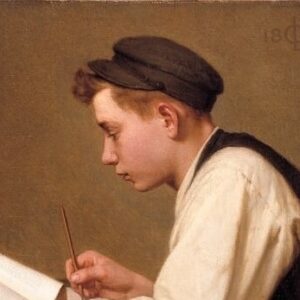

Boy with Bread 1892–99

Ozias Leduc, Boy with Bread (L’enfant au pain), 1892–99

Oil on canvas, 50.7 x 55.7 cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

How can a work of art be heard? Can its rhythm become visible, its movement and accents rendered musically perceptible to the senses? The genre scene Boy with Bread offers answers to these questions. This picture was very slowly worked out, conceived in 1892 as a large-format drawing and completed seven years later, in 1899. The curved posture of the boy as he bends forward, his relaxed and at the same time attentive demeanour, convey a serene melody and quiet air that invites a sense of calm, of dream. A slow compositional movement is sketched, suited to his wandering imagination.

The repetition of curved forms fitting into one another—the bowl, the hat, the child’s body—creates a linked sequence that invites the viewer to move around the image. This circular movement is supported and structured by the angles of the furniture. The application of paint sharply highlights and accentuates the crust of bread and, similarly, the design emphasizes the folds and creases of the boy’s shirt at his shoulder and elbow. The beige and brown tones of the wooden table and chair bring the ensemble together and are warmed by the red and pink highlights of the clothing. The outlined contours of the hand and face introduce another kind of harmony to this sober composition.

The tension of this picture exists between youth and the passage of time (signs of wear, a meal just begun). The balance of Leduc’s compositions often rests on this point of tension. As he wrote in 1943 to his friend and former student Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960): “Art teaches, informs. It reveals the soul. There is no doubt that it has the power to transform the chaos of the unconscious into an ordered cosmos. It leads us away from disorder, suffering, and imbalance toward stability, harmony, and joy.”

Against the background melody certain details emerge—the textures of the piece of bread and the bowl, the rips in the shirt—that suggest a different rhythm, a concentration of elements that enchant the eye and add richness to the movement of the composition. Leduc reminds us that concentration, contemplation, and imagination are useful tools for penetrating a work of art so that it can be fully understood, grasping the overall lines of the whole while at the same time giving attention to the details.

Before it became part of the collection of the National Gallery of Canada, the work belonged to Leduc’s friends M. and Mme Édouard Clerk of Saint-Hilaire. Mme Clerk, née Fernande Choquette, was the daughter of Dr. Ernest Choquette. She was a regular visitor to the studio and a close friend of the artist, about whom she wrote some charming commentary. In 1917 Leduc created a portrait of her in low-relief plaster as a wedding gift.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements