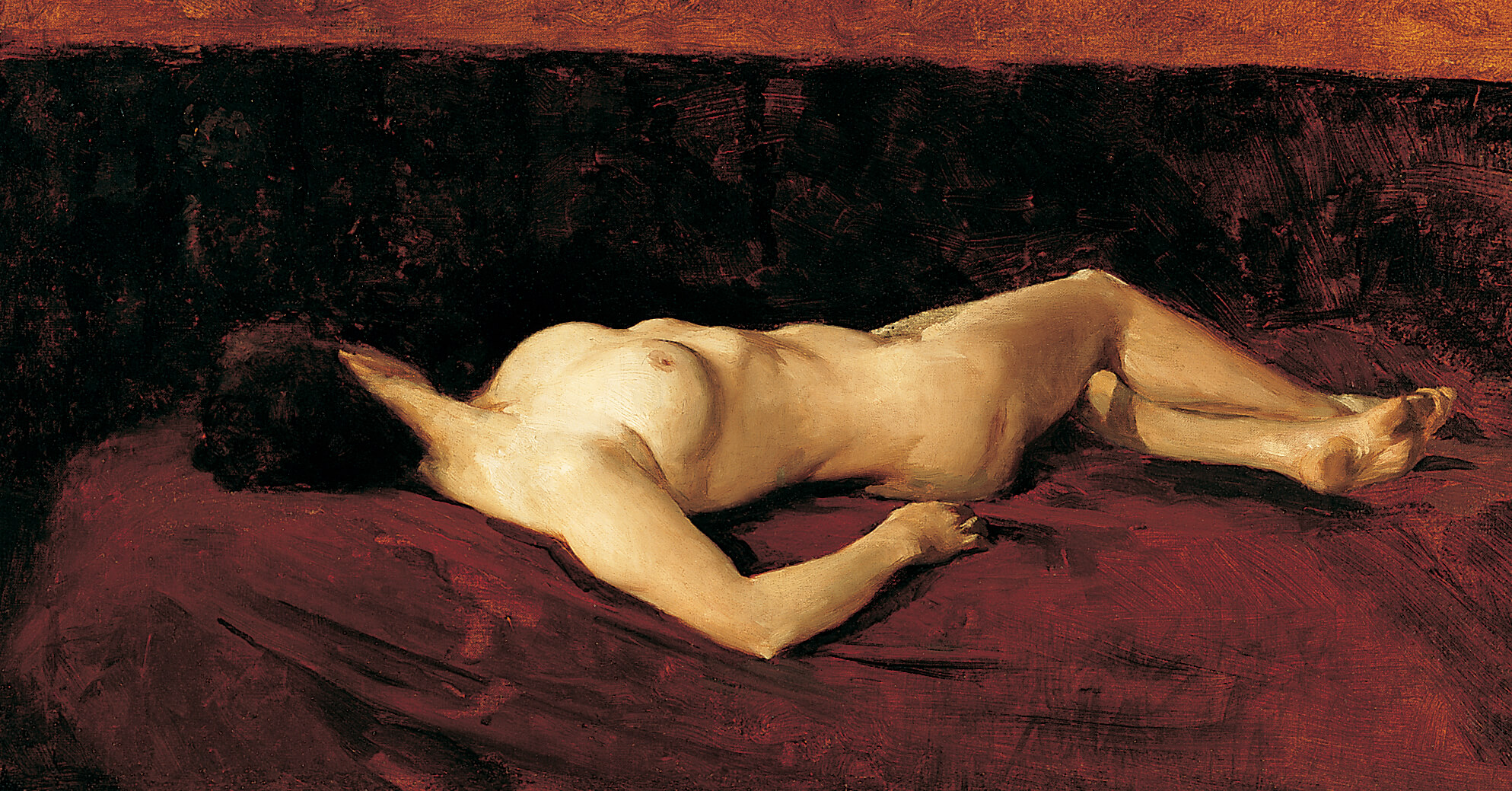

Nude Figure 1915

William Brymner, Nude Figure, 1915

Oil on canvas, 74.7 x 101.7 cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

In the 1910s Brymner worked on paintings depicting the female nude, and this series was one of his last substantial projects. He completed at least four paintings that focused on a nude woman lying on her back. Nude Figure, a work exhibited in 1915, is both representative of the group and the most high profile, as it was acquired by the National Gallery of Canada. It became a controversial work: nude women subjects were common in nineteenth-century Western art, but they were not commonly seen in Canadian exhibitions. The painting is important to Brymner’s oeuvre, however, not because of the controversy but because it represents the last major development in a career that had been characterized by diversity. Nude Figure was a radical contrast to Brymner’s landscapes and seascapes.

As a young man, Brymner studied the academic tradition and the nude. He felt that this particular pose was a difficult one to work with, observing gloomily that “a girl lying down with a white skin is not an easy piece of work, especially as she never gets the pose twice exactly the same.” His decision to return to nudes so late in his career may have been influenced by a critic’s observation that a recent Canadian exhibition had lacked a good nude, then a highly prestigious subject.

Alternatively, he may simply have been looking for a new subject that would enable him to demonstrate the full range of his talents and attract attention. After so many years of studying art, he would have known many paintings of the female nude that he might have turned to for inspiration. His former teachers Jules-Joseph Lefebvre (1836–1911) and William Bouguereau (1825–1905) had painted nudes many times, and the subject was one that Brymner’s students and former students were also interested in—for instance, Randolph Hewton (1888–1960) had exhibited modern nude compositions at the Art Association of Montreal in 1914.

Critics analyzed Nude Figure in stylistic and technical terms, praising it as “an admirable study in light and shade” and “excellent as to drawing and flesh tones. . . . The dull blues and reds of the cushions on which the figure is reclining help to bring out the ivory tints.” But the subject matter was what caught the public’s attention. According to Corinne Dupuis-Maillet (1895–1990), one of his former students, when Brymner completed Nude Figure, the painting shocked people: “Brymner was a conservative person and that picture flabbergasted everyone—the reclining woman in that position, lying on her back.” Today it is somewhat difficult to appreciate just how surprised viewers were by this work.

Nude Figure proved to be a problem for the National Gallery. In 1916 Eric Brown, the director, wrote: “There has arisen some comment here on the propriety of Brymner’s nude. . . . I do not wish the National Gallery to be subject to even ignorant attacks on such matters and pending consideration of the matter I have removed the picture from exhibition.” In December of that year, Brown offered it to the future Group of Seven artist Arthur Lismer (1885–1969) for the Victoria School of Art and Design in Halifax, suggesting that the work was “not a gallery picture but . . . a frank study of the figure.” Lismer quickly declined the loan, explaining that although he would personally welcome it, the painting “would prejudice the Halifax public against the school.”

As president of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, Brymner represented Canada’s artistic establishment, but in one of the final twists to his career he created a work that was perceived as provocative and controversial. The painting shocked viewers—a fitting final milestone in a career dominated by a commitment to ongoing personal innovation.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements