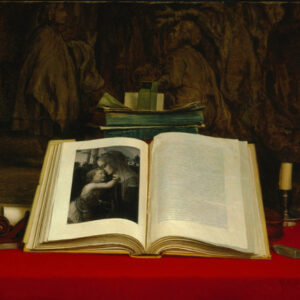

Leduc acquired a large collection of books over the course of his life, which served as the basis of his artistic education and provided him with both knowledge and a wealth of images from which to draw inspiration. He subscribed to several art periodicals from France, England, and the United States, including Studio International, Art et décoration, Arcadia, and the series Masters in Art. His still lifes, such as Phrenology (La phrénologie), 1892, and Still Life with Lay Figure (Nature morte dite “au mannequin”), 1898, and his genre paintings (for example, The Young Student [Le jeune élève], 1894), highlight printed materials, shown either with the tools of the artist’s trade or with adolescents reading. The presence of books in these works underlines the importance Leduc accorded them as a source of enlightenment and a mode of acquiring knowledge about nature and art.

First Commissions

Leduc’s first ventures into painting were in a form of religious art practised by a group of Italian artists active in Montreal. Through the clergy’s contacts in Rome, many requests for church art were passed to a certain number of these painters who came to live and work in Quebec. During most of the nineteenth century, the market for religious painting had been shared among local artists, who had developed a tradition of church decoration that had gradually moved from sequences of individual works (François Baillairgé [1759–1830], Jean-Baptiste Roy-Audy [1778–1848], Joseph Légaré [1795–1855], Antoine Plamondon [1804–1895]) to unified treatments that could embrace the entire architectural decor of a building (Napoléon Bourassa [1827–1916], François-Édouard Meloche [1855–1914]). This group of painters was complemented by Italian and German artists who brought with them the influence of the Nazarenes and, lastly, by religious artists (priests and nuns) who primarily made copies of famous paintings that decorated the churches.

Leduc is believed to have been hired at the age of eighteen (his age is not confirmed by written sources) to paint statues in the studio of Thomas Carli (1838–1906), who sculpted in plaster. In 1886 he was apprenticed to Luigi Capello (1843–1902), a church painter whose work included the Church of Saint-Isidore-de-Laprairie. Born in Turin, Capello had married Leduc’s first cousin, Marie-Louise Lebrun, in 1881. Among other works, he created a (now lost) panorama of the interior of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. During his apprenticeship Leduc decorated the Chapel of Saint-François-Xavier in the Basilica of Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré (destroyed).

In 1892 Leduc was commissioned to complete a project begun by Capello for the Church of Saint-Paul-L’Ermite in what is now the town of Le Gardeur, in Repentigny. At the same time, he assisted the artist Adolphe Rho (1839–1905) of Yamachiche in the production of several murals, including a Baptism of Christ for the Church of Saint John the Baptist in Ein Karem (near Jerusalem, Israel), a place of pilgrimage often visited by French Canadians. Rho was a versatile artist who could turn his hand to anything, a jack-of-all-trades who was quick to respond to the multiple demands of the market. Leduc would remain close friends with Rho and his family.

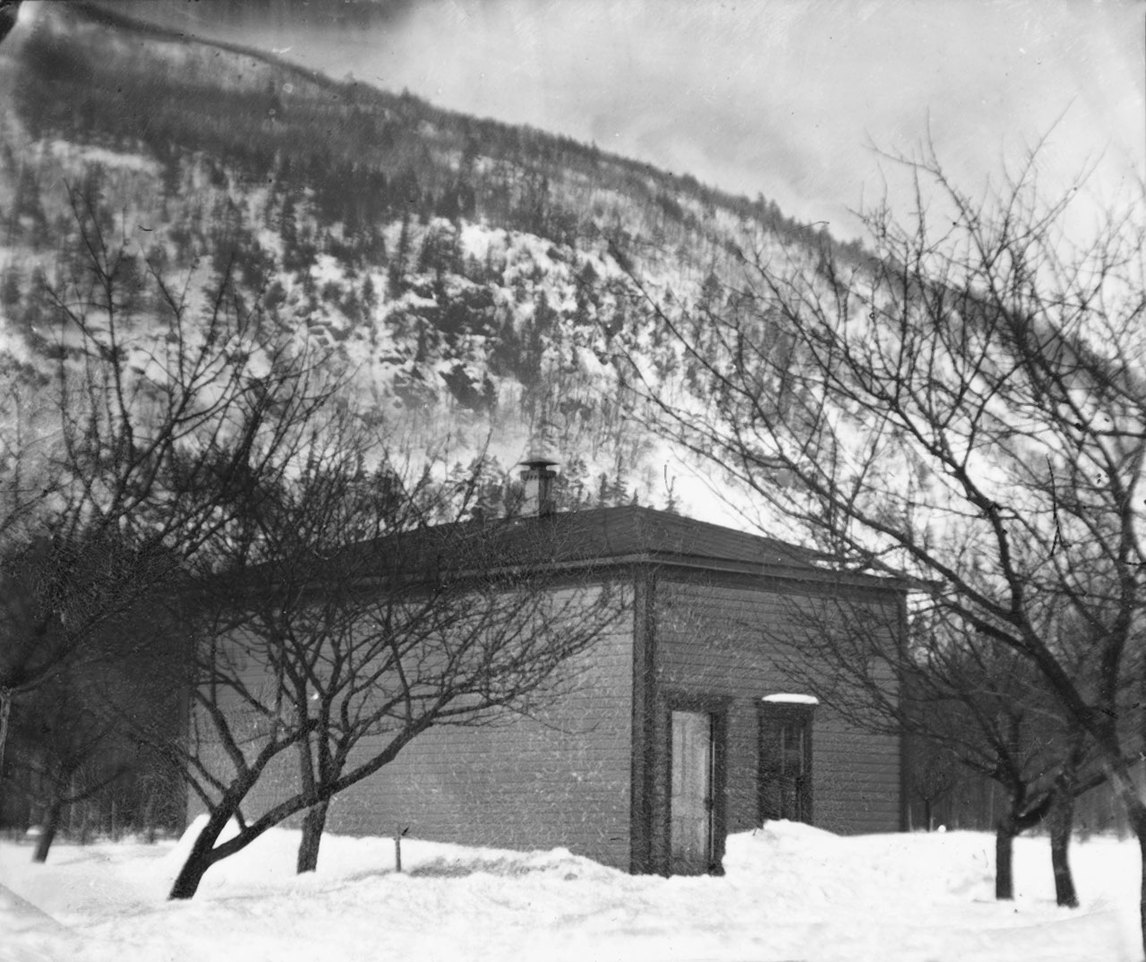

These first contracts helped Leduc acquire the early elements of his art and gave him time to develop his own projects and establish himself as an artist. In 1890 he built a studio on his family’s land. This building, called Correlieu, was later enlarged and became his home.

In Search of His Path

Between 1887 and 1900, Leduc painted a number of portraits, including those of his parents and of the schoolmaster Galipeau, and he began to explore still life, depicting subjects taken from his immediate environment. With Still Life with Books (Nature morte aux livres), 1892, he won the first prize for artists under thirty years of age who were not members of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts. His still lifes were exhibited at the Art Association of Montreal, including Still Life, Violin (Nature morte, violon), 1891 (lost), Still Life with Books (Nature morte aux livres), 1892, and Still Life, Book and Skulls (Nature morte, livre et crânes), 1895 (lost). They attracted critical attention, and most were acquired by collectors.

In 1893, when Leduc was twenty-nine, he received his first important commission. He was hired to create twenty-five paintings for the Church of Saint-Charles-Borromée in Joliette: fifteen depicting the Mysteries of the Rosary; eight showing scenes from the life of Christ; and the figures of David and Saint Cecilia to be placed beside the organ loft. This enormous commission, which Leduc completed in less than a year, was based on “arrangements” or “interpretations” of engravings and photographs of several Old Master works, among them Annunciation by Guido Reni (1575–1642), Assumption of the Virgin by Titian (c.1488–1576), and The Presentation in the Temple by Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640).

Leduc first presented an original ensemble of compositions between 1898 and 1890, for the decoration of the church of Saint-Hilaire. The theme was to be the seven sacraments, the four evangelists, St. Hilary, and an Assumption above the side altars, and the Adoration of the Magi and the Ascension in the choir. To prepare for this important and challenging commission, Leduc travelled to Europe in 1897. After a brief stay in London, he lived in Paris from the end of May until the end of December. Little is known of this trip, except that he rented a studio at 103 rue de Vaugirard and often went to the Louvre. He undoubtedly visited buildings embellished with contemporary murals, in particular the Panthéon, decorated by Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (1824–1898), which influenced his next major project, work for the church in Saint-Hilaire.

Leduc immediately set to work on his decorations for the village church on his return to Canada. The Richelieu Valley, where the artist grew up, had been at the heart of the Rebellion of 1837–38, in which the population rose up to demand greater political and cultural autonomy for French-Canadians under British rule. The dominating influence of the local clergy was counterbalanced by an independent spirit. As a young man Leduc knew several people who had taken part in the insurrections a generation earlier. These events had inspired a novel, Les Ribaud (1898), by Leduc’s friend Ernest Choquette. After its publication, Leduc painted a scene from the book: an ambush of British troops. The novel was adapted for the theatre under the title Madeleine in 1928, and Leduc completed the stage design.

In 1899 Leduc created a series of large graphite drawings based on another novel by Choquette, Claude Paysan (1899), a story set on the banks of the Richelieu. The novelist and his family were strong supporters of the young artist’s work. In 1901 Ernest’s brother, Judge Philippe-Auguste Choquette, ordered three large canvases inspired by the landscape of Saint-Hilaire: The Choquette Farm, Beloeil (La ferme Choquette, Belœil), Harvest (Les foins), and Autumn Tillage (Labours d’automne). Leduc’s friendship with another Choquette brother, Monsignor Charles-Philippe Choquette, a science professor at the Saint-Hyacinthe Seminary, deepened his interest in history, astronomy, and geology.

Leduc was close to the French-Canadian literary world, including the journalist and author Arsène Bessette and, while he was in Paris, the poet and journalist Rodolphe Brunet, whose portrait he painted. His workshop in the Saint-Hilaire church brought him into contact with the young Guillaume Lahaise (1888–1969), a loyal friend who would become an important poet publishing under the pseudonym Guy Delahaye. Leduc was also on good terms with the Campbell family, landowners of Rouville, whose properties included the Saint-Hilaire mountain itself, which they sold in 1913 to Andrew H. Gault.

Religious subjects, portraits, still lifes, genre scenes: Leduc took on every kind of drawing and painting in order to make his name as an artist, and it was through illustration that he would enter fully into landscape painting.

Rising Fame

Leduc’s early years are sparsely documented, but that changes completely after the 1900s. He became his own archivist, creating a rich chronology of his career. As he became increasingly aware that his artistic approach was personal, Leduc amassed a complete file of documents related to his interests and achievements, and kept a record of every artwork he created. His personal history and the record of his art seem to be one and the same; he appears to have had no life outside his work. All of his activities and each of his friendships contributed to the realization of his painting.

Leduc began to receive important commissions, such as his Portrait of the Honourable Louis-Philippe Brodeur (Portrait de l’honorable Louis-Philippe Brodeur), 1901–4, the Speaker of the House of Commons. His reputation grew with his participation in not only the annual show of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts from 1893 onwards, but also exhibitions mounted by the Ontario Society of Artists, where he first showed in 1902. There, he exhibited, among other works, Still Life, Study by Candlelight (Nature morte, étude à la lumière d’une chandelle), 1893, and Madame Ernest Lebrun, née Adélia Leduc, the Artist’s Sister (Madame Ernest Lebrun, née Adélia Leduc, sœur de l’artiste), 1899. Leduc was part of a generation of painters who emerged in the 1890s. He and b (1863–1949), Joseph-Charles Franchère (1866–1921), Ludger Larose (1868–1915), Joseph Saint-Charles (1868–1956), and Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté (1869–1937), for example, shared the same network.

The number of commissions Leduc received for religious murals increased greatly during the 1900s, which left him with little time for easel painting. In 1901–2 he created the decor of the Church of Saint-Michel at Rougemont, made up of nineteen large compositions (now destroyed). In 1902 he established a partnership with his cousin Eugène L. Desautels to expand the range of his activities outside the province, a connection that led, in 1902–3, to decorating St. Ninian’s Cathedral at Antigonish, Nova Scotia (overpainted), and the Halifax Chapel of the Sisters of the Sacred Heart in 1903 (destroyed). Two commissions in New Hampshire, for the Church of Sainte-Marie in Manchester, 1906 (destroyed), and for St. Mary’s in Dover, 1907–8 (destroyed), came to Leduc from clergy serving communities of French Canadians who had emigrated to the United States. He undertook the decoration of the Church of Saint-Romuald, in Farnham, 1905–7 (partly overpainted); the choir of the Chapel of Notre-Dame-de-Bonsecours, Montreal, 1908 (dismantled); a painting for the high altar of the Church of Saint-Barnabé-Sud, 1910–12; and the decoration of the Church of Saint-Edmond, in Coaticook, 1911 (destroyed). These projects gave Leduc opportunities for both formal and iconographical experimentation.

On August 31, 1906, Leduc married his first cousin Marie-Louise Lebrun, widow of his former mentor Luigi Capello. The couple moved into Correlieu and received their friends there. Not much is known about the relationship between husband and wife, except that the families of the two sisters (the mothers of Marie-Louise and Ozias) were very close, and that Leduc had lived with the Capellos when he stayed in Montreal in the 1890s, at a time when Luigi was often away working in the United States.

Did their feelings for each other date from their childhood, or did they develop during the artist’s visits to Montreal? Was Leduc influenced by the thought that in marrying her he would be giving material support to his kinswoman, who was also the widow of his first teacher? The bride was forty-eight years old at the time of their wedding, and the groom, forty-one. Was their union based on reason or passion? Marie-Louise Lebrun-Leduc certainly had some artistic ability and is known to have made flower paintings. Friends’ testimonies suggest the couple lived in great harmony, with Madame Leduc doing everything to support her husband in his work and make his life at home as easy as possible. Visitors noted Marie-Louise’s warm and welcoming hospitality.

The Symbolist Years

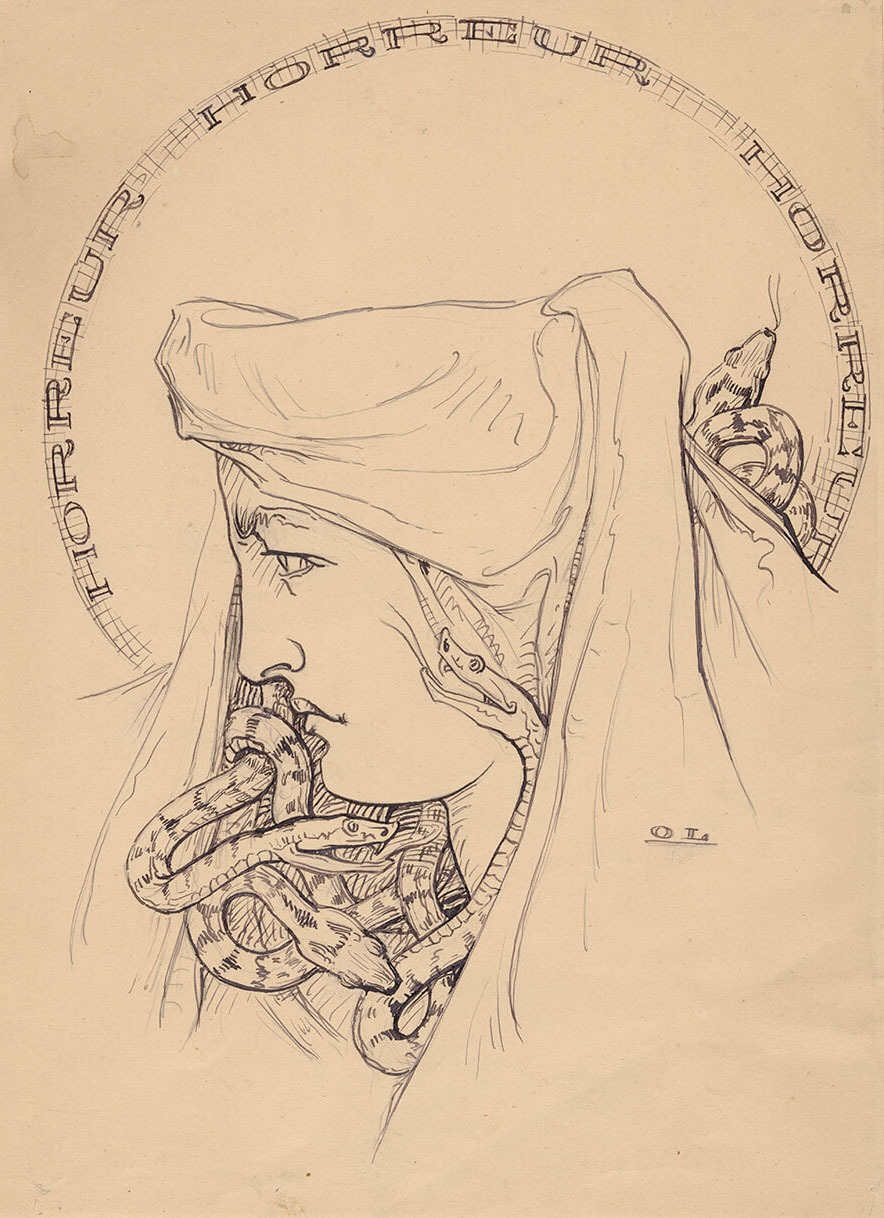

During his time in Paris, Leduc became interested in Symbolism, which appears in his treatment of feminine figures. He made multiple drawings and paintings devoted to Erato, the muse of erotic poetry, whom he associated with a mysterious force of nature. These works include Study for Erato (Sleeping Muse) (Étude pour Érato [Muse endormie]), 1898, and Erato (Muse in the Forest) (Érato [Muse dans la forêt]), c.1906. His self-portrait of 1899 is also painted in the Symbolist style. Leduc’s studies affected his religious decorations and culminated in a series of Symbolist easel paintings begun in 1911. In 1912 his illustrations for Guy Delahaye’s poetry collection “Mignonne, allons voir si la rose” . . . est sans épines served as a springboard for this renewed interest. Some of Leduc’s images appear in the form of ironic rebuses, for example, Horror, Horror, Horror (Horreur, horreur, horreur), 1912. The artist also included allegorical elements in his portraits of the poet painted in 1911 and 1912.

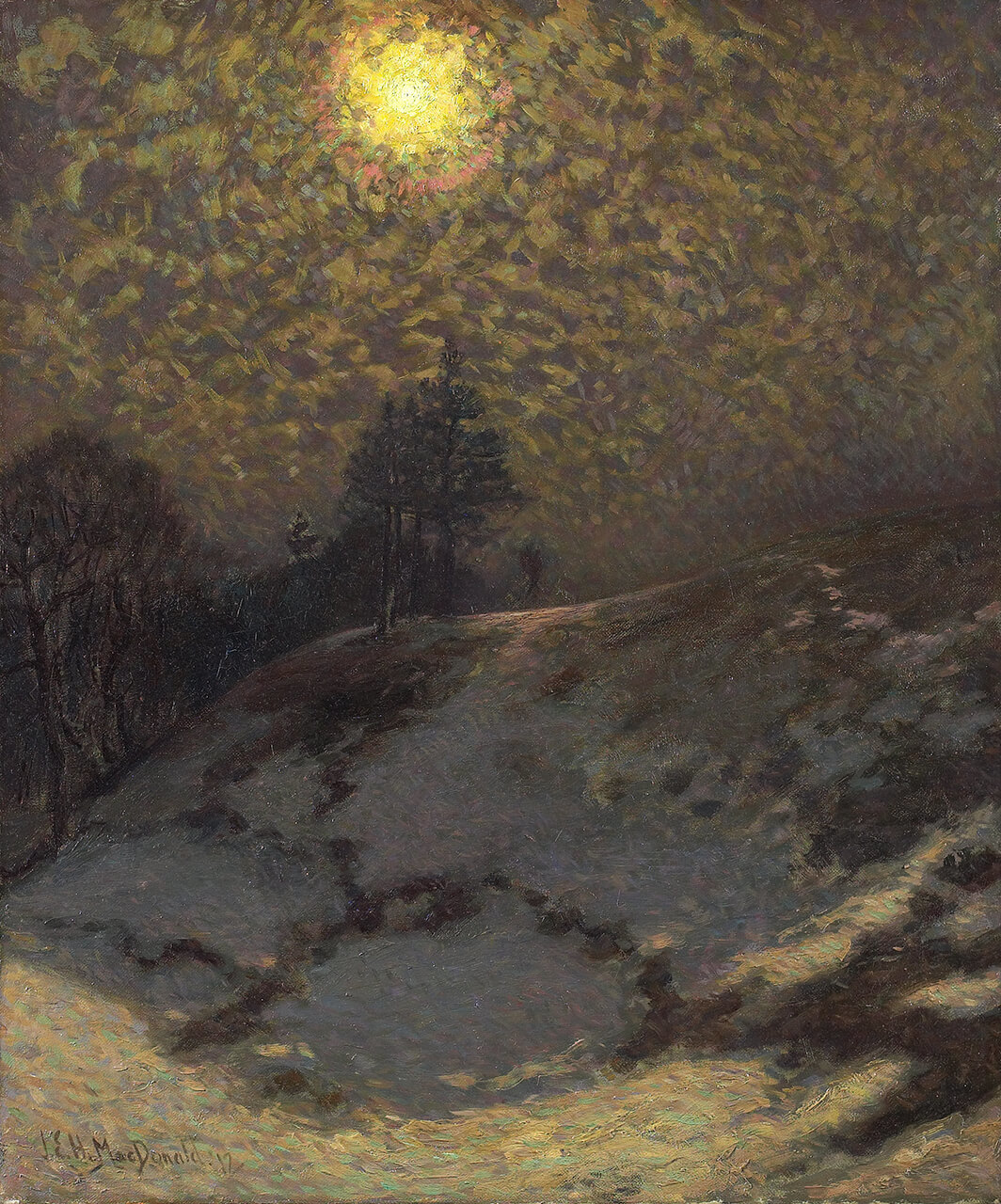

The period 1913 to 1921 witnessed the creation of a sequence of nine clearly Symbolist landscapes, from Blue Cumulus (Cumulus bleu), 1913, to Mauve Twilight (L’heure mauve), 1921. These paintings are undoubtedly the most personal of Leduc’s oeuvre, based on observations of the surrounding landscape. They are invested with visual concepts of great complexity. His close attention to the treatment of his subjects results in pictorial surfaces that seduce the eye and reveal an idealized conception of nature. Green Apples (Pommes vertes), 1914–15, and Gilded Snow, 1916, were acquired by the National Gallery of Canada.

That same year, Leduc was elected an associate member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts. His work continued to be praised by his contemporaries: the critic Albert Laberge (1871–1960) reported that the painter A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974) had remarked of Green Apples: “If this man were surrounded by a group of painters who stimulated him, who pushed him to produce, he would be first among us, because he has originality and he is a marvellous colorist.” It is true that Leduc did not explore the land in the way the Group of Seven did, but his interest in geology and representing nature as precisely as possible brings him close to the sensibility of J.E.H. MacDonald (1873–1932; see Early Evening, Winter, 1912, or The Tangled Garden, 1916). In each of his compositions, Leduc altered the perspective and point of view in order to stimulate new ways of looking. Perhaps the most extreme example of this Symbolist treatment is Mauve Twilight, which depicts the monumental simplicity of an oak branch in snow.

The Painter of Saint-Hilaire

In 1913 Leduc made plans to build a larger house on his land. Although he and his wife would never live there, he installed a studio in the 1920s, which he occupied until the 1940s. He took over the family orchard, and from then on devoted his time to it in spring, when the year’s crop was being prepared, and in autumn, during apple picking season, which provided an alternative source of revenue. The frequent fast trains that ran between Saint-Hilaire and the city allowed Leduc to stay in touch with his circle in Montreal. Reliable postal service via this same rail link made it easy for him to maintain regular communication with friends. Leduc was an assiduous correspondent.

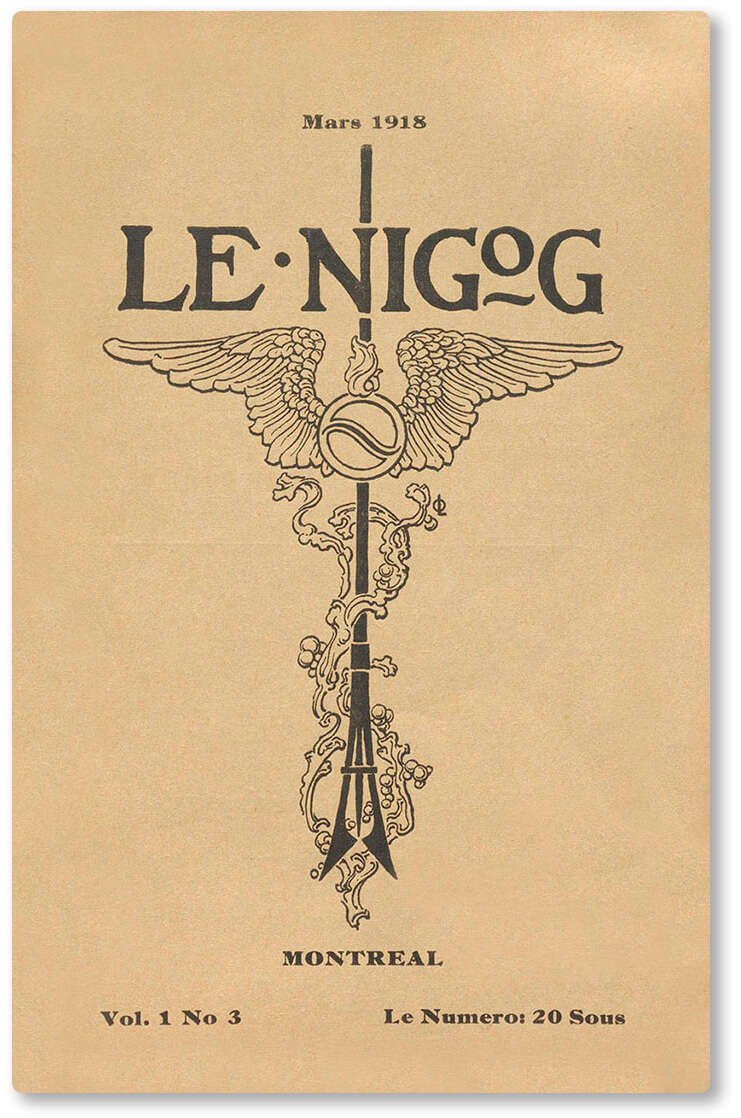

In 1918 Leduc contributed to a publishing venture, creating the cover design for a new interdisciplinary magazine, Le Nigog. Founded by the architect Fernand Préfontaine (1888–1949), the writer Robert de Roquebrune (1888–1978), and the critic and musician Léo-Pol Morin (1892–1941), it lasted only a year. It brought together reviews and essays on architecture, literature, music, theatre, and the visual arts, and took a critical look at controversial issues of the day, such as regionalism and the choice of subject matter in art.

Leduc had a gift for attracting younger, innovative spirits, who in turn were inspired by his work. Through them, he became a part of the Montreal artistic elite and met, among others, the painter Adrien Hébert (1890–1967) and the architect Ernest Cormier (1892–1941). Leduc was a good conversationalist whose wit was celebrated, and he received many visitors at Correlieu. According to Fernande Choquette, daughter of Ernest Choquette, the conversations of the group were “gay, witty, amusing, or profound, punctuated by bursts of laughter and over-the-top emotions. They often involved inquiries into the deepest recesses of the heart and soul, verbal juggling, and endless discussions about the nuance of a shade of green, the density of shadows in the interior of a barn, or the exact depth of a fold in an angel’s tunic.”

Leduc’s sense of humour was widely known, and many examples of it can be found in his writing. In his Sherbrooke Journal, for instance, a diary he kept between 1922 and 1937, he noted on April 5, 1922: “Went to the Cinema to see ‘La Lumière éternell’ [sic] that everybody is talking about. It was like a wax museum in motion. I stayed to the end, but I was delighted to see Christ rising up to heaven, from where he will return to judge the ‘Cinema’ and its newest tormentors.” The next day, April 6, he wrote: “The Hon. J.N Francoeur, President of the Legislative Assembly, has informed me in a kind letter that his portrait makes him look too old. Apparently, everyone thinks so, even connoisseurs. We’ll make him younger later.”

Leduc made many friends in these years, but one especially faithful connection stands out: Olivier Maurault (1886–1968), the Sulpician priest and artistic director of the Saint-Sulpice Library, whom Leduc met in 1915. Their friendship lasted forty years and was marked by many demonstrations of admiration, affection, and confidences, which are expressed in an abundant correspondence. In 1916 Maurault mounted an exhibition of Leduc’s paintings at Saint-Sulpice, the artist’s first solo exhibition and the only one of importance during his lifetime. It included forty works, some of them recent, such as Blue Cumulus, 1913, Green Apples, 1914–15, and The Concrete Bridge (Le pont de béton), 1915. In 1921 Maurault published a booklet on Leduc’s decoration of the Sacré-Coeur Chapel in the Church of Saint-Enfant-Jésus in Montreal’s Mile End, and in 1938, when he was rector of the Université de Montréal, he awarded the artist an honorary doctorate. Leduc painted or drew several portraits of his friend between 1918 and 1924.

During this period of intense creativity Leduc also found time to contribute to his community. In 1918 he became president of the Saint-Hilaire school board, an appointment that was renewed for the next three years. He took a particular interest in the purchase of books and improvements to the playgrounds. From 1924 to 1937 he was a municipal councillor for the parish of Saint-Hilaire, where he took on responsibilities primarily for route planning, road repair, and the installation of power lines.

Leduc set up a committee for the beautification of the parish, once again with the goal of creating a more attractive living environment for his fellow citizens. He was particularly interested in planting trees to improve the setting around buildings. He took on other civic responsibilities too: from 1923 to 1927 he was a member of the Saint-Hilaire Sports Association, and in 1925 he chaired the Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day committee. In 1931 he took on an additional role as warden of the parish.

Leduc’s popularity and the diversity of his work attracted the attention of opposing ideological groups, whose supporters interpreted his message in different ways. As much as his investigations of Symbolism interested young intellectuals, so were his rural subjects read by the clerical and nationalist elites as praise for the values they championed, which were oriented toward the soil and the definition of the French-Canadian nation. Leduc never took a formal position on these divisive issues or a political stand. Some of his clients, such as Father Philippe Perrier of Saint Enfant-Jésus, were close to the political journal L’Action nationale, which was edited by the priest and historian Lionel Groulx. Father Albert Tessier, priest and filmmaker, was also a frequent visitor to Correlieu. Other regulars included the young Automatistes, whom Leduc encouraged, and who were introduced to him by Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960). The list of those who received gifts of drawings from the series Imaginations, 1936–42, confirms that Leduc did not choose his friends based on their sociopolitical leanings, but rather on the strength of the personal ties he had established with them as individuals and on the elective affinities they shared.

When a new generation of artists appeared on the scene—young painters who had trained at the school established by the Art Association of Montreal, including members of the Beaver Hall Group and, soon after that, students from the École des beaux-arts de Montréal (founded in 1922)—Leduc’s work began to seem less relevant to the general public. At the same time as his work and status were becoming recognized as forming part of the history of painting in Quebec and Canada, Leduc was receiving fewer commissions, a situation that a harsh economic climate would worsen. He was revered for taking part in the revival of religious art, which had brought modernity into the art commissioned by the church. It was in this connection that he was introduced to Maurice Denis (1870–1943) when the French painter passed through Montreal on October 1, 1927, and also to the theorist, artist, and Dominican father Marie-Alain Couturier (1897–1954), in February 1941, yet these encounters had no significant effect on his thinking.

Within the last thirty years of his life Leduc created two of his most important church decorations, the Bishop’s Chapel in Sherbrooke, 1921–32, and the Church of Notre-Dame-de-la-Présentation in Shawinigan, 1942–55. In both works, he pushed further the reflections he had begun in his paintings for the Sacré-Coeur Chapel (baptistry) in the Church of Saint-Enfant-Jésus in Mile End, 1917–19 (overpainted), and in the baptistry of Notre-Dame de Montréal, 1927–29, as well as in pictures created for the Church of Saint-Raphaël in Île Bizard, 1920–21, and the Church of Sainte-Geneviève in Pierrefonds, 1926–27.

These commissions came to him through his wide network of friends, including an architect (Louis-N. Audet), priests (Adélard Dugré and Albert Tessier), and sponsors (Fathers Philippe Perrier, Alfred Nantel, Louis Bouhier, and Arthur Jacob, along with Fred and Florence Bindoff). A new generation of artists was now in frequent attendance at Correlieu, among them Rodolphe Duguay (1891–1973) and the young Automatiste painters Jean Paul Riopelle (1923–2002) and Fernand Leduc (1916–2014), all of whom deeply admired the older artist.

Leduc enlisted Paul-Émile Borduas to assist him with the Sherbrooke project, and gave the young painter generous encouragement and counsel. The early years of the apprentice’s career followed the same path as his teacher’s: after receiving his diploma from the École des beaux-arts de Montréal, Borduas travelled to France to study at the Ateliers d’art sacré. Leduc and Borduas worked together on the decoration of the churches of Saints-Anges in Lachine (1930–31) and Saint-Michel in Rougemont (1933–35). Beginning in the 1940s the younger artist changed course, taking the path of nonrepresentational art, but the two men remained close, even after the publication of the notorious Refus global, an attack on the status quo in Quebec.

As orders for paintings slowed down, Leduc took on a number of other activities. He was invited to give public lectures, which testify to his faith in art and its civilizing role. His writings about his work, along with some poems, were published in the journals Amérique française and Arts et pensée. Also at this time, between 1936 and 1942, he undertook a series of landscape drawings, titled Imaginations. These small-format works on paper are a sum total of the images and subjects that had interested him throughout his career, and which he recreated from memory. Produced as gifts for friends, the drawings show at least part of the network that surrounded Leduc at the time of his widowhood in 1939.

The Last Project

Leduc had one more important contribution to make. In 1941, at the age of seventy-seven, he was asked to create the decor for the Church of Notre-Dame-de-la-Présentation at Shawinigan. Assisted by Gabrielle Messier (1904–2003), Leduc would devote the last ten years of his life to the execution of this project, in which he created a synthesis of the different themes that characterized his mural decoration and, as always, contributed to the renewal of religious art.

Leduc combined the central theme of Christianity, from the sacrifice of Christ on the cross to the prefiguration of the Eucharist, with four subjects drawn from the New Testament that related to the theme of the salvation of humanity. He linked them with two scenes from the history of Shawinigan, and with four paintings that pay homage to the workers of the region: scenes from the lives of clearers of the land (the sower and the woodcutter) and factory workers (workers in metal and in pulp and paper). The compositions are cut-up and mounted canvas, and the tributes to the workers whose efforts helped pay for the commission display some of the technical and iconographic innovations of this ensemble.

Leduc’s longevity and the originality of his work would reinvigorate his stature and result in renewed recognition from the art market, museums, and critics. In 1945 the Musée de la province de Québec (today the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec) brought together twenty-five of his paintings, including Portrait of Guy Delahaye, 1912, and Green Apples, 1914–15. In 1954 the Lycée Pierre-Corneille in Montreal exhibited fifteen works in a mini-retrospective organized by Gilles Corbeil, which included The Young Student, 1894, and Mauve Twilight, 1921. In the summer of 1954, Corbeil also edited a special issue of Arts et pensée devoted to Leduc. Nine authors contributed texts, among them the artists Borduas, Claude Gauvreau (1925–1971), and Fernand Leduc. In addition, Jean-René Ostiguy (1925–2016), curator at the National Gallery of Canada, began putting together a travelling exhibition of forty-one works, which was to tour the country beginning in December 1955. Leduc would never see it. He died on June 16 of that year at the Saint-Hyacinthe hospital, where he had been since the previous December. Many of his friends assembled to pay their final homages to him at his funeral in Saint-Hilaire.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements