The work of William Brymner (1855–1925) has long resisted stylistic definition. Although he trained in France in the academic tradition, he was also committed to painting en plein air and was one of the earliest Canadian artists to write about Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. Most of his well-known works were accomplished in oils, but at the height of his career he explored the medium of watercolour to much critical acclaim.

The Academic Tradition and the Nude

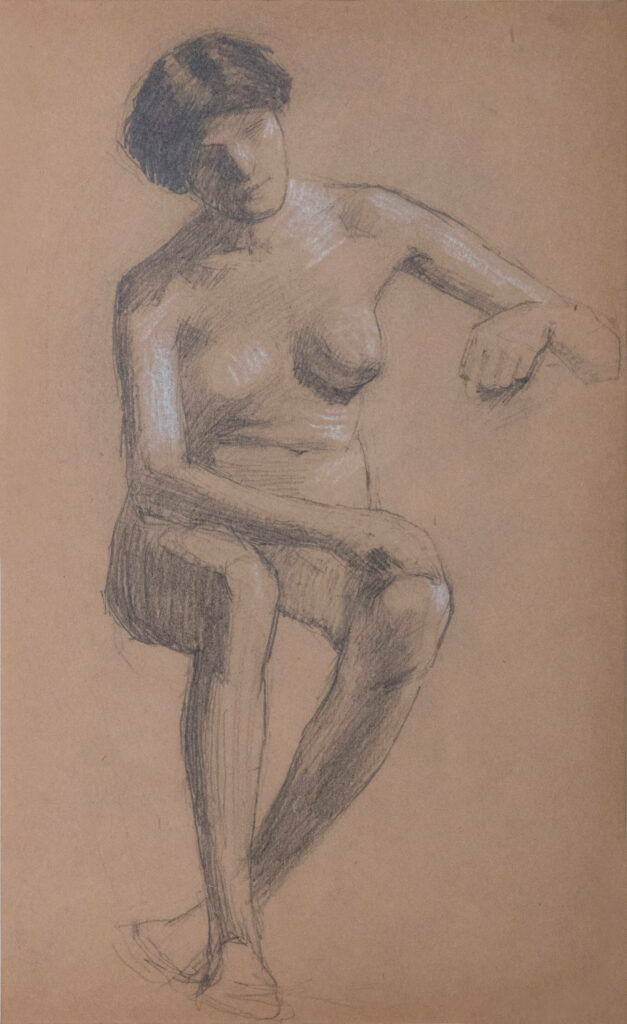

For William Brymner and many of his contemporaries, drawing—particularly drawing the human figure—was an essential artistic skill. Critics recognized drawing as a quality within paintings: it was the foundation beneath the colours, the underlying formal structure. Brymner’s “drawing” within his paintings was often admired. He studied drawing at great length and valued highly the craft of draftsmanship.

Brymner’s early training took place in French art schools where students normally progressed from drawing casts to drawing the live model, and his formal studies emulated this academic tradition. The nude was often seen as the greatest test of an artist’s drawing ability. After Brymner had spent several weeks working from casts, only then did he begin drawing live models, both men and women, but he found drawing a woman’s torso “the most difficult thing to do. . . . I know I couldn’t have tried it last October.” When he wrote this to his father in the spring of 1884, Brymner had been studying art for six years. He would continue to work on the human form for decades, and he made it a core element of his teaching at the Art Association of Montreal.

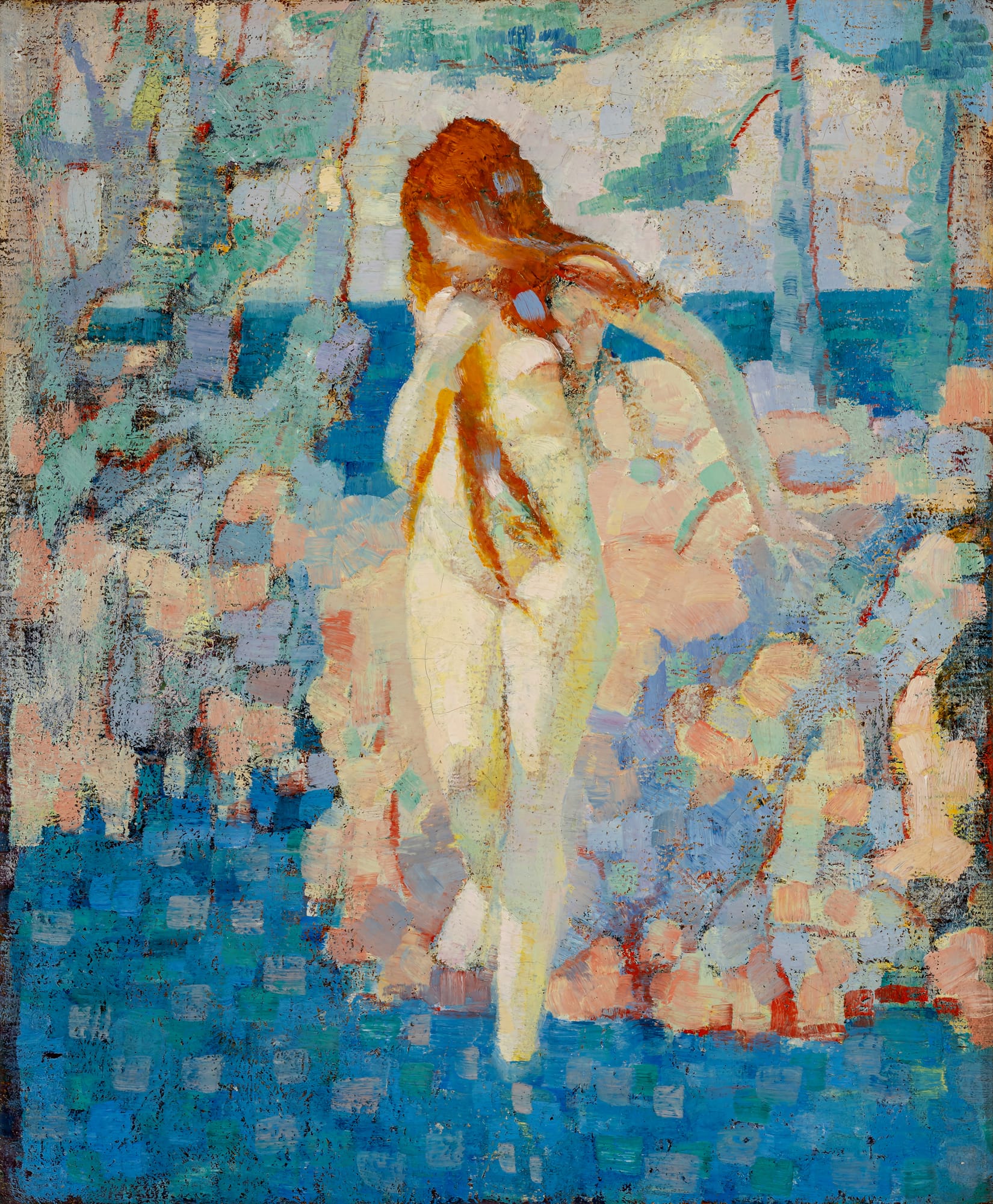

Brymner’s efforts from the 1910s to paint the female nude developed out of his early studies in France. Reclining Nude, c.1915, Standing Nude, n.d., and Nude Figure, 1915, exemplify the challenge of the subject. In these works, Brymner captured the contours of the muscles of the women’s bodies and the play of light across them with masterful subtlety. The women’s surroundings, a nondescript landscape and a studio, are sketch-like in comparison—no doubt to focus the viewer on Brymner’s abilities in depicting the human figure.

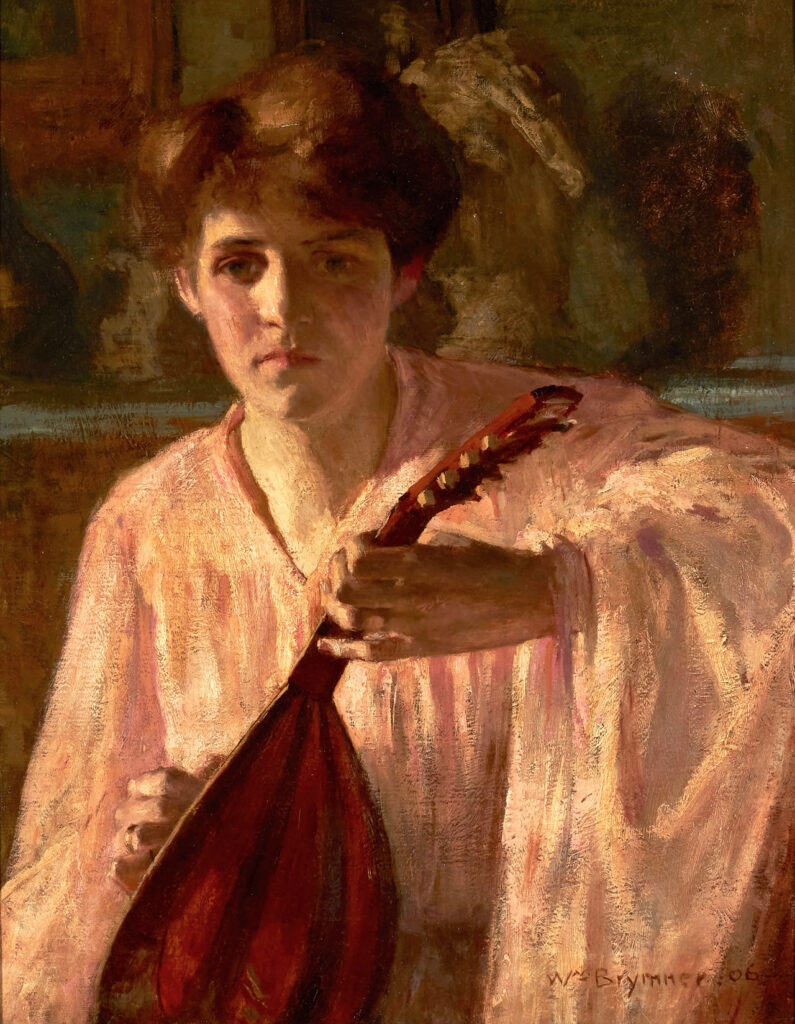

Although drawing could be an important part of a landscape, it was seen as particularly important to artworks that represented people, because it was the underlying drawing that gave a body its structure and verisimilitude. For these reasons, critics considered drawing in relation to paintings that depict clothed figures as well as nudes; for example, when Brymner exhibited Prelude, 1906, the figure was praised as “well drawn.” The ability to represent a person’s flesh such that it seems natural and vital was also discussed in more general terms. In analyzing Brymner’s The Trinket (Jeune fille au chapeau bleu [La breloque]), 1916, a critic commented, “Especially well managed is the painting of the flesh through the transparent material of the sleeves.” The woman depicted is wearing a fashionable contemporary dress, but Brymner was still demonstrating his mastery of the human body.

Brymner’s conviction that drawing was fundamental to artistic training was evident in his teaching and writings. He demanded his students approach it rigorously, often telling them to start over, but he did not expect them to perfect a particular style. Instead he emphasized that learning to draw was not about learning to copy, but about learning to see. Brymner described it as “the foundation of all the graphic and plastic Arts,” and stated that “the primary object of an Art training is, to teach people to look at nature intelligently” and that “the mind can be more easily trained to observe nature with exactness by the study of the nude model than in any other way.” For Brymner, drawing was ultimately an intellectual exercise, and the process was at least as important as the work itself.

Watercolour

Today, Brymner’s most famous works are oil paintings, but at the height of his career he was widely admired for his ability to work in watercolour. Compared with oil paint, watercolour is highly practical and easy to use when an artist is on the move because it can be prepared swiftly and it dries quickly. As an art student touring Belgium in the summer of 1879, Brymner abandoned his oil paints for watercolours because they were easier to carry while travelling on foot. This was one of the earliest of many trips on which Brymner used watercolour. Île-aux-Coudres, c.1900, for example, is a graphite drawing with watercolour applied on top of the sketch, and it was likely made during a summer boating trip in Quebec.

The convenience of watercolour made it ideal for informal works. Brymner used watercolour for preparatory sketches for oil paintings, for his contributions to the creative workshops organized by the Pen and Pencil Club, and even, occasionally, for decorating a menu. He sometimes inscribed watercolours and presented them to his friends as gifts; a small painting of a young girl done in 1897, for instance, was given to James Wilson Morrice (1865–1924).

Although watercolour was highly convenient for creating sketches, Brymner also prepared more formal watercolour paintings and was regularly exhibiting these works by the mid-1890s. He submitted watercolours to the annual exhibitions of the Art Association of Montreal and the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, and in 1894 and 1896 he held solo shows specifically devoted to watercolours. The choice to exhibit his watercolours suggests that Brymner was using the medium strategically as a potential source of sales. With the exception of particularly large works like The Grey Girl, 1897, Brymner’s watercolours were often priced considerably lower than his oil paintings. As a result, they occupied a distinct, more affordable, position within the art market that made them easier to sell. Given Brymner’s perpetual financial worries, he likely hoped that the sale of his watercolours would bolster his finances.

Brymner devoted considerable time to working in watercolour. A letter he wrote to Clarence Gagnon (1881–1942) in 1908 mentions that he had spent almost the entire summer working in the medium. This fluency garnered him much critical acclaim. Critics admired his exhibition watercolours, praising him for exploiting the paint’s delicacy to create striking images. In 1898 he exhibited two dozen watercolours as part of a Christmas exhibition at the AAM; The Black Schooner, 1898, and Waterfall, 1898, are believed to have been among the works. In reviewing the show, the Montreal Gazette claimed that Brymner’s art “has something more than the ordinary degree of vitality” and “his work impresses one by the simplicity of subject, out of which he can make a picutre [sic] excellent in tone, composition and color, and at the same time interesting in the general feeling conveyed.”

By the early 1900s watercolour was integral to Brymner’s reputation. In 1903 a critic for the Montreal Witness declared: “We have one real watercolorist among us in the person of William Brymner. He . . . shows you watercolor for what it is, in all its delicacy and purity. . . . After his draughtsmanship, we consider it his strongest point.” There were even critics who claimed that he was more gifted in watercolour than oil. In Harriet Ford’s view, watercolour seemed “to suit Mr. Brymner’s powers, and [it] forces him to the reticence and delicacy which are lacking in his handling of the more vigorous medium.” For Brymner, watercolour had become a triumphant material.

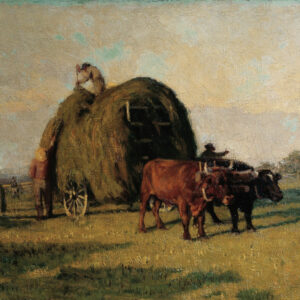

Working en Plein Air

When Brymner was studying in Europe in the late 1870s and 1880s, working outdoors was increasing in popularity among European artists. Although the Impressionists are the most famous artists to practise painting outside, artists associated with the Barbizon school, perhaps most famously Théodore Rousseau (1812–1867), did so as well. This practice is now known as painting en plein air, but for Brymner, en plein air had an even deeper meaning: it meant “that instead of painting a figure in the house with studio light when you wish to show it as doing something outside, you should paint the figure as it would appear in the open air.” Brymner credited this practice to Édouard Manet (1832–1883), though he acknowledged that he had learned of it before he encountered Manet’s works at the memorial exhibition held for Manet at the École des beaux-arts in 1884. The principle demanded that figurative works as well as landscapes be painted outdoors, and it was very important to Brymner.

As a young man, Brymner was sharply critical of artists who worked from photographs. Throughout his life he believed that in order to depict the natural world he had to observe it directly. When he was working on the canvas of his most famous outdoor painting, Border of the Forest of Fontainebleau, 1885, Brymner worked outside under an umbrella for over a week. Many of his small oil sketches and his watercolours were likely painted outdoors as well. Painting en plein air was perhaps the most effective way to get close to nature, and for Brymner, nothing was more important.

Brymner often experienced significant practical challenges to working outside. During his visit to Yorkshire in 1884, he complained, “The wind is blowing still very hard and makes it perfectly impossible to paint outside on account of the dust and sand that gets on the Canvas and Palette!” In 1892, reporting on his work in the mountains, he noted, “I need not tell you what a very bad summer we have had for rain and mosquitoes.” As annoying as the mosquitoes must have been, rain and clouds in the mountains could prevent artists from seeing the subject they had travelled to Western Canada to paint. Brymner encountered similar problems elsewhere in Canada. Writing to Clarence Gagnon about his visit to Île d’Orléans in 1904, Brymner stated, “I believe it is snowing on the hills opposite. I am trying to finish things & [can’t] as we for the last six weeks have been having 3 days rain to one of fine weather.”

These myriad practical nuisances encouraged Brymner to develop a hybrid approach to painting nature. He became more strategic about using sketches to complete works in the studio. During his 1892 visit to the Rockies, he prepared drawings and made field studies (Mount Baker, 1892, may be one of them), and he made plans to use photographs in his studio, an aspect of his practice that merits further research. In his letter to Gagnon, he concluded, “I think you have to make endless studies outside but I believe the picture has to be painted inside.” He was acutely conscious of the problem of shifting weather, noting that if one worked outside, “you must keep changing & changing the effect—Except in a country of eternal sun. Delacroix, Millet, Turner almost never did it. . . . At any rate I’d defy any one to have painted a picture of any size outside here this summer.” He had faced the same challenges of changing weather decades earlier when he completed A Wreath of Flowers, 1884, but as a mature established artist with substantial professional commitments, he was no longer prepared to wait for better weather.

Brymner’s landscapes vary considerably in their approach to light, colour, and form, but his foundational principle of studying nature was consistent throughout his career and was admired. In an article on Canadian landscape art, Eric Brown declared, “His work is sincere and painstaking: there is no striving after novelty or new colour, but the simple truths of nature’s changing expression are given with a steady and sober earnestness which remains where much superficial brilliance fades.” Brymner’s painting Early Moonrise in September, 1899, was included as an illustration: begun on a trip to the countryside, it reflects his abiding commitment to painting nature on his own terms.

Impressionism and Modernism

Brymner witnessed some of the most radical developments in Western art, but he never fully embraced any particular style. As a mature artist he took an interest in Impressionism, a style made famous by artists such as Claude Monet (1840–1926) and Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919) and known for its revolutionary use of colour to capture impressions of light and forms, as well as its depiction of modern life. Though Brymner rejected strict adherence to a style, Impressionism influenced elements of some of his later works. In the Orchard (Spring), 1892, for instance, brings together a modified academic approach to figures with an approach to nature that is closer to that of the Impressionists: he painted the people with care but the blossoms on the trees are merely expressed as dabs of pale pinks and white. This individuality of expression is in keeping with his approach to teaching: he encouraged his students to experiment and explore.

Brymner’s interest in the art movements of his day are evident in the art lectures he gave. He delivered talks on Impressionism, first in March 1896, for the Women’s Art Association of Canada at the YMCA in Montreal, and then in April 1897, for the Art Association of Montreal. These lectures have ensured him a place in the history of Impressionism in Canada, though neither his writings nor his works wholeheartedly embraced the style. He did not see Impressionism as an extreme departure, but as a new approach to creating vitality in art. Observing that the famous Impressionist artists Edgar Degas (1834–1917) and Claude Monet were in fact “entirely different,” he concluded that “the first and principal tenet common to all is an intense love of and respect for nature and determination to give the exact character as they themselves see it.” Brymner believed in this core principle, and as he worked out how to express what he saw, he was open to the solutions the Impressionists offered.

In paintings from his later career, Brymner continued to experiment with form and colour in ways that might be considered Impressionist. In works such as Girl with a Dog, Lower Saint Lawrence, 1905, Brymner presents a carefully modelled figure, but the handling of the paint is bolder; rough brush strokes capture the play of light on the girl’s clothing and the distant horizon—a hallmark of the Impressionist style. Like the Impressionists, Brymner was fully prepared to work with bright colours. When he exhibited Summer in 1910, he was praised for “brilliant Canadian summer green being most truthfully rendered with a very luscious and juicy quality of pigment.” October (Octobre sur la rivière Beaudet), 1914, is a more muted work, but the extraordinary silhouettes of the trees suggest that Brymner may have wanted to experiment with flattening a landscape, an approach to space that is apparent in many Impressionist works, including Monet’s series of paintings of haystacks and poplars (The Four Trees, 1891, is a good example of the latter).

Brymner was critical of the Post-Impressionists (at least the European ones), a group of artists who were creating radically different works that built on the Impressionists’ experiments with colour and form. Although he believed that Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890), and Paul Gauguin (1848–1903) had expressed themselves as best they could, he felt that their followers had repudiated “entirely any imitation of nature,” producing a “mass of rubbish.” He was critical of Henri Matisse (1869–1954), for instance, because he believed Matisse could draw “draw as well as anyone, but in order to live up to his creed he has to draw things all out of proportion and pretend to be simple.” Brymner’s views here are consistent with his own practice: his commitment to studying nature continued throughout his life.

However, when Canadian artists exhibited works inspired by the Post-Impressionists and were labelled as such, Brymner was supportive. In 1913 the Art Association of Montreal exhibition included works by the artists Randolph Hewton (1888–1960), John Lyman (1886–1967), and A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974) that attracted severe criticism from critics and from other artists; works such as Jackson’s Assisi from the Plain, 1912, were considered highly radical. A review for the Montreal Witness declared that “disciples of the Post Impressionists” had “invaded” the exhibition, using “immensity of canvas, screamingly discordant colors, and execrable drawing . . . to jar the public eye.” Brymner defended the artists to his colleagues and in the press, declaring that Hewton and Jackson (whom he had known as students) were “extremely promising men” and that “while I may not care for some pictures personally, I recognize that they represent a phase of modern work which should interest the public to see.” Anne Savage recalled that during a visit to the AAM exhibition Brymner stopped next to some people gathered around Lyman’s work. “He looked absolute fire at the group . . . and he said ‘Well, if a man wants to paint a woman with green hair and red eyes, he jolly well can.’ And he stomped off.” This anecdote illustrates his deep commitment to the need for artistic experimentation, as well as an abiding sense of loyalty to his students, colleagues, and peers.

Ultimately, in his own works Brymner chose to draw on Impressionism and other modern approaches without truly embracing these styles. In reviewing one of Brymner’s memorial exhibitions, the Montreal Daily Star observed that “it is almost hard, on first sight of the pictures, to grasp the fact that they are all the work of one man.” Noting that Brymner’s artistic practice had long been entwined with (and interrupted by) teaching, the review concluded that with every new artwork, Brymner began “not only with different aims but sometimes even with new technical methods, but in every case he got something which was well worth having.”

Brymner’s enthusiasm for numerous creative experiments ensured that his oeuvre must be described as diverse, but it is also highly individual, a quality that Brymner valued deeply. Commitment to personal innovation was perhaps the most compelling lesson Brymner taught his students. In balancing open-mindedness with his artistic goals, he not only developed his own painting, but he earned his students’ trust, giving them powerful encouragement to take their own works and, by extension, Canadian art in new directions.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements