Threads of Scarlet, Pieces of Pomegranate 2005

Mary Pratt, Threads of Scarlet, Pieces of Pomegranate, 2005

Oil on canvas, 91.4 x 61 cm

Private collection

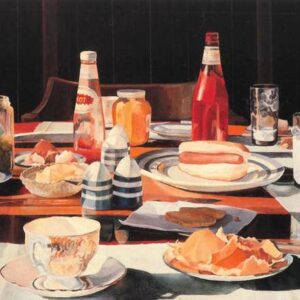

Of all the fruit Mary Pratt chose as subjects over the years—bananas, cherries, oranges, grapes, and apples—she most consistently returned to pomegranates. The pulpy fruit, with its vibrant red seeds, has a charged sexual connotation notable throughout art and culture and proved irresistible to her. Her 1993 painting Pomegranates in Glass on Glass, for instance, shows the fruit torn open and dripping pulp and seeds. There is something of a ritual killing in the work, as if the torn asunder fruit were a sacrifice.

This work from 2005 makes the allusion more extreme, and was completed just after the artist’s divorce from Christopher Pratt became final in 2004. (They had lived separately for twelve years.) In an interview about her final retrospective, Mary said of the painting, “It seems to almost drip with blood. I did it unconsciously, really, I didn’t remember doing it or seeing it.”

The pomegranate pulp and seeds read almost as flesh, reminiscent of a painting of a raw piece of meat, such as Sunday Dinner, 1996. As with Sunday Dinner, the pomegranates are presented on a reflective silver surface—tinfoil rather than a formal platter. The play of reflected light unsettles the surface, agitates it, heightening the unease and sense of violence that the painting conveys.

Over her last productive decade of work Mary Pratt often revisited previous themes and tended to focus on still lifes such as this one. The treatment of Threads of Scarlet, Pieces of Pomegranate is more dramatic than much of her earlier work, with the pomegranate juice spattering the tinfoil. It is a technically challenging piece, with its multiple reflections and translucent juice, and conveys Pratt’s distinctive interest in contained violence. In writing of another pomegranate painting of Pratt’s, Robin Laurence points out that the pomegranate seed has long been a symbol of fertility, “[falling] along a continuum of passion, conception, nurturance, and death.”

The powerful “erotic charge” Pratt saw almost forty years earlier in the red, rumpled chenille bedspread of The Bed, 1968, remains in play here. Pratt herself has said, “Red isn’t just a colour, it’s an emotion.” In an interview with curator Jonathan Shaughnessy, she elaborated:

There’s no doubt that I came from a house that was riddled with red. Red carpets and a belief in red somehow or another. My mother used to be a painter, and of course a cook and so on. And she said, “Isn’t it always so wonderful to put a cherry on at the end, because it’s so beautiful?” And it makes the point: it’s red, it’s beautiful. And, of course, the jelly that we had was usually red, and it would sit in place of honour at the table at Thanksgiving and at Christmas. My mother said it was best to leave the red till last, leave the best till last—red is the best, but don’t start with it.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements