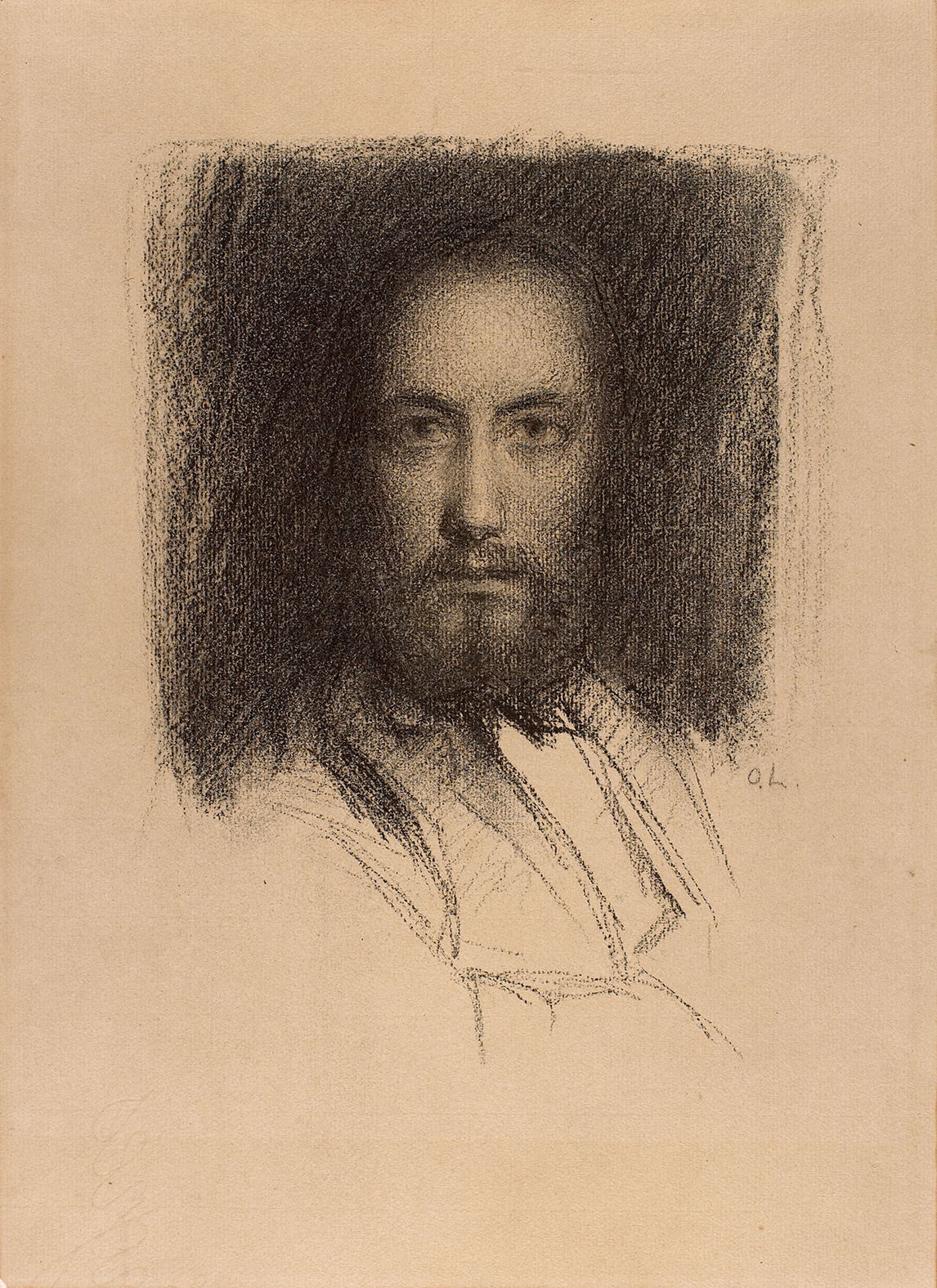

My Portrait 1899

Ozias Leduc, My Portrait (Mon portrait), 1899

Oil on paper, mounted on wood, 33 x 26.9 cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

This small oil painting reveals a moment of intense concentration. The artist no doubt used a mirror to observe himself for this self-portrait. He looks straight into the mirror (and therefore at the viewer), with his chest and shoulders turned slightly to the side. The position of the white shirt indicates that his body is angled away from the painting surface, toward which he must turn in order to see and reproduce what he is observing. The artist’s face, posed atop a black costume, erupts from a sombre background.

It is not, however, the act of painting that is Leduc’s focus here. He does not intend a realist or trompe l’oeil likeness of his own image. This face has become an expressive territory, masked by the chiaroscuro painting technique: its lower part, with its sensual lips, disappears under a dark, dense beard. Crimson cheeks seem to have been ripped by the strokes of the palette knife. The bridge of the long, straight nose appears as the axis of a stretched face; what we see, above all, are the eyes. It is this deep and penetrating gaze, grave and mysterious, that animates the face and its wide, bare, illuminated brow, defined by thick impasto layers of paint.

Leduc’s face unites a series of opposing forces: a voluptuous and carnal world presented in semi-darkness, and a brighter and more luminous world associated with his psyche. The self-portrait brings together the world of ideas, in the upper part of the face, and that of the senses, the corporeal. The lines of the drawing have disappeared under the work of the brush and palette knife, while the background is impenetrably dark, drawing the viewer’s eye to the brighter sections, which are nonetheless also a part of this shadowy environment. The artist seems to emerge from a world of darkness to study his own physiognomy and, at the same time, to allow the viewer to observe the artist as he turns inward with a determined and fixed gaze.

In 1899, when Leduc painted this self-portrait, he was deeply absorbed in the task of decorating the church in Saint-Hilaire. It seems to have been a time of great introspection, as evidenced by the self-portraits he completed that year. One of them is a photographic self-portrait, which shows him taking his own picture, in effect becoming paired with the camera. Here, he presents himself as an artist who foregrounds elements of his own practice and reflects on the conditions in which the work came to exist. Although the role photography played in Leduc’s work as a painter was primarily documentary, it enabled him to assert that method, process, and inspiration are intimately linked.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements