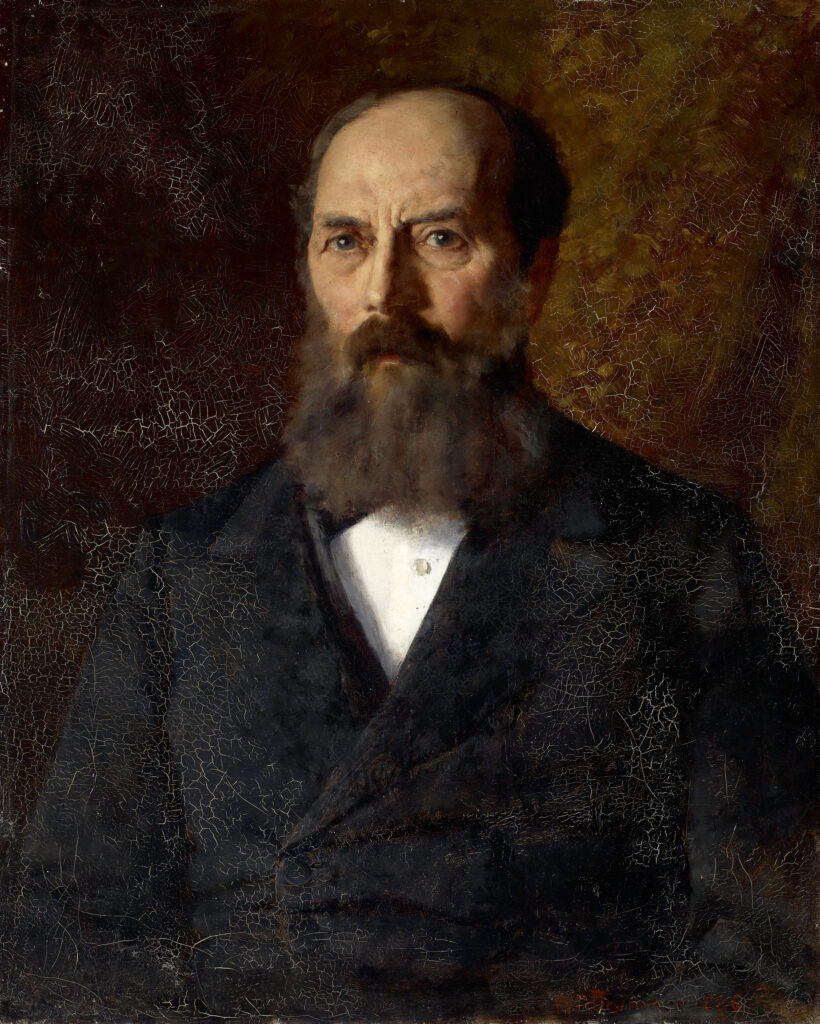

A man ahead of his time, William Brymner (1855–1925) is the father of modern Canadian painting. A.Y. Jackson and Arthur Lismer credited him with transforming art in Montreal, and the Canadian Impressionist movement and the Beaver Hall Group would not have taken root without Brymner’s influence. Just as Canada was establishing itself as a nation, Brymner played an important role as an esteemed educator whose students included luminaries such as Helen McNicoll, Edwin Holgate, Clarence Gagnon, Prudence Heward, and Anne Savage. An adventurous artist and an inveterate traveller, both in Europe and within Canada, Brymner sought new subject matter constantly. At the height of his career, he was widely recognized as an artistic leader in Canada.

Childhood and Early Work

William Brymner was born in Greenock, Scotland, in 1855. He was the eldest child of Douglas Brymner and Jean Thomson, who immigrated to Canada in 1857. Although Brymner spent nearly all his childhood and most of his adult life in Canada, his Scottish background remained a key part of his identity. On visiting Scotland in 1878, he reported, “My native air seems to agree with me because I never felt better in my life.” His friends and colleagues in Canada also thought of him as Scottish. In his recollections of Brymner, the art dealer William R. Watson noted that Brymner had never lost the Scottish accent he had acquired from his parents. When Brymner died, an obituary described him as “tall and slender and typically Scottish in type.”

Little is known about Brymner’s childhood, but the letters he wrote in later life indicate that he was close to his relatives, especially his parents. The family initially lived in Melbourne, Quebec, and Brymner attended St. Francis College in Richmond, Quebec. They moved to Montreal in 1864. As a teenager Brymner was interested in drawing and design, and in 1868, while still in school, he began taking night classes at the Conseil des arts et manufactures de la province de Québec, a school that offered drawing classes to promote industrial design. Brymner’s parents were supportive of his interests, and in 1870, when he finished school, his father arranged for him to study with the architect Richard Cunningham Windeyer (1831–1900). At this point Brymner’s goal was to become an architect (it would be almost a decade before he decided against this career path). Unfortunately, he was too young to work in Windeyer’s office—he was “so diminutive of stature that he had to stand on a bench to get his elbows above the drawing board.” Eventually Brymner left to study French at Sainte-Thérèse seminary.

In 1872 the Brymner family moved to Ottawa because the Canadian government offered Douglas Brymner the position of clerk in charge of the archives of Canada. It was only five years since the British North America Act had united Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick through Confederation, making Canada a dominion within the British Empire. As a country with a new national identity, Canada had no official archives. Douglas’s first task was to establish them, and he quickly began seeking out records. He may have used the connections he made in this work to help his son obtain a job in the office of Thomas Seaton Scott (1826–1895), the chief architect of the Department of Public Works—one of the many occasions when his support would prove critical for his son. Though Brymner is not known to have designed any buildings for the department while working there, in 1876 he visited Quebec City (possibly at Scott’s request) and made a series of drawings of its fortifications and streets. These drawings, which include Mountain Hill Looking Up and Palace Hill, demonstrate his early efforts to master perspective and depict urban space.

Brymner grew up a pleasant but serious young man. In a letter to his brother, Douglas reported that his son was saving to study at the Royal Academy of Arts in London and commented, “It is a great blessing he is so steady and associates only with very steady fellows so that we never have the slightest uneasiness about him.” Despite this proud claim, Brymner’s parents may have been unsure about their son’s plans. Opportunities in art and design in Canada were limited at this time. Many arts organizations were still very young and small; the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts would not be founded until 1880. As well, many patrons still looked to Europe and its buildings and art collections as the standards to emulate in Canada. Thus, many aspiring artists in Canada concluded that going abroad was necessary—a critical investment in a future career. They believed Europe was the ideal place to learn: for instance, Robert Harris (1849–1919), a Canadian artist in Paris in 1877, reported that the atelier he was studying in was “perhaps the best in Paris, which means the world.” Brymner undoubtedly shared this view. Although training in Europe was expensive, in the winter of 1878 he sailed for Britain, where he visited relatives in Scotland before moving to Paris.

Paris Studies

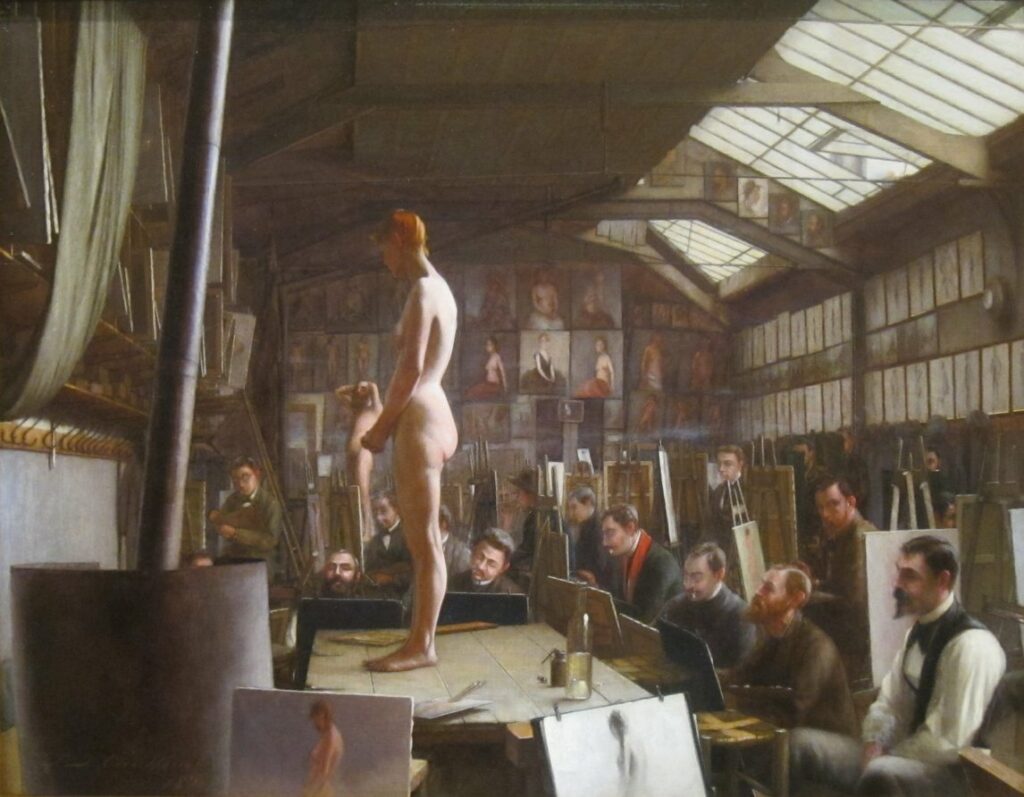

In March 1878 Brymner arrived in Paris intending to study art and design—he was still considering becoming an architect. The city offered unequalled access to artworks, from paintings by Old Masters in the Louvre to exhibitions elsewhere of works by contemporary French artists, from academic painters to the Impressionists he took an interest in later in his life. Paris was also home to a vibrant community of expatriate art students drawn to the city’s art schools that offered programs based on the curriculum at the École des beaux-arts. Students began by drawing casts, often of antique statues, before progressing to drawing living models and, finally, to painting. This approach to artistic training was promoted through the École, but that school was difficult to get into because it offered limited spaces to non-French students and admission required passing challenging examinations. Many international students, Brymner included, found themselves attending alternative schools and directing their own studies.

When Brymner arrived in Paris he found a job working for the Canadian section of the Paris Exposition, assisting with the creation of displays. Like other world’s fairs, the exposition showcased an enormous range of objects, with a special focus on natural resources and manufactured goods. It also served as a presentation of European colonial power, a reflection of European dominance in global politics. (The Canadian exhibits were within the section allotted to the British Empire.) For Brymner the exposition meant working long hours for a much-needed salary, but he still had the time to explore other countries’ displays, noting, “[It’s] worthwhile walking about to see the different ways of work and kinds of tools used by the Russians, Chinamen, Dutchmen and Spaniards.” But Brymner had come to Paris to study art, and he had already begun taking night classes in drawing at the École gratuite de dessin.

In July 1878 Brymner’s job with the exposition ended and he had more time to devote to his art studies. He started additional drawing lessons with a new teacher, and then, in October, he enrolled at the Académie Julian. There his teachers included the renowned French painters Jules-Joseph Lefebvre (1836–1911), Gustave Boulanger (1824–1888), Tony Robert-Fleury (1837–1911), and William Bouguereau (1825–1905), artists known for their skills in depicting human bodies. Brymner’s program at the Académie resembled the traditional progression at the École des beaux-arts. Drawing was the central focus, and he was initially sketching plaster casts. He began working from live models in early January 1879.

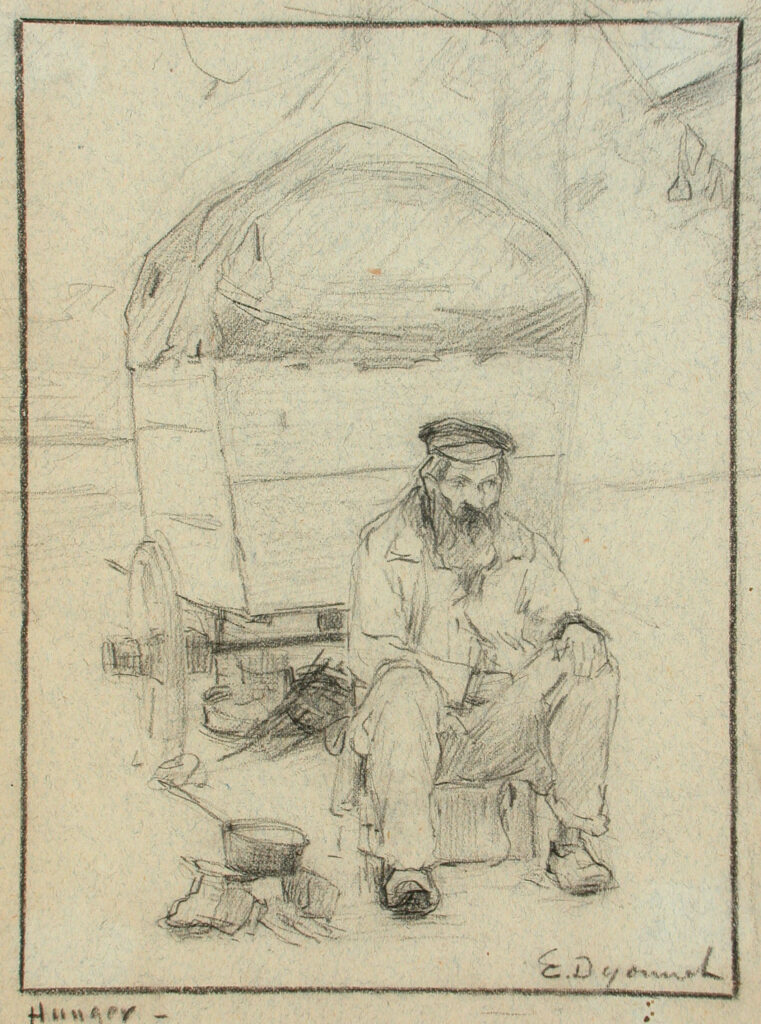

Throughout his studies, Brymner wrote long letters to his parents in which he provided numerous details of his work, as well as of his worries. He repeatedly explained the costs he faced. Determined to show that he was careful with money, he reduced his expenses to the point of going hungry often; in retrospect, he felt that this deprivation affected his focus on his work. He was also homesick. Thirty years later he told a friend: “I remember the feeling of never getting enough letters from home. . . . After a while unfortunately you begin not to care so much & then perhaps not at all. I have never reached that stage yet & hope I never will.”

Although Brymner fretted about his abilities, his correspondence suggests he was a focused and disciplined student. He especially admired Robert-Fleury’s approach to teaching, reporting, “I like his ways of correcting exceedingly. . . . He does not put a line on the paper or at least very seldom, but the way he picks things to pieces is astonishing.” Robert-Fleury was an encouraging teacher, and when he noticed that Brymner appeared to be forcing himself to draw, he advised a break, declaring, “il faut vous amuser en dessinant” (you need to have fun drawing).

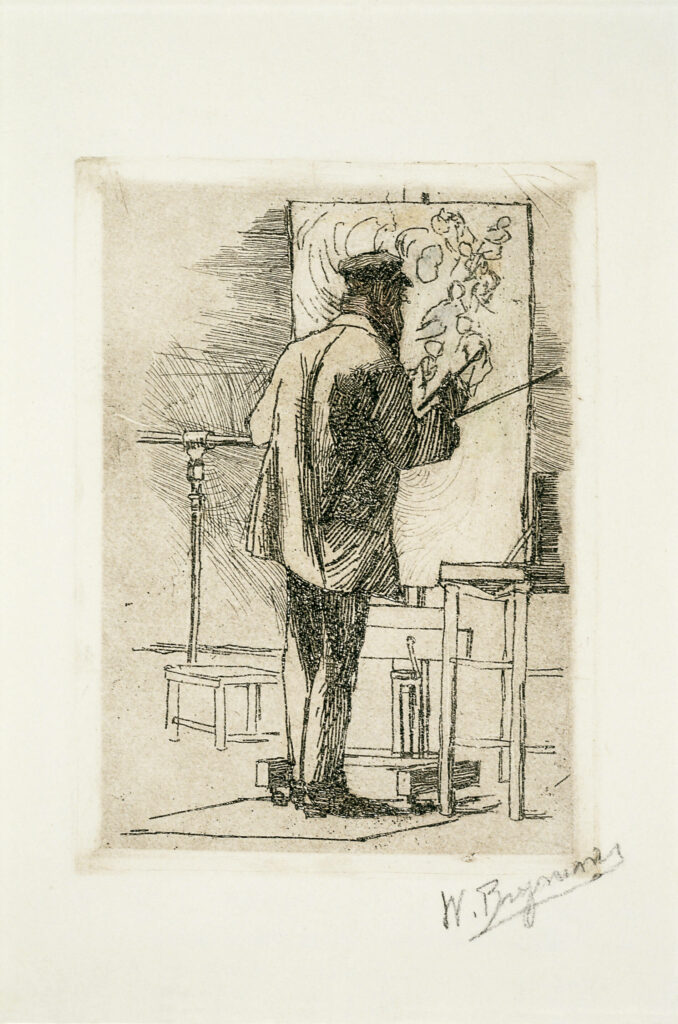

Brymner sought out learning opportunities in the city. He visited many well-known sites in Paris and beyond, exploring randomly chosen locales in the French countryside and sketching the places he saw. Like many other art students in the city, he also studied by copying works in the Louvre, an experience he later depicted in an etching.

It was while he was in Europe that Brymner definitively decided to become a painter. In February 1879 he told his father that he had “given up all idea of being an Architect” and that he was “exerting [himself] altogether in the direction of painting.” A year later he declared: “I must stay another year. I have now no doubt of going through with what I started with such fear and trembling.” He was not only determined to become an artist, he was also determined to avoid teaching art, telling his mother, “I hope from the bottom of my heart never to need to become Master at any art school.” In 1880, however, financial necessity forced him to return to Canada, and to take up teaching.

The Ambitious Artist

Although Brymner’s Self Portrait of 1881, a drawing made after he came home to Ottawa, shows a confident young man, he had only just begun to establish a career. He had hoped to avoid becoming a teacher but he still needed an income, so, as a temporary solution, he took a position at the Ottawa Art School. In the summer of 1881 Brymner returned to Paris with the intention of formally resuming his studies, but he became seriously ill with rheumatic fever and returned to Ottawa that fall. By the spring he had recovered, and he accepted a commission to create illustrations for the writer Joshua Fraser’s book Shanty, Forest and River Life in the Backwoods of Canada (1883), most likely because he needed money. He went back to the Ottawa Art School that fall, but he stayed only through the spring.

Brymner returned to Europe in the summer of 1883. He spent time painting in Burgundy with the British artist Frederick Brown (1851–1941) and he returned to Paris, resuming his work at the Académie Julian. He felt there were several advantages to being in Europe. In a letter to his mother, he noted that “models are so much cheaper and more easily got than in Canada.” To his father, he explained, “I would very much rather do my summer’s work on this side with some others, who can paint than go out and work by myself in Canada. I think it would be easier to sell work done here too.” He was also interested in keeping up with European art. In the winter of 1884 Brymner visited the Édouard Manet (1832–1883) memorial exhibition at the École des beaux-arts, an experience he would recall later in life. He admired Manet for painting en plein air, and believed that his late works, such as A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1882, would be long remembered.

In the spring of 1884 Brymner made plans to go to Yorkshire with the British artist Frederick W. Jackson (1859–1918) and Scottish-Canadian artist James Kerr-Lawson (1862–1939), both of whom were also working in Paris that winter. The group elected to stay in Runswick Bay, where Brymner completed a critical group of paintings. These include A Wreath of Flowers, 1884, a large and complex work that eventually became his diploma submission for the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, and The Lonely Orphans Taken to Her Heart, 1884, as well as smaller works.

Brymner was artistically productive in England, but he still worried about money and the feasibility of being a painter. His father was trying to sell his son’s works in Canada but had limited success, and Brymner stated that he did not have “the same courage to go on painting” when they failed to sell. After several months in Yorkshire, he returned to his studies in Paris in January 1885. He again enrolled part-time at the Académie Julian, believing that it should be his last winter there, because “what more I do must be done for myself. But I think it important that I should have this last turn.” He also wanted to create a work that would improve his reputation as an artist, and in this he was successful. Border of the Forest of Fontainebleau, 1885, a landscape painting inspired by the Barbizon school, was accepted for exhibition at the Paris Salon. For Brymner, this was a major achievement.

Inclusion in the salon was prestigious but not financially rewarding, and Brymner returned to Canada. He spent the summer of 1885 in Baie-Saint-Paul in the Lower Saint Lawrence region of Quebec, a location he may have chosen because he believed it resembled the French countryside. At Baie-Saint-Paul he continued to work on subjects similar to those he had painted in Europe, such as children playing outdoors. Four Girls in a Meadow, Baie-Saint-Paul, 1885, and The Books They Loved They Read in Running Brooks (Ils aimaient à lire dans les ruisseaux fuyants), 1885, were among his earliest oil paintings depicting rural Quebec, a subject he would return to many times throughout his career. He would eventually become known for his depictions of French-Canadian landscapes and people. In 1885, however, his Baie-Saint-Paul works suggested a determination to create thematic continuity in his paintings despite having left Europe.

A year later, Brymner travelled to Western Canada. The Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) had been completed the previous November, and it was a transformative project for the entire country. British Columbia had joined Confederation in 1871 with the agreement that Canada would build a railway connecting it to the provinces in the east—Ontario, Quebec, and the Maritimes. The completion of the railway fulfilled this promise, but it also led the government to encourage mass settlement on the prairies and to force Indigenous peoples onto reserves with increasingly draconian measures.

Brymner would witness all these changes on his trip, which was critical to his future work. It was yet another strategic decision: he was aware that the CPR was commissioning landscapes depicting the Rocky Mountains from artists in Canada and from abroad. For instance, John Arthur Fraser (1838–1898) had received a commission for watercolours; one of the works he created was Summit Lake near Lenchoile, Bow River, Canadian Pacific Railway, 1886. To demonstrate his abilities, Brymner, while staying near Rogers Pass, began a painting that was five feet in length, one “intended to beat this Aitkins [sic], who comes out from Glasgow to paint the Rockies for the C.P.R.” He clearly knew that the Scottish artist James Alfred Aitken (1846–1897) was working for the railway. Painting on such a large scale was a challenge, and only a few days later he reported, “A 5 foot picture is no joke.” He wrote no more about this painting, which he may not have finished. Later in his career, however, Brymner would paint other views of the mountains.

Brymner’s 1886 trip was also significant because he spent weeks visiting the Siksika Nation Reserve near Gleichen (now in Alberta). Outsiders were not usually permitted to live on the reserve, but the local Indian agent, Magnus Begg, permitted him to do so for a few weeks. It is unclear why this exception was made (or even why Brymner wished to stay there). Brymner thought Begg had made the decision on his own authority and he worried that it might be unwise to ask federal authorities in Ottawa for official permission. While there, Brymner completed one of the most striking works of his career. Giving Out Rations to the Blackfoot Indians, NWT, 1886, is a haunting image of government food rations being distributed to the Siksika People. Brymner’s time on the reserve had a limited impact on his work overall, but his memories of the visit remained vivid more than twenty years later when he recounted them in detail in a long letter to a friend, the artist Edmund Morris (1871–1913).

Cultivating his reputation as an artist was challenging, but ultimately the years between 1882 and 1886 were some of the most productive of Brymner’s career. He had created several large oil paintings, such as Border of the Forest of Fontainebleau, with which he established himself as a professional artist. Not only was Brymner regularly submitting his work to exhibitions, but in 1886 he became a full member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts. That same year, his paintings A Wreath of Flowers and Crazy Patchwork, 1886, were selected for the Colonial and Indian Exhibition in London, a massive event intended to celebrate the British Empire, especially Britain’s imperial possessions in India. These were notable achievements for a young artist in Canada, but they did not bring significant financial success. Money remained a major concern.

The Ambivalent Art Teacher

In the fall of 1886 Brymner accepted a job as master of the School at the Art Association of Montreal (AAM). He would go on to teach at AAM for over thirty years, but at the time he was ambivalent about teaching and had ambitions to advance his own artwork. Writing to his father in March 1889, he reported that he had not sold any paintings recently and so he planned to keep his teaching job for the following school year: “I feel as if it would be too much of a risk to throw up the School which is a certainty, for such very vague chances as I see ahead at present.” Brymner would not leave his position at AAM until 1921, but the fact that he was considering it in 1889 demonstrates that he was still determined to work on his own paintings.

Brymner’s predecessor, Robert Harris, had been appointed director and principal instructor of AAM in 1883. Harris had also studied in Paris, and he developed a program at AAM that emulated the French academic tradition: students began by mastering the drawing of casts before they progressed to life drawing. Brymner continued this system but gradually made additions to the classes the school offered, including outdoor sketching (1889) and elementary drawing (1898).

Brymner also occasionally gave special lectures, including a presentation on Impressionism in which he offered an assessment of the artistic movement, as well as of artistic styles in general. He was highly critical of anyone who aspired to work in a specific style, declaring: “You see a great deal written about men who are classics and men who are naturalists and others Romanticists, and so on. . . . There are really only two kinds of painters. Those who show us what they sincerely see and feel, and those who are the followers of someone else.” His thinking around the formation of stylistic “schools of art” was that they represented a point at which “individuality is lost, and conventionality begins.” Brymner’s conviction that an artist should not try to emulate a particular style was critical to his own oeuvre. In the same spirit, encouraging individuality was a principle of his advice to students.

Brymner’s teaching position at AAM afforded him a stable income and professional position, and his own artistic practice during this period was defined by a voracious thirst for travel. He travelled back to Paris in the summer of 1889, returning to the Académie Julian and visiting the Exposition Universelle. Though this exposition is particularly famous because the Eiffel Tower was built for it, Brymner was more interested in the art. He thought there had never before been “so good a chance to study what is being done in the way of pictures all over the world. The collection is enormous and well arranged; not only are the pictures of each Country kept together, but each man’s work is kept as much as possible by itself.” Brymner was always curious about the work of other artists and valued this opportunity, but he did not leave a record of the artists to whose work he was most drawn.

Travelling in the summer became part of Brymner’s annual routine despite the modest salary he earned at AAM. In 1891 he spent time working in Killarney, Ireland, meeting up with friends such as the artist James M. Barnsley (1861–1929). Visiting the Netherlands and Belgium later that summer, he went to Amsterdam, Haarlem, and Antwerp to see paintings by Rembrandt Haarmenszoon van Rijn (1606–1669), Frans Hals (c.1582–1666), and Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640). Brymner admired Rubens’s works most of all, declaring that the artist did “everything as naturally as the bird flies”—he described Rembrandt as laboured in his work and Hals as lacking in Rubens’s range. In addition to giving him the opportunity to see more artworks first-hand, Brymner’s European travels were critical to his professional standing because many Montreal collectors valued Old Masters and modern European paintings above all other art. Thus, to understand these works was not only an opportunity to better understand Western art history, it was also an opportunity to better understand the tastes of his potential patrons in Montreal.

Not all of Brymner’s trips were to Europe, however. In 1892 the Canadian Pacific Railway sponsored Brymner’s travel to Western Canada, and he returned there in 1893. Under the direction of William Van Horne, its influential general manager, the company funded many artists’ journeys during this period, with the intention of commissioning artworks that depicted the Rocky Mountains. Though Brymner had painted on an earlier trip west, the 1892 journey was his opportunity to create a large series and to participate in the company’s tremendous artistic project to represent the Rockies as landscapes that were integral to Canadian national identity—while simultaneously celebrating the company’s own achievement in completing the railway. The drawings and painted studies Brymner made on these trips became significant source material for many future artworks.

By the late 1890s Brymner was spending more time visiting the Lower Saint Lawrence region; he went to Beaupré in 1896 and 1897. In 1897 he also visited Paris and Belgium. Taken together, these travels demonstrate a massive commitment to art studies and to searching for new subject matter. They were also crucial to his professional position in Montreal. Both the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts and the AAM held annual exhibitions, and Brymner contributed to their shows almost every year, submitting several works with travel-inspired subjects. The most prominent of these was In County Cork, Ireland (exhibited at both the RCA and AAM in 1892). He also held exhibitions in private galleries, sometimes advertised with reference to his recent trips, such as summer travels in France, Holland, or Quebec.

In addition to his extensive explorations, Brymner sought out further artistic opportunities in Montreal. He was a member of the Pen and Pencil Club, formed to bring together Montreal’s artists and writers. The organization regularly held meetings in which members were asked to share ideas about a specified theme, offering either a sketch or a brief text. Many of Brymner’s contributions survive in the club’s scrapbook. He undoubtedly valued the social environment of the club, and he was responsible for introducing some of his friends as new members, including the artists Edmond Dyonnet (1859–1954) and Maurice Cullen (1866–1934). By the turn of the century, both of these professional friendships had become important to his artistic practice.

A Network of Friendships

In the early 1900s Brymner’s dual career as artist and teacher was well established. He was still teaching at the Art Association of Montreal: his students during this period included William Henry Clapp (1879–1954), Clarence Gagnon (1881–1942), Kathleen Moir Morris (1893–1986), Emily Coonan (1885–1971), and Randolph Hewton (1888–1960). He was regularly participating in exhibitions at the AAM and the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, and he was showing his work in international exhibitions.

Above all, he was becoming well connected. He had long been sociable, and by now he had developed close friendships that were vital to his artistic practice. Brymner continued to travel during the summers, often with other artists. Between 1896 and 1903 he visited Beaupré almost every summer, frequently spending time with Maurice Cullen, Edmond Dyonnet, and Edmund Morris; James Wilson Morrice (1865–1924) was there in the summer of 1903. Brymner valued the fellowship of these visits as well as the artistic opportunities, and the friendships were enduring.

In the early 1900s Brymner returned to Europe. He visited Venice with Cullen and Morrice in 1901 and again in 1902, when they also went to Florence. These European trips gave Brymner an opportunity to better understand Morrice’s work in particular. It was more experimental than Brymner’s own; for instance, Morrice was more interested in the possibilities of expressive brush strokes and of flattening pictorial space. Despite their differences, Brymner later commented that “I like him & like his work & [don’t] know any one who is doing better,” advising Gagnon that “you couldn’t have a better man than Morrice to give you an occasional suggestion.” His travels also enabled Brymner to create works with new European subjects, such as views of Venice, some of which were included in a special exhibition of his and Cullen’s work at the AAM in December 1904.

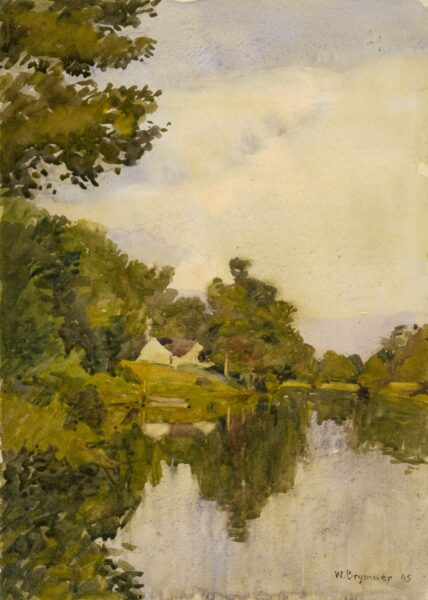

Brymner’s friendship with Cullen was one of the most important of his later career. In addition to travelling and exhibiting together, they shared studio spaces. In the summer of 1905 they built a studio together at Saint-Eustache, a town that was near Montreal but far enough from the city to offer the artists many rural subjects. Brymner painted numerous scenes at Saint-Eustache, in both oil and watercolour. Writing to Gagnon in 1908, he noted that he was there all summer and was “very comfortable” but wished “there was no school to be attended to.”

Brymner’s complaint about the school is revealing. Even after years of exhibitions and significant recognition, he still did not feel financially secure enough to leave his teaching position. Many years later, Group of Seven artist A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974) recalled that “someone said to William Brymner that if artists had more business ability they could make a decent living, to which he retorted, ‘In Canada an artist has to be a financial genius merely to stay alive.’” For Brymner, teaching meant “bread + butter,” and he was conscious of every successful sale. Yet frustration notwithstanding, he was an established artist, and he was on the cusp of his most prestigious achievement.

A Professional Leader

Brymner was elected president of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts in 1909, and he would remain president until 1917. His election is indicative of both his personal interest in the RCA and the leadership role he held in the Canadian art community. He was still committed to exhibiting his own work, and he routinely submitted paintings to the shows organized by the RCA, the Art Association of Montreal, and the Canadian Art Club. He experimented with a wide range of subject matter, including the coast at Louisbourg in Nova Scotia and the female nude. He also continued to teach; among his students in the early 1910s were Edwin Holgate (1892–1977), Lilias Torrance Newton (1896–1980), and Adrien Hébert (1890–1967). Outside these activities, Brymner’s work as president of the RCA raised his profile, and his achievements in this role became central to his legacy.

His presidency was marked by two major special exhibitions of Canadian art. The first, held in 1910, was originally prepared as part of the planned Festival of Empire in London. For Brymner and other Canadian artists, the occasion was a huge opportunity to be part of an exhibition on an international stage. Under Brymner’s leadership, the RCA arranged a selection of 118 works to be sent (the vast majority were oil paintings); artists whose works were shown included Robert Harris, George Agnew Reid (1860–1947), Mary Hiester Reid (1854–1921), Homer Watson (1855–1936), Helen McNicoll (1879–1915), J.E.H. MacDonald (1873–1932), and A.Y. Jackson. Brymner contributed his artworks Miss Dorothy and Miss Irene Vaughan, 1910, October in Canada, by 1910, Under the Apple Tree (À l’ombre du pommier), 1903, and Blackfoot Indian (today known as Blackfoot Chief), c.1888 or 1906. By the time the festival was cancelled owing to the death of Edward VII, the Canadian art was already en route to Britain, in the care of Edmond Dyonnet, whom Brymner had asked to accompany the works. With Brymner’s approval, Dyonnet quickly made alternative arrangements for the art to be shown at the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool, where the exhibit was well attended and well received. Although Canada had been a dominion since 1867, it was still a part of the British Empire, and Canadian artists and critics found the praise from British critics satisfying.

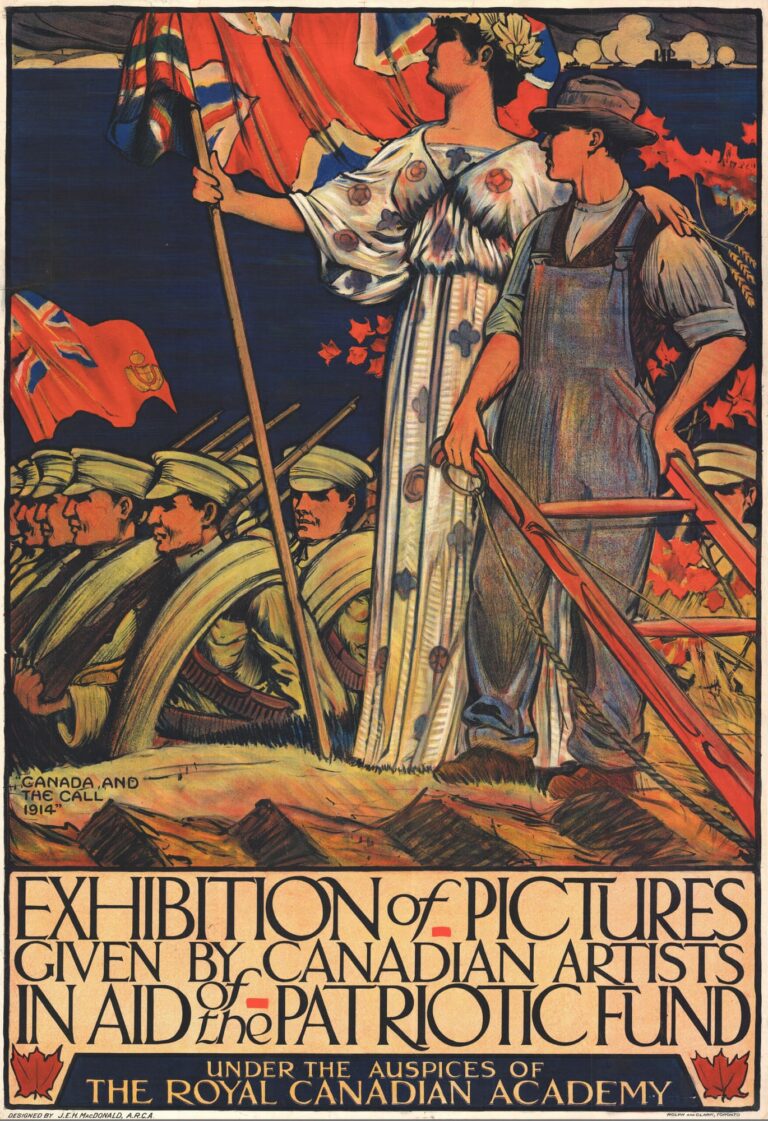

The second major special exhibition that Brymner spearheaded was prompted by the First World War. Like many Canadians, Brymner was horrified by the brutal lists of fatalities and casualties: writing in September 1914 to Eric Brown, the director of the National Gallery of Canada, he noted, “I see by the bulletins this morning that the slaughter in some of the English regiments is fearful.” He was determined to do something to support the war effort. Artists from the RCA, the Ontario Society of Artists, and the Canadian Art Club agreed to work together to arrange a patriotic exhibition. Brymner was chair of the exhibition committee, and the RCA undertook to cover the crucial expenses.

Known as the Exhibition of Pictures Given by Canadian Artists in Aid of the Patriotic Fund, the exhibition toured throughout Canada, going to Toronto, Winnipeg, Halifax, Saint John, Quebec City, Montreal, Ottawa, London, and Hamilton between 1914 and 1915. Artists contributed a wide variety of works; for example, Ozias Leduc (1864–1955) donated Effet gris (neige), 1914, Lawren Harris (1885–1970) donated The Corner Store, 1912, and Emily Coonan donated Girl in Green, 1913. Brymner himself gave a landscape painting entitled Late Afternoon, c.1913 (current whereabouts unknown). In addition to selling these works, the exhibition raised funds through ticket and catalogue sales. It was a financial and critical success and led to Brymner being named a member of the Order of St. Michael and St. George, an honour from King George V that recognized distinguished service in the British Empire. To celebrate, his fellow artists arranged a dinner, and in 1916 a solo exhibition of Brymner’s work was held at the Arts Club of Montreal to mark the pinnacle of an illustrious career.

Final Years

On May 6, 1917, Brymner woke up to find he could not move his left side. He had had a stroke. Brymner spent the next three months at the Royal Victoria Hospital before going to Île d’Orléans to convalesce. Even after he was released from the hospital, he struggled with everyday tasks and later described his recovery as “damned slow. . . . I lay in bed and kept as quiet as possible. I was told I was to behave as much like an oyster as possible.” He returned to Montreal in the early autumn, and on September 12 he married Mary Caroline Massey Larkin. Little is known about Brymner’s relationship with Larkin, but he did tell Clarence Gagnon that he wished he had married her “long before.” Larkin had been on the staff of the Art Association of Montreal, and they had likely known each other for several years at the time of their marriage. Although Brymner’s personal life was happy, his professional life required changes. Edmond Dyonnet had supported him during his recovery and had been invaluable in temporarily managing the affairs of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, but Brymner concluded he could not resume his work as president of the RCA and resigned from his position. It seems unlikely that he was painting during his recovery.

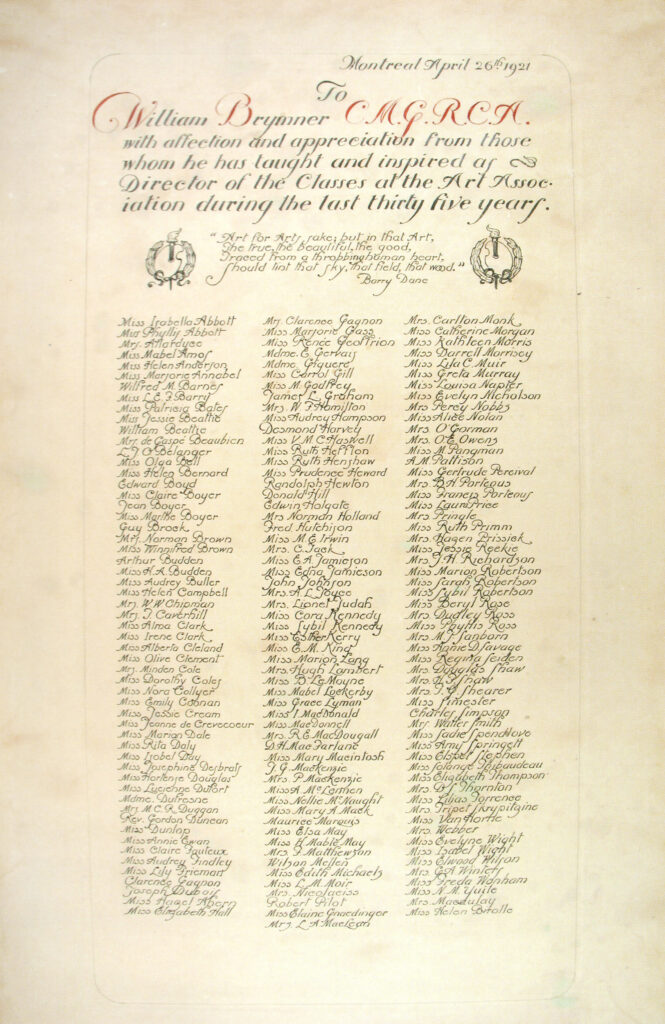

Eventually Brymner was well enough to resume teaching at the AAM, though he walked with a cane. His students in the last few years of his career included Anne Savage (1896–1971), Regina Seiden Goldberg (1897–1991), Prudence Heward (1896–1947), and Robert Pilot (1898–1967). Despite his health struggles, he was still a tremendous teacher, committed to encouraging his students to pursue their own styles. Decades later, Savage would describe him as “a really magnificent man . . . way ahead of his time,” who managed to inspire his students to embrace innovation even though he was “employed by a group of the most conventional people you could imagine.” In 1921, when Brymner finally retired, the AAM held a special afternoon tea in his honour. His students presented him with a celebratory scroll inscribed “with affection and appreciation from those whom he has taught and inspired.” Although he had repeatedly expressed misgivings about teaching to his family and closest friends, Brymner was an immensely gifted teacher. Several of his students not only went on to have noteworthy careers as professional artists, but they also became leaders of modern art in Canada, as key members of the Beaver Hall Group and the Canadian Group of Painters.

On his retirement, Brymner announced that he intended to travel in Europe for three years, particularly France, Spain, and Italy. He stopped submitting to the major exhibitions after he and his wife left Montreal, but he was still painting. Carthusian Monastery, Capri, c.1923, is one of his final works. In June 1925, while visiting some of his wife’s relatives in England, Brymner died. He was honoured with two posthumous exhibitions, one at the Watson Art Galleries in Montreal in late 1925 and one at the AAM in early 1926.

In many ways, Canadian art had moved on by 1925. The Group of Seven and the Beaver Hall Group had both formed in 1920, and the artists of these groups, with their different approaches to modernism, were commanding the attention of the Canadian art world. Brymner was an artist of a different generation: he fiercely supported his students’ interests in modernism, but he had not undertaken radical stylistic experiments himself. Critics commenting on his memorial exhibitions praised him for the sheer range of his work. He worked extensively in oil and in watercolour but, above all, he experimented with an enormous range of subjects, from people on the Siksika Reserve to European villages.

For those critics and for later art historians, the extraordinary variety of Brymner’s works has made his career difficult to summarize. Ultimately, this diversity reflects Brymner’s relentless willingness to experiment. In imparting this enthusiasm to his students—through his work as a teacher and through the example of his own career—Brymner inspired a generation of modernists and ensured his own place in the history of Canadian art.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements