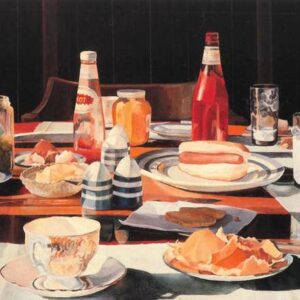

Jelly Shelf 1999

Mary Pratt, Jelly Shelf, 1999

Oil on canvas, 55.9 x 71.1 cm

Private collection

When Mary Pratt was a child in Fredericton, she was struck by the light coming through the jars of jelly that her mother had put up in the kitchen. “When my mother lined up jars of jelly on the kitchen windowsill, they blazed in the same way as the church glass [of Wilmot United Church]. When she unmoulded the jelly into a crystal dish and brought it quivering into the dining room, the colours spread and changed as they shot through the facets of the crystal. . . . It was, for me, the most beautiful thing I could look at.” Trying to recreate the experience for herself as a child, Pratt filled jars with water tinted with food colouring. She put these on her windowsill, “to keep the magic of that brilliant coloured light.”

Pratt’s 1999 painting captures this fleeting quality of sunlight through translucent jellies. In her composition, the jar sections form vertical slices, with a gap on the left looking back into the kitchen. The sense of both light and deep space keeps the viewer a little off balance. The reflective counter, shadowed by the jars, glows with deep, rich colour. In shadow, then, there is light—what critic Robin Laurence calls “a sense of blessedness.”

In talking of her early work The Bed, 1968, Pratt maintained that the light wouldn’t “stand still.” Slides helped her capture those moments, and as her practice evolved, she became adept at the difficult technique of conveying light in a painting. Here the light doesn’t stand still so much as vibrate—a liquid that seems embodied in the translucent jelly. Pratt’s teasing of light out of shadow, her use of strong bright spots amid dark areas, is part of a long tradition that stretches back at least as far as Caravaggio, in which painters challenge themselves to capture the fleeting, spiritual qualities of light.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements