Celebrated for her large-scale drawings, enigmatic subject matter, and collaborative work with contemporary artists, Shuvinai Ashoona (b. 1961) is a third-generation Inuit artist living in Kinngait, Nunavut. The dramatic changes in the North—the shift from life on the land to settled communities and access to popular culture—are reflected in her art, which overturns stereotypical notions of Inuit art. Her constantly evolving work is included in national and international biennales and exhibitions.

Early Years

Shuvinai Ashoona was born in 1961 at the nursing station in Cape Dorset (more recently referred to by its original name, Kinngait). Her father, Kiugak Ashoona (1933–2014), a hunter and master carver who gained international recognition in his own lifetime, was a second-generation Inuit artist, the youngest son of the great first-generation Inuit artist Pitseolak Ashoona (c. 1904–1983). Shuvinai’s mother, Sorosilutu Ashoona (b. 1941), was Kiugak’s second wife and an artist in her own right. Although Shuvinai was their first child, she was not adopted by her grandparents, as is Inuit custom, but stayed with her parents. She is the eldest of fourteen children, including three who died at birth. Her sisters Inuquq, Odluriaq, Mary, and Goota Ashoona (b. 1967) followed Shuvinai. The family adopted six other children: Shuvinai’s brothers, Salomonie, Inutsiak, Cee (b. 1967), and Napachie Ashoona (b. 1974), and her sisters Haiga and Leevee. As the eldest, Shuvinai helped to care for her younger siblings.

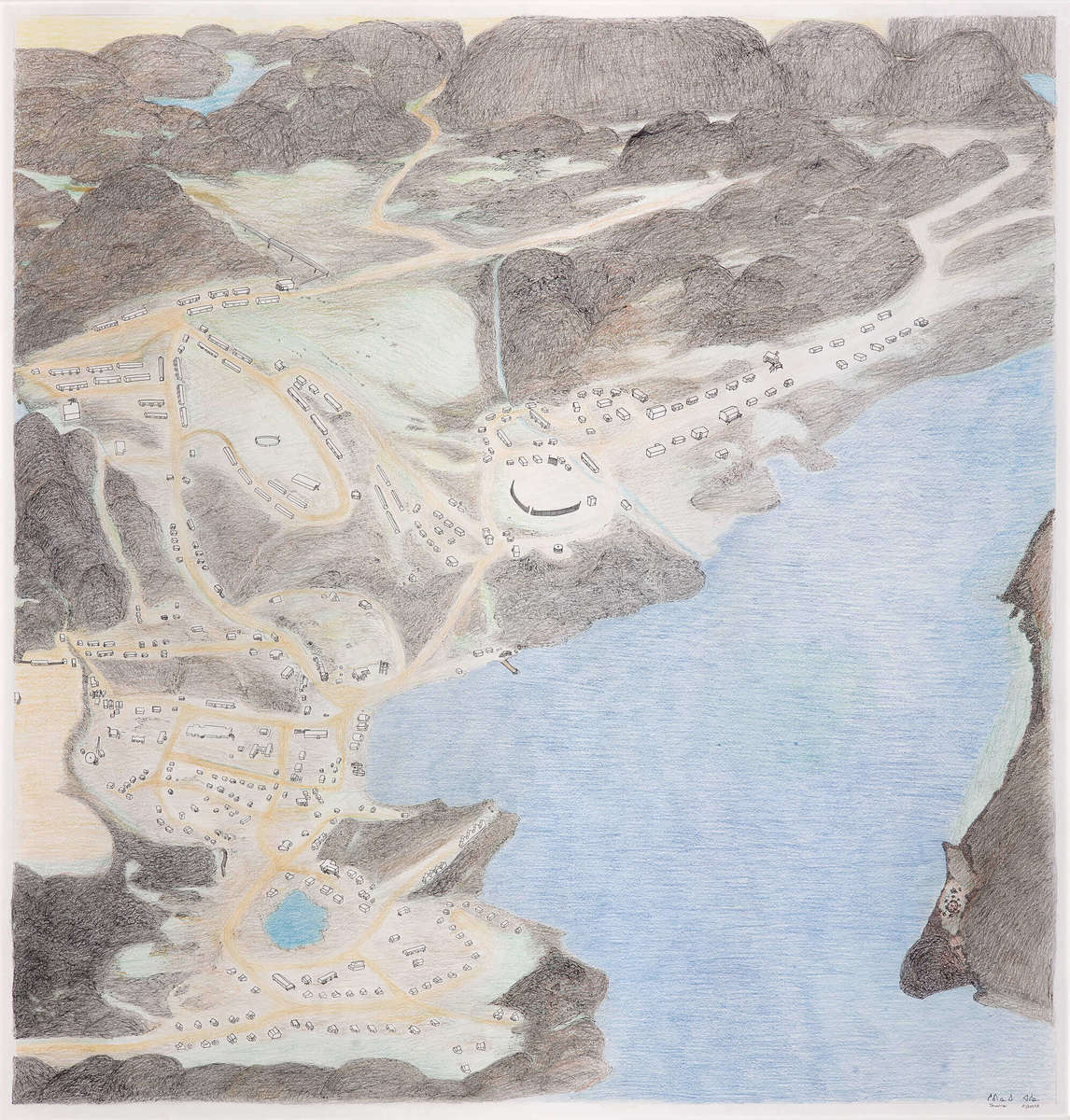

The family lived in the community of Cape Dorset, where by her account Shuvinai attended primary school for about five years. Shuvinai does not recall the desire to make art at a young age, but she enjoyed classroom activities and stories. She fondly remembers time spent out on the land in the summer months, particularly clamming with her family, boating, and camping. Later in life, she would depict many scenes of life on the land and in the town of Cape Dorset, as in Untitled, 2013, and Outside School, 2015.

Cape Dorset had been settled only relatively recently by the time Shuvinai was ready for elementary school, and she was part of the first generation of children to attend school in the town. With the encouragement of two of her teachers, Mr. and Mrs. Hohne, and the support of her parents, Shuvinai was one of very few students her age in Cape Dorset who planned to attend high school in Iqaluit, the largest city in Nunavut and a two-hour flight from Cape Dorset. The move was significant for Shuvinai, who had never lived apart from her family. She recalls being given a room in the dormitory but has no memory of actually staying there. She was frightened to be so far away from home, and she returned to Cape Dorset soon after she moved away. In 1977 Shuvinai became pregnant with her friend Joe Ottokie’s child and, when she was sixteen, gave birth to their daughter, Mary. Though Mary was given to Shuvinai’s parents for adoption, Shuvinai also stayed with her family and took care of her daughter.

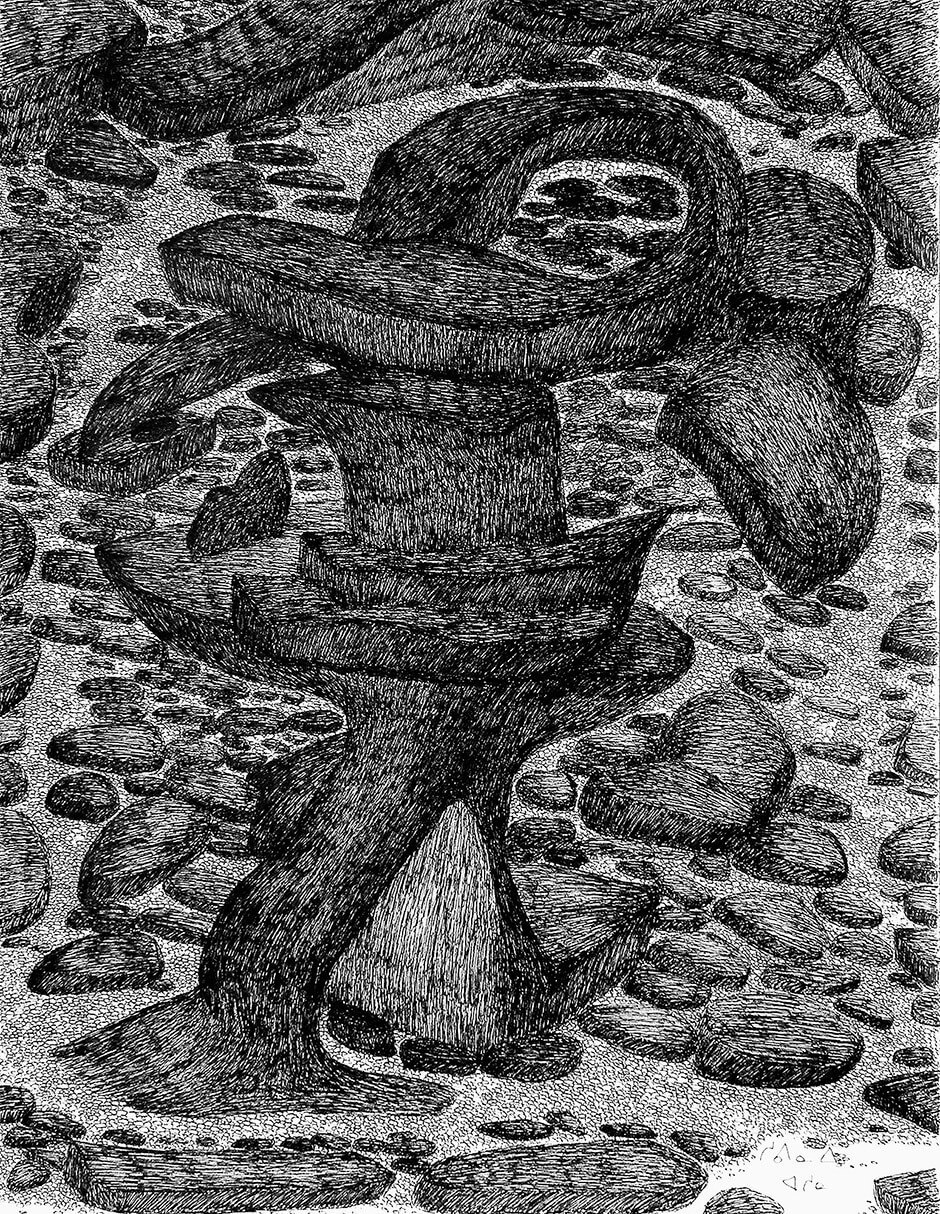

The Ashoona clan, including Shuvinai and young Mary, was unusual because they left Cape Dorset around 1979 and, for almost a decade, lived independently in outpost camps at Luna Bay and Kangiqsujuaq, returning to Cape Dorset only for holidays or the arrival of the sealift, a crane-bearing cargo ship that makes an annual delivery of supplies to remote Arctic communities. In the late 1970s and early 1980s very few families still lived a nomadic life on the land, largely relying on hunting and fishing for survival. The period in her late teens spent living the traditional Inuit way of life had a significant impact on Shuvinai’s art: it gave her an innate familiarity with the land and respect for it. In the drawing Tent Surrounded by Rocks, 2006, Shuvinai depicts from memory what life would have looked like when her large family-community camped and hunted on the land. No matter how fantastical her subject matter would become in later years, her work would always be deeply rooted in the experience of the northern landscape.

Return to Town

Toward the end of the 1980s, when she was in her late twenties, Shuvinai and her family moved back to Cape Dorset and settled in the town. Initially she shared a house with two of her sisters. Her daughter, Mary, lived with another sister, Odluriaq. The transition from living on the land to community life was difficult for the family, particularly for Shuvinai.

Mary recollected that her mother suffered greatly at that time. She recalled an episode at her home during which she was called to her mother’s side only to find Shuvinai with her neck and back muscles so tight with tension that her head was thrown back and her mouth stretched open. Mary’s descriptions of her mother’s symptoms sound like a seizure, but Shuvinai was convinced she was possessed by demons. Mary believes that her mother’s condition is likely genetic, as one of Shuvinai’s aunts suffered in much the same way, as does a sister and a nephew of Shuvinai.

Although Shuvinai is not a patient of Dr. Allison Crawford, the psychiatrist who visits Kinngait regularly, Dr. Crawford knows her well. She observes of Shuvinai’s thought process: “I would probably describe [it] as tangential with a loosening of associations. Overall, her personality could be described as odd or eccentric … but already that is becoming stigmatizing.” Dr. Crawford comments on Shuvinai’s creative impulse: “One can easily see how … quirks in her thinking are also positive contributions to her artmaking and to underlying processes such as divergent thinking necessary for creativity.”

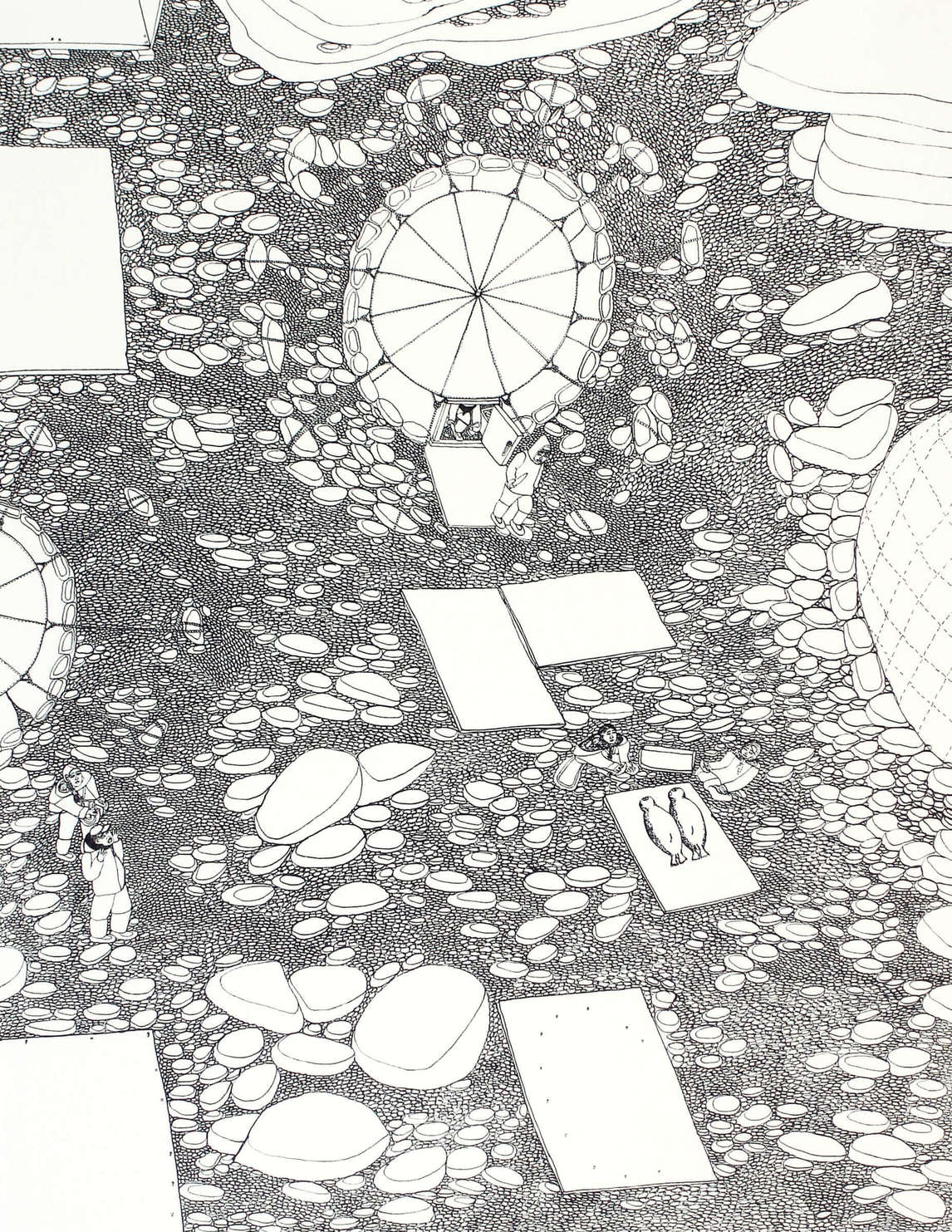

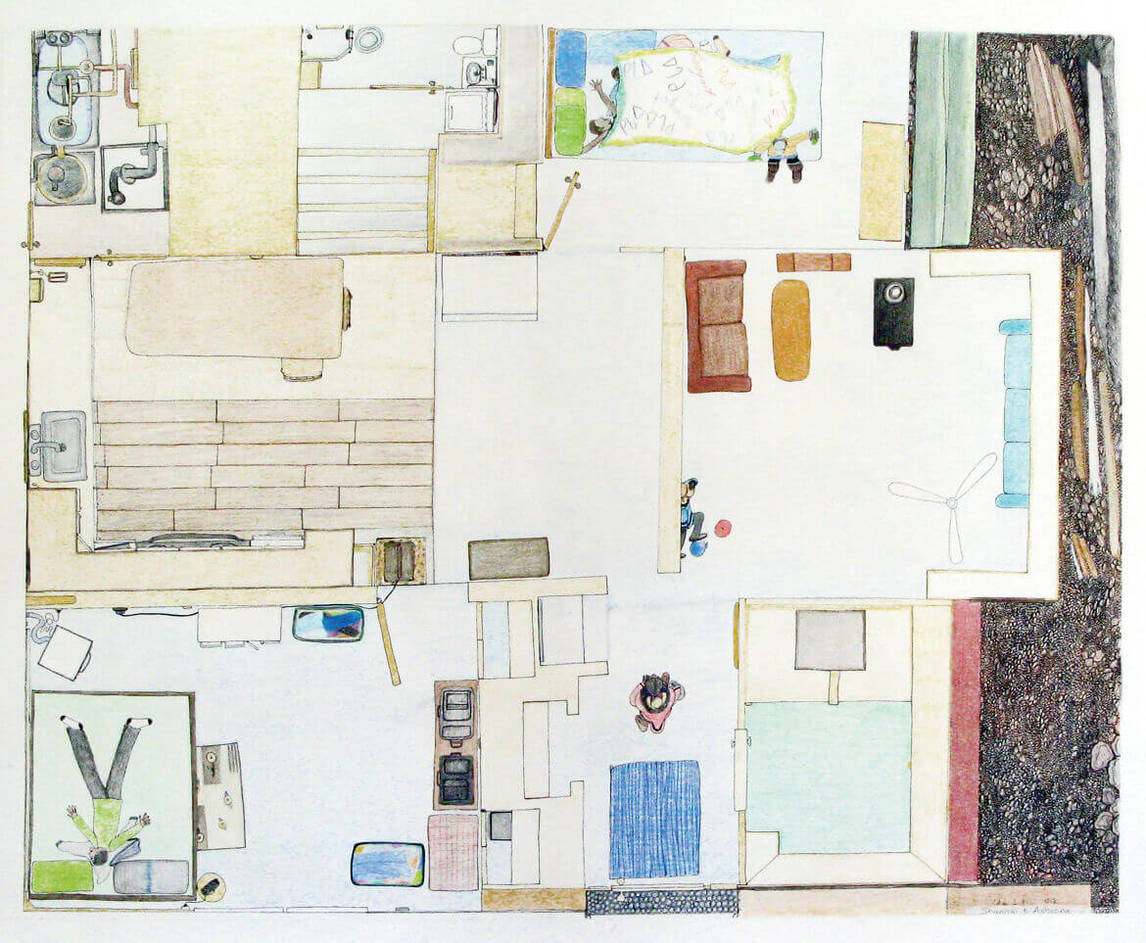

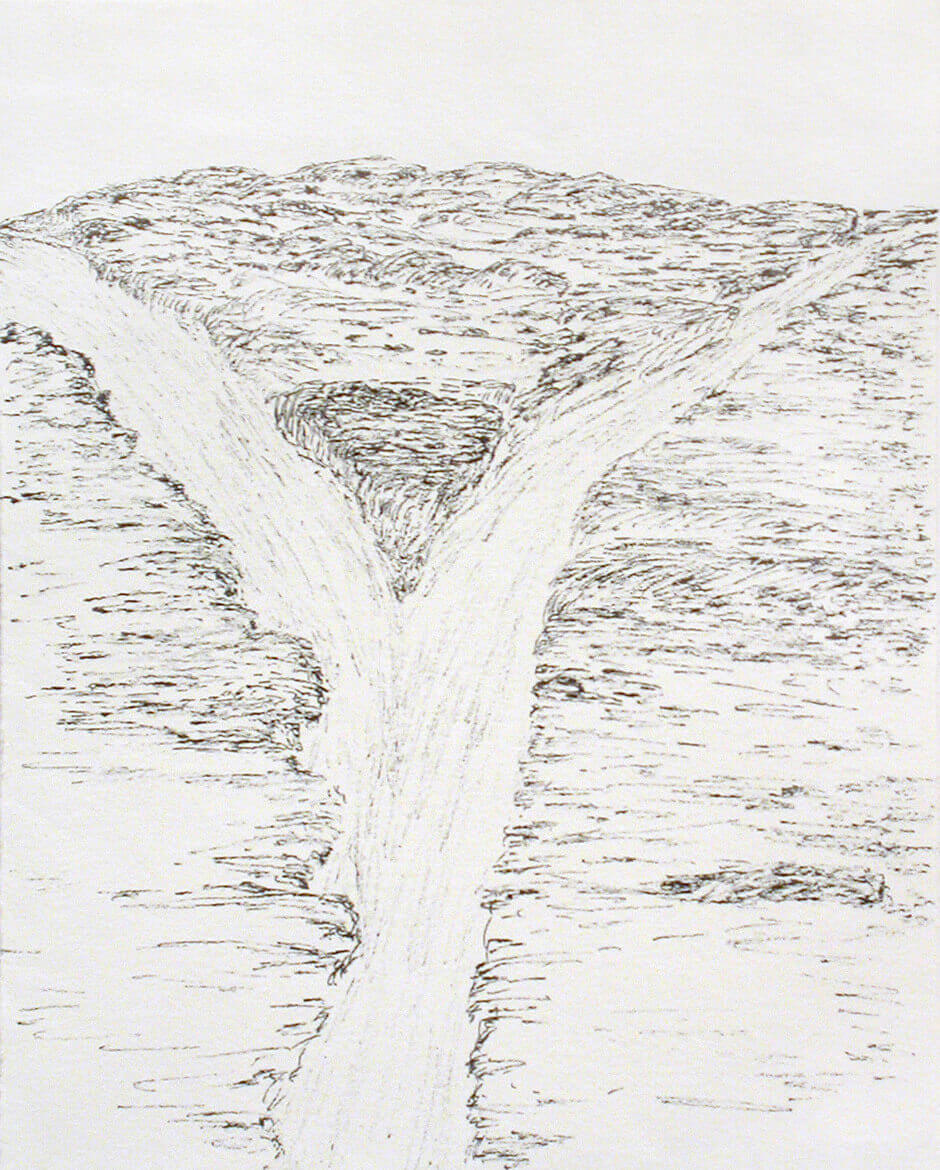

While Shuvinai is known to depict everyday scenes, as in Shuvinai’s World—At Home, 2012, she also found a way to channel visions and an altered sense of reality into her work. Rock Landscape, 1998, with its detailed rendering of a strangely distorted landscape, provides an early example. Drawings such as Composition (Two Men and a Spider), 2007–8, and Titanic, Nascopie, and Noah’s Ark, 2008, are but two of many drawings by the artist from the 2000s onward that show her melding everyday and fantastical elements in her work: the former includes human figures with hybrid features and the latter shows a winged polar bear and distortions of size, the giant squid many times bigger than the fishing boats it pursues.

Drawing from Roots

Shortly after her family’s return to Cape Dorset in the late 1980s, Shuvinai visited the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative for the first time, brought to its renowned drawing, printing, and carving studios by her younger sister Goota Ashoona, who had already begun artmaking. Goota thought that drawing would provide Shuvinai with income and help her to become self-reliant. Their famous aunt Napachie Pootoogook (1938–2002) encouraged Shuvinai to draw as well.

At the co-op Shuvinai had access to art materials, which she took home to experiment with. Although initially she made drawings at home, Shuvinai quickly became a regular at the co-op, a safe haven where she could work and stay warm. Like the two generations of Inuit artists before her, she received no formal training but certainly had ample opportunity to learn from her elders by watching them at work.

The co-op is a meeting place for Cape Dorset artists, many who no doubt had an impact on Shuvinai’s artmaking. The second-generation Inuit artists Napachie Pootoogook and Mayoreak Ashoona (b. 1946)—Shuvinai’s aunts—along with first-generation artist Kenojuak Ashevak (1927–2013), were particularly influential. Her cousin Ohito Ashoona (b. 1952) is a carver, and her younger brother Napachie also carves. Shuvinai has worked closely with her cousins Annie Pootoogook (1969–2016) and Siassie Kenneally (b. 1969), and over time they would begin experimenting with new ideas in their drawings.

Shuvinai’s first purchased works, the earliest of which date to 1993, are delicate, small-scale drawings, as in Waterfall, 1993–94. This early group of drawings, most of which are held in the Cape Dorset Archives at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, Ontario, also includes subject matter that offers intimations of later developments in her work, such as a flayed Christ and distorted landscapes.

Establishing Her Voice

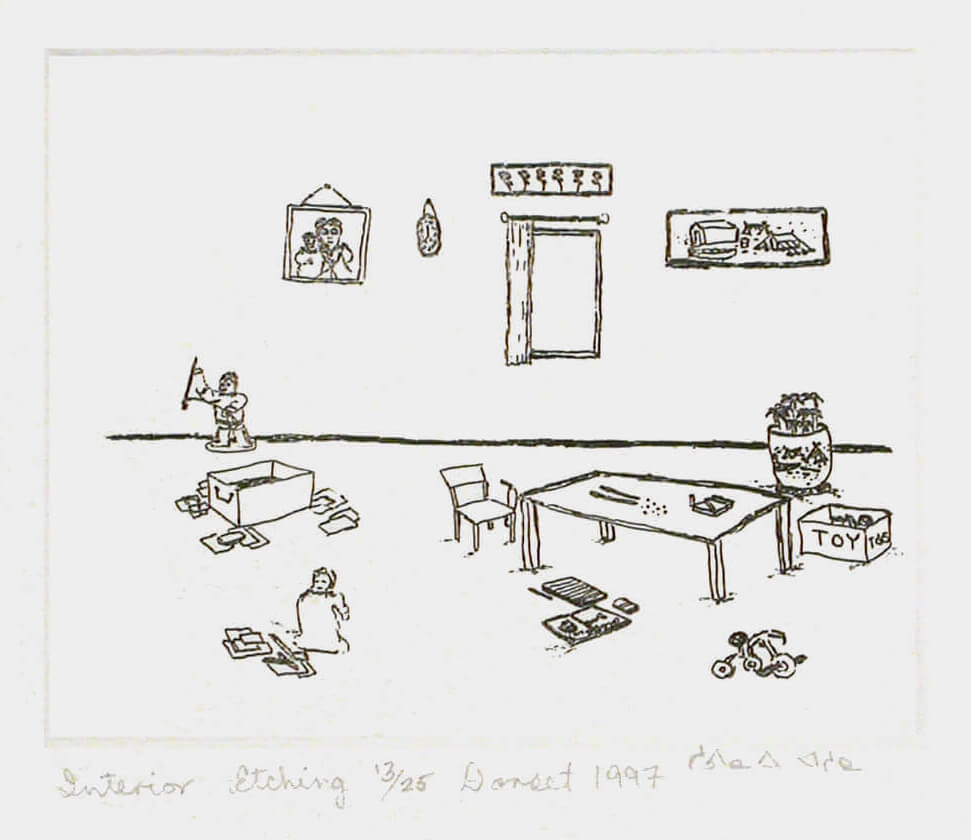

In 1997 two of Shuvinai’s drawings were adapted into prints (titled Interior and Settlement) for her initial inclusion in the Cape Dorset Annual Print Collection. Since then prints based on her drawings have appeared sporadically in the yearly releases. In 1999 the McMichael Canadian Art Collection held the first exhibition of Shuvinai’s work, in the notable show Three Women, Three Generations: Drawings by Pitseolak Ashoona, Napatchie Pootoogook and Shuvinai Ashoona.

In the early 2000s, when Shuvinai was in her early forties, her artwork exposed a new dynamism, as she gradually introduced colour into her work and began to explore her imagination and invent a personal iconography. Artist and photographer William Ritchie (b. 1954), manager of Kinngait Studios, encouraged Shuvinai to expand her subject matter, to mine her imaginings and historic stories from Inuit culture, popular culture, and Christian iconography. She began to set hybrid creatures and evocative human figures against highly detailed northern landscapes, which have come to be expertly realized by the artist, as is well demonstrated in Hunting Monster, 2015. Comparing this more recent work with an earlier drawing of a hybrid figure, such as Discombobulated Woman, 1995–96, reveals the artist applying colour, a heightened level of detail, and a different approach to negative space. The marked evolution in her artistic style points to an arduously developed artistic sensibility.

Shuvinai came to the broader attention of galleries and institutions in the South in the early 2000s, as signalled by the purchase of six of her landscapes in 2001 by the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa. As she became a prolific and original contributor to the Dorset stable of graphic artists, which includes Tim Pitsiulak (1967–2016) and Ningeokuluk Teevee (b. 1963), her drawings began commanding higher and higher prices. She likewise became the key earner for her extended family, which to this day relies on her tremendous talent and generosity.

International Artist

It was not until the mid-2000s that Shuvinai’s career began to take off, following the attention gained by her cousin Annie Pootoogook. Citing Jan Allen, curator Sandra Dyck notes, “The success of Annie Pootoogook—who had a solo exhibition at The Power Plant in Toronto and won the Sobey Art Award in 2006—convincingly demonstrated ‘the potential of daringly original contemporary Inuit art to capture the attention of global audiences.’ Pootoogook’s success broke ground for her artistic peers at home, too; the art world’s capricious gaze was now focused intently on Cape Dorset.”

Shuvinai’s and Pootoogook’s work was exhibited alongside the work of their cousin Siassie Kenneally at the Art Gallery of Alberta, Edmonton, in the 2006–7 show Ashoona: Third Wave, New Drawings by Shuvinai Ashoona, Siassie Kenneally and Annie Pootoogook. Feheley Fine Arts in Toronto held a solo exhibition of Shuvinai’s work in 2006, as did the Marion Scott Gallery in Vancouver in 2007, and Shuvinai travelled south for these shows. Her work has since been presented in several group exhibitions across Canada.

In 2008 Shuvinai worked with Regina-based artist John Noestheden (b. 1945) to create Earth and Sky, 2008, a gigantic banner that became part of a public art installation at the Basel Art Fair and was subsequently exhibited at the 18th Sydney Biennale in 2012 and at the National Gallery of Canada in 2013 at a major international exhibition of Indigenous artists, Sakahàn: International Indigenous Art.

In 2009 the Justina M. Barnicke Gallery at the University of Toronto paired two contemporary Canadian women artists—Shuvinai Ashoona and Shary Boyle (b. 1972)—in a two-person show, Noise Ghost: Shuvinai Ashoona and Shary Boyle. The show created a new conversation, challenging old assumptions about Inuit art; for example, that it should be a singular production depicting animals, birds, or fish or figures of hunters and mothers. Noise Ghost won the Ontario Association of Art Galleries Exhibition of the Year Award. Two years later Boyle travelled to the North for a three-week residency at Kinngait Studios, working alongside Shuvinai.

Their second joint exhibition, Universal Cobra: Shuvinai Ashoona and Shary Boyle, was organized by Pierre-François Ouellette art contemporain in Montreal in collaboration with Feheley Fine Arts in 2015. The two artists showed both individual works and a number of sensational collaborative drawings created at Kinngait Studios. Shuvinai’s repertoire included monsters and hybrid wildlife, hunters, massive icebergs, and women giving birth to planets. These collaborative works, as in Exhibition, 2015, and InaGodadavida, 2015, show an expanded use of imagery of the land around her, the artist’s insightful, playful mind turning logic on its head. With these drawings, Shuvinai has overturned notions that conscript Inuit art to particular kinds of representation, often promoted as “traditional.”

Shuvinai has enjoyed great success with her drawings, which along with her prints continue to be sought after by museums across Canada. In recent years her work has been selected for international exhibitions of contemporary art, including Oh, Canada: Contemporary Art from North North America in 2013 at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA), North Adams, Massachusetts, and Unsettled Landscapes: SITElines: New Perspectives on Art of the Americas in 2014–15 at SITE Santa Fe.

Shuvinai has been working daily at Kinngait Studios for more than twenty-five years. She is a major force in the development and success of the contemporary drawing practice now prevalent at the studio, and she has become a critical voice in Canadian contemporary art. In a wonderful article on Shuvinai in Vitamin D2: New Perspectives in Drawing, author Meeka Walsh concludes with words from Shuvinai: “‘I’m such a little person beside such a big universe.’ More than that, she is a little person creating a big universe.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements