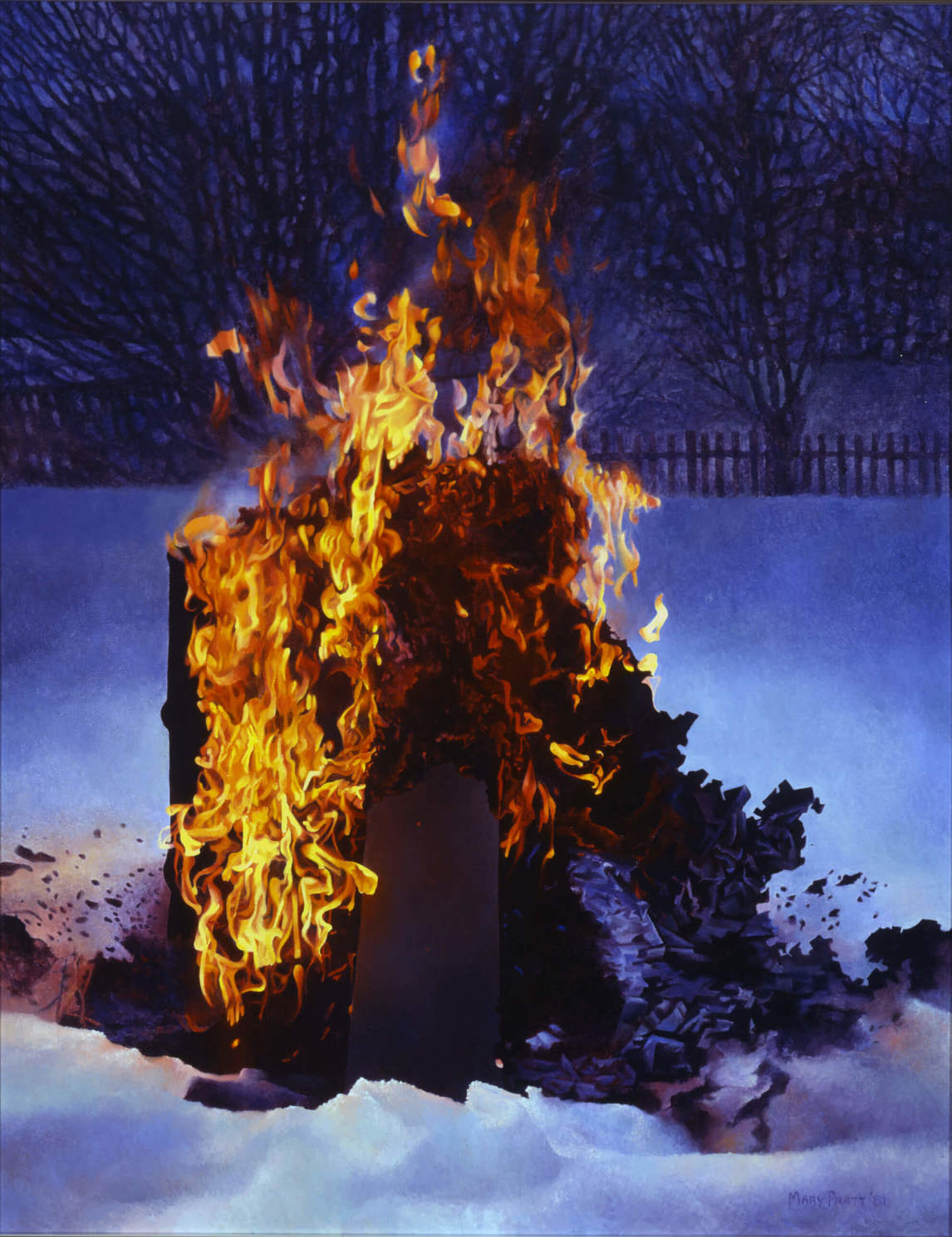

Burning the Rhododendron 1990

Mary Pratt, Burning the Rhododendron, 1990

Watercolour and pastel on paper, 127.6 x 239.4 cm

Sun Life Assurance Company, Toronto

At well over two metres wide, Burning the Rhododendron is one of Mary Pratt’s largest works. This scale was possible only because of a change in working methods: switching from oil on panel or canvas to mixed media—watercolour and chalk, or oil pastels, on paper. It was made a year after she showed a series of these fire drawings at Mira Godard Gallery, Toronto, in an exhibition called Flames.

Light had always been Mary Pratt’s chief subject, captured as it played across the surfaces of things, transforming the mundane into the sensual and erotic. We see that in the ephemeral play of light in The Bed, 1968, or on the scales of the fish in Salmon on Saran, 1974. Her series of fire works, however, is not so much about how light transforms objects, but about light itself as a beautiful destroyer. As Tom Smart writes, “In the bonfire drawings, she was able to represent light itself at the moment of its creation as it consumes matter.” Based on a photograph of the burning of a dead rhododendron bush in her back garden, this work references the biblical story of God appearing to Moses in a burning bush, and speaks directly to how light is revelatory. From the stained glass windows at her local church, through the jars of coloured water that she would leave on her windowsill, Mary Pratt’s childhood fascination with light would never leave her.

Pratt told Smart, “The fire had to be alive.” Writing about an earlier work from this series, she said, “The careless slap and dash of mixing a water-based medium with a waxy medium allowed me to make this bonfire work.” Pratt was looking not for the deliberation and the realism of so much of her oil painting, but for a more immediate effect. She wrote, “It is an image as fluting and as ephemeral as a bonfire really is.”

Pratt worked on these images with her whole body, usually while standing, and the process provided a break from her usual cramped way of working—sitting and crouching over an easel and constantly twisting to see her slide viewer. “She could stand at her easel,” Tom Smart writes, “move around, use her whole body to make marks on the paper.” She worked in this manner for several years, but eventually her ongoing health issues, particularly her arthritis, stopped her from working at such a large scale.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements