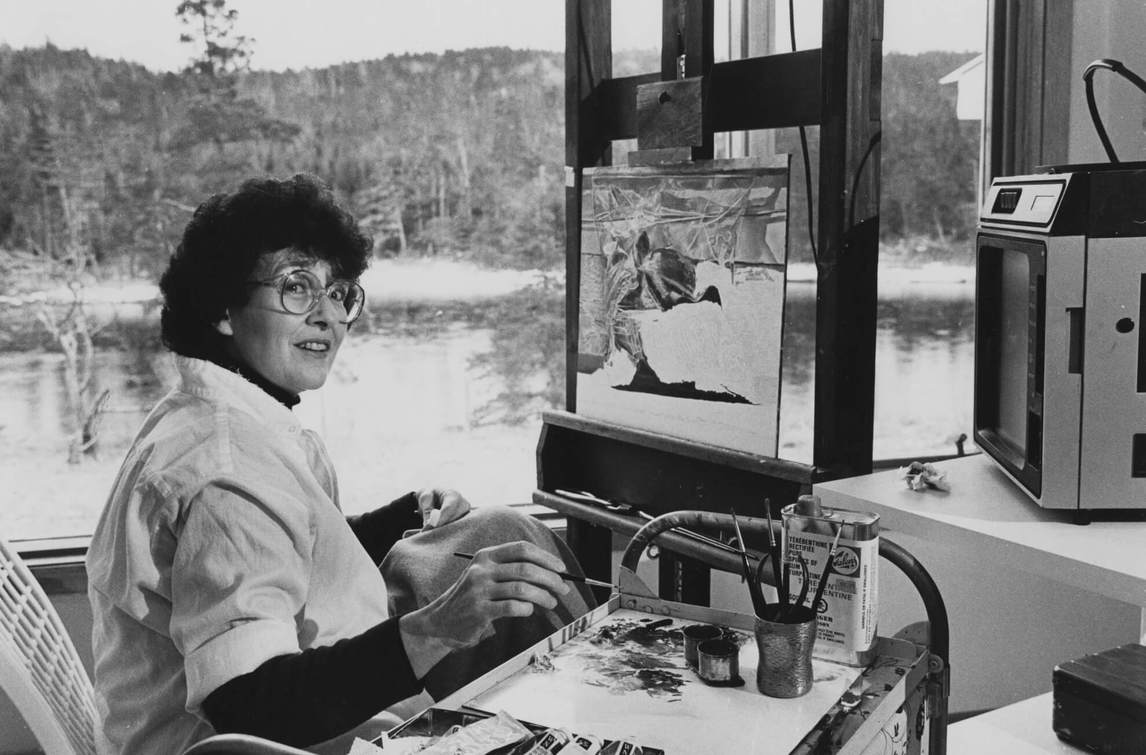

Mary Pratt (1935–2018) is an essential, beloved figure in Canadian art. Her paintings invest mostly domestic subjects with near photographic detail and compelling, often dark complexity. A professional artist for over fifty years, Pratt was born in New Brunswick but was based in Newfoundland for most of her career. Pratt’s work first came to national prominence in the mid-1970s, after years of isolation and struggle. She eventually became an iconic Canadian artist in her own right, despite the public’s tendency to compare her work with that of her former husband, Christopher Pratt. When Mary Pratt died in St. John’s, Newfoundland, in 2018, friend and former governor general of Canada Adrienne Clarkson called her “our greatest female painter since Emily Carr.”

Upbringing and Early Years

Mary Pratt was born Mary Frances West in Fredericton, New Brunswick, on March 15, 1935, to a family that belonged to that small city’s conservative establishment. Her father, William J. West, was a veteran of the First World War, a lawyer and politician who became New Brunswick’s attorney general and later a judge. Her mother, Katherine, was the daughter of a well-known Fredericton businesswoman, Kate McMurray. William was much older than Katherine; they had met while she was working as a stenographer at his law firm, when she was twenty-three and he was forty-one. The Wests were religious—active in their local church, Wilmot United. They welcomed another daughter, Barbara, in 1938.

William and Katherine were creative people, finding diversion in artistic pursuits. Katherine’s hobby was hand-painting photographs, an activity that fascinated both Mary and Barbara. The girls were enlisted to help as they grew older. Pratt remembered her mother explaining the use of colour: “She would say, ‘Now look at that grass. This is the colour you think grass is,’ holding up a tube of green pigment, ‘but if you look down in the garden do you see this colour? No. What you see is lines of pink, lines of yellow.’ I moved into doing it, just because my mother enjoyed it.”

In the conservative world of the Wests, certain kinds of artmaking were seen as appropriate accomplishments for young women. Pratt remembered that she “was no prodigy”: “When I got to be about nine, my parents realized that I was unhappy. I was fat, I didn’t know what to do with my hair, I couldn’t do math. . . . I was truly miserable, and they were, ‘Well, we’ll get her a decent set of paints.’ They bought me jars of poster paints, and they were wonderful.”

Pratt was encouraged to study drawing and painting, attending classes at the University of New Brunswick Art Centre with teachers such as Lucy Jarvis (1896–1985), Fritz Brandtner (1896–1969), and Alfred Pinsky (1921–1999), as well as taking private lessons from John Todd, a graphic artist who had been trained in New York at the Pratt Institute. Mary was a precocious student, once winning inclusion in an international exhibition of children’s art held in Paris. At ages sixteen and seventeen she went to Todd’s studio for lessons every Friday evening, an important moment in her development as the instruction concentrated on the commercial aspects of artmaking, on design, and, in particular, on photography. Tom Smart, director and CEO of the Beaverbrook Art Gallery and curator of the 1995 touring exhibition The Art of Mary Pratt: The Substance of Light, notes in the accompanying catalogue that “Todd urged her to keep a file of photographs, clipped from weekly new magazines, as a source of images for her art.”

Pratt remembered her childhood in Fredericton as idyllic. In many ways, it set the pattern for her future life. Her father was a veteran of the First World War’s trench warfare, and was determined to build an insulated and tranquil home. She recalled that despite her father’s professional prominence the family kept a lot to themselves: “We were always outside, always. I felt the otherness of us in Fredericton.” Her mother came from a long line of women who, as Pratt described, “had to go it alone, who had to take life and fight for it.” Like her father, Pratt’s mother also wanted their home on Waterloo Row, the most prestigious address in Fredericton (then and now), to be a haven, albeit one ordered inside and out.

In an address given at Wilmot United Church in 1999, Pratt recalled: “I spent my life in a small part of Fredericton. Partly because of the polio”—as with many Canadians of her generation, the polio epidemic was a fact of Pratt’s childhood—“partly because of protective parents who believed that little girls benefited from a simple life lived in a garden, a kitchen, a school, and a church.”

That simple life, with her parents and her younger sister, Barbara, gave Mary Pratt safety and protection, and turned her imagination inward. It also fostered a self-confidence that never left her. Privileged to have grown up loved, Pratt knew that she had potential as well as responsibilities. One of these responsibilities was an education. Though she had decided to study art at a young age, she had a change of heart at eighteen, telling her father that being an artist was “too selfish.” His counterargument, as Pratt told the art critic and curator Robin Laurence, was that it would be selfish of her not to be an artist. “You have a talent and it is a requirement of you to paint,” he said. “It is your fate—you’re going to have to study art.” And there was never any doubt where that study would take place: her father’s alma mater, Mount Allison University in Sackville, New Brunswick.

Mount Allison University

Eighteen-year-old Mary West began her studies at Mount Allison in 1953, at the School of Fine and Applied Arts. What she discovered was a small, conservative university, still true to its Methodist roots. In the arts, the focus was on strong practical fundamentals. Two of the faculty members were realist painters: Ted Pulford (1914–1994) and Alex Colville (1920–2013). The third, Lawren P. Harris (1910–1994), son of Lawren Harris (1885–1970), a founder of the Group of Seven, had been a realist, but by the 1950s was becoming an abstract painter. Tom Smart writes, “The department’s reputation was based on an approach that taught technique almost exclusively.” This must have suited Pratt, who had long held that she was not “artsy,” and claimed to have never looked to the larger art world for inspiration or validation. “The world of art escapes me,” she said in 2014. “The world of life does not.”

Painting in the 1950s was undergoing one of its periodic convulsions. In Canada, the serious painters who represented what was most critically valued worked in an abstract mode: Jean Paul Riopelle (1923–2002), Jack Bush (1909–1977), Harold Town (1924–1990), William Ronald (1926–1998), and Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960), in particular. In the United States the painter of the moment was Jackson Pollock (1912–1956), at the head of a virtual flood of Abstract Expressionists. Entering art school, Pratt worried she was wasting her time, but she was fortunate to be in a milieu in which a certain kind of realism—known loosely as Atlantic Realism—was embraced and practised by her successful teachers. When Colville asked her what she was hoping for from the program, Pratt told him she was “terrified I might turn out to be a Sunday painter.” Colville did not hesitate in his response, she remembered: “You won’t be.” Colville was stating his faith in the demanding Mount Allison program, “a regimen of instruction that was guaranteed to bury amateurism in professional rigour.”

The program of study that Pratt followed was primarily intended to serve students who were seeking to become commercial artists, industrial designers, or teachers. Accordingly, it was based on a program of gradual and incremental approaches to artmaking—learning the fundamentals first, and only then experimenting. In a four-year program, Pratt and her peers spent three years on the basics of design and drawing, with courses in sculpture (modelling in clay from figurative sources), and painting and drawing from still-life arrangements. This included art history, giving students a grounding in the story of Western art, up to and including modernism. Here Pratt learned of artists who would come to be an influence on her, notably the Dutch masters, especially Rembrandt. In the fourth year of studies, students were given a less structured environment to pursue more independent directions. For the remainder of her career, however, Pratt would work primarily in the still-life genre in which she was immersed at Mount Allison.

Christopher Pratt and the Move to Newfoundland

It was at university that Mary began what was one of the most important relationships of her life, when she met a young pre-med student from Newfoundland named Christopher Pratt (b.1935). “The fascination with Christopher lay almost entirely with his mind,” she wrote—“that part of his thinking that concerned images and ideas.”

While Christopher had painted as a youth, he had been pressured by his family to study something practical. Christopher’s father wanted him to take over the family’s wholesale hardware business. At first, Christopher had considered engineering, taking preparatory courses at Newfoundland’s Memorial University in 1952. In 1953 he moved to Mount Allison, registering in pre-med classes but ultimately taking only humanities courses, including art. Despite his parents’ objections, Christopher became determined to be a painter.

Mary and Christopher knew each other from 1953, and began dating in early 1955. Mary graduated with a fine-arts certificate in 1956, qualifying her to be an art teacher or occupational therapist—what we would now call an art therapist. That fall she moved to St. John’s, Newfoundland, to work as an occupational therapist, and to be near Christopher, who had quit his pre-med program at Mount Allison and moved back home to concentrate on painting.

In September 1957 Mary and Christopher married. Shortly after their wedding at Wilmot United they sailed for Scotland: Christopher had decided to continue his studies abroad and was accepted into the Glasgow School of Art. Once settled, Mary attempted to enrol in the fine-arts programs to take some classes but was refused admittance, as she was pregnant and the head of school did not want her attending in her “condition.” (The systematic exclusion of pregnant women from professional life was common in the 1950s.) The Pratts returned to St. John’s in July 1958 for the birth of their son John. Mary moved on to Fredericton for the summer while Christopher remained in St. John’s. At the end of the summer, the family reunited and returned to Glasgow.

In 1959 the Pratts returned to Mount Allison, where Christopher completed his third-year studies in art, and Mary arranged to resume her studies toward a bachelor of fine arts, spreading the required courses over two years. Their elder daughter, Anne, was born in 1960. Near the end of Mary’s program one of her professors, Lawren P. Harris, gave her advice that has become famous in her story: “Now you have to understand in a family of painters, there can only be one painter, and in your family, it’s Christopher.” The advice may not have been meant as cruelly as it sounds today, and Mary herself maintained that she was eventually grateful for it, speculating that Harris was trying to save her from marital strife. Nevertheless it stung, and it speaks damningly to the discrimination against women painters during this time.

Mary took Harris’s advice as a challenge, and rose to it. Robin Laurence writes, “Harris’s words triggered Mary’s fierce contrariness, forging her resolve to carry on painting.” Mary has told the story many times over the years, with all the slight variations one would expect. One thing remains constant: Harris’s words confirmed her will to paint. “I’ve always felt that of all the things I learned at art school, that moment was probably the most important,” she said. Both Mary and Christopher graduated from Mount Allison in 1961, after which they returned to St. John’s to live. Christopher took a job as curator of Memorial University’s art gallery.

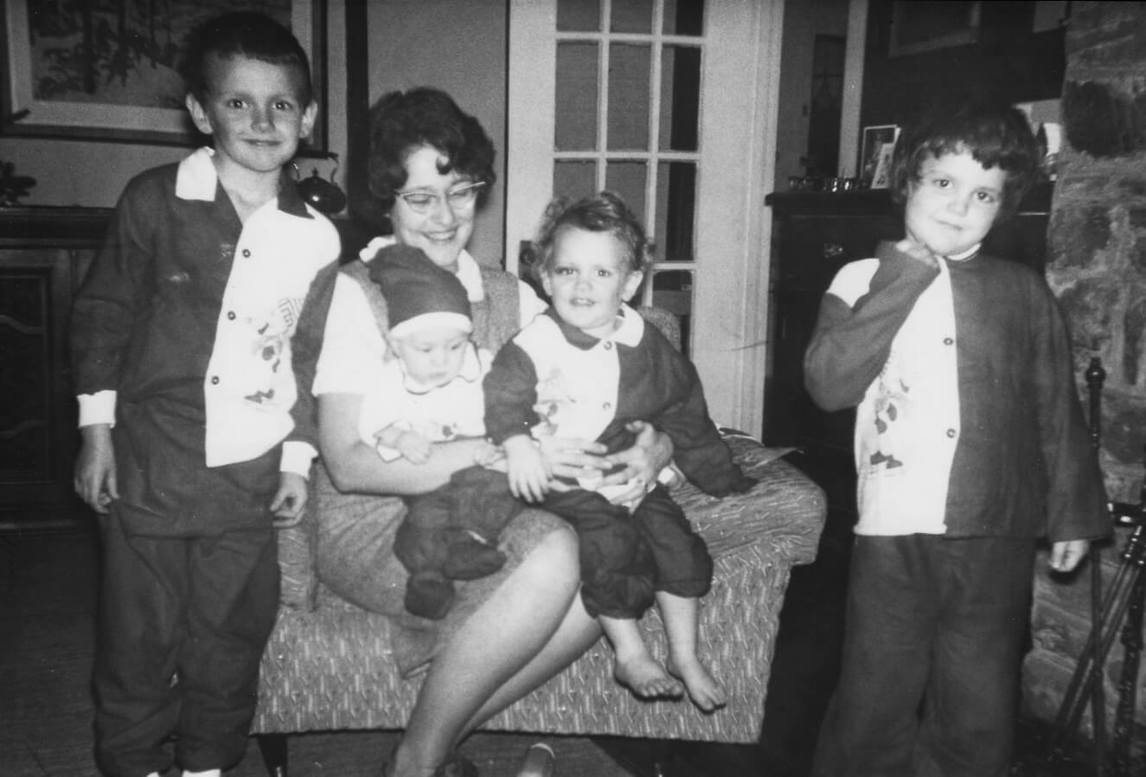

During those first years in Newfoundland, Mary was able to work as an artist, teaching art two nights a week for Memorial’s extension services. She was included in a group exhibition at the Dalhousie University Art Gallery, Halifax. The demands of a growing family pressed, of course, cutting into the little time she had to work at painting. In early 1963 the Pratts’ third child, Barbara (Barby), was born.

Also that year, Alex Colville decided to quit teaching at Mount Allison in order to pursue his painting career full-time. The university made clear to Christopher that Colville’s job was his if he wanted it. At the same time, Christopher’s father offered them the rent-free use of a cottage he owned in the small village of St. Mary’s, near the somewhat larger village of Mount Carmel and on the banks of the Salmonier River, a little over an hour’s drive from St. John’s. While Mary never explicitly said that she hoped Christopher would take the job at Mount Allison, they both knew it was her preference. Instead, Christopher opted for Newfoundland—for painting full-time (he had also decided to resign from Memorial), and for the cottage.

The move to Salmonier may have suited Christopher, but it became like an exile for Mary. The cottage, intended as a seasonal fishing lodge, was not winterized, nor did it have running water. Mary remembered: “You could drop dimes through the floorboards. . . . In the winter, when I was pregnant, I had to break the ice to get water from the brook.” She described the conditions to Robin Laurence as “medieval.” “The first years were so hard, it hurts me to think of them,” she told Sandra Gwyn. University educated, Protestant, come-from-away, a non-drinker (and so never seen in the local beer parlour or at the dances), and living in a cottage once owned by a well-off St. John’s family (the “Murray place”), Pratt stood out in the poor, rural, and Roman Catholic St. Mary’s of the late 1950s. “I felt that I’d been cut off from my childhood and from everything I’d ever known,” she said in 1989.

In addition to caring for the children, Mary was, initially, also caring for Christopher, whose resignation from Memorial was accompanied by stress-related health issues, including stomach problems and recurring panic attacks, which he attributed to teaching and anxiety about his art career. It was hoped that, with the small cottage, they could now live on Christopher’s modest, but growing, income as an artist. In 1964 the Pratts’ fourth child, Edwyn (Ned), was born.

Settling into their rural life, and freed from the constraints of Memorial, Christopher flourished artistically, but Mary struggled. She continued to paint, but as Christopher’s career grew, hers stalled. He had a studio, for instance, where he worked full-time. After breakfast he went there to work, and would emerge for lunch, then go back for the afternoon, staying until it was time for dinner. Mary’s job, however, was first and foremost her children and the house.

Nonetheless, Mary stole time to paint, working on a small easel, moving it from room to room, and tucking it away out of sight (and far from small fingers) when she was not painting. Christopher was gaining a national reputation, with multiple inclusions in National Gallery Biennials, solo shows in Vancouver, Montreal, Edmonton, and Kingston, and a burgeoning commercial career, including gallery representation in both Toronto and Montreal. Many visitors made their way to the house to see Christopher’s work and to meet his family. As Sandra Gwyn remembers, most of them viewed Mary as a housewife: “Visitors to Salmonier, including Richard and me, raved about her homemade bread and said the right things about her flower garden and her children. Nobody thought to ask her about her paintings, because nobody knew there were any.” Mary remembered that she “was furious that Christopher had somehow got it all together and that somehow, I’d lost it.”

What Can You Be?

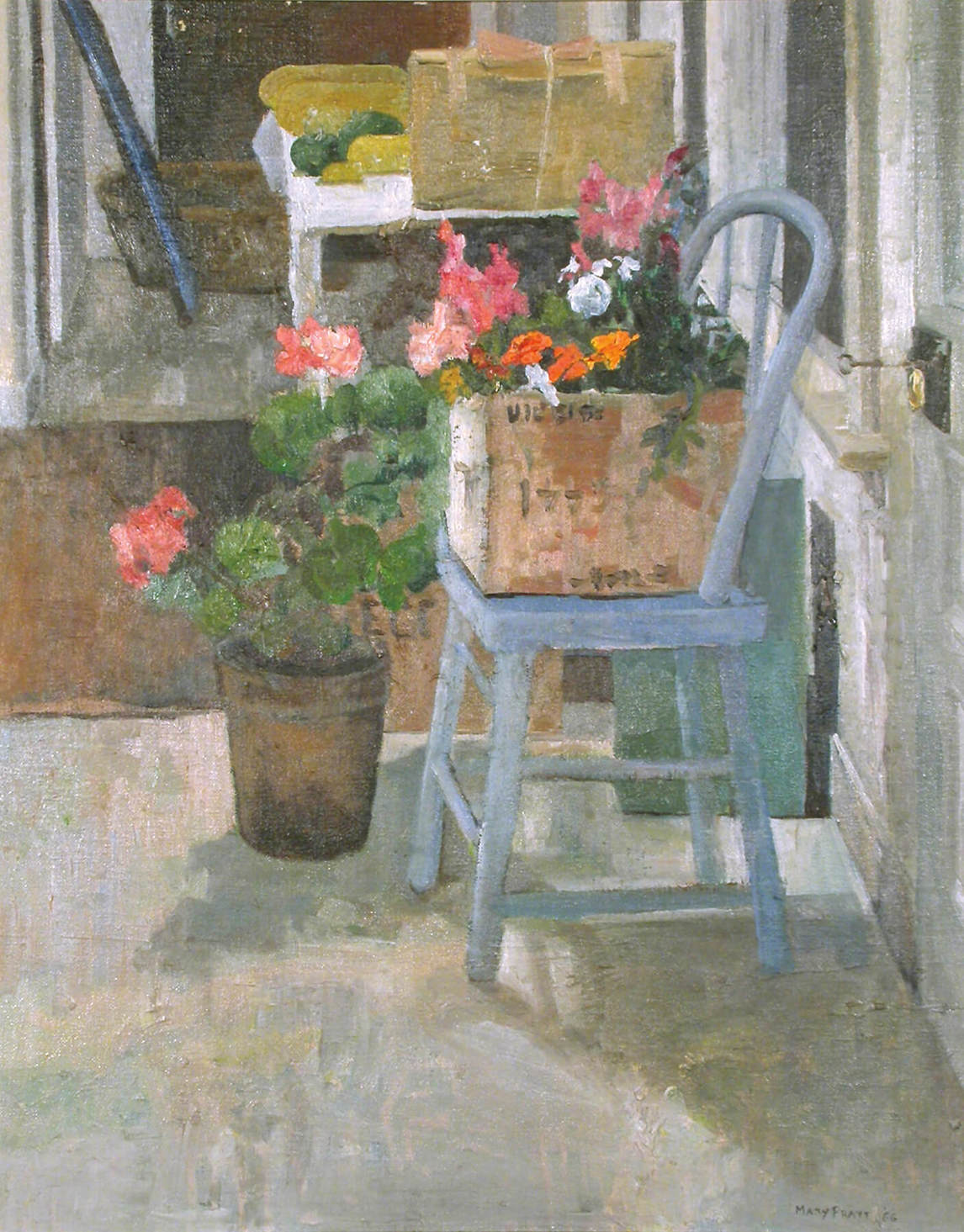

One person who did know there were paintings to see was Peter Bell, who had succeeded Christopher as Memorial’s art-gallery curator. In 1967 he offered Mary a show, and she exhibited forty-four works—drawings and paintings—in an exhibition that almost sold out. (Small public galleries in those days often served as commercial venues for exhibiting artists.) But for Mary, her pieces still felt preparatory, and despite the success of her exhibition she was unsettled in her work, seeking some different direction.

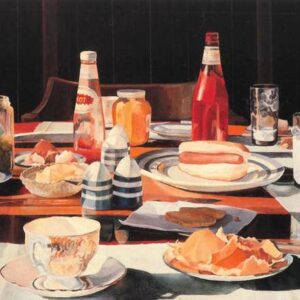

At that time Pratt was painting in a manner that she described as “impressionistic,” with loose brush strokes much influenced by the noted Montreal painter Goodridge Roberts (1904–1974), who had roots in Fredericton and had been an artist-in-residence at the University of New Brunswick Art Centre, Fredericton, though Mary had never met him there. Her paint handling was, she believed, “ugly and messy,” and she wanted to smooth out the surfaces, to rein them in. Then came the dual epiphanies of an unmade bed and a cluttered supper table.

In two paintings dating from 1968 and 1969 (The Bed and Supper Table, respectively) Pratt found an approach to her brushwork and to the use of photography in which her subject and her process coalesced, sparking a remarkable burst of creativity that fuelled her painting for decades. The first epiphany was the recognition that her subject was light, and the “erotic charge,” to use her words, that she felt from engaging with it. The second was the use of photography, which Christopher encouraged—it was he who took the source images for Supper Table, while Mary had remained determined to draw her subject. Photography would free Mary to capture light uniquely, in her own time. She realized “what the nature of her painting project had to be, capturing not only the way light transformed the domestic moment, but her own physical response to it.”

Initially for Pratt, using photographs as source material was difficult, even shameful, despite her early training with John Todd; Mount Allison had taught her that direct observation of life was the proper way to paint. Even her parents, who had always been supportive, disapproved: “They were very upset that I was working from photographs,” she remembered. “They thought it was immoral. They thought that I was cheating.” Poised on the brink of fully realizing herself as an artist, Pratt had a crisis of confidence and pulled back. For a period in 1970, she quit making art altogether, leaving the painting Eviscerated Chickens, 1971, unfinished on her easel and taking sewing lessons instead.

Her family and friends encouraged her to go back to painting. Christopher wrote Mary a note, enclosing in the envelope her painting’s source slides. (Both Christopher and Mary worked from slides—developed photographs printed on transparent bases and mounted in plastic or cardboard frames, which were then placed in a circular tray called a slide carousel in order to be projected.) “Please finish this picture, because if you don’t, I foresee a long future of taking flowers to the mental hospital on Sunday afternoons,” Christopher wrote. In the end, it was Mary’s then-seven-year-old daughter Barby who tipped the balance, asking, “Mummy, if you’re not a painter, what can you be?” The question brought Mary up short: “I thought, ‘Oh my God, I can’t let the girls down. They can’t see me falter now. What will they do when they themselves grow up?’” So, with her typical fortitude, Pratt returned to painting.

Visitors still trooped to Salmonier to see Christopher’s work, but more and more of them were seeing Mary’s as well. Mayo Graham, curator of the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, while on a visit with a colleague to see Christopher, saw Mary’s Cod Fillets on Tin Foil, 1974, on an easel in a side bedroom of the house and asked about it. Pratt remembered that she did not place much importance on the conversation that stemmed from an accidental studio visit, but it led to her inclusion in her first major exhibition: Some Canadian Women Artists, a show curated by Graham for the National Gallery of Canada to mark International Women’s Year in 1975. One of Mary’s paintings from that exhibition, Red Currant Jelly, 1972, was purchased by the National Gallery in 1976.

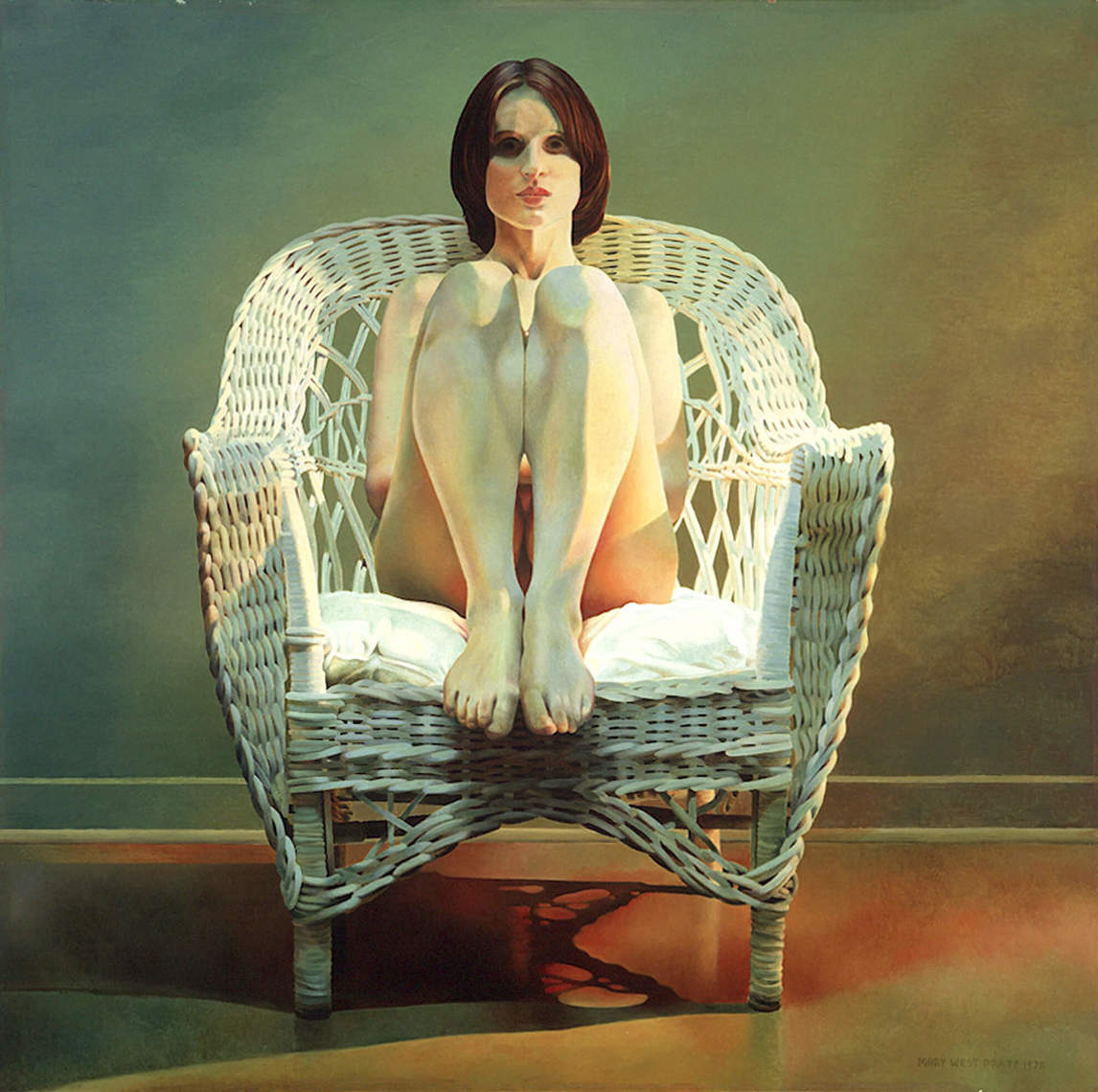

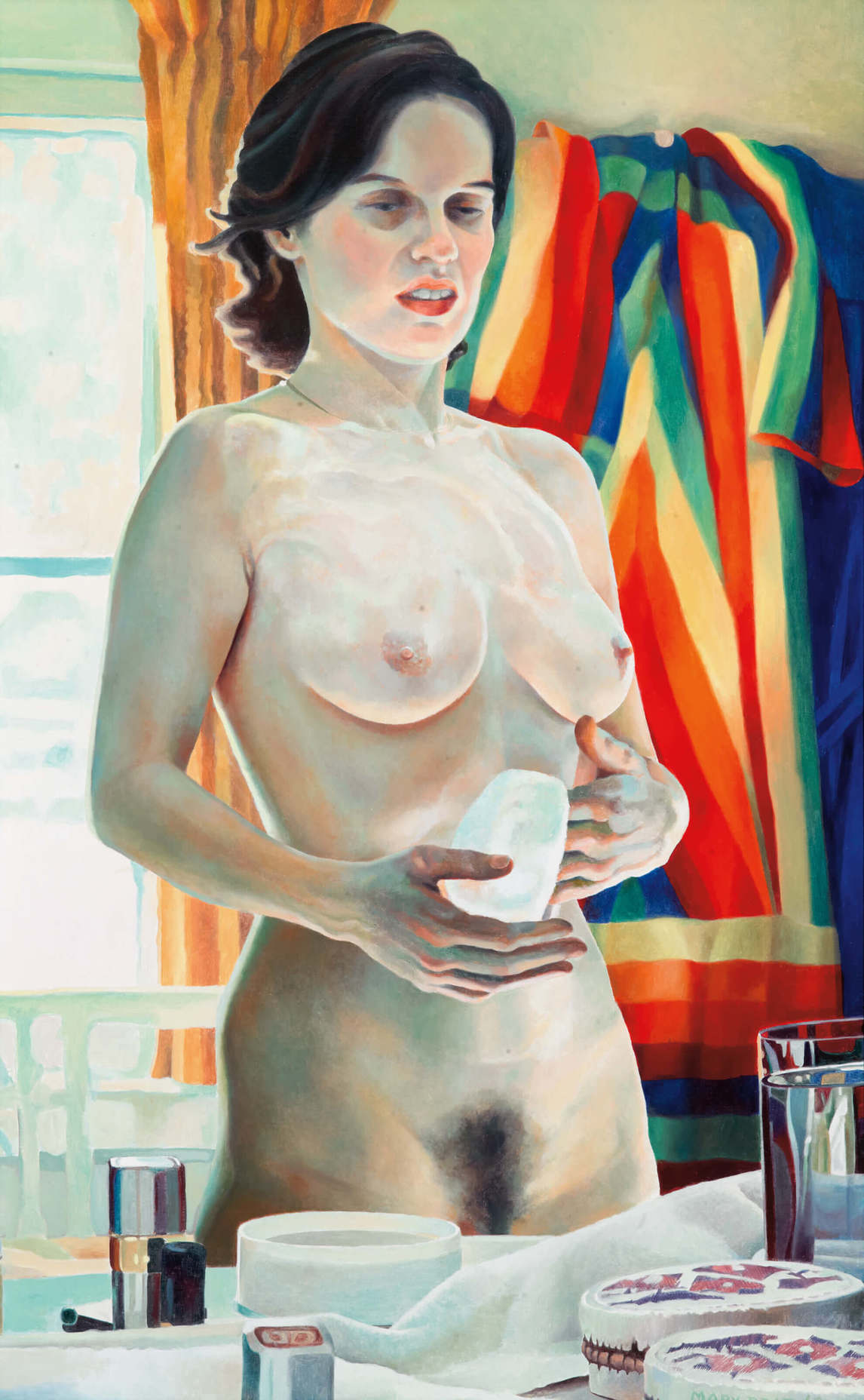

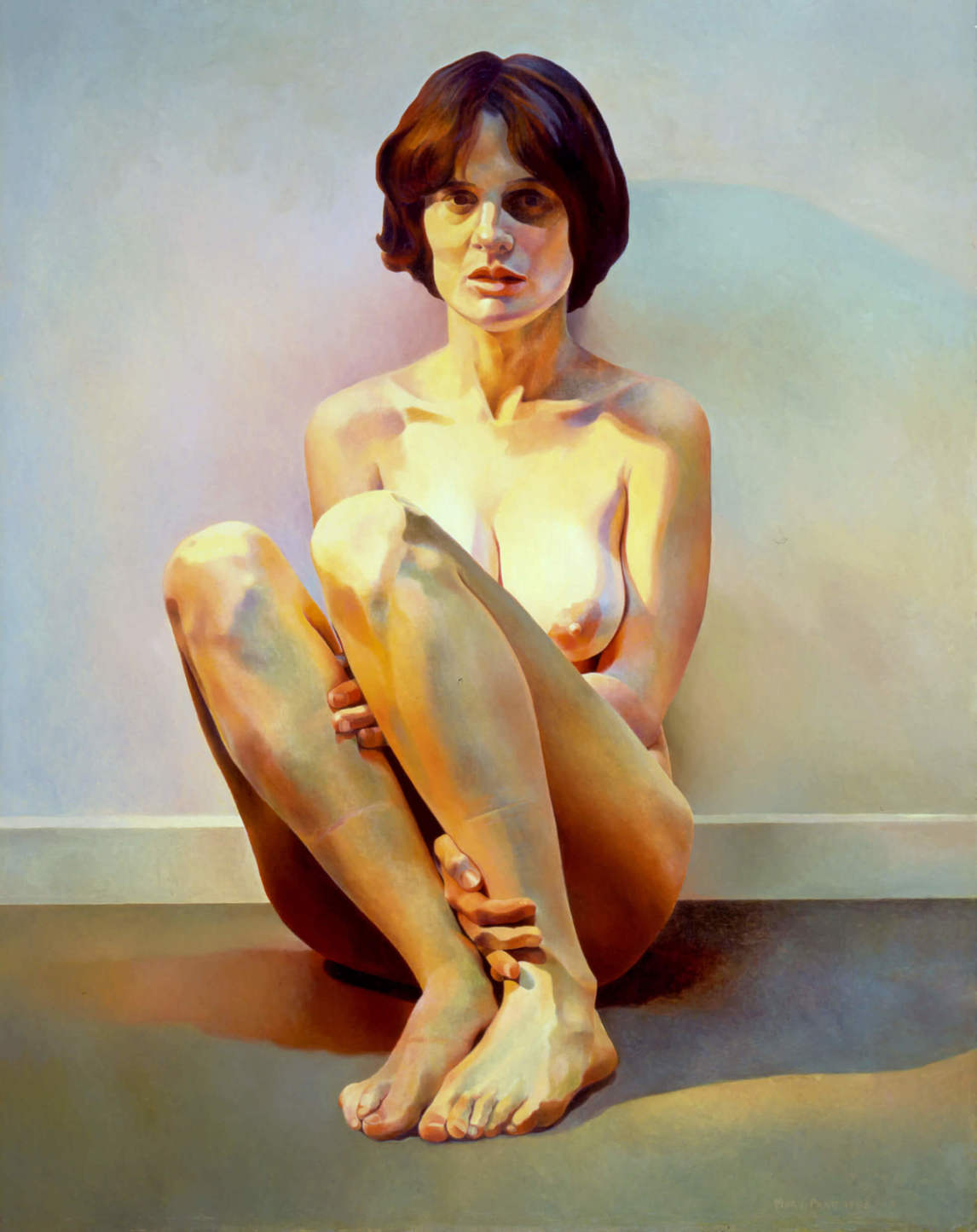

Donna

In 1978 Pratt’s painting of the same year, Girl in Wicker Chair, was featured on the cover of Saturday Night magazine—not without controversy, as many readers found the image of a seemingly nude young woman shocking. This was the first in a long series of paintings of Donna Meaney, a teenager whom the Pratts had hired as a nanny and housekeeper when she was sixteen, and who would later return as an adult. She was Christopher’s model first, and many of Mary’s paintings of her were from slides he took years before.

Christopher eventually started a sexual relationship with Donna, although neither has ever said exactly when this began. As recounted by Carol Bishop-Gwyn in her 2019 book, Art and Rivalry: The Marriage of Mary and Christopher Pratt, the relationship was full-blown by 1971, when Donna was nineteen, and she and Christopher toured around Newfoundland in a VW camper van. Bishop-Gwyn describes the couple avoiding restaurants, in order to escape scrutiny, with Christopher doing the cooking: “Through the mostly warm days of August, they happily drove, hiked, and made love.”

Mary continued to revisit Donna as a model, both in paintings drawn from photographs taken by Christopher, and in images she had taken herself. This may have been a way of dealing with the relationship between Christopher and Donna, perhaps to show she was rising above it, or maybe to allay any rumours. Whatever the reason, the paintings were a success. The contrast between the photographs taken by Christopher, where the subject is looking at her lover (This Is Donna of 1987 for example), and those by Mary, in which the model seems almost unaware of the photographer, despite being caught up in what can only have seemed to be a betrayal, such as Donna with Powder Puff, 1986, are striking. Mary’s figures are somehow more alive than Christopher’s, freighted with unspoken tension. Was Mary working out her feelings in these works? She never said one way or the other. “It’s not what you see,” Mary told Sandra Gwyn, “it’s what you find.” Pratt said that, with the Donna paintings, she was “coming as close as I ever care to come to making statements about my own situation.”

Despite the affair, Pratt always maintained that Donna Meaney was a friend, even part of the family. She told a newspaper in 2014: “I’ve always enjoyed Donna. She always makes my Christmas cake. Her daughter is like a granddaughter. Her relationship with Christopher is not the same. Whatever happened between them is their business.”

Independence and Popularity

Despite the tensions at home, Mary continued her family tradition of public service, somehow finding time amid her domestic and studio duties to serve on the province of Newfoundland’s task force on education, and, briefly, the Fishery Industry Advisory Board. In 1980, Pratt was appointed a lay “bencher,” a member of the governance board for the Law Society of Newfoundland and Labrador, and a few years later she joined the board of directors of the Grace Hospital in St. John’s. She was also a member of Canada’s Federal Cultural Policy Review Committee, although she found the experience to be less important than she had hoped. The pattern was set, however, and from then on until the state of her health precluded public service, Mary Pratt was a dedicated volunteer for many organizations. Perhaps her biggest legacy was as a driving force behind the creation of Newfoundland’s iconic culture centre, The Rooms, in St. John’s.

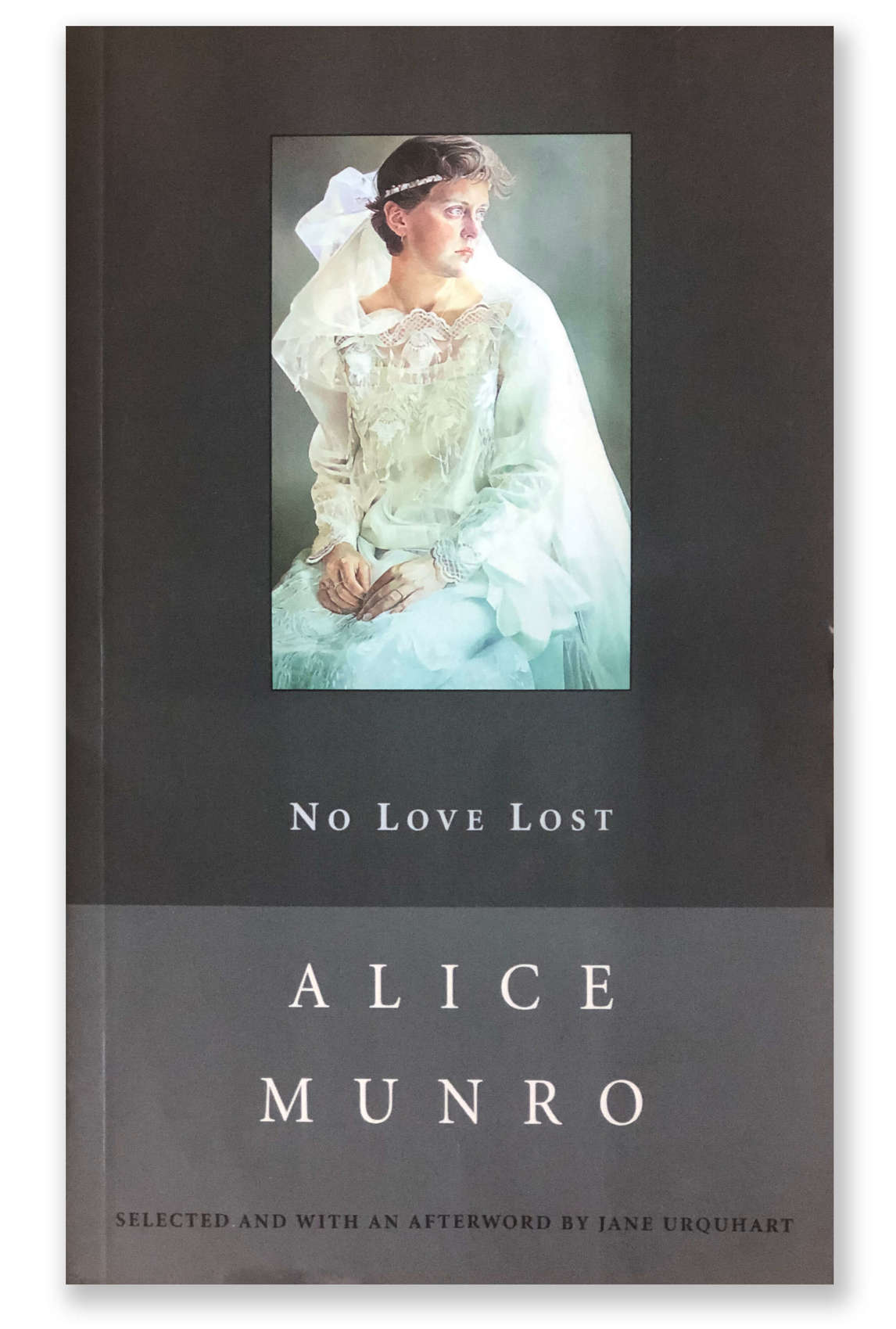

Mary Pratt continued to expand her subject matter throughout the 1980s. That decade she witnessed her children growing up and moving out of the house. Echoing the changes in her life, she painted a series of works about weddings, including a poignant portrait of her daughter Barbara, Barby in the Dress She Made Herself, 1986. The wedding paintings were all included in an exhibition at her Vancouver dealer, Equinox Gallery, in 1986. Two of the works from this exhibition were used as covers for books by Alice Munro: Wedding Dress, 1986, for Friend of My Youth, and Barby in the Dress She Made Herself for No Love Lost.

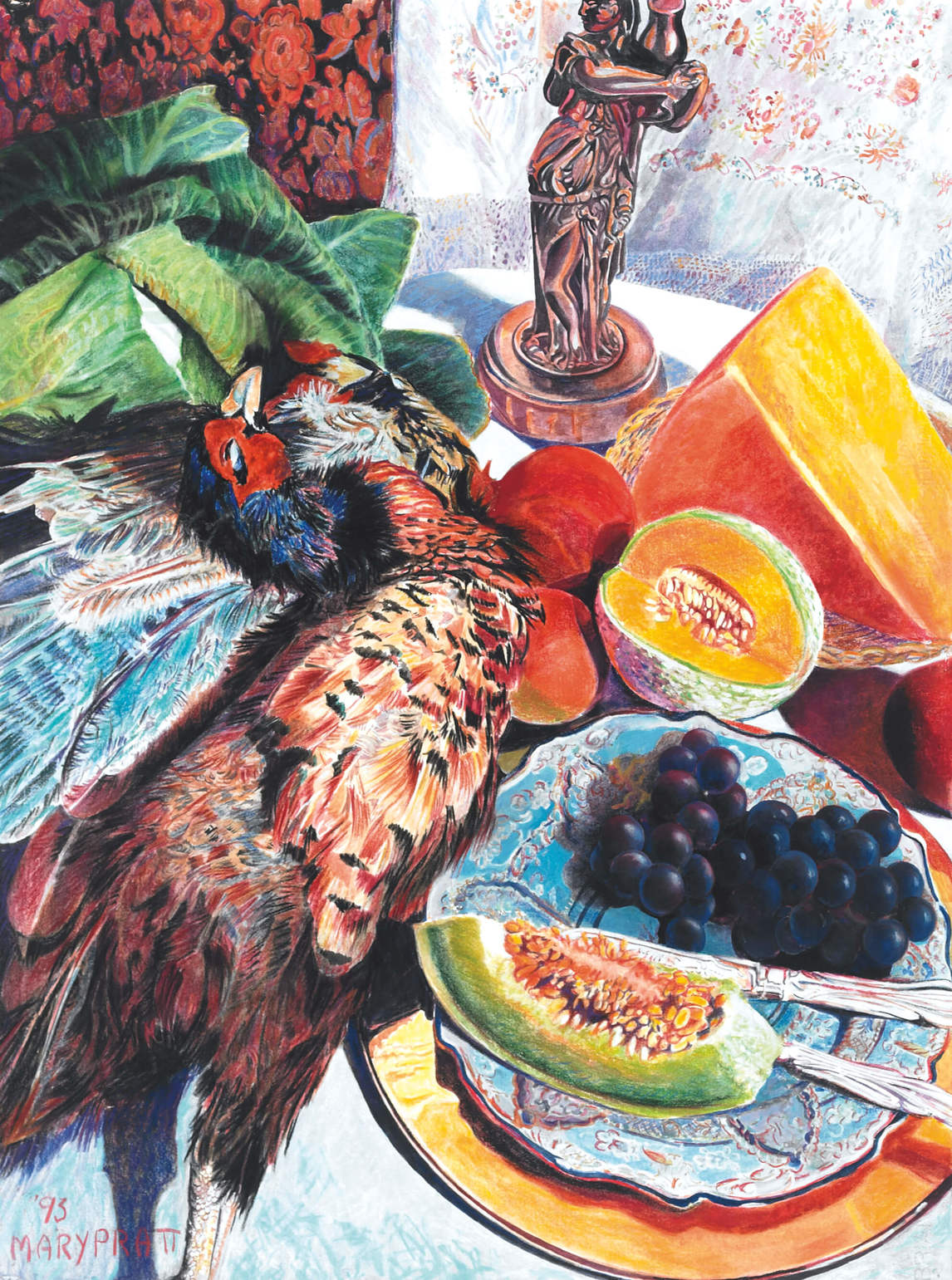

Another series of paintings and mixed-media drawings of fires, including Burning the Rhododendron, 1990, Bonfire with Beggar Bush, 1989, and Bonfire by the River, 1998, were overtly about sacrifice. By using pastels and coloured chalk, Pratt was able to work at a scale far beyond anything she had attempted in oils. She was also responding to personal physical constraints: her years of peering intently at a canvas and working with tiny sable brushes had exacerbated her arthritis and damaged her vision, and she was finding it increasingly difficult to paint. The process of making the drawings was somewhat easier on her body, and she embraced the creative possibilities they offered. Not that she was taking it easy—she was working on a large scale, stapling the paper to a board in her studio and working on the higher parts while standing on a small stepstool. As much as she enjoyed the new-found freedom of mixed media, she never stopped painting in oils; her drawings and watercolours were respites, a change being as good as a rest. But she depended on selling paintings for a living, so she painted.

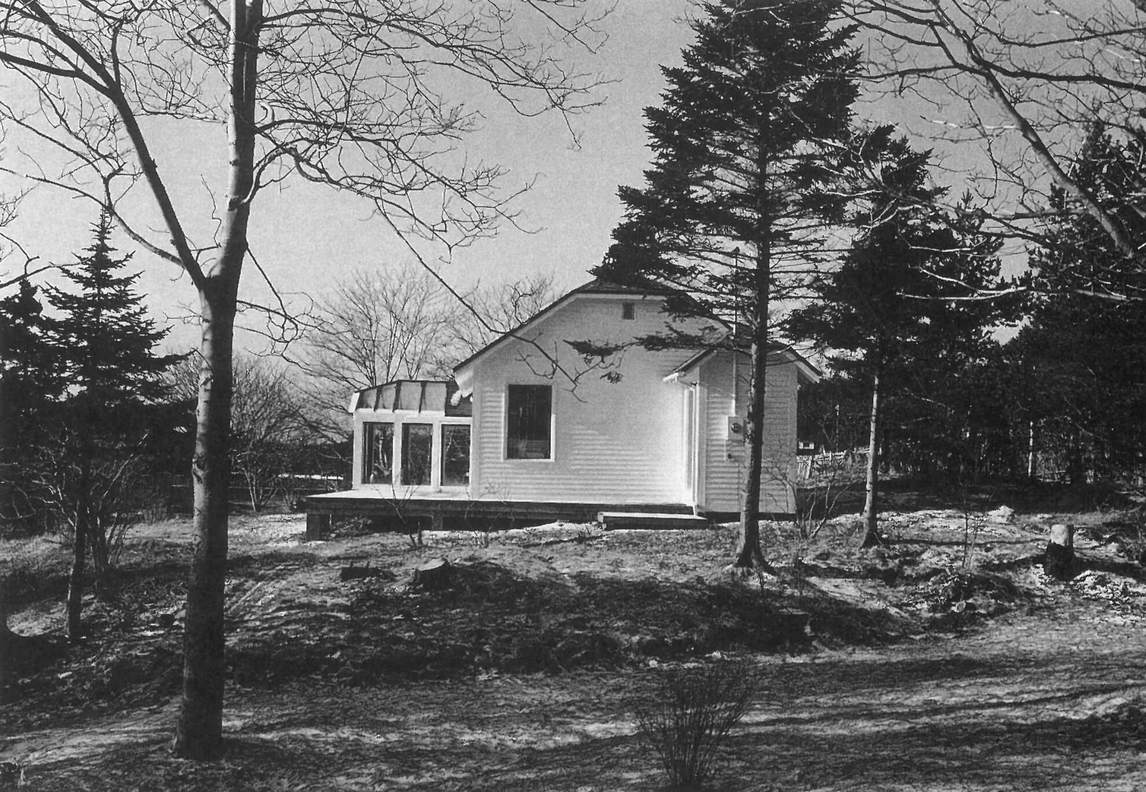

It was in the 1990s that the long-simmering tensions in Mary’s marriage came to a head, and she and Christopher separated. “It wasn’t Donna that broke us up,” said Mary, quelling rumours, “it was the girl Christopher married.” He continued to live in the house in Salmonier, while she lived briefly in Vancouver and Toronto, before building a house and studio for herself in St. John’s (a house designed by her brother-in-law, architect Philip Pratt). The couple remained separated for twelve years before divorcing in 2004.

In the paintings that she made at the time of the separation, one can sense a reassessment and a certain amount of anger. Pomegranates in Glass on Glass, 1993, depicts the fruit torn apart, spilling across the glass surfaces. In an interview years later, Pratt attributed that anger to her feelings about the divorce. Similar feelings are expressed in Dinner for One, 1994, which is reminiscent of Supper Table, 1969, the painting that marked Pratt’s first use of slides as source material and was pivotal in her development as a painter. The former work depicted the chaotic aftermath of a family dinner, the latter a neat, solo meal.

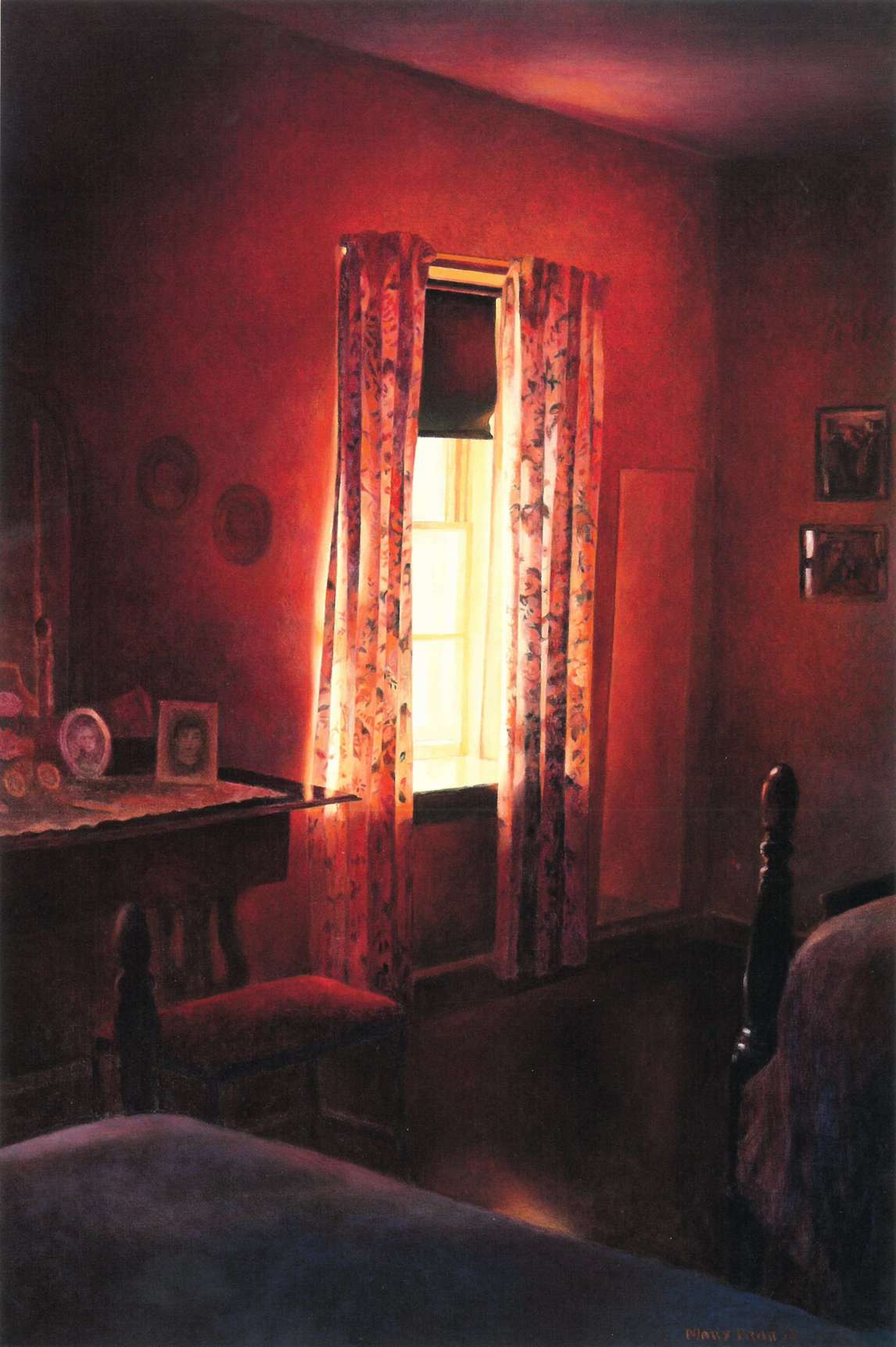

Despite this turmoil, Pratt’s career was flourishing. The House inside My Mother’s House, a 1995 exhibition at Toronto’s Mira Godard Gallery, featured several new works, many of them paintings of the house on Waterloo Row in which she grew up (which by then had become her sister’s home). The “house” of the exhibition’s title was a dollhouse made by her father, a model of the family home, which is featured in the painting The Doll’s House, 1995. The dominant colour in Pratt’s paintings of her mother’s house is red, a rich, suffused glow in My Parents’ Bedroom, 1995, or a bright splash in The Dining Room with a Red Rug, 1995. Although she had become known for depicting domestic objects in close-up, there are relatively few spatial interiors in the work of Mary Pratt, and nothing else that comes close to the concerted look at one place represented by these works. Pratt’s mother died two years after the exhibition of these works, at the age of 87. (Pratt’s father had died in 1985.)

Later in 1995 the Beaverbrook Art Gallery mounted Pratt’s first retrospective. The Art of Mary Pratt: The Substance of Light was curated by Tom Smart and toured Canada for two years. Afterwards, Pratt’s career continued to grow, and she regularly exhibited at her two dealers, Mira Godard in Toronto and Equinox Gallery in Vancouver. Despite her growing success, however, she still felt like an art-world misfit, telling an audience in Fredericton, on the opening of her touring exhibition The Substance of Light, that being a realist alienated her “from the main stream of contemporary art.”

Between 1995 and 2002 Pratt worked on a series of woodblock prints, a collaboration with master printer Masato Arikushi (b.1947). In 2000 her book A Personal Calligraphy, a collection of journal entries, previously published memoirs, and speeches and lectures, was published. The book was well received, and in 2001 won the Newfoundland Herald Non-Fiction Award from the Writers’ Alliance of Newfoundland and Labrador.

Pratt continued to exhibit regularly in commercial galleries in Vancouver, Toronto, Edmonton, Fredericton, and elsewhere. A museum exhibition, Simple Bliss, was organized by Regina’s MacKenzie Art Gallery and toured the country from 2004 to 2005. This exhibition, curated by Patricia Deadman, featured works from the previous ten years, including the entire suite of ukiyo-e prints realized with Arikushi titled Transformations. Pratt remarried in 2006, to U.S. artist James Rosen, and they divorced a decade later. “I’ve always landed lucky,” Pratt said in 2014, “except for men.”

In 2013 Mary Pratt, a retrospective exhibition jointly organized by The Rooms and the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, also toured the country. It featured works spanning the entirety of her career. Co-curated by Mireille Eagan, Caroline Stone (both curators at The Rooms, St. John’s), and Sarah Fillmore (curator at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, Halifax), the exhibition opened in St. John’s in May 2013 and then travelled to the Art Gallery of Windsor, the McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg, and the MacKenzie Art Gallery, Regina. Its last stop was the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, Halifax, closing in January 2015.

Despite turning down this retrospective exhibition, the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, did mount an exhibition of Mary Pratt’s work in 2015, as part of its Masterpiece in Focus series. Titled This Little Painting and co-curated again by Eagan and also by National Gallery of Canada curator Jonathan Shaughnessy, the small exhibition was mounted concurrently with an Alex Colville retrospective. The title came from how Mary had described Red Currant Jelly, 1972, her first work acquired by the National Gallery. The exhibition marked the first time that the Masterpiece in Focus series featured a living artist.

When Mary Pratt died in St. John’s on August 14, 2018, she was one of the country’s most popular artists. Former governor general Adrienne Clarkson, who had been Mary’s close friend for forty-five years, wrote, “Mary created a body of work that is second to none in the history of art in Canada. She knew the time would come when people would say her vision counted and embrace her idea of what must be looked at, which combined both beauty and pain.” Mireille Eagan wrote that Mary “showed us how to hold, to cherish, a moment before we must inevitably turn to resume the day.” This echoes one of Mary’s own statements, from 2000: “And so I roll my life along, trying to hold it together—keeping what I love, refusing to admit to loss, allowing layer after layer of pleasure to distract me from realities I have no ability to change.” Mary Pratt had to deal with many realities that she could not change, but she persevered and became, in the words of Clarkson, “our greatest female painter since Emily Carr.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements