Inspired by his travels, William Brymner (1855–1925) painted everything from Canadian landscapes to the canals of Venice. His paintings of the Rocky Mountains and rural Quebec contributed to notions of Canadian identity, and he strove to ensure that Canada became part of the international art community. For Brymner and his peers, a distinctly Canadian style for art was important, but so was the space in which they would show it to the world. He achieved critical success while teaching at the Art Association of Montreal for more than thirty years, where he was an inspiration for his many students. As Clarence Gagnon noted, “If Brymner couldn’t teach you, nobody could.”

Looking Abroad

Throughout his life and career, William Brymner was convinced that visiting Europe was important for his professional development as an artist. He saw Europe (and Paris in particular) as the centre of the Western art world, with its numerous art schools, museums, exhibitions, and artistic communities. He was also aware that many Canadian collectors valued European works over works by artists from their own country, and that both collectors and critics admired artists who understood European art traditions. Many of Brymner’s Canadian contemporaries were also looking abroad for inspiration. Although some of his peers studied in the United States (where numerous artists and collectors were also turning to Europe), Brymner did not. In his later life he encouraged his students to study in Europe, and he lectured on and discussed modern European art with them.

Today, late nineteenth-century Paris is closely associated with the Impressionist movement, but Brymner went to Europe to study the academic tradition, an approach that required the artist to learn to depict forms naturalistically rather than embracing impressions of a scene. The two methods could not be more different: as Tobi Bruce notes, “the system of instruction that drew artists [like Brymner] to Paris was utterly at odds with Impressionism.” Brymner eventually took an interest in Impressionism, but in general he was attentive to an extraordinary range of artworks, from medieval sculptures to works by contemporary artists. He was not drawn to Europe by any specific style of modern art. If anything, he was more interested in the Old Masters, admiring painters such as Paolo Veronese (1528–1588) and Titian (Tiziano Vecellio; c.1488–1576). As a mature artist Brymner did not believe in emulating a particular school of art. Instead he was committed to extensive and ongoing learning; he was inspired by the ideas of other artists rather than their styles.

Besides his early studies in Paris, Brymner made numerous trips to Europe. His motives for these visits are underscored in a review published in the Globe (Toronto) in 1892, written by Canadian poets Archibald Lampman and Duncan Campbell Scott, who claimed that “in a land like Canada, where we have practically no great pictures available and no eminent resident artist, the young painter . . . must go abroad; he must seek in the ateliers and in the galleries of Europe for the practical insight which he could never obtain at home.” The same Globe review later identified Brymner specifically as one of the Canadian artists “who has had the advantage of the [French] schools.” The reviewers praised A Wreath of Flowers, 1884, most likely because Brymner’s careful depiction of the little girls’ figures highlighted his French academic training.

But Brymner’s trips to Europe were not made solely for his education. He was well aware that working in Europe would shape his public reputation. His travels were critical to his identity as a cosmopolitan artist in Montreal; for instance, his painting Border of the Forest of Fontainebleau, 1885, alludes to his familiarity with the Barbizon school, a French group of artists whose works were popular with North American collectors in the late nineteenth century. For Brymner, travelling in Europe was a professional investment because his patrons would have seen his experience as a sign of well-informed, sophisticated artistic judgment, but it was also a pleasure for him. In a letter written to his friend Kenneth Macpherson (1861–1916) from Martigues in 1908, Brymner noted, “The beauty of it is partly that there have been so many generations of painters here that . . . they have an extraordinary respect for anyone with a paint box.”

Brymner’s many trips enabled him to create numerous works depicting subject matter that was known to be European. One of the earliest paintings he exhibited in Canada was With Dolly at the Sabot-makers, 1883, a work quickly recognized as a French subject and the first of his works to be acquired by the National Gallery of Canada. In later years Brymner visited France, Ireland, the Netherlands, and Italy, and he created artworks inspired by his journeys. His painting Ruin of a Church, 1891, for instance, is a portrayal of the ruins of Muckross Abbey in Killarney, and In County Cork, Ireland (Dans le comté de Cork, en Irlande), 1892, depicts an Irish village.

Whenever he wrote or lectured on art, Brymner’s European experiences were vital to the reflections he shared. He viewed Europe’s most famous sites, from the Eiffel Tower to the canals of Venice, with an artist’s talent for visual analysis: “The general colour of Venice is a grey rose colour running into all kinds of other greys, and old faded greens and yellows. These colours lighted by the late afternoon sun and reflected . . . make a wonderful harmony.”

His other lectures, on drawing and on Impressionism, and his article “Progress in Art,” published in the University Magazine in April 1907, are packed with references to European artists and to his experiences in viewing their works. For example, Brymner made special efforts to view works by Frans Hals (c.1582–1666), reporting to his father in a letter that the paintings in the museum in Haarlem “were worth coming all the way to see.” He admired Hals’s use of colour and the vitality in his work, declaring that the portraits were “painted in the most straightforward way I have ever seen.” He would later cite Hals’s work in his lecture on drawing, simultaneously teaching his students about the Old Masters and demonstrating his expertise. The depth of his commitment to his travels abroad demonstrates his genuine belief in the importance of these studies, even as he was also aware that his lectures and writing on European art enhanced his reputation.

Encounters with Indigenous Communities in Western Canada

The beginning of Brymner’s career coincided with tremendous change and violence in Western Canada. He first visited the region in 1886, travelling on the brand-new Canadian Pacific Railway. At the time, the borders in Western Canada were very different. Saskatchewan and Alberta would not become provinces until 1905; in 1886 these lands were part of the North-West Territories. The governance of the entire region, including Manitoba, had been transformed by the numbered treaties with Indigenous nations. Treaties 1 through 7 were signed between 1871 and 1877, and created a system of reserves (a critical adhesion to Treaty 6 was signed in 1882). In the wake of the North-West Resistance of 1885, in which Canadian government forces fought the Métis people, there was an intensifying interest in the control of Indigenous people as the region was attracting increasing numbers of settlers. By 1886 the federal government was attempting to force Indigenous people to settle on the reserves and to assimilate.

Brymner was made aware of these events in several ways. In addition to what he might have learned from newspapers, his father was an archivist for the federal government, and he also had a brother who was in the North-West Mounted Police during the Resistance of 1885. Brymner’s trip out west in 1886 brought him into direct contact with Indigenous people. (Though there were many First Nations communities in Eastern Canada, there is no record of Brymner meeting them.) He would have met Indigenous people from different nations. He stayed on the Siksika Nation Reserve near Gleichen (now in Alberta) for over a month, and there were Cree (Nehiyawak) visitors there at the time. Later in his trip he may have met Indigenous people in British Columbia as well.

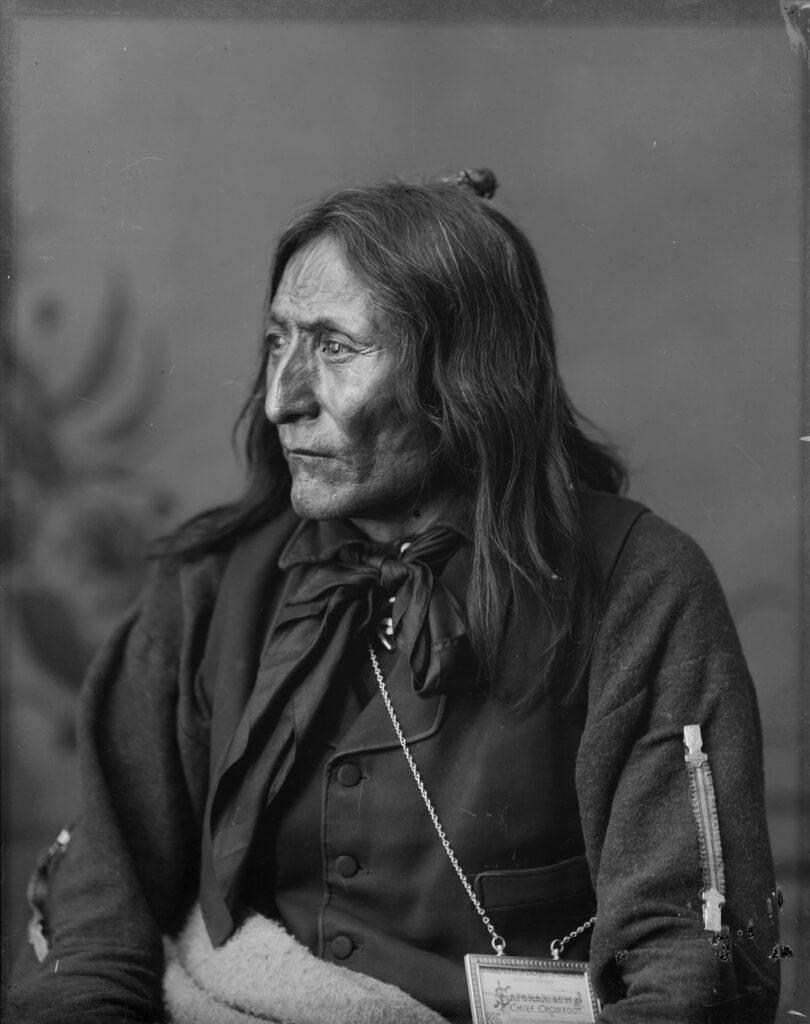

In 1909 Brymner wrote a detailed account of his visit to his friend Edmund Morris (1871–1913), an artist who was passionately interested in Indigenous people and history. The letter reveals the extent to which Brymner became involved with the Siksika community during his visit. While he was there, Pihtokahanapiwiyin (then called Poundmaker in the Canadian media) arrived to visit Isapo-Muxika (then called Crowfoot), his adopted father. Pihtokahanapiwiyin was one of the most important leaders of the period and a key negotiator in Treaty 6. In the wake of the North-West Resistance, the federal government accused him of supporting Louis Riel, the leader of the uprising, and charged him with treason-felony. Pihtokahanapiwiyin was exonerated of these charges in May 2019; in fact, he had intervened to prevent Indigenous warriors from pursuing Canadian soldiers and today he is regarded as a peacemaker. After being imprisoned for nine months, he was released in March 1886 due to poor health; he died while visiting Isapo-Muxika. Brymner did not meet Pihtokahanapiwiyin, but he requested permission from the Canadian government authorities (most likely from Magnus Begg, the local Indian agent) to attend Pihtokahanapiwiyin’s burial. Brymner not only witnessed the ceremony, he assisted with preparations for the burial and with the interment. He was not invited, but he undoubtedly knew of Pihtokahanapiwiyin’s fame and he was evidently curious.

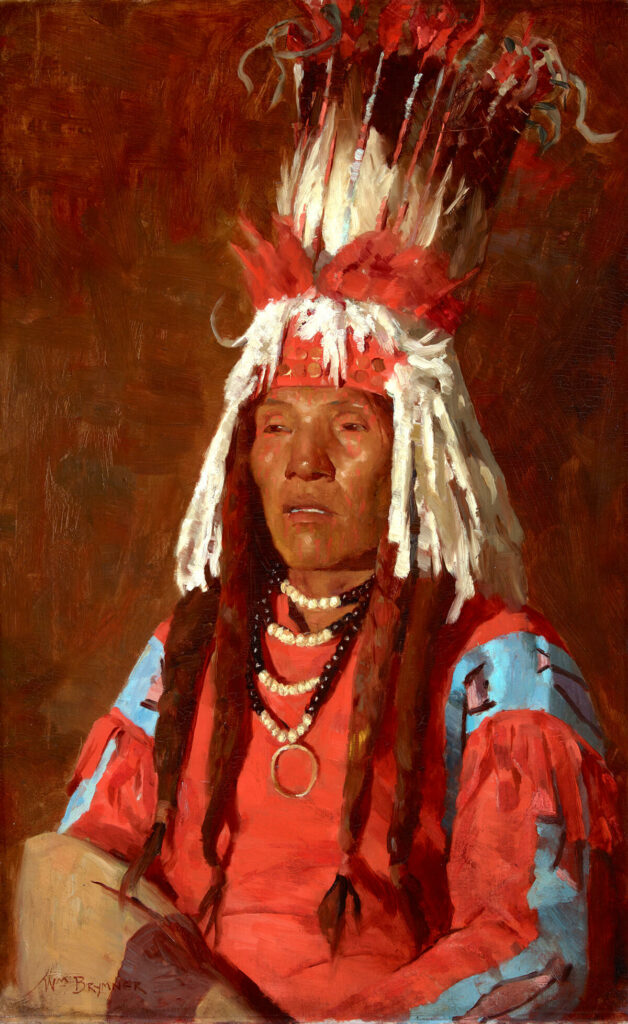

Although the total number of paintings of Indigenous subjects Brymner created is unknown and some works cannot be traced today, he is known to have painted studies of Indigenous people’s heads, including Blackfoot Chief, c.1888 or 1906. These works were likely intended to emulate the ethnographically inspired portraits by artists such as George Catlin (1796–1872) and Paul Kane (1810–1871) that are now recognized as perpetuating stereotypes. However, Brymner’s most complex works depicting Indigenous people, Giving Out Rations to the Blackfoot Indians, NWT and Yale in the Morning, B.C. (Fraser Canyon), both 1886, are startling because of their contemporary elements and their avoidance of stereotypes. It is unknown if Brymner wished to make a specific political critique, but he certainly knew that his subject matter was highly charged.

When he was visiting the Siksika Nation, Brymner painted Giving Out Rations to the Blackfoot Indians, NWT, 1886, a scene showing the distribution of food rations. This depiction of modern colonial violence refuses to offer any romanticized view of the past. Later in his trip when he went to Yale, British Columbia, he visited All Hallows School, an institution that Anglican missionaries had established in 1884 with the intention of educating and converting Indigenous girls. By 1886 the school was beginning to function as a form of residential school, and at the time of Brymner’s visit the bishop had begun to advocate for government support; an agreement would be reached in June 1888. Brymner depicted nuns and pupils at the centre of his 1886 work Yale in the Morning, B.C. (Fraser Canyon). The figures are small, but the nuns’ habits are recognizable, suggesting that Brymner wanted his viewers to see this as a contemporary scene. It is a painting that records an early moment in the development of the Canadian residential school system.

Overall, Brymner’s experiences and works are different from what we might expect from a colonial artist working in Western Canada in the nineteenth century. His paintings were inspired by ethnography and an interest in realistic scenes, whereas other nineteenth-century colonial artists were known for romanticizing Indigenous subjects in their paintings. Paul Kane, for example, was known for works inspired by ethnography but also for spectacular scenes with dramatic landscapes and idealized depictions of Indigenous people, such as The Man That Always Rides, Blackfoot, c.1849–56 and The Constant Sky, Saulteaux, c.1849–56. Such views of nineteenth-century Canada, which typically fail to acknowledge the violence of colonialism, have been challenged by several contemporary Indigenous artists, including Carl Beam (1943–2005) and Jane Ash Poitras (b.1951). For example, in her 2004 work Buffalo Seed, Poitras incorporates a wide range of images (including a romanticized image of a buffalo hunt) to comment on the slaughter of the buffalo and its devastating impact on Indigenous people. Nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Canadian paintings that minimize (and often erase) the brutal oppression of Indigenous people have also been challenged through critical writings.

Brymner was aware of romanticized images of the Canadian West, but unlike many of his contemporaries, he was a witness to the impact of colonialism on Indigenous people in Western Canada. He did not choose to embrace a romantic vision. Instead he addressed the inhumanity of colonialism by depicting realistic scenes in paintings created at a pivotal moment in his career. Once he was back in Montreal he rarely returned to these subjects. Although he does not appear to have been deeply troubled, his vivid recollection of the events of 1886, as described in his letter to Edmund Morris more than twenty years later, suggests that the memories were powerful.

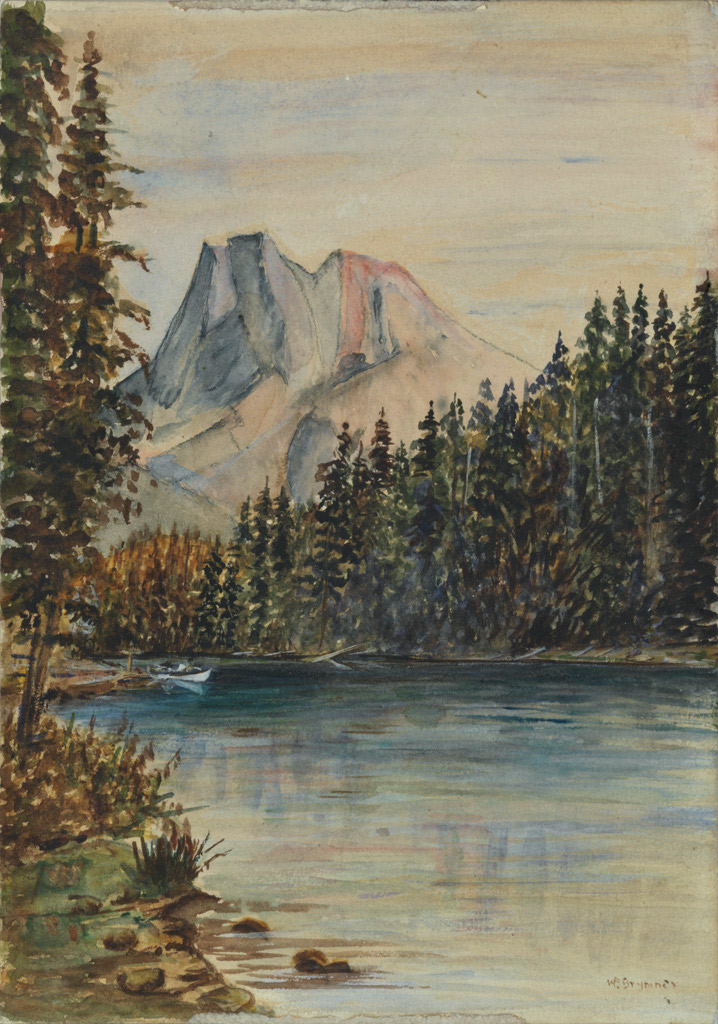

Painting the Rocky Mountains

In the 1880s the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) began promoting the Rocky Mountains as both a uniquely Canadian landscape and a national tourist attraction. As part of those efforts, the CPR’s general manager, William Van Horne, wanted mountain landscapes to be shown in exhibitions of Canadian art. Not only did the CPR support the exhibition of these paintings, but it adapted them for promotional imagery and souvenir booklets. Van Horne chose to work with prestigious artists. Lucius O’Brien (1832–1899), then president of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, was one of the first to whom he gave a commission: O’Brien’s Kicking Horse Pass (about 5000 ft), 1887, shows a spectacular mountain landscape with a train right in the centre. By 1889 Brymner had become personally acquainted with Van Horne, who assured him that he “could have a [railway] pass to the Pacific whenever I wanted one.” In the early 1890s Brymner found himself travelling to Western Canada to create works for the CPR. At the time he was highly conscious of the landscapes that artists like O’Brien had created, and he saw himself in competition with them.

In 1892 the Montreal Gazette noted that the CPR had commissioned Brymner to paint views of the Rockies for “the World’s fair [in Chicago], where they will, besides being good testimony of the progress of art in Canada, give hundreds of thousands of visitors to the fair an idea of the wonderful scenery to be found in the Canadian Rockies.” The paper described the project as “of a more ambitious nature” than Brymner’s work to date.

Indeed, Brymner’s mountain paintings are designed to make a powerful impact on the viewer. Many of these paintings are unusually large, ideal for commanding attention and surprising viewers who encountered them in exhibitions. Most of these works, such as Hermit Mountain, Rogers Pass, Selkirk Range, 1886, and Mount Cheops from Rogers Pass, c.1898, take a major peak as their primary subject, though a few, such as Sir Donald and Great Glacier, Selkirks, n.d., focus on views of glaciers and peaks. The viewer is presented with spectacular landscapes devoid of people. In these paintings, Brymner chose not to record the contemporary presence of Indigenous people, perhaps because his patrons had asked him not to do so. Often these works include the presence of a railway, which, in the nineteenth century, represented the unification of Canada and a new national identity.

Brymner’s own account of the CPR commissions to paint mountain landscapes for the world’s fair in Chicago demonstrates that he saw this project as a major undertaking. He wrote to Van Horne from Lake Louise and provided a detailed list of subjects he was working on, including Mount Baker, Yale, Ross Peak, Field, Lake Louise, and Lake Agnes. He also asked Van Horne’s advice: “If there is anything that you would suggest that should be done I will be glad to know.” He found painting the mountains difficult and, although he may have looked to European landscape traditions for guidance, his struggles suggest that foreign precedents failed him in the face of the Rockies’ grandeur. In the following decade Brymner painted several places in the Rockies, including Mount Cheops, Ottertail Range, Castle Mountain, Emerald Lake, Mount Sir Donald and Illecillewaet Glacier, Mount Stephen, and Kicking Horse Pass, as well as several unnamed mountain views.

In 1893 Brymner’s paintings of Lake Louise and Lake Agnes were shown in the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts exhibition in Montreal and at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The critical response these works received in Montreal is striking: commenting on Lake Agnes, c.1893, a critic for the Herald declared that “there is a grandeur about this pictuer [sic] which commands attention at once, while a closer inspection reveals deep melody of tone, which is delightful.”

Reviews like this one demonstrate that even if Brymner’s primary motivation for visiting the Rocky Mountains to create works for the CPR was financial, the resulting paintings were important to his reputation as an artist because critics reviewed them and assessed them as representations of Brymner’s talents. Today these landscapes illustrate how Brymner deployed his skills in the service of nation building in Western Canada.

The “Real” Quebec

Brymner painted many works depicting rural communities and landscapes in Quebec. He presented his wealthy urban audiences with a pastoral vision of rural French-Canadian traditions, and this vision had powerful connotations. The figure of the “habitant” was perceived as distinctly Canadian and was part of an emerging national identity represented in art, literature, and even music. Brymner and several of his peers would contribute to this discourse through paintings; for instance, Maurice Cullen (1866–1934) painted several Quebec winter scenes, most notably Logging in Winter, Beaupré, 1896, and Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté (1869–1937) created several works depicting rural scenes in Arthabaska, his home region. Paintings of rural Quebec invited viewers to reflect on the importance of French-Canadian culture within the nation. At the same time, these works tacitly reminded viewers of the contrast between rural Quebec and the modernity of the city.

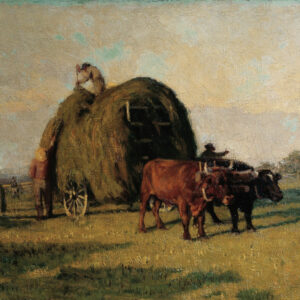

Initially Brymner worked in Baie-Saint-Paul, a place he may have chosen because the region reminded him of the French countryside. Later he made visits to Beaupré and Sainte-Famille, often in the company of other artists, particularly Edmond Dyonnet (1859–1954), Maurice Cullen, and Edmund Morris. He created numerous paintings of rural subjects, such as Evening, Beaupré, 1903, and Haying near Quebec, Beaupré, 1907, and he saw himself as an observer of French-Canadian rural communities. Although by this point Brymner was highly critical of the Barbizon school (and of any stylistic imitation), he did admire Jean-François Millet (1814–1875), a Barbizon painter who was known for his depictions of labourers, and these works may have inspired Brymner’s rural Quebec paintings. These are sites in the traditional territories of the Huron-Wendat, the Haudenosaunee, and the Wabanaki Confederacy Peoples, but Brymner does not appear to have recognized or reflected on the significance of the Indigenous inhabitants of this region.

In writing about Sainte-Famille, Brymner commented, “As no outsider had ever stayed there, to my knowledge, I determined that I would, and paint some real habitants.” Brymner was not the first artist to visit the region (for instance, Horatio Walker [1858–1938] travelled there in 1877, and he also became known for his paintings of the region), but he undoubtedly was an outsider. Based in Montreal, a city experiencing significant industrial growth, Brymner was not wealthy, but he had numerous connections to the city’s elite; in addition, he was Anglophone and Protestant. Still, he took a deep interest in the French-Canadian community he was living among in Sainte-Famille and published some of his musings in the University Magazine, in which he depicted the people as markedly removed from modern life. For instance, in describing his friendship with Michel Marquis, the local workman in whose home Brymner was boarding, he noted that Marquis was talented in woodwork, but that “most of the simplest things outside his own parish he knows nothing about.” Brymner’s sense of superiority is evident.

Brymner’s Quebec paintings, such as Early Moonrise in September, 1899, represented agricultural landscapes and people at work, as if to celebrate a timeless pastoral community. Some works, such as The Weaver (La Femme au métier), 1885, focus on the individual, while others, such as La Vallée Saint-François, Île d’Orléans, 1903, place figures at a distance. Critics recognized the people in these paintings as representatives of a distinct culture, one uniquely Canadian. For example, in 1906, the Montreal Daily Star claimed Brymner had a gift for representing “a typical scene down the lower St. Lawrence, and besides conveying the charm of the fresh unspoilt day, [his work] suggests the patient, submissive lives of the French-Canadians.” The tone of this review underscores the significance of Brymner’s work in rural Quebec. He was not simply painting in a particular place, he was creating paintings that connoted cultural difference. In doing so, he was contributing to a wider discourse about the position of French Canadians in Canada.

A Canadian Artist in International Exhibitions

Through his participation in international exhibitions, Brymner was identified as a representative of Canadian art in a global arena. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the success of Canadian art on an international stage was seen as indicative of the growth and strength of Canadian art and of Canada as a nation. Artworks created by Brymner and his contemporaries have sometimes been viewed as reliant on European art (both during their own lifetimes and in later analyses). In some respects this assessment is fair: these were artists who had not only trained in Europe but were often inspired by European styles, from the French academic tradition to Impressionism. At the same time, these artists were invested in ensuring that Canada became part of the international art community. For them, a distinctly Canadian style for art was important, but so was the space in which they would show it to the world.

Displays of Canadian art at international exhibitions were seen as statements not simply about Canadian artists, but as affirmations about Canada as a new nation. At the Colonial and Indian Exhibition, an event designed to demonstrate the strength of the British Empire (especially the Empire in India), Brymner’s A Wreath of Flowers, 1884, and Crazy Patchwork, 1886, were on view in the Canadian art section. This display received significant critical attention. One English writer claimed that “while walking among the Canadian pictures . . ., you can fancy yourself in a good European gallery much more easily than you can if you are in the Fine Art section of any other Colony.” This comment was intended as high praise. In his assessment, the British painter John Hodgson (1831–1895), who particularly admired Crazy Patchwork, specifically linked the display to colonial power and imperialist ambitions to spread “the blessings of civilization,” declaring, “I make it part and parcel of that glorious dream that art shall be practised wherever Britain holds dominion.” As far as Hodgson was concerned, art was part of Canada’s colonial project, whether or not it made direct reference to colonial settlement.

International recognition was important to Canadian critics. In coverage of the awards at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, the Montreal Herald reported, “Canada has been successful beyond the fondest expectations,” and noted that “sunny Italy, known as the birth place of fine art, exhibited 192 works of the old and modern school, and was awarded only ten diplomas and medals, while Canada, a new country, captured five out of 113.” The medal recipients included Robert Harris (1849–1919), who had led the committee to organize the Canadian display, and George Agnew Reid (1860–1947). The Herald’s account indicates that these medals were more than individual achievements: international praise for Canadian art was a serious matter of national pride, and this continued to be the case in the early 1900s.

In 1910 the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts organized an exhibition of Canadian art in Britain. Brymner was president of the RCA at the time, and his contributions included Under the Apple Tree (À l’ombre du pommier), 1903, and Miss Dorothy and Miss Irene Vaughan, 1910. The exhibition was a success, and Montreal’s Gazette reprinted praise from British papers. The Morning Post had optimistically suggested that Canadian art might be at “the beginning of a movement that will produce great things in future,” and the Times had claimed, “In any future history of modern art, the Canadian section must occupy a conspicuous place.” Although British reviews also included criticism, these compliments were important.

While the vast majority of exhibitions that Brymner participated in were held in Canada, showing his work internationally mattered deeply to him. He occasionally exhibited in Britain during the early part of his career, and he was interested in the possibility of submitting work to the Royal Academy of Arts in London. He was delighted when Border of the Forest of Fontainebleau, 1885, was accepted for the Paris Salon exhibition. Later international exhibitions were milestones in Brymner’s career: at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo (1901), where his exhibited works included The Grey Girl, 1897, and Francie, 1896, he won a gold medal; while at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis (1904), his exhibited works included Early Moonrise in September, 1899, and Under the Apple Tree, and he received a silver (neither medal appears to have been awarded for specific works). Brymner’s participation in these exhibitions was integral to his reputation as a leading Canadian painter.

Legacy as a Teacher

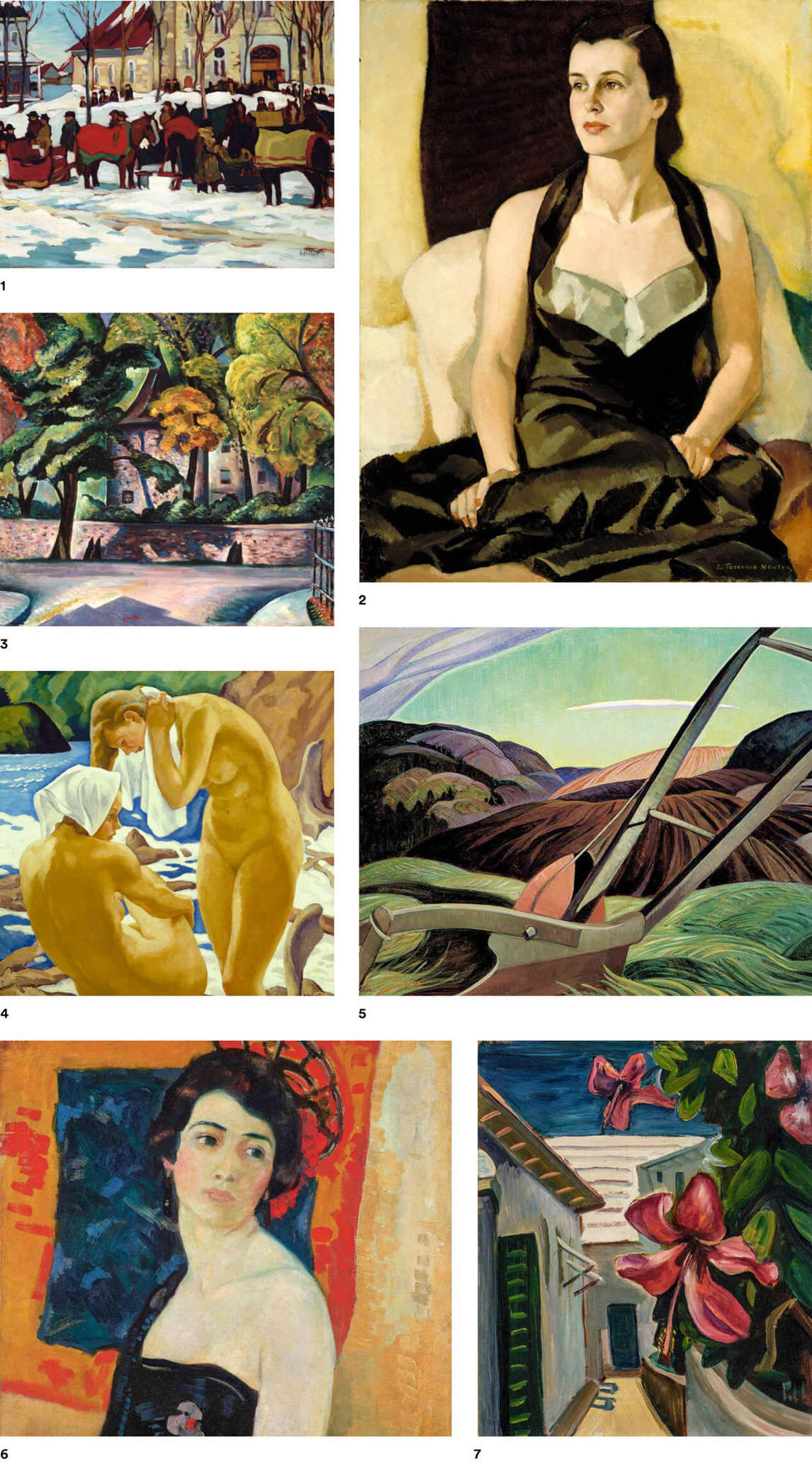

Brymner’s approach to teaching was striking: it was defined by his strong commitment to the French academic tradition, but he also encouraged students to develop their own styles. A consideration of Brymner’s career is incomplete without a discussion of his achievements as an instructor at the Art Association of Montreal. Brymner’s ability to instill confidence was one of his greatest gifts. Although he knew that the majority of his students had no intention of becoming professional artists, many of them did make important contributions to modern art in Canada. His students included artists such as Kathleen Morris (1893–1986), Emily Coonan (1885–1971), Edwin Holgate (1892–1977), Lilias Torrance Newton (1896–1980), and Prudence Heward (1896–1947). Each of these artists created paintings that were radically different from Brymner’s own, as can be seen in works like Heward’s Girl on a Hill, 1928. Although Brymner was not an avant-garde painter, throughout his lifetime many believed he was a good one. But to focus on that issue is to miss the more profound point: Brymner did not need to be radical himself to have a radical impact on his students.

Brymner had trained in French art schools, and under his tenure he ensured that the AAM offered a program based on the French academic tradition. His approach to teaching was likely inspired by that of one of his own teachers, Tony Robert-Fleury (1837–1911). Brymner’s practice was to advise his students only, almost never touching their works. Recalling a lesson from Brymner in November 1905, Randolph Hewton (1888–1960) noted, “I did nothing but draw in the head and Brymner did nothing but talk.” In its emphasis on draftsmanship and the study of the human figure, Brymner’s curriculum was conservative in many respects, and many of his students’ drawings are classic academic studies. Yet despite this attachment to tradition, Brymner believed strongly that his students should be individuals, and he urged them to pursue new directions in their work. He often supported and mentored them long after they had left the AAM—he encouraged them to travel, as he himself had, and to explore art abroad, especially in Europe.

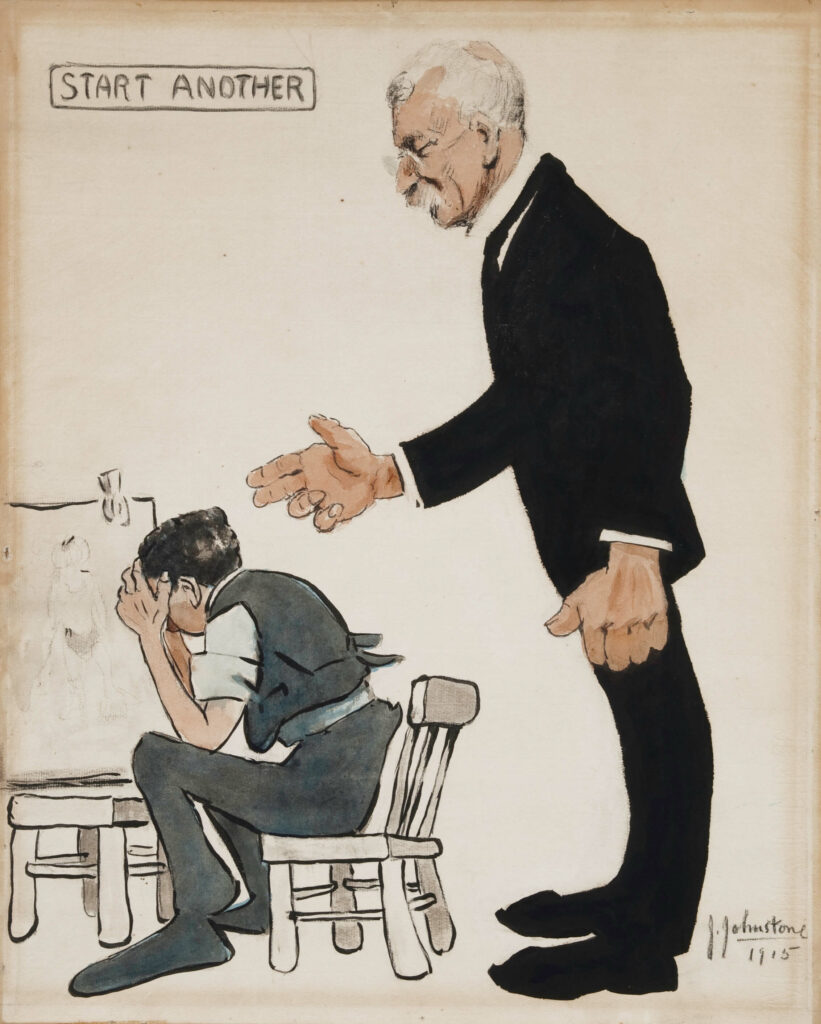

Brymner was remembered by his students as a teacher who was demanding but inspiring. A caricature by John Young Johnstone (1887–1930) suggests how Brymner pushed his students to excellence by repeatedly advising them to start over. The method was effective: according to Clarence Gagnon (1881–1942), “If Brymner couldn’t teach you, nobody could.” More importantly, Brymner allowed for flexibility. Anne Savage (1896–1971) claimed that “he possessed that rare gift in a teacher—never to impose his own way on his pupils. . . . Consequently from a small neucleous [sic] individuals of different types were able to develop their own mode of expression.” He wanted his students to develop confidence. At a 1979 retrospective, Corinne Dupuis-Maillet (1895–1990) spoke of Brymner affectionately, commenting: “He had a knack of making you feel you were the best of all. He gave us incentive. I’m still going on that energy.” The radical stylistic experiments that some of Brymner’s former students made are the best evidence of how successful Brymner was at encouraging individuality. In Hewton’s Après-Midi Camaret, c.1913, for instance, the former student represents a female nude in a landscape with strong, stylized colours, an approach clearly inspired by Post-Impressionism. It was a bold choice for a young artist who had trained in the academic tradition, but it was one Brymner supported.

A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974) knew Brymner, and in an assessment of Brymner’s career, he noted that Brymner “encouraged his students to be independent” and “among his fellow Academicians he would stand for no intolerance or injustice toward the younger artists.” Jackson concluded: “Of all the artists I knew as a student, there was no one I admired more. . . . He was not a very good painter, but he was a great individual, much respected by James Morrice and Maurice Cullen, and the young artists in Montreal.” Jackson was not alone in seeing Brymner’s leadership as transformative for Canadian art. Arthur Lismer (1885–1969), when he was commenting on modern painting in Montreal in 1934, speculated that “this independence can be traced to William Brymner who was a fine artist and a great teacher . . . Toronto has not been so fortunate.” Brymner’s students had become leaders and trailblazers in the arts, participating in the Beaver Hall Group, the Contemporary Arts Society, and the Canadian Group of Painters. Through their works, Brymner’s influence would ripple through Canadian art for decades after his death.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements