Shuvinai Ashoona’s style and technique have developed and changed over the twenty-five years that she has been drawing, such that her art is unique among Inuit artists working today. With the exception of some printmaking, Shuvinai has remained steadfast in her drawing practice, which brilliantly employs Fineliner pen, pencil, and coloured pencil. She undertakes challenges in format: large, small, vertical, horizontal, and three dimensional. Collectors, curators, and art lovers worldwide appreciate her signature whimsy and fluid line, ambitious colour, and imaginative content.

Monochromatic Drawings

At Kinngait Studios, with its history of carving and printmaking, drawing has become a primary practice among many third-generation Inuit artists. Shuvinai Ashoona, with her unlimited imagination and highly personal style and technique, has been an integral player in this innovation. Like the artists of the two generations that came before her, including Kenojuak Ashevak (1927–2013), Pitseolak Ashoona (c. 1904–1983), and Napachie Pootoogook (1938–2002), Shuvinai received no formal training. She honed her drawing skills by working alongside her elders in the studios at the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative. In this classic apprenticeship system, one learns by observation. There is a back and forth among the less experienced artists, who watch and imitate one another, as well as the more experienced artists, until they find their unique artistic style, eventually becoming mentors themselves.

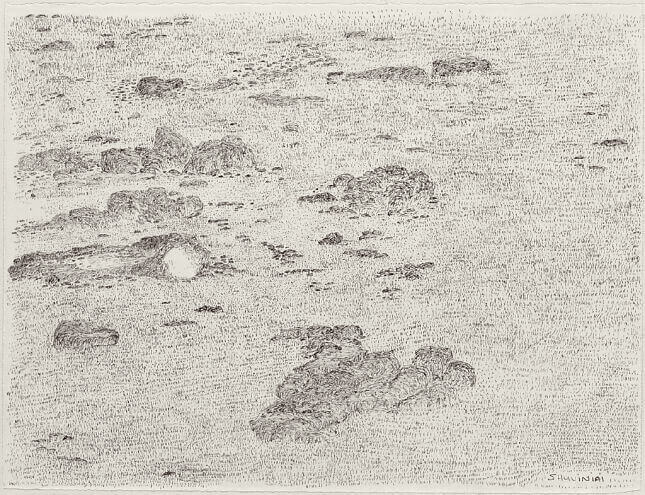

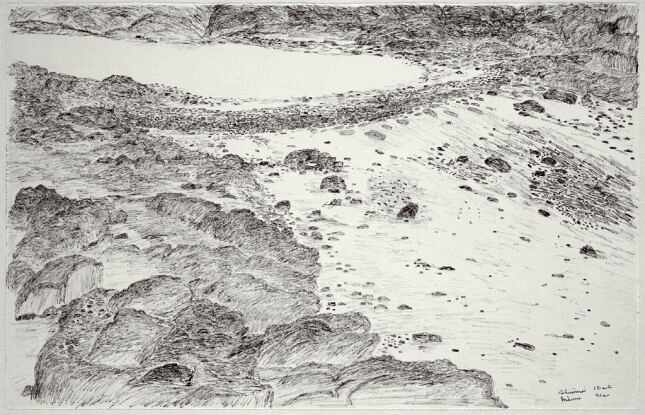

The earliest of Shuvinai’s works purchased by the co-op, dating to 1993, are small black and white drawings of Kinngait that depict the rocky tundra, with scant vegetation, houses, and local landmarks. Delicately and sparsely rendered in scratchy black ink, these landscapes are often portrayed from a bird’s-eye perspective. One of her earliest recorded drawings, Community, 1993–94, shows with specificity structures assembled by the community in relation to the natural environment of Cape Dorset.

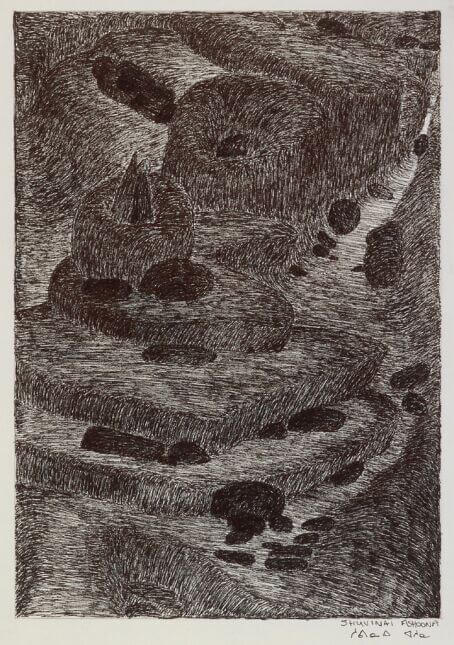

In the late 1990s Shuvinai’s work shifted. The marks she made on the page became more manic and dense, and she began rendering the landscape using hatching to create depth. At this time she began to focus less on Kinngait and her physical surroundings: in surreal landscapes Shuvinai composed images of subterranean mazes, with steps, tunnels, and caves revealing habitat within the levels of landscape. Works such as Rock Landscape, 1998, demonstrate laboured hatching and tiered landscape formations. Such psychologically charged works are much darker than the black and white sketches she made earlier in the decade.

Yet within the period of making these densely rendered drawings, Shuvinai also created images that were less worked and perhaps more playful, integrating human forms and appendages in fantastical vignettes, as can be seen in Discombobulated Woman, 1995–96. As Shuvinai experimented with a wider repertoire of images, she tempered her more imaginary and surreal compositions with ink drawings of place, as can be seen in the later monochromatic work Composition (Tent Surrounded by Rocks), 2004–5.

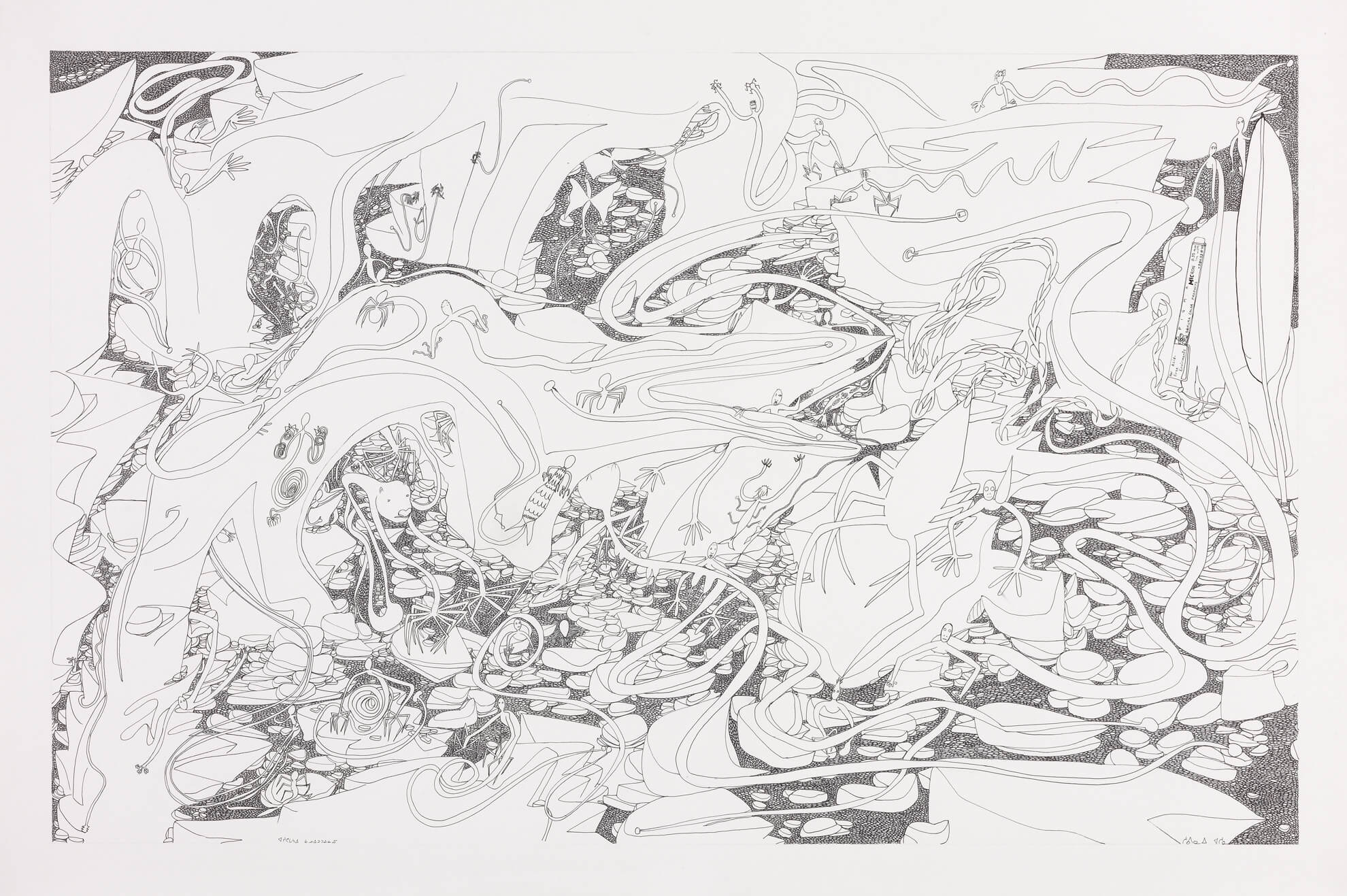

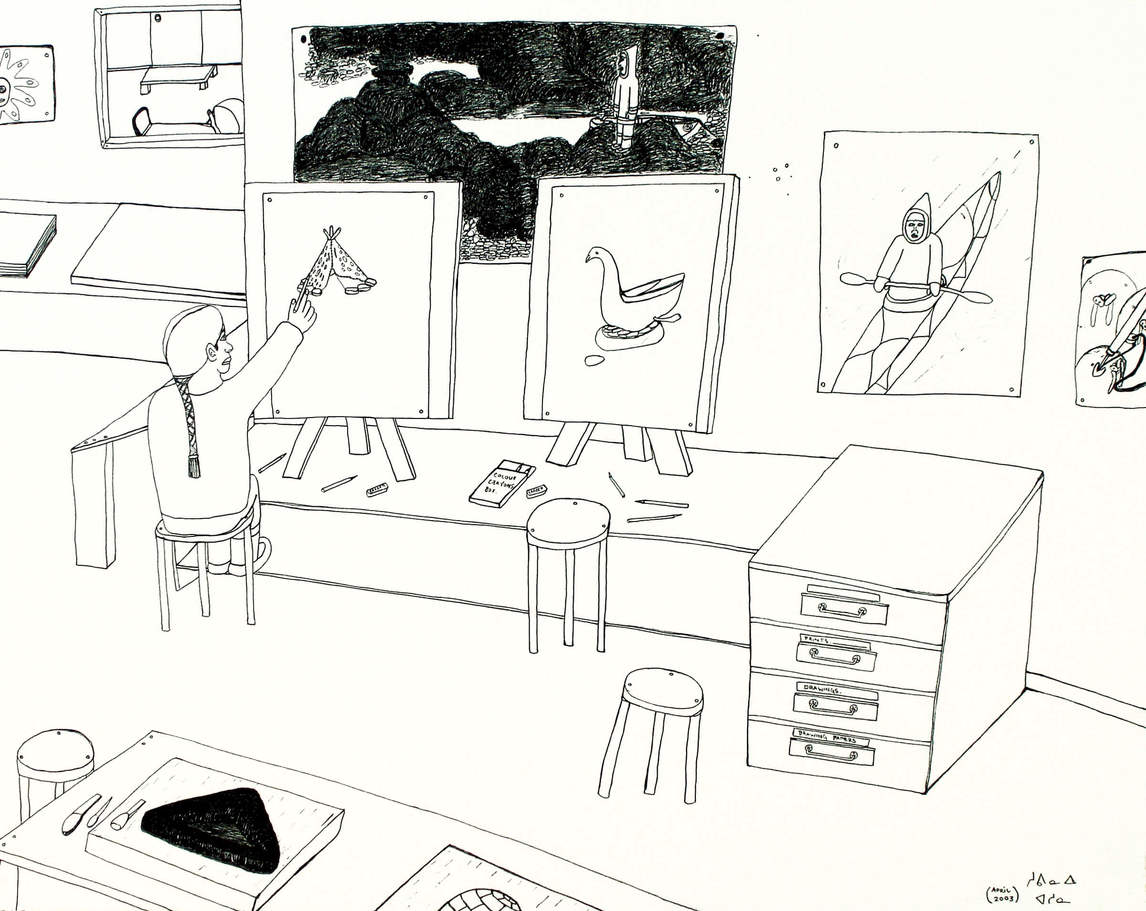

The varied styles and techniques of her early works demonstrate the artist’s willingness to experiment and learn. She developed a technical command of the drawing medium by using only black ink and the negative space of white paper. Shuvinai’s exceptionally confident drawing style allowed for her to begin using black Fineliner pen, often without lifting the pen off the paper until the composition was almost fully resolved. A more recent monochromatic work, All Kinds of Spiders in Different Views, 2011, with its complex composition and intricate, elaborate detail, shows the artist having achieved a level of mastery with this technique.

Introduction of Colour

In the early 2000s Shuvinai Ashoona introduced colour into her work, primarily through coloured pencil, which offered her more options for her drawings. She began to apply bright, concentrated colour in select areas, enhancing and punctuating her accomplished ink compositions. An early example of this is Composition (Community with Six Houses), 2004–5, in which she incorporates pink and blue houses within a highly rendered black and white tiered landscape. Once she started experimenting with this medium, Shuvinai quickly developed a sophisticated understanding of the palette and her drawings became filled with colour.

In Composition (QAMAQ), 2006, pencil crayon brings colour to the delicately detailed black Fineliner pen outline of the sealskin tent set against the rocky tundra. Soft greys, browns, and greens effectively recreate the subtle depth of hues in the fur. As Shuvinai became more confident in her use of colours, she boldly added purple or lime green, robin’s-egg blue, bright red, and more.

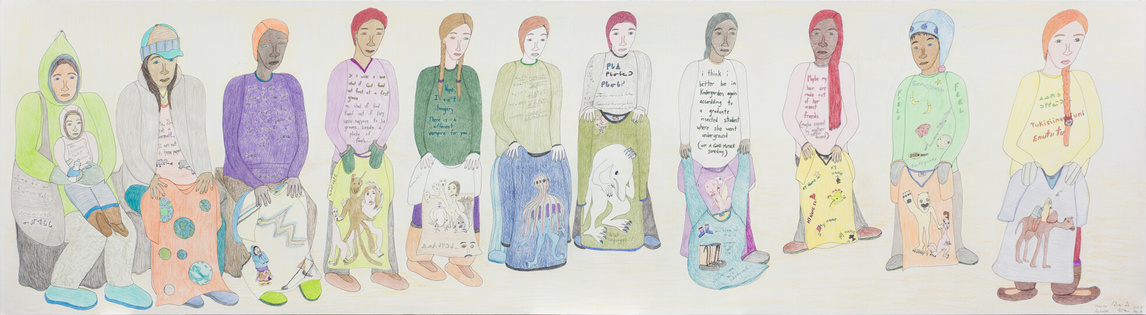

The representation of people in Shuvinai’s compositions from the early 2000s to today offers an interesting insight. The people who appear in her drawings share a broad palette. For example, in Audience, 2014, the crowd includes people of rich diversity, with a range of skin tones and hair and eye colour, reflecting the many nationalities the artist has been exposed to, both through her access to and love of television, which has broadcast the world to Shuvinai, and in Iqaluit and Kinngait, which are becoming increasingly multicultural communities. Her representations are a method by which Shuvinai directly reflects the racial realities of our modern world.

Textual Elements

Shuvinai Ashoona speaks and writes fluently both English and Inuktitut and she uses both English lettering and Inuktitut syllabics in some of her work. These are not meant to be labels or titles, as in the drawings of artists such as Napachie Pootoogook or Pudlo Pudlat (1916–1992), who often narrate what is happening in the picture; rather, words in Shuvinai’s artworks are part of the composition, with the textual elements adding a complexity to the image.

A fine example of Shuvinai’s inclusion of text is seen in Composition (Egg in Landscape), 2006, a drawing of two inscribed eggs in a nest of grass. The English wording says, “They shall have seven colours of hair and for the first time lie to the purple linen / I will always find out why.…” The syllabics on the other egg translate as: “Where are we going, who are we? Thoughts? Brain. Wondering if it’s going to open. How to spit?” In both languages, the text is lyrical and at the same time cryptic.

Shuvinai’s use of language in her drawings is poetic and has a prophetic quality. Though why she sometimes includes textual elements in her work remains unclear, when text appears it offers viewers a rare vantage point from which to observe both the artist’s artistic process and her state of mind.

Layering

Typically Inuit drawings are two-dimensional renderings of a scene or an activity. The artist places elements on a flat picture plane and makes little use of perspective or depth. Often the compositional elements on the paper are placed side by side or scattered. Shuvinai’s early ink drawings of her community were composed in a similar fashion, but she quickly developed a process of layering images within her pictures.

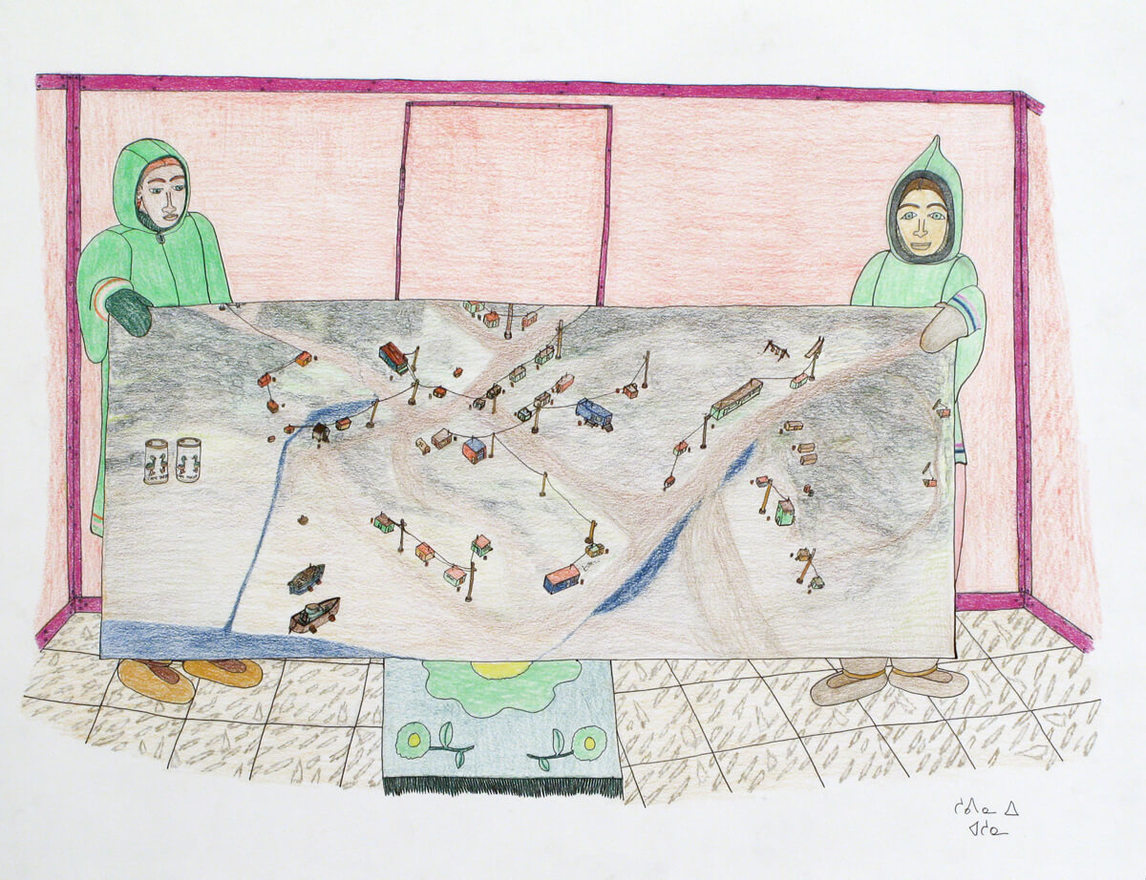

This technique is apparent in Three Cousins, 2005, in which Shuvinai represents herself, Annie Pootoogook (1969–2016), and Siassie Kenneally (b. 1969), each presenting one of her drawings to the viewer. The subject of artists holding up drawings for inspection has appeared multiple times in Shuvinai’s work—for example in Composition (Self-Portrait), 2005; Composition (Showing Drawings at the Co-op), 2008; and Artists Indoors Holding Outdoor Drawing, 2010—and in the work of artists who came before her, most notably in The Critic, c. 1963, by Shuvinai’s grandmother, Pitseolak Ashoona. It is understood as a representation of the artists proffering drawings for purchase or critique. In Three Cousins, a family portrait so to speak, Shuvinai makes the artists identifiable by their work. Siassie Kenneally holds a drawing of a fish head, one of the many drawings in which she isolated foods used for soups or stews, while Annie Pootoogook holds a drawing she made of a pair of scissors, and Shuvinai holds a version of a drawing she made of a woman holding yet another drawing of a woman. Here Shuvinai employs the layering technique to depict an everyday subject, but at the same time she ironically plays with the commercial element of art production in Cape Dorset.

Kinngait Studios manager William Ritchie (b. 1954) initiated a technique by suggesting studio artists use objects from everyday life in isolation to symbolize an activity. Annie Pootoogook did this often, notably in Kijjautiik (Scissors), 2007, and Coleman Stove with Robin Hood Flour and Tenderflake, 2003/4. Shuvinai experimented with this technique, though very briefly. For example, in School Bus, 2007, a large, orange, easily identified school bus, with the faces of its passengers clustered in the windows, dominates the image, suggesting the regular transport of children from around Cape Dorset to the local school.

Although this and other images show Shuvinai attempting the technique introduced by Ritchie, she ultimately prefers compositions that combine multiple objects, often with unusual colour combinations and in ways that diverge from representations made by other northern artists; however, underlying themes of family, community, and connection to the land are always present in her compositions. As curator Bruce Hunter writes: “Shuvinai has an intuitive sense of compositional elements, and they always rest securely in nature. Her world(s) are a floating and colour-infused metaphor for the centre of family life that is positioned on an axis in space and held in place through a galactic network of anchors and supports extending from within the larger community.”

Beyond the Frame

With the support and encouragement of Kinngait Studios, Shuvinai has stretched her practice by trying new formats. Composition (Overlooking Cape Dorset), 2003, in which she cleverly links multiple sheets of paper together to illustrate an aerial view of the community, was the first of such experiments for Shuvinai and the first attempt at a large-scale drawing produced in Cape Dorset. She achieved it by pinning multiple sheets of paper together to allow for an expansion of surface on which to create her vision. The use of large-format paper in Kinngait has been relatively recent, since about 2006. Shuvinai adapted quickly to the new format and has proven to be adept at large drawings, masterfully filling the picture plane in great detail, as can be seen in Untitled (Eden), 2008, and Untitled (Yellow Amauti), 2010. But such works prove challenging and time-consuming given that her primary drawing material is coloured pencil.

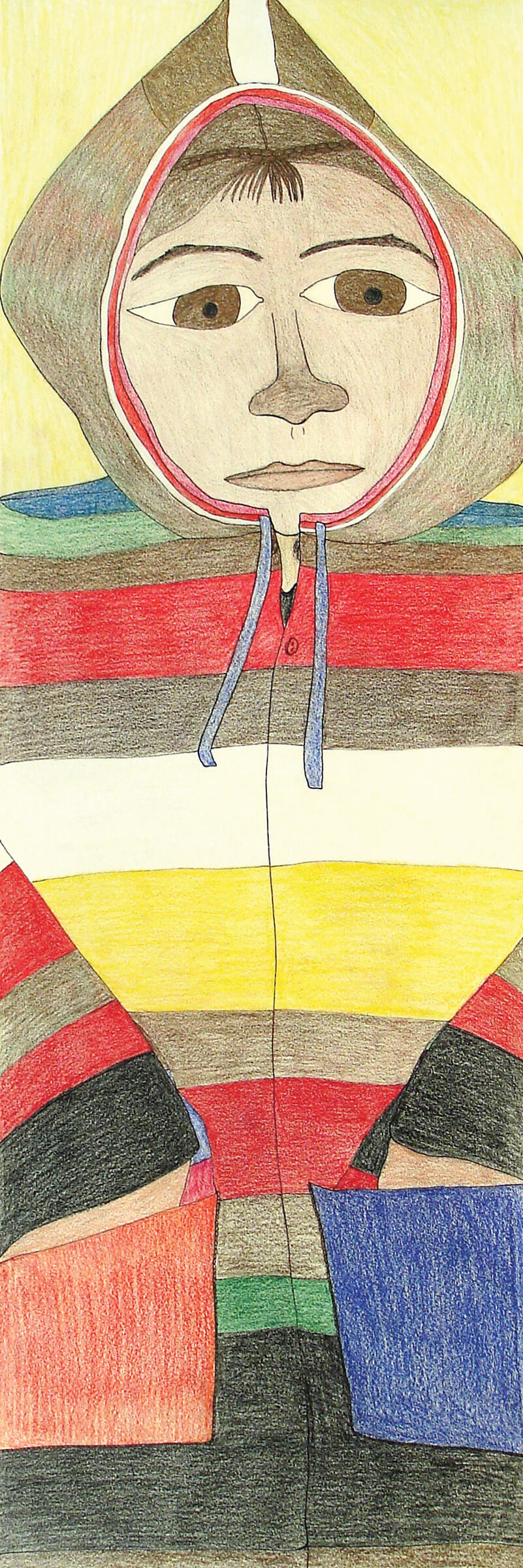

The studio has also encouraged Shuvinai to explore a long, rectangular format, which she has employed vertically in a series of portraits. For example, Composition (This Is My Coat of Many Colours), 2006, is a rare self-portrait of the artist in her favourite coat of colourful stripes, and Priest, 2006, is a long, vertical image of an unidentified clergyman. Other vertical images picture people she has met or seen on television, although, like the priest, they are seldom identified. These portraits occasionally make social commentary, as seen in Carrying Suicidal People, 2011, and Oh My Goodness, 2011, which respectively address the startling suicide rates in her community of Kinngait and the disturbing aftermath of Japan’s 2011 tsunami. Shuvinai occasionally turns the rectangular format sideways and presents images in a horizontal manner. A wonderful example of this is seen in In The Gallery, 2009, in which the artist depicts a scene from an art exhibition in the South that includes her work among the others on display.

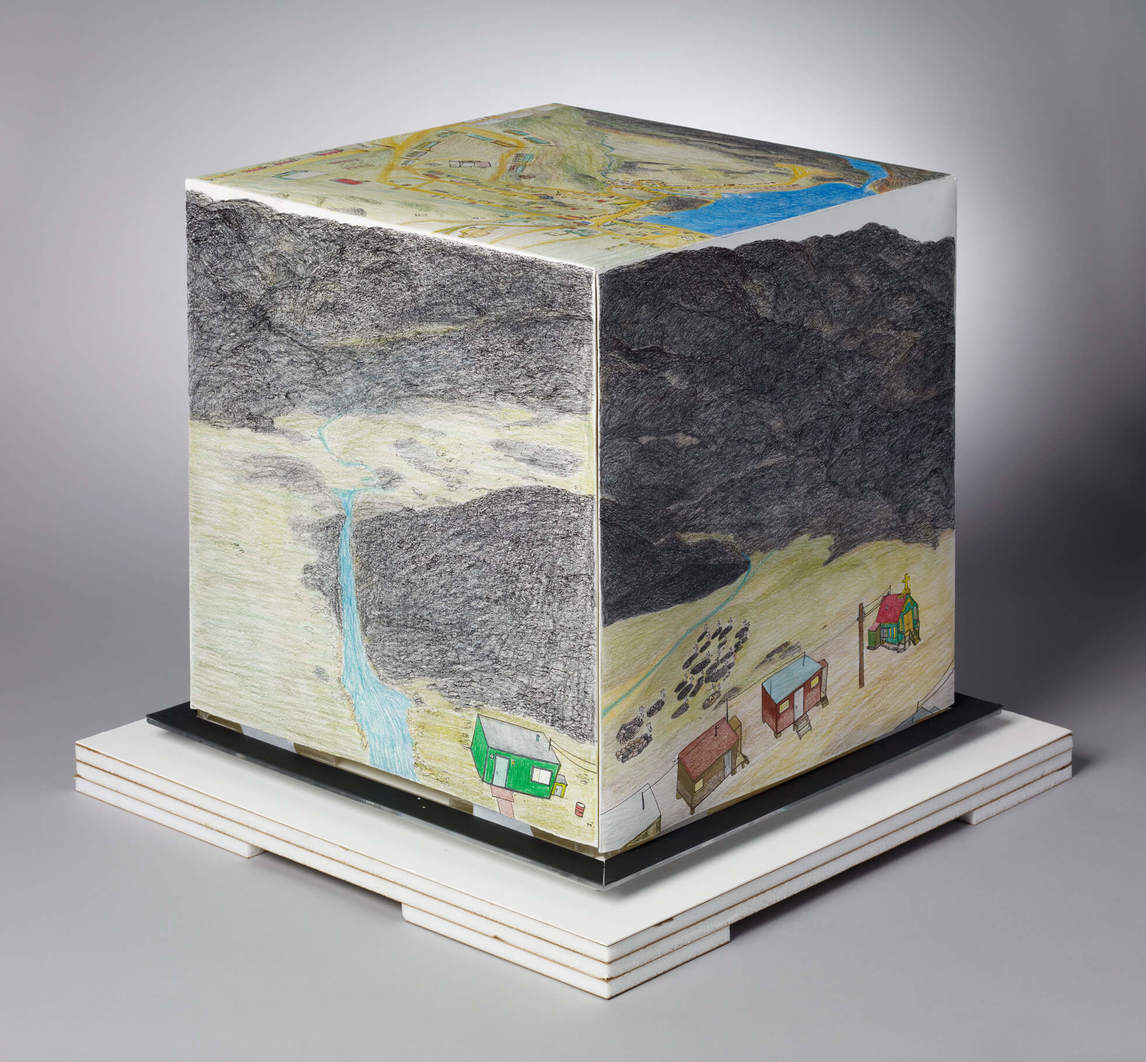

Shuvinai has also experimented with three-dimensional drawing and is urged to do so by the studio. She produced a unique pencil crayon and ink drawing Composition (Cube), 2009, that forms a cube when assembled and was purchased by the Art Gallery of Ontario. Shuvinai has recently worked on three-dimensional pyramidal drawings as well.

In 2008 Brad van der Zanden, musician and manager at Feheley Fine Arts, offered to make a guitar for the gallery’s long-time client and patron of Inuit art Kevin Hearn, of the band Barenaked Ladies. Hearn suggested that an artist draw on it; van der Zanden agreed and sent several guitar bodies to Kinngait Studios for artists to ornament. According to van der Zanden, “When I received the first group of six instruments back from the north we gave [Kevin] first choice and when it was completed we gifted it to him. The artists involved at that time were Qavavau [Kavavaow Mannomee], Shuvinai, Jutai [Toonoo] and Ningeokuluk [Teevee]. Shuvinai seems to have enjoyed the project most, along with Tim [Pitsiulak], and so we produced more in the subsequent years. In total I have handmade eighteen instruments featuring the artwork of various artists from Cape Dorset—six guitars, two bass guitars, and three ukuleles with artwork by Shuvinai.”

Hearn selected one of the guitars with artwork by Shuvinai. Although he had met Shuvinai at Feheley Fine Arts in 2012, it was during a visit to Cape Dorset in 2014 that he again connected with the artist. In the song he dedicated to her on his recent solo album, Walking in the Midnight Sun, he writes, “Shuvinai went walking by the frozen sea, looking at things that were invisible to me / Creatures by the floe edge and on the ancient trail … When she speaks to me, though I try to understand, it’s like trying to catch water in my hand.”

Printmaking

Since 1959 the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative has produced an annual print collection of between thirty and sixty images, which since 1978 have been marketed to commercial galleries and institutions through Dorset Fine Arts (DFA). Around the mid-2000s the arts and crafts sector of the co-op began to be referred to as Kinngait Studios. It is the oldest continuously running print studio in Canada and boasts some of the most talented printmaking technicians in the world. For many years art enthusiasts have been aggressively collecting studio prints, and many annual releases sell out.

Between 1997 and 2016, twenty-nine prints based on drawings by Shuvinai Ashoona were included in the Cape Dorset Annual Print Collection. Shuvinai works primarily in lithography. In stonecut printing, another common method used by artists in Cape Dorset, the printmakers redraw everything, but with lithography the artist’s hand is preserved. As Kinngait Studios manager William Ritchie (b. 1954) explains, “The artist always draws the key images on plates, stones, or mylars, which is the beauty of the medium.”

Relatively few prints by Shuvinai have been included in the annual collection of Cape Dorset prints, and the sale of her prints is not as robust as that of some of the other Kinngait artists. Perhaps this is because her drawings tend to be highly detailed rather than graphic or iconic, as the most successful prints are. Shuvinai often fills an entire sheet of paper with complex details that are hard to translate to stonecut or lithography. Her non-traditional subject matter is also not what collectors of Inuit prints necessarily want in their collections.

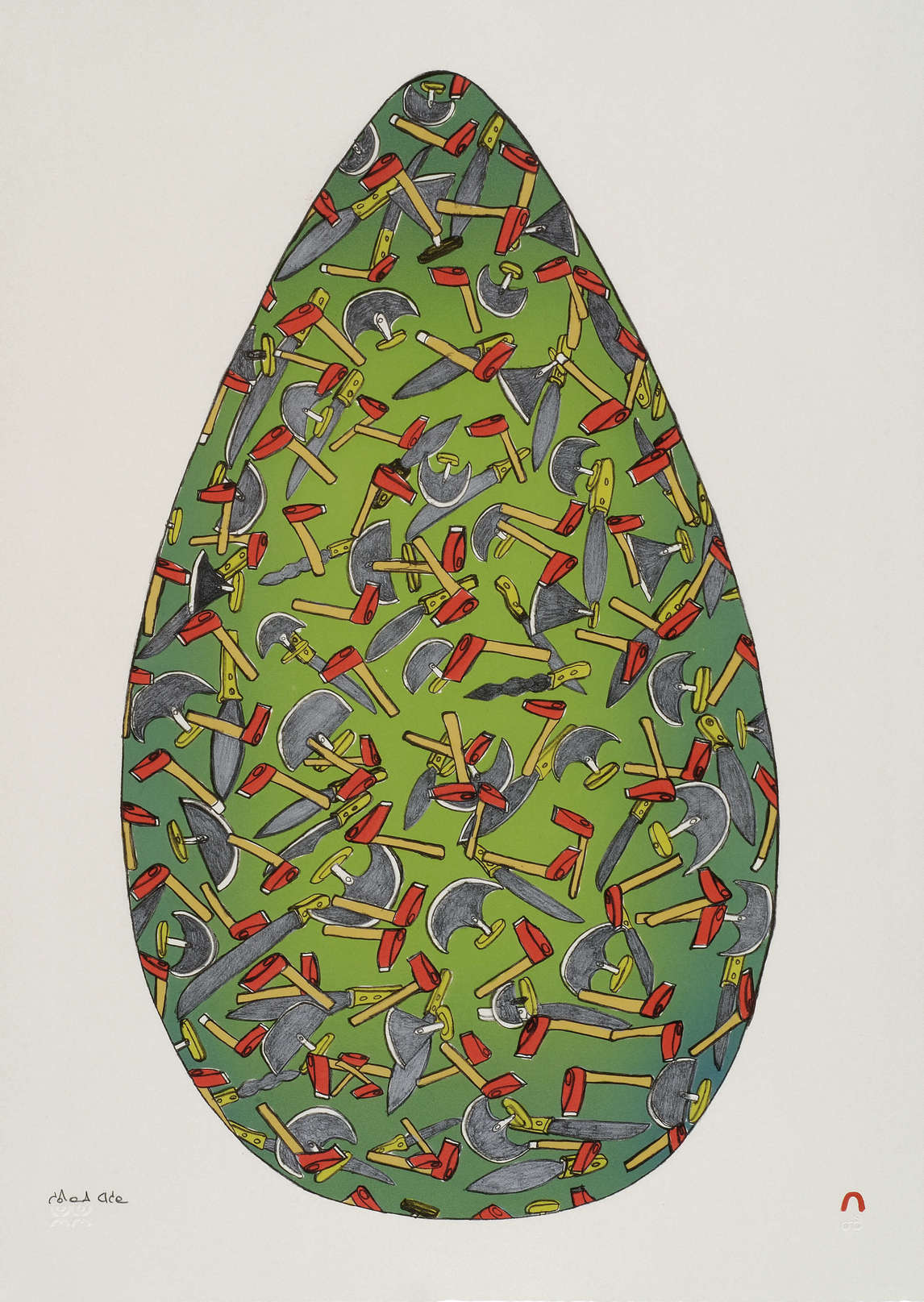

Ritchie explains, “I think there is a different market for her drawings, [these collectors] are more adventurous and not looking for stereotypes. It is funny, when people extol the virtue of the Dorset aesthetic they trot out Shuvinai as an example of the work we’re doing. I love her work. I love Scary Dream, 2006, which I really had to fight to get included in the collection by DFA. I also really love her green egg with the tools floating inside, a beautiful lithograph and a fine example of Shu and the skill of the printer.” Here Ritchie refers to Egg, 2006, one of the few prints by Shuvinai Ashoona included that year in the annual release of prints. A single dark-green egg is placed tip up in the centre of the page, the egg marked with repetitive tools, uluit (the ulu is a woman’s knife), other knives, and axes that connect to create a pattern of industry on the surface of the egg. The tools are perhaps simply placed there to help the egg crack open and bring new life into the world.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements