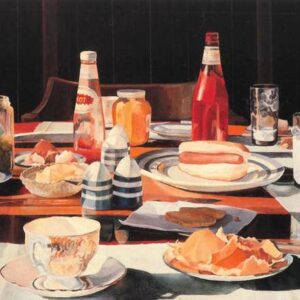

Supper Table 1969

Mary Pratt, Supper Table, 1969

Oil on canvas, 61 x 91.4 cm

Collection of the Family of Mary Pratt

In 1969 Mary Pratt was struck by an experience that she would later call one of her “epiphanies.” This collection of condiments, uneaten hot dogs, teacups, glasses of milk, and orange peels may not seem a likely subject for a painting, but Pratt saw something in it. The light fleeting moment offered her inspiration and a direction she had not considered. She rushed to obtain drawing materials to capture the effect of light on these remains of a family dinner.

As Sandra Gwyn recounts, “Christopher told her she was crazy. The light would be gone before she even got her paints out. She persisted, and started making a drawing. Christopher watched her, said nothing, left the room and came back with his camera. He took quick shots of the now fading light, shining onto the remnants of supper on the table. A month or so later he brought her the slides.”

For Mary, those slides were a revelation, equal to an earlier realization that she wanted to paint the “erotic charge” she occasionally felt from light on familiar, domestic objects: “I could see so many things that I hadn’t seen before, all kinds of lights and shadows, and how a ketchup bottle hasn’t just got an outside, but an inside, too.” Pratt would now paint from photographs, despite her initial misgiving that by doing so she was “cheating.”

Supper Table is painted more crisply than The Bed, 1968, but it lacks the precision of Pratt’s later work. Its composition is different, too. By having the slide to work from, rather than sketches and her memory of a feeling, Pratt found herself recreating not an impression, but the actual photographic image. The cap to the ketchup bottle, for instance, sits at one end of the table; the bottle itself is at the other end. The crumpled orange peels are reproduced just as they appear in the photograph, not edited out or simplified in the painting process.

In The Bed Pratt had found what would be her lifelong theme: moments when the quiet, ordinary trappings of life become freighted with meaning. Now, with photography, specifically through the use of slides, she had found a tool that would inform her technique and allow her to capture these moments.

In Supper Table we see Mary Pratt’s style becoming Photorealist, a type of painting that mimics the precision and composition of lens-based images, and is often directly based on them. Tom Smart identifies Supper Table as the point at which Pratt “forcefully” adopts this genre, and “the immediate environment of her house in Salmonier” as her subject matter. It is also part of a long tradition of Western art-historical still-life painting—specifically evoking Chardin and Vermeer—in which the subject matter is the simple domestic fare of daily life. Pratt would return to this theme throughout her career.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements