Mary Pratt was a Photorealist painter, using meticulous detail inspired by the precision of lens-based images to represent light and surfaces. She worked from photographs, often tracing her compositions straight from slides projected onto canvas or paper. She strove to reproduce the photographic image accurately, for it served to capture the play of light that sparked her interest in the first place. Often, years would pass between the photograph being taken and Pratt’s selection of it as her subject. In her later career Pratt began to work more in mixed media, combining chalk, pastels, and watercolour into large-format works on paper. She completed just one printmaking series in her career.

Painting the Photograph

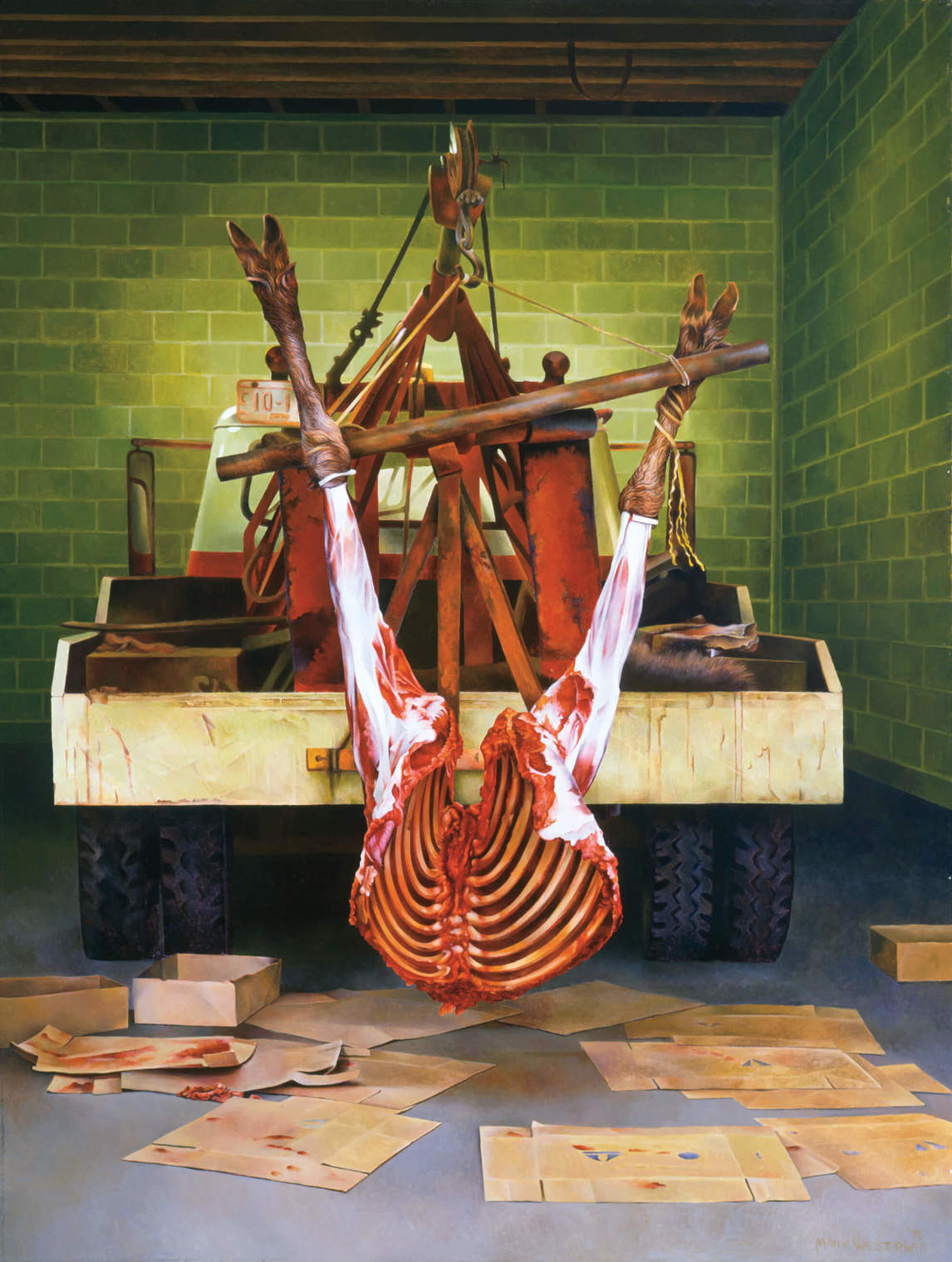

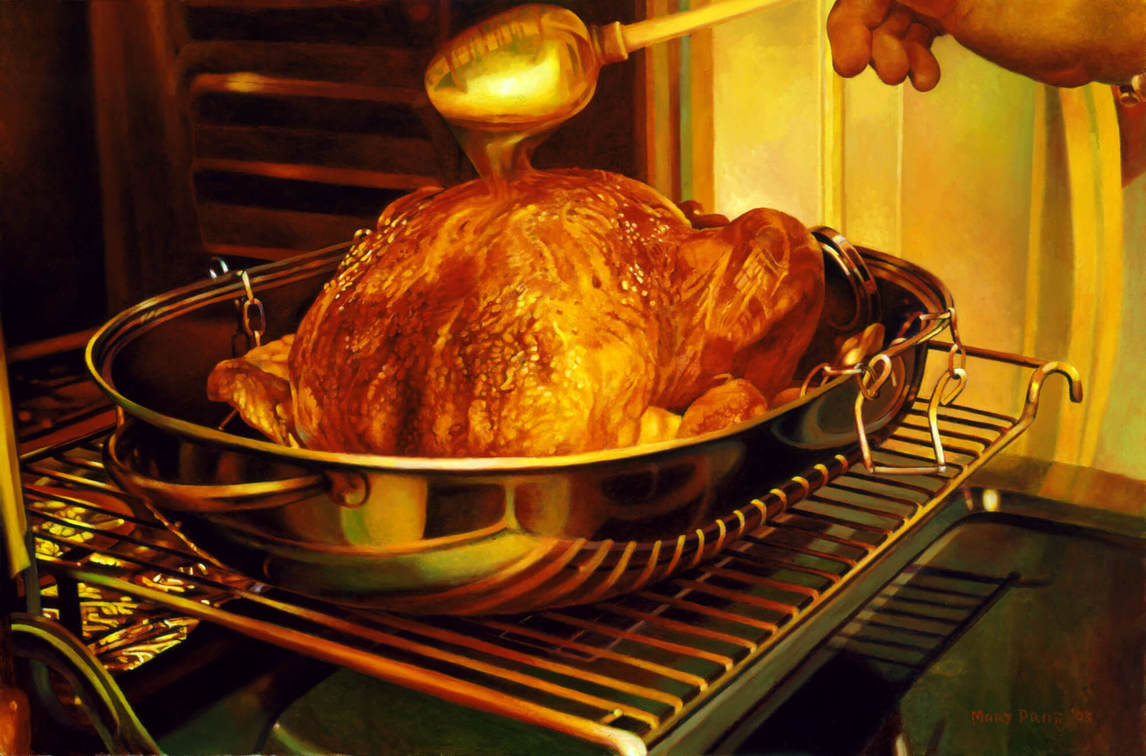

Mary Pratt’s style was based in the careful reproduction of her source materials, which since the late 1960s were invariably photographs. And her subject, despite the parade of household tools, wedding presents, and foodstuffs, was actually light. Her realism was less about depicting things than about emotions, physical reactions, or states of mind: a flash of beauty, repulsion. “So I was cooking and cleaning and ironing, and doing what you do. But the world came to me. It just popped at me,” said Pratt. “I figured that I wasn’t going to paint anything that didn’t affect me personally and physically.”

Pratt painted in oils, after sketching in the bare bones of her composition. Often she would project the image onto her canvas and trace the image directly. She used small sable brushes, intended for watercolour painting, and worked in a series of cross-hatched, tiny strokes, laying down colour from a top corner of the panel to the bottom, working in as many layers as needed to get the lifelike quality she was seeking. This careful buildup of thin layers meant that there were no brush strokes visible in her paintings.

She worked with a slide viewer next to her easel, its large screen showing the image she was working on. That illuminated image was what she painted. This was not an unknown practice, of course; artists had been using photographs as references since the invention of photography, and the camera obscura, a rudimentary means of projecting light onto canvas, had been available to artists since the Renaissance. Unlike Pratt’s most famous teacher, Alex Colville (1920–2013), she did not create a geometric underpinning for her paintings, choosing to do most of her composition, with the exception of some editing, in the camera itself. “Measuring, a creation of space, doesn’t really interest me at all,” Pratt wrote in 1993. “When I have to use grids, etc., I haven’t understood it, and it never seemed important to me at all.”

“To me, the surface is the given reality,” said Pratt, “the thin skin that shapes and holds those objects which we recognize as symbols.” Reality, of course, is both a concrete and mutable subject. No two people see the world similarly, and the instant one starts to explain or define reality as a fixed thing, one is on unsure ground.

The Technique of Realism

Twentieth-century art largely put realism in the conservative camp, a reactionary response to more abstract, avant-garde approaches to image making. In his 1959 book Painting and Reality, the French-born philosopher Étienne Gilson dismissed all forms of painting except for abstraction as hopelessly retrograde—and, echoing the modernist preference for subjectivity and psychology, not sufficiently real. Gilson claimed that there was a difference between the “real” and the “visible.” Yet Gilson, writing in the heyday of Abstract Expressionism, creates a false duality between “imitative” and “creative.” Sixty years later this does not ring true. We know that representational art is not just imitation.

Realism in fine art is perpetually fraught with existential contradictions. As art historian Linda Nochlin writes: “A basic cause bedevilling the notion of Realism is its ambiguous relationship to the highly problematical concept of reality.” But nevertheless, that ambiguity, and that problematic concept, are central to the art of Mary Pratt. Perhaps the problem with realism is actually one of language—that a supposed realist painting is no more or less real than an abstract one. That is, this problematic concept begins not with Mary Pratt, but with us.

The idea that realism presents the world as it supposedly is has roots in the first realist movement that swept the Western art world, led in the nineteenth century by French painter Gustave Courbet (1819–1877). Before that, representational painting certainly existed, but it was not labelled as “realism.” And so Courbet’s realism was not about style (for in nineteenth-century France most artists were realists to modern eyes) but about showing things as Courbet felt they really were—an aspiration that was social and political. Courbet painted subjects, such as poor peasants and, famously, female genitalia in The Origin of the World,1866, that the bourgeois art world of France found hard to look at. In this way, Courbet used his realism for a radicalized purpose.

In nineteenth-century academic painting there were strict hierarchies among genres, with Courbet’s chosen mode—history painting—at the pinnacle. Women, who were not allowed by the academies to draw from the nude male model, tended to be relegated to what were considered lesser genres, such as still life. That gender-based differentiation survived well into the twentieth century, when the male painters of early modernism leading on into Abstract Expressionism were ascribed heroic and often macho characteristics.

Women were at the periphery of these movements, approaching a semblance of equal treatment only with the advent of feminism and its political approach to artmaking. In painting representationally, Pratt (notwithstanding the example of her male teachers who were realists) was doing what was expected of a young female artist in the mid-twentieth century, certainly in Canada. But she was also making visible a marginalized reality. Mary Pratt’s focus on the goriness of domesticity, and on the life of a woman at home caring for her children and her husband, surrounded by the trappings of a middle-class upbringing, can be read as realist social commentary. Like Courbet, Pratt wanted to show the world, or at least her world, warts and all.

From Projection to Painting

Mary Pratt’s observation of her subjects unfolded over time. She recounted that her process evolved in stages: “I see something that grabs me, and I do the photography—that’s the first thing. It gets sent off to Toronto or wherever to be processed, and then when all of these slides come back, I’ve forgotten that first jab, that first jab of enthusiasm.”

Slides are developed from photographs, printed diapositively on a transparent base and placed in cardboard or plastic mounts, and placed into a carousel for projection. In the mid-twentieth century, slides were affordable to produce and widely used by artists, art historians, and designers, as in their 35mm format they allowed for high-resolution reproduction and projection.

Once Mary Pratt had her slides back from the processor, she would spread them out on a light table to look at them with new eyes, “to see if there’s anything there that I remember.” The element of discovery that this approach brought with it was important to her. “I have the opportunity again to decide what to do with this whole thing. And that’s kind of exciting, because you can only hope that the slides you’ve taken will remind you of that moment when you thought the whole thing was going to be worthwhile, and that you were going to do something wonderful.”

In works such as Salmon on Saran, 1974, Red Currant Jelly, 1972, and Cod Fillets on Tin Foil, 1974, Pratt pushed her technical abilities to their absolute limits, mastering the ability to convey complex visual information. The Saran wrap, for instance, is actually rendered with a series of fine white or grey lines, its transparency completed by the viewer’s optical experience, in a kind of trompe l’oeil, or trick of the eye. The tinfoil on which the jars of jelly or the cod fillets sit is made up of rich greys, purples, whites, and blacks—a remarkable, almost liquid-seeming surface that, through the perceiving eye, snaps into the crisp, reflective surface of the metal foil. As Pratt says of making these works, “I had to forget what they were—I need to think about them as just shapes and volumes.”

Mary Pratt, Glassy Apples, 1994, oil on canvas, 46 x 61 cm, Beaverbrook Art Gallery, Fredericton.

Many of Pratt’s paintings had a long gestation period. Sometimes years elapsed between the photograph being taken and the painting being made. That elapsed time, the shift in focus from the immediately observed to the carefully studied, is in many ways as important a moment in Pratt’s evolution as her initial decision to paint from slides. What began as a desire to still time, to capture the fleeting moments to which she was responding with such a strong visceral feeling, became an entire way of seeing the world.

It is important to remember that photography was far from instant in the late 1960s. For Pratt, it could take weeks or more for the developed slides to be available. First the roll of film had to be used up in the camera; then the exposed roll was dropped off somewhere in St. John’s to be developed, and then, a few weeks later, picked up again. Pratt had to learn how to look at the slides as images in themselves, to see if she could remember what it was that was so striking about that picture that she felt she had to capture it.

Sometimes the image seemed as fresh as the moment Pratt saw it in real life. Others felt flat. Over Pratt’s career increasing piles of slides accumulated, waiting to be used. Most never would be, remaining in boxes in her studio storage, or discarded.

Capturing Light

“Photography stills everything, so you can look at things, and see how they work.” Struck by the light coming through the jars of jelly that her mother would put up in the kitchen, and trying to recreate the experience for herself, a young Mary Pratt would fill jars with water that she had tinted with food colouring. These would sit on her windowsill, reflecting coloured light into her room (Jelly Shelf, 1999). Pratt also revelled in the light from the stained glass windows at Wilmot United Church, which illuminated her childhood Sundays. The challenge, always, was to capture those moments touched by light. Pratt needed a way to slow time, and slides did just that.

Pratt initially resisted using photographs, finding that it felt like cheating, and that it ran counter to her training. Yet why not take advantage of such a useful tool? As painter David Hockney (b.1937) has persuasively argued, optical instruments such as the camera obscura were available even to the Old Masters, and painters have used photography-like aids as source and research materials for centuries. Still, Pratt had to deal with her work being downplayed as mere documentation—what one critic called “an earnest mirroring evolved from commercial art school exercises in product illustration.”

Pratt has indeed admitted to an interest in commercial imagery. Like so many North Americans of her generation, Pratt grew up in a city that didn’t have an art museum. (The Beaverbrook Art Gallery, Fredericton, opened in 1959, when Pratt was twenty-four, married, and living in Newfoundland.) It was through the mass media of her day—magazines in particular—that Pratt first saw painted imagery. She responded to its colour, luxury, and glossiness. There were no brush strokes evident in these works, and they had an overt sensuality to which she responded.

Pratt’s own slide-based approach allowed her to recreate this effect to her own ends, rather than commercial ones. Though Pratt felt that she had crossed some sort of line through the use of photography, her physical isolation in Salmonier and her intellectual, and self-imposed, isolation from the art world meant that she didn’t know much about Pop art, Photorealist painting, and the many ways that photographs were changing modern and contemporary art.

It is the use of photographs that gives Pratt’s work its critical edge. As art historian Gerta Moray has argued, Pratt’s painting addresses the key twentieth-century (and twenty-first-century) challenge of painting in the face of mass media: “Mary Pratt’s pictures are paintings done after the death of painting,” Moray writes. Of course, reports of painting’s death have been, to follow Mark Twain, greatly exaggerated. The use of photographs, the evocation of commercial imagery, the depiction of banal objects—all are strategies that have been followed by diverse artists, particularly by the Pop artists exemplified by Andy Warhol (1928–1987), himself a former commercial artist, and also by less easily categorized artists such as Gerhard Richter (b.1932).

“One of the things about using photography,” said Pratt, “is that I didn’t have to face the real thing—it separated me a little bit from reality and allowed me to think about them as shapes and volumes and colours. If I tried to do the real thing I’d sit and cry!”

Unlike Christopher Pratt and Alex Colville, Mary Pratt did not use the photograph as a model from which to paint. Instead, she directly translated the photograph to painting. She tried to recreate the light that the camera recorded. Equally importantly, she imitated the way that the image was captured—the focus, the depth of field—that reflected the mechanical lens of the camera rather than the human eye. Blurriness or unnatural sharpness—these things and more are depicted by Pratt as they are in the photograph. “Well, I’m working with a camera,” she said, “and that is what it has given me.”

The use of photographs as source material freed Pratt to concentrate on the subject that was dearest to her heart—things bathed in light. Pratt remembered her first physical response to light: “One time when I was a child, my mother knit me a lovely red sweater. I slung it over my chair back by my bed, and when I woke up, the sun was shining through the red sweater and I loved it. I raced home to see it again and somebody had put the sweater away. I felt robbed.” The adult Pratt turned to photography to right this wrong—that “the light wouldn’t stand still long enough for me to catch it.”

Scale

Mary Pratt’s process was so detailed that, in her oils, she tended to work on a small scale, her domestic subjects rendered at humble sizes. Many of the works in her Donna series, however, and several of the mixed-media drawings that she made throughout the late 1980s and 1990s, are exceptions.

In Pratt’s Donna series she increased the scale of her work: both Girl in My Dressing Gown, 1981, and This Is Donna, 1987, are approximately two-thirds life-size, greatly heightening the confrontational quality of the works. With Pratt’s Fires series, such as Burning the Rhododendron, 1990, she found that by using pastels and coloured chalk she was able to work at a scale far beyond anything she had attempted in oils. This change in media was driven in part by physical constraints due to old age and ill health.

The drawings began in a similar way to the paintings—projecting an image onto paper and then tracing in the outlines. Pratt worked in oil and chalk pastels and finished up with watercolour. She wrote about the process of making one of these, Big Spray at Lumsden, 1996, in her journal:

I began by establishing all the white with oil pastel—the froth and foam and spray and dots of spray, the falling shine, the light. Then I “drew” the detail with watercolour. Then I took some white chalk pastel and filled in the parts of the wave that really were blurs of foam. Next, I started again with the oil pastels to “generalize” the background sea, land and sky. I think I’ll go over that with watercolour today to tie it together and make it richer and simpler.

Pratt’s series of woodblock prints made in the Japanese ukiyo-e process in collaboration with master printer Masato Arikushi (b.1947) was her only sustained foray into the medium. The ten prints in the Transformations series, made between 1995 and 2002, were each produced in an edition of seventy-five and were based on existing works—oils or watercolours. Pratt would correct the colour of the proofs, and make drawings that showed ways of adapting the original image. It was a very different approach for her as an artist, as she began to find Arikushi’s sensibility being reflected in the works. “Gradually his own ideas melded with my original images, and I detected his own imagery inserting itself into my own. I liked that. It all fit.”

By 2013 Mary Pratt had stopped painting. Her health issues, among them arthritis, autoimmune disease, and deteriorating vision, just made it too hard. When put on antidepressants, Pratt told her doctor that under the medication’s influence she wouldn’t be able to paint. He assured that she would be able to paint better than ever. “Well, he was wrong and I was right,” she said in 2014. She found her last retrospective, which toured from 2013 to 2015, bittersweet. “I worry that it’s sort of over,” she said.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements