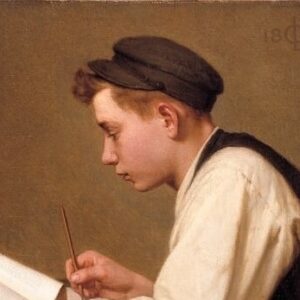

Madame Ernest Lebrun, née Adélia Leduc, the Artist’s Sister 1899

Ozias Leduc, Madame Ernest Lebrun, née Adélia Leduc, the Artist’s Sister (Madame Ernest Lebrun, née Adélia Leduc, sœur de l’artiste), 1899

Oil on canvas, 42.8 x 32.5 cm

Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, Quebec City

The slender head of a woman is set above wide shoulders fitted into a gigantic blouse adorned with fine embroidery. The liveliness of the woman’s gaze contrasts with the barely lighted wall behind her, creating a pictorial space absent of depth. She wears a long black skirt and seems isolated in this dim room, her body disappearing under the dark and oversized clothing. Her blouse, in tones of white with brown shadings, occupies the entire space, enlarging her torso. She seems worried: she has put down her lacework, needle, and thread, and holds tightly to the straight-backed chair on which she is sitting.

At first sight the sturdy frailness of the model in this portrait is disconcerting. Adélia, Leduc’s favourite sister, was six years younger than him. In 1895 she married her first cousin Ernest Lebrun, brother of Ozias’s future wife. The Lebruns and the artist were very close. He appreciated their human qualities and their remarkable abilities. Like Adélia, Ernest had many talents. He was a mechanic and electrician who also devoted himself to photography, a subject that he and the painter discussed often.

In this painting Adélia submits to the game, serving as a prop for her overflowing garments. The folds of the ample sleeves, made of a material both thick and supple, transform themselves into multiple configurations. The folds and pleats are like waves surging and breaking over her arms and chest—a heavy, chaotic expression of the feelings of the body they enclose. That body, held still and reserved, arms tense, almost disappears under the pale blouse whose complicated billows seem to open out toward the infinite.

The delicate lace ruffles at the wrists and bodice become shifting points of departure for hollows, perforations, scallops, arabesques, and dense fractured movements traversing the arms and the breast. This multiplication of effects suggests a landscape undergoing transformation. The face, which is present and absent at the same time, exposes the whole past and future of the person herself, actualized by a clothed and inaccessible body. Adélia’s blouse recalls the tradition of women’s costumes in Venetian painting, where fashion became a means of claiming ownership of a woman’s body and the fullness of a garment expressed the richness and complexity of the model.

It is this elevated and spiritual movement that the sculptor Bernini (1598–1680) captures in the clothing of the saint in his sculpture Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1647–52). Leduc owned an illustration of this work and had also made a copy of it (1934). The philosopher Gilles Deleuze reflected on the movements of the folds inspired by the Baroque style to express their richness and profundity. He writes: “It [the Baroque] radiates everywhere, at all times, in the thousand folds of garments that tend to become one with their respective wearers, to exceed their attitudes, to overcome their bodily contradictions, and to make their heads look like those of swimmers [ . . . ] folds of clothing acquire an autonomy and a fullness that are not simply decorative effects. They convey the intensity of a spiritual force exerted on the body, either to turn it upside down or to stand or raise it up over and again, but in every event to turn it inside.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements