When Shuvinai Ashoona started making drawings at the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative in the mid-1990s, many of the older artists were baffled by her interpretation of the world. As a third-generation Inuit artist from a famous family of artists, Shuvinai was encouraged and deeply influenced by her predecessors, yet her distinct sensibility and bold experimentation has brought new regard for Inuit art. Beginning in 2012 at the Sydney Biennale, her drawings have been exhibited internationally with the work of other contemporary Canadian artists.

Working in a Co-operative Model

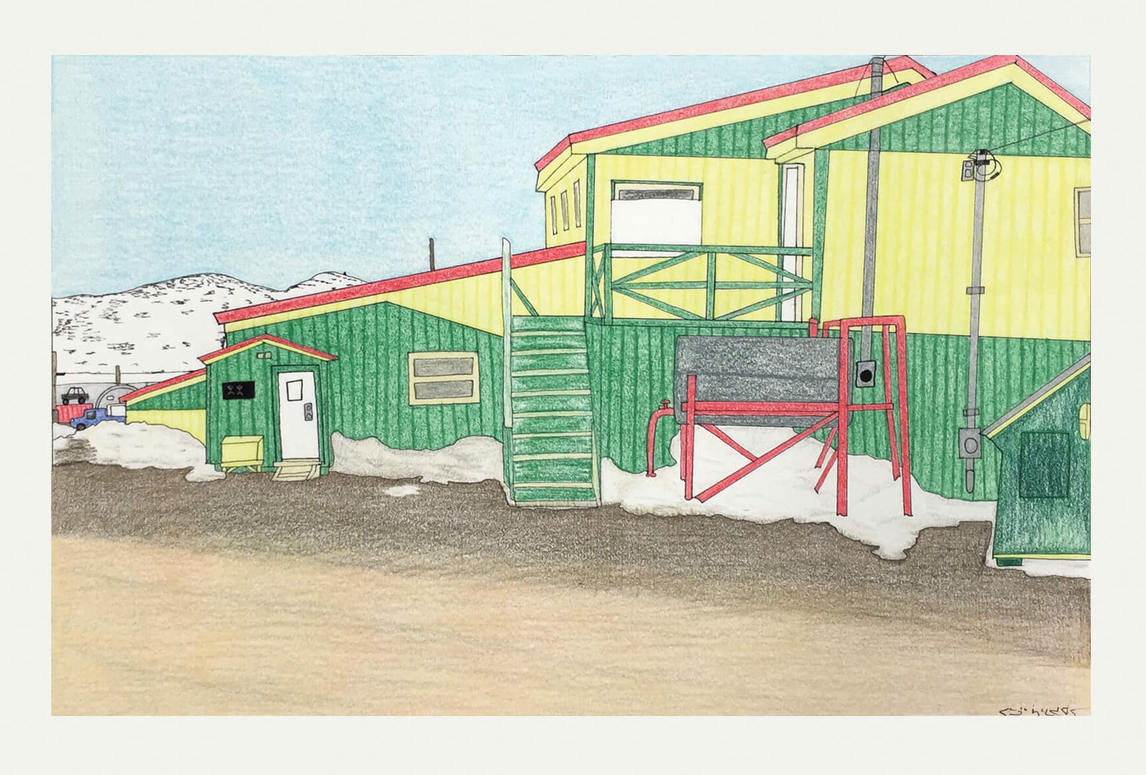

Shuvinai Ashoona’s hometown, Cape Dorset (now referred to as Kinngait), is best known for its production of prints, graphics, carvings, and other types of Inuit art. Her community is said to have more artists per capita than any other in Canada, and the art studios there have the strongest and longest tradition of co-operative artmaking in the Arctic. The co-op was first incorporated in 1959 as the West Baffin Sports Fishing Co-operative and reincorporated under the name West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative in 1961; since around 2006 the arts and crafts sector of the co-op has been known as Kinngait Studios. Due to the stability and longevity in the co-op’s management, four generations of Inuit artists have been able to develop and sell their art around the world.

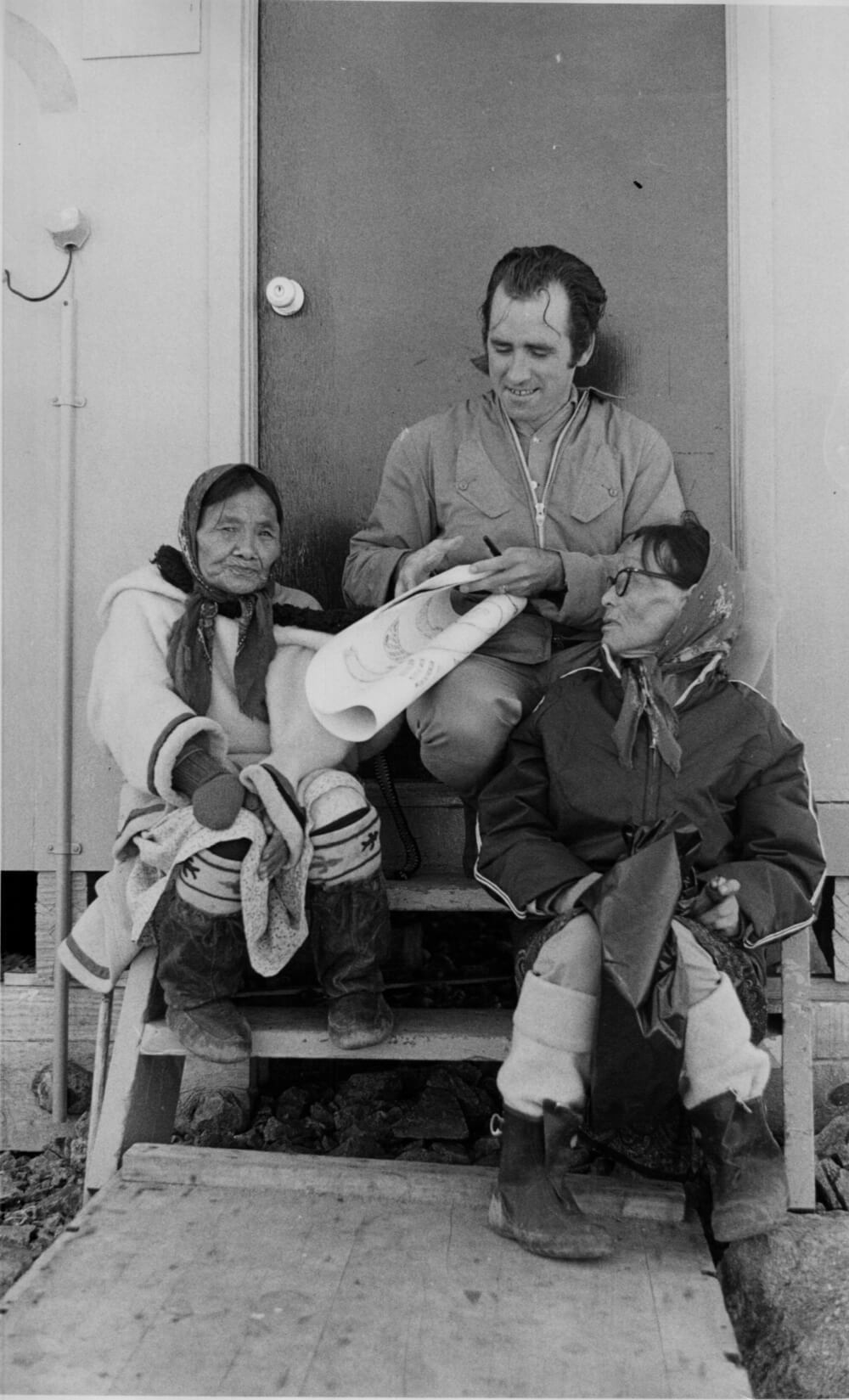

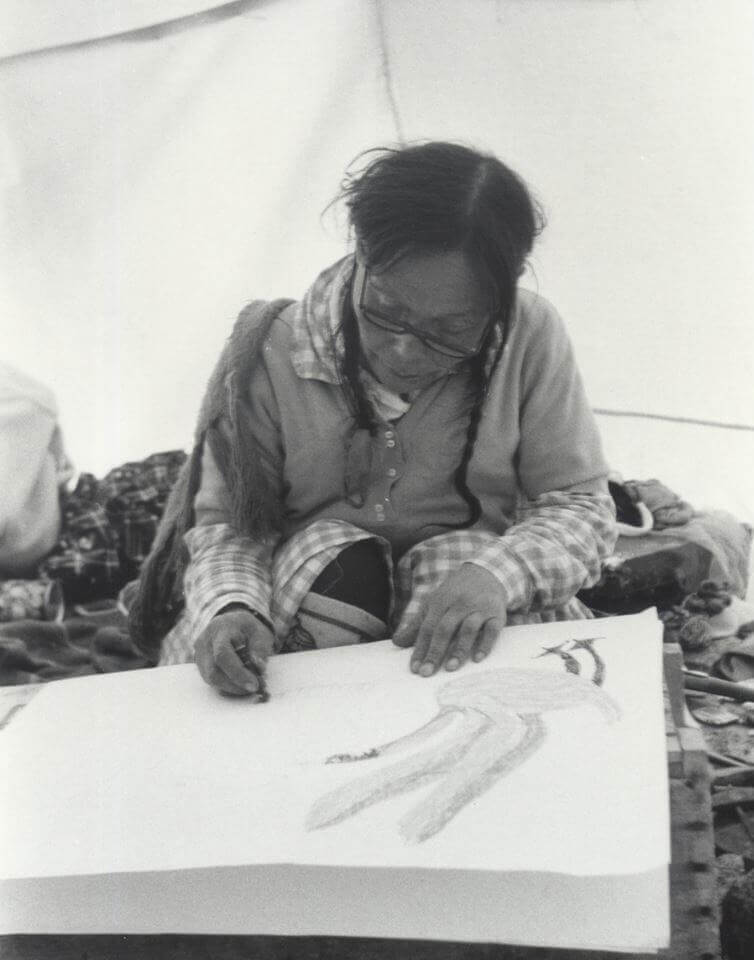

The early years of the co-op were productive for artists in Cape Dorset who were curious about and interested in participating in a fledgling print program at the studio. With the co-op’s support and the opportunity to experiment, Cape Dorset artists seemed to explode onto the Canadian art scene, making their art and their vision part of the Canadian consciousness. Shuvinai Ashoona’s grandmother Pitseolak Ashoona (c. 1904–1983) was among the first generation of Inuit artists producing drawings and prints at the studio in the mid-twentieth century.

Dorset Fine Arts, an initiative to aid in the marketing and distribution of art from Cape Dorset, was established in Toronto in 1978. In 1983 the co-op’s then long-time general manager Terrence Ryan (b. 1933–2017) moved from Cape Dorset to Toronto to run Dorset Fine Arts. Ryan and his wife managed the production of the prestigious and sought-after Cape Dorset Annual Print Collection and catalogue. They also developed a network of dealers across North America and established Dorset Fine Arts in Toronto as an intermediary between the co-op and the dealers, and they helped organize community visits for artists from the South travelling in the North and fine arts programs for the benefit of Cape Dorset printmakers, carvers, and other artists.

By the time Shuvinai Ashoona began visiting the co-op in the late 1980s, it had long been famous for its annual print collection. Historically drawings have been viewed almost exclusively as source images for prints, but the studio is now a major centre for drawing as well. This shift can be attributed to an increased desire for original drawings in the changing market for Inuit art. Through the advocacy of Dorset Fine Arts; of art adviser and current manager of Kinngait Studios, William Ritchie (b. 1954), who plays an influential role for the co-op artists; and of progressive dealers of contemporary art in the South, such as Feheley Fine Arts and Robert Kardosh Projects, collectors and curators have become aware of the depth and breadth of drawings produced in the North as they enthusiastically purchase, promote, and exhibit this work. At the co-op, Shuvinai’s artistic output is remarkably high. In 2015–16 she produced more than fifty works, including drawings and lithographic plates.

With co-op membership, artists gain access to supplies and the studios, though an increasing number of drawing artists and sculptors elect to work offsite. The economic model is such that, without exception, the co-op pays artists at source for production. The co-op purchases work from its members and the artists are paid according to the scale of the work and the stage of the artist’s career. Dorset Fine Arts then sells the work to its distribution galleries, which in turn retail the drawings, prints, and carvings to institutions and private collectors. Historically this has served artists well, as the studio provides materials and workspace as well as the opportunity to network their work in the South. Kinngait Studios remains relevant today and helps northern artists negotiate the art market in the South.

Third Generation

At Kinngait Studios artists are often referred to by their generation. The first generation includes those who spent their formative lives on the land and were members of the core group of artists involved in the co-op; for example, Shuvinai’s grandmother Pitseolak Ashoona is perhaps the best-known and one of the most prolific first-generation Inuit artists. Pitseolak is the grandmother to many artists and has left a significant artistic legacy, contributing hundreds of drawings and prints to the co-op and its print shop.

But Shuvinai has a radically different life from that of her famous grandmother. Pitseolak grew up entirely on the land, before there was a strong influence from the South in her culture, and she travelled to the South only later in her life. Shuvinai has had access to popular culture; when she and her family weren’t living on the land, their homes would have had televisions, and Shuvinai watched movies, either at community screenings or on VHS at home. As an adult, she has had very limited access to computer technology and social media. She lives in an era during which global warming has had a noticeable effect on the climate, landscapes, and lifestyles of the North; works such as her Earths with People on Them, 2010, can be read as a commentary on the environment—both social and geographical—of the North. Shuvinai has travelled to the South and has collaborated with contemporary Canadian artists.

The second generation comprises those artists who were born on the land but lived in Cape Dorset most of their lives; these are often relatives of artists of the first generation; for example, Shuvinai’s father, Kiugak Ashoona (1933–2014), and her aunts Napachie Pootoogook (1938–2002) and Mayoreak Ashoona (b. 1946). The third generation includes artists such as Shuvinai, who have lived their entire lives in and around the community of Kinngait. There is a small, emerging fourth generation of artists who have spent their whole lives living in town, connected throughout the North and the world via limited access to the Internet. Among the promising talents is Saimaiyu Akesuk (b. 1986). Some families, such as the Pootoogooks, Ashoonas, and Ashevaks, are represented in every generation of artists in Kinngait.

Shuvinai Ashoona has altered expectations for Inuit art, her drawings evolving the form from what was once considered a market-driven product to an avant-garde art practice. With some of the other third-generation artists, including her cousin Annie Pootoogook (1969–2016), Kavavaow Mannomee (b. 1958), Tim Pitsiulak (1967–2016), and Ningeokuluk Teevee (b. 1963), Shuvinai has begun a practice of self-representation by producing art that responds to the complicated impact of a century of colonial influence in the Arctic. For example, in Titanic, Nascopie, and Noah’s Ark, 2008, Shuvinai references the Titanic, a ship whose disaster was made current for her in James Cameron’s 1997 film of the same name; the Nascopie, a notorious supply ship that, until it sank in 1947, delivered goods to the remote hamlet of Cape Dorset; and Noah’s Ark from the Bible. These three ships are conflated in a single boat that chases a giant squid and Inuit fishermen. The past, present, and uncertain future of her home are included in this image’s fantastical narrative.

Contemporary work coming out of the North has been described as “sites of resistance” by Australian archaeologist Claire Smith. Art historian Heather Igloliorte prefers “expressions of resilience.” Resilience is a trait of Canadian Inuit in general, and to see Inuit artwork as an expression of this resilience is to see art as fortifying the culture from within, rather than as a reaction to outside forces.

Yet carving, printmaking, and drawing (the aesthetic categories of the North) can also be viewed as the fluid product of a hybrid of influences. The legacy of the Inuit’s unique cultural insights into the workings of nature, humans, and animals (known as Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit) affects the production of work. However, Shuvinai Ashoona, like many artists of the North, is adapting to the rigorous aesthetic scrutiny of the mainstream art world by producing drawings that are ambitious, personal, tough, and informed. Works such as Earth and Sky, 2008, or Oh My Goodness, 2011, both in the collection of the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, engage the viewer in a conversation that posits Inuit art as further-reaching than idealized representations of the Canadian North and as an art form with global import.

Personal Iconography

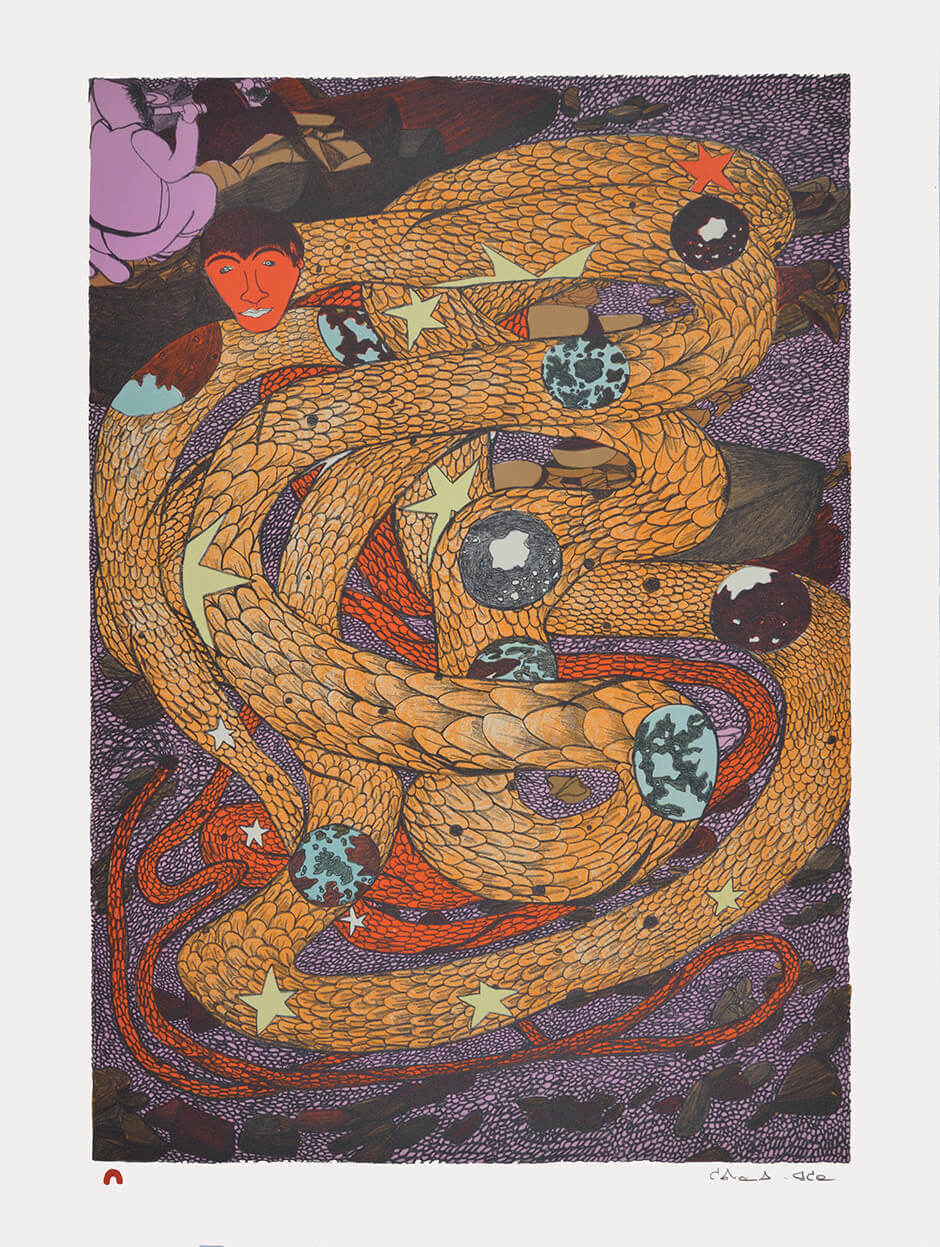

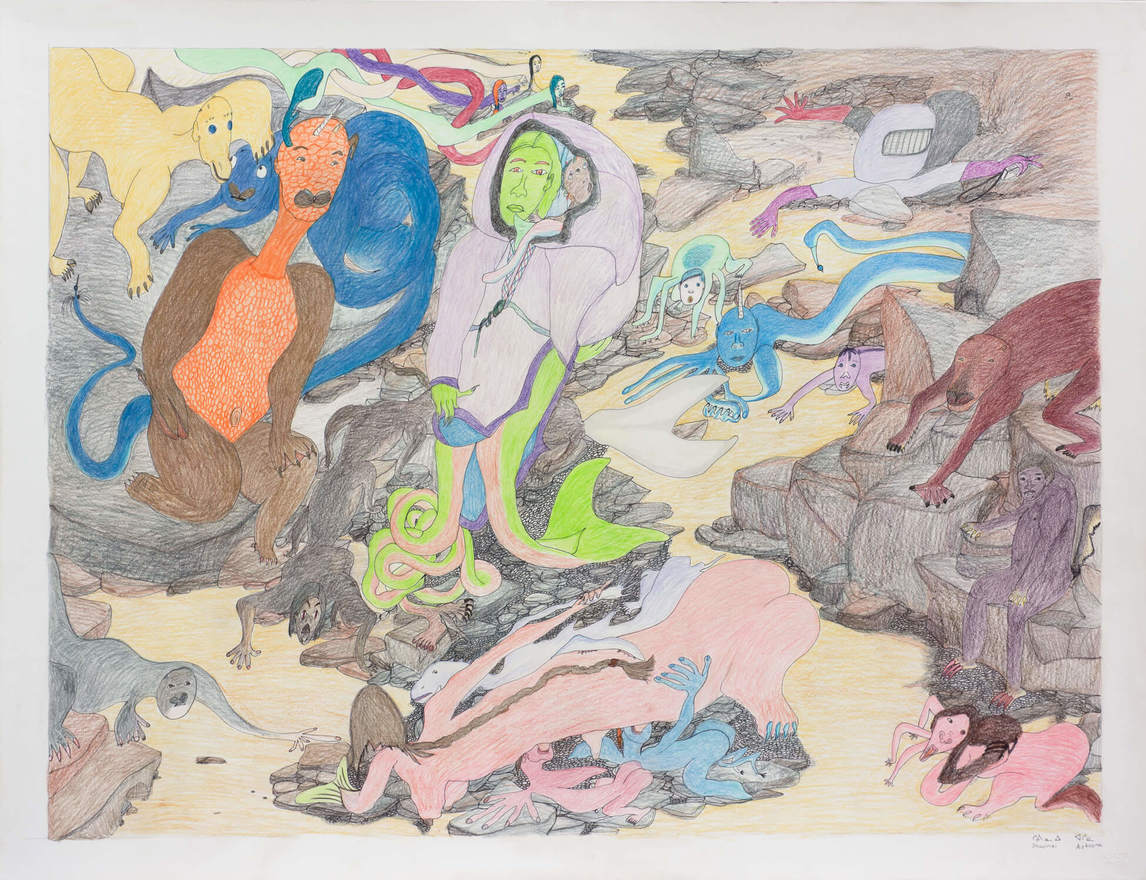

In many of her drawings Shuvinai Ashoona references traditional Inuit iconography, from daily life to shamans and mythic figures such as the sea goddess Sedna, but she is best known for developing a highly personal iconography. With imagery ranging from closely observed naturalistic scenes of her Arctic home to strange, monstrous, and fantastical visions, she evokes altered states of mind and shifting perceptions. As can be seen in the 2014 print Inner Worlds, her bold and often inexplicable images can be disturbing, depicting hybrid creatures and dark, fanciful landscapes. Shuvinai has not been directly influenced by the Surrealists, though her art can be likened to how the movement drew influence from an inner vision. Shuvinai’s sources are her vivid imagination and her environment, infused with her fascination with horror films, comic books, and television.

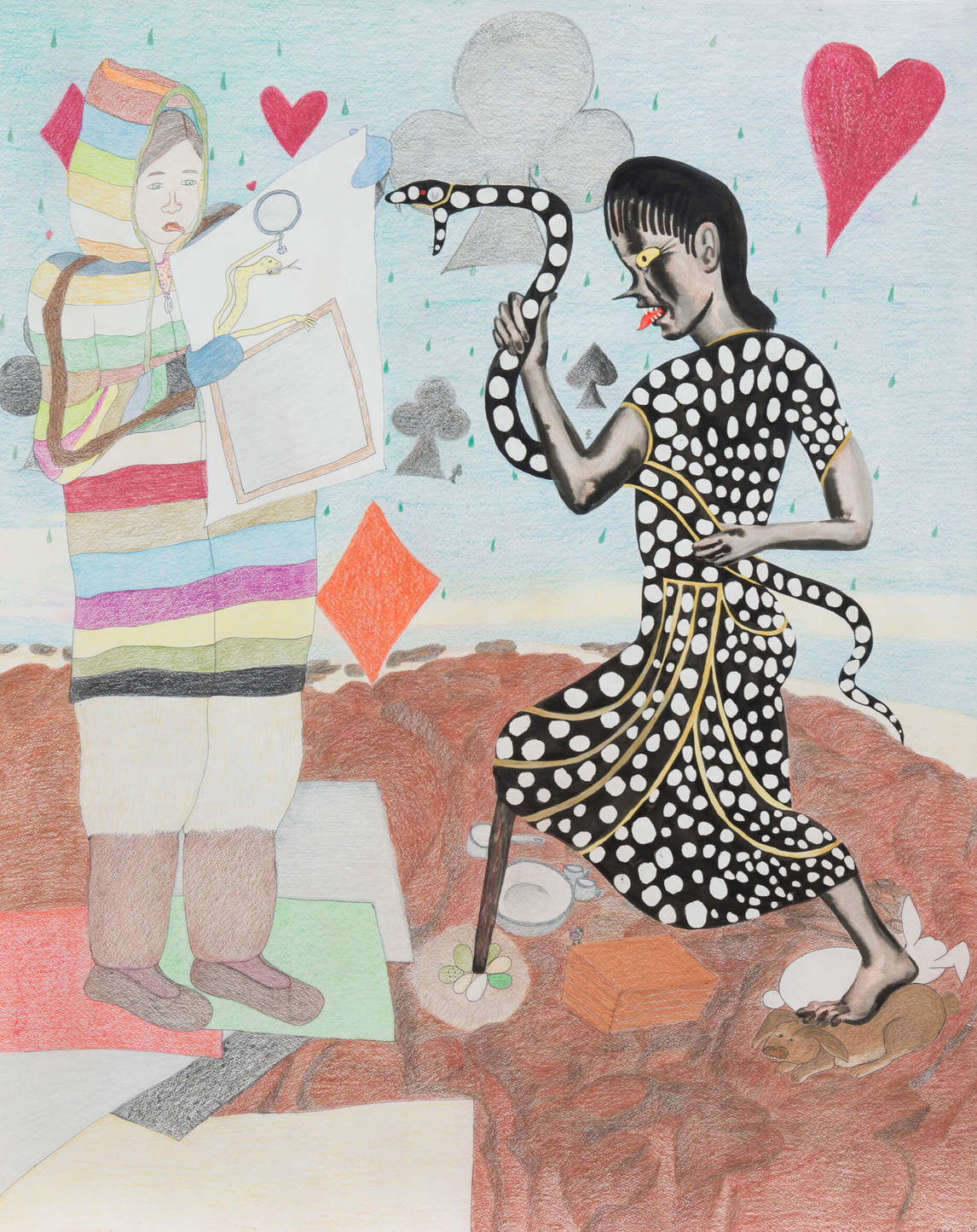

Images drawn from playing cards—the spade, club, diamond, and heart—are present in her work, as can be seen in Composition (Playing Cards), 2007–8, and Composition (Hands Drawing), 2014. Shuvinai carries a deck of cards with her, but rather than playing cards she lays them out in various patterns and seems to enjoy this process as much as the resulting artwork.

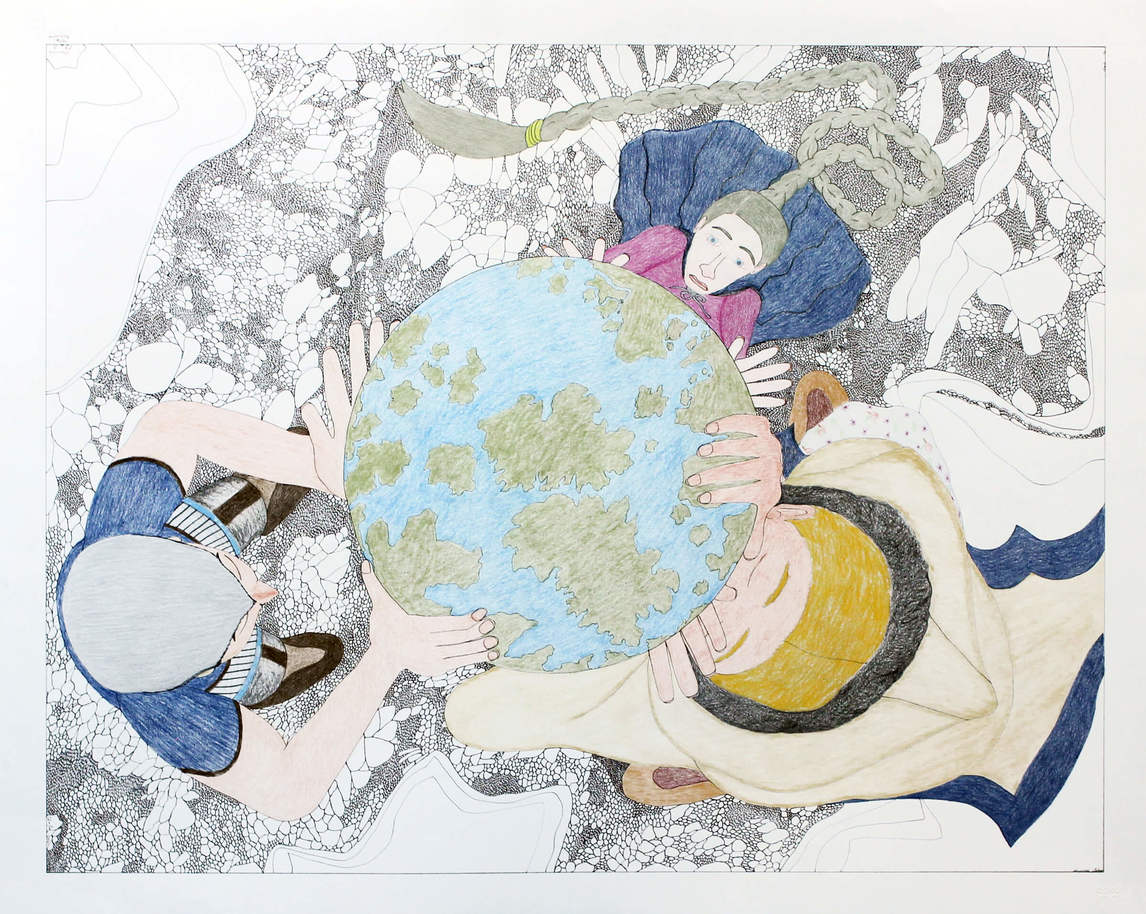

Another element is her frequent use of the globe. For a 2012 exhibition at Feheley Fine Arts, entitled Shuvinai’s World(s), she developed an entire series of works that feature the image of the globe: floating globes, people holding globes, even a woman giving birth to globes in Happy Mother, 2013. The globe drawings are usually optimistic: people of all races hold globes, or globes with arms and hands grasp animal and human hands in a circle of life. In Shovelling Worlds, 2013, multiple globes are integrated into a landscape of rocks that a standing human figure shovels, evoking the idea of connection between the terrestrial and extraterrestrial universes and the human connection to both.

In recent years sea creatures have figured prominently in Shuvinai’s work. They are often threatening, such as the large squid in Titanic, Nascopie, and Noah’s Ark, 2008, and the octopi in Composition (Attack of the Tentacle Monsters), 2015. Shuvinai’s initial interest in sea creatures likely developed when she was a young girl clamming on the beach, fishing, and seeing large sea creatures such as whales, walruses, and narwhals on the beach for butchering. Her attraction to these images was further fuelled after watching movies such as Jaws (one of her favourites) on television. In 2015 when Shuvinai was in Toronto, she visited the Ripley’s Aquarium of Canada and was delighted by what she saw.

With the development and repetitive use of a personal iconography, which for Shuvinai includes eggs, playing cards, globes, and fantastical creatures or disjointed figures, she shifted away from common representations seen in Inuit art, away from images of animals or figures placed in sequence on the paper, toward a broader iconography. Her use of distinctive motifs reveals the artist’s unique thinking and perceptions but also shows the signs and symbols of everyday life in the contemporary North, as steeped in its Indigenous culture as it is influenced by the South.

North and South

The positioning of Inuit art within the mainstream of contemporary art in Canada and beyond is relatively recent. Not only has Inuit art seldom been seen as part of the contemporary canon in Canadian and international museums, but it has also been separated from other Indigenous art in Canadian museums. Shuvinai Ashoona, like her cousin Annie Pootoogook, has repositioned Inuit art. Shuvinai has broken with forms of representation adopted by previous generations of Inuit artists, created works in collaboration with artists from the South, and established an international reach with work that challenges stereotypes about life and artmaking in the North.

Shuvinai’s two major collaborations with contemporary Canadian artists have had significant impact on the visibility of her work and signal a new acceptance of Inuit art within global contemporary art exhibitions. Her collaboration with John Noestheden (b. 1945) in 2008 was initiated by Wayne Baerwaldt, a curator with great international reach. The collaboration resulted in the exhibition of a forty-metre banner for the Stadthimmel (“Citysky”) project, a public art installation at the Basel Art Fair in downtown Basel, Switzerland, curated by Klaus Littmann, with assistance from Edek Bartz. The Earth and Sky, 2008, banner was subsequently exhibited in Australia, where it was included in the 2012 Sydney Biennale All Our Relations, curated by Gerald McMaster and Catherine de Zegher, who were former curators at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto. The National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa also presented Earth and Sky in Sakahàn: International Indigenous Art in 2013. Shuvinai’s ongoing collaborations and exhibitions with Toronto artist Shary Boyle (b. 1972), an artist of international status who was the Canadian representative at the Venice Biennale in 2013, have also increased her profile and presented her work in contemporary contexts previously not considered for Inuit artists.

Inuit art has remained slow to hit the radar of international curators. Gradually through the work of artists like Shuvinai, whose drawings and prints challenge outdated expectations of what Inuit art should look like, Inuit artists are gaining international profiles outside the traditional Inuit market system. Shuvinai’s work was included in the American exhibition of Canadian art Oh, Canada: Contemporary Art from North North America at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA), North Adams, Massachusetts, curated by Denise Markonish in 2013, and in Unsettled Landscapes: SITElines: New Perspectives on Art of the Americas at SITE Santa Fe, curated by Canadian Candice Hopkins between July 2014 and January 2015. These recent inclusions speak to the increased accessibility of Inuit art material online and to the gradual inclusion of Inuit art in exhibitions of contemporary art.

Shuvinai is also featured in the 2013 Phaidon publication Vitamin D2: New Perspectives in Drawing, which highlights a new generation of artists who engage with drawing in innovative ways and introduces these artists to the world. Inuit art is constantly changing and adapting, like the culture itself, and Shuvinai Ashoona is pivotal in this change.

Shuvinai Ashoona’s drawings do not typically carry an overt message but rather present vignettes of life, either real or imagined. Having grown up watching television, Shuvinai is aware of both community and world issues. On the community level, she has addressed subjects such as suicide, which is rampant in Kinngait, as it is everywhere in the North. Carrying Suicidal People, 2011, is a drawing of two mythic people gently carrying lifeless, much smaller figures in their arms, the image made on a large, vertical sheet of paper that lends a sense of gravity and import to the work’s subject. Shuvinai has created numerous drawings of herself and people she has met or seen in her community or in Iqaluit. She was also deeply affected by television coverage of the 2011 tsunami in Japan, responding with the drawing Oh My Goodness, 2011.

Although aware of global issues such as climate change and threats to wildlife in the North, Shuvinai doesn’t tackle these subjects directly. Her eloquent description of the scene in Composition (People, Animals, and the World Holding Hands), 2007–8, is telling of her process: “I was thinking that they were having a meeting, a world meeting about the seals, polar bears … rethinking what the world would be for the animals. I started thinking that all of these animals would be friends, even some of the dangerous animals I have seen in the movies are there.”

Other works share this optimism for the future, such as Composition (Holding Up the Globe), 2014, which presents a group united in its effort. Shuvinai often mixes up skin, hair, and eye colour in the people who inhabit her drawings. Although Shuvinai never expresses her worldview in words, her drawings consistently reveal empathy for people, creatures, and the land while delighting in the unexpected and the imaginary.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements