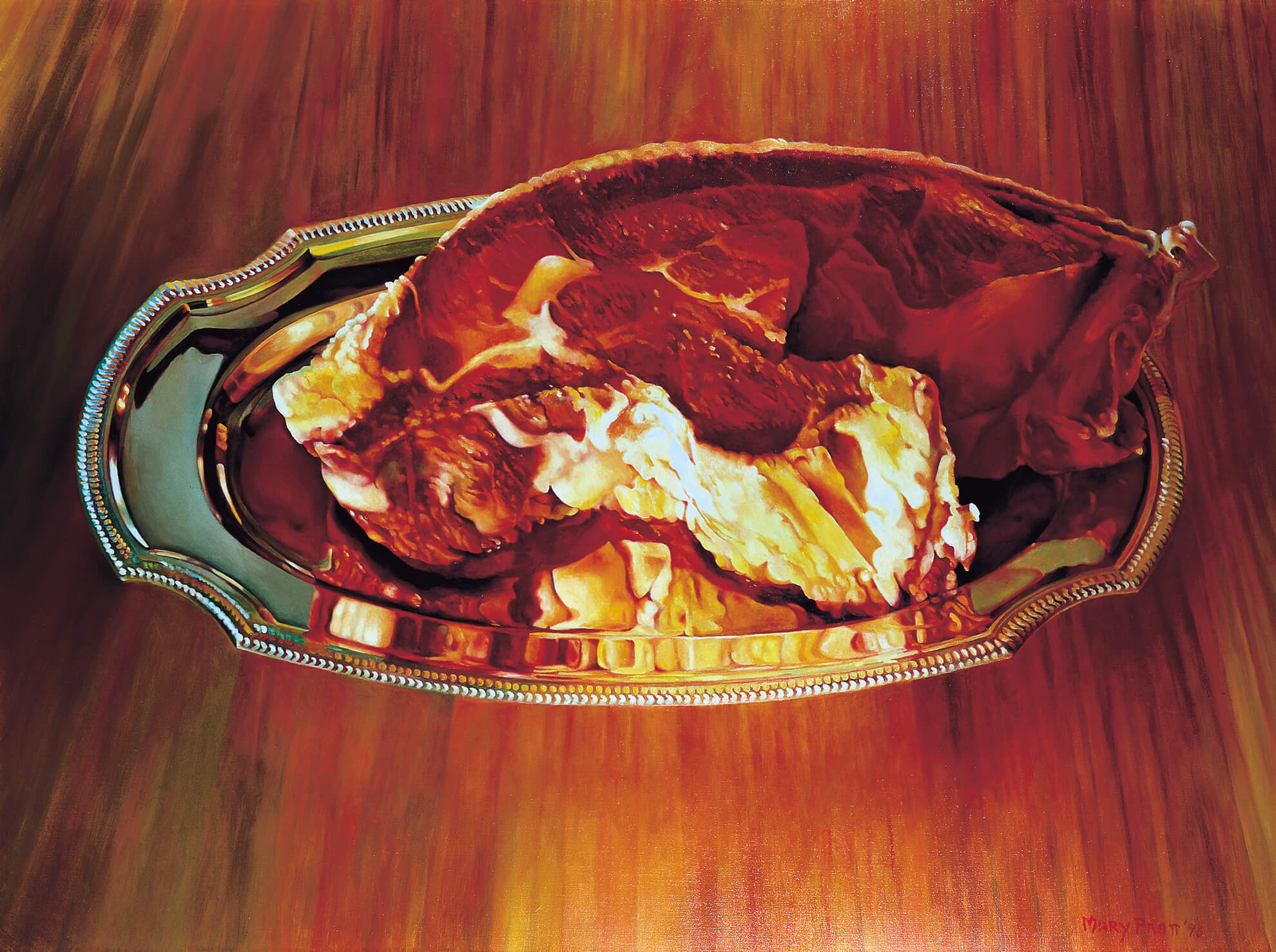

Sunday Dinner 1996

Mary Pratt, Sunday Dinner, 1996

Oil on canvas, 91.4 x 121.9 cm

Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, Halifax

Sunday Dinner is a simple image: an expanse of wooden counter, a thin silver platter, and, centrally, raw flesh—glistening red, and dappled with white fat. A slab of beef before it goes into the oven for roasting represents a brief moment, but one in which it is most evident that an animal has died, and for which a whole system of distribution, value, and work is deployed.

Mary Pratt always maintained that she chose her images because they were beautiful to her. Something caught her eye and she photographed it, and later, perhaps months or even years later, she would come to a photograph again and find something else beautiful about it. Robin Laurence writes, “She condemns the romanticizing of the still life by European painters, and strives for a quality in her own work which she describes as a ‘vicious reality,’ a quality she sees as particularly North American.” Pratt’s sense of that vicious reality often manifested itself in images of raw meat and fish, the blood and gore that accompany the preparation of a meal. Sacrifice always lurks in her work, because, as she said so often, “You do have to have a sacrifice before you have a party.”

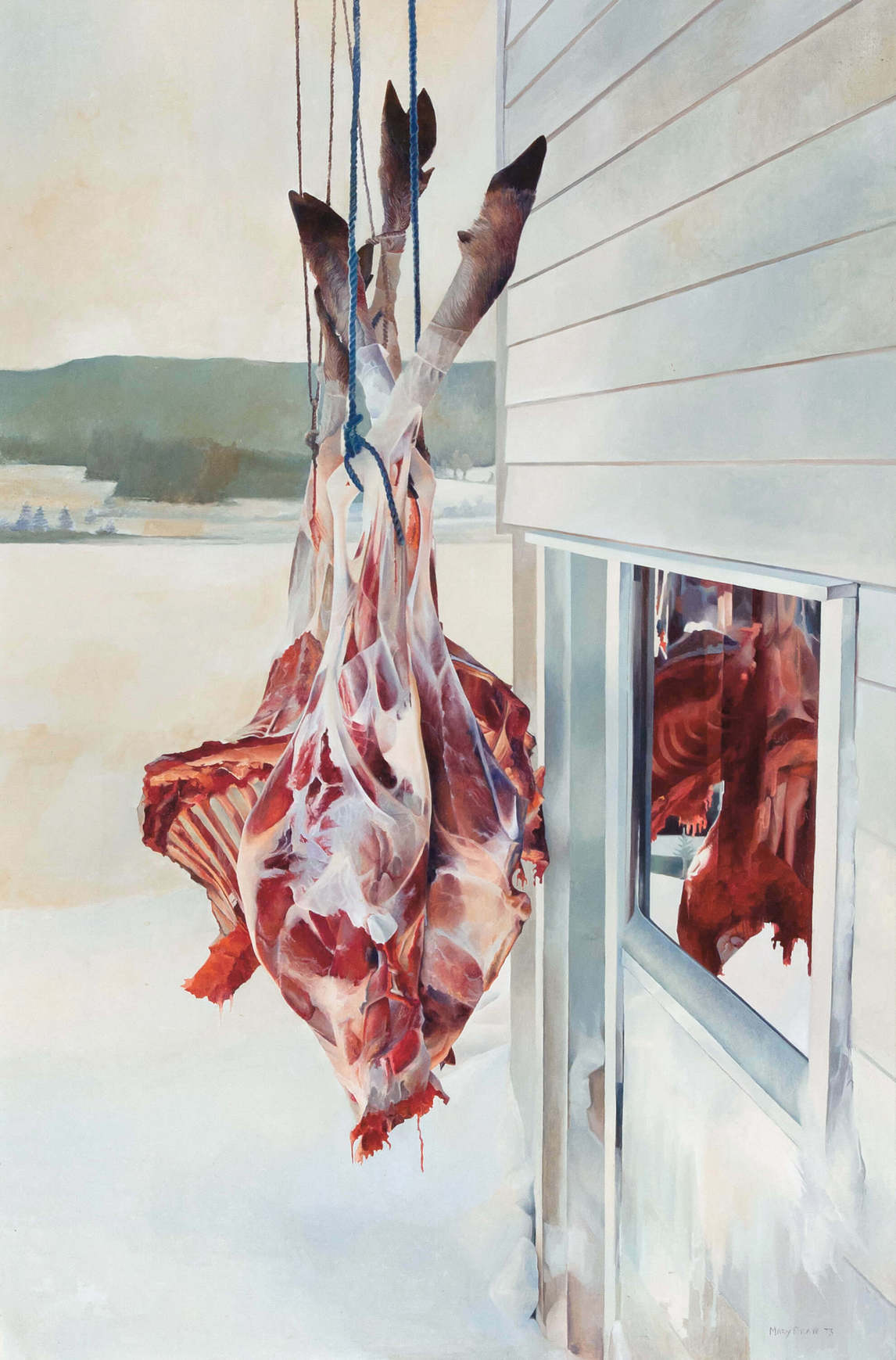

This is one of the few works in Pratt’s oeuvre of raw red meat, the others being her two depictions of moose, Service Station, 1978, and Dick Marrie’s Moose, 1973, which are very different in composition. The raw meat in Sunday Dinner has a blurry, out-of-focus appearance present in the original slide on which the painting is based. Typical for Pratt is the use of the silver platter, a signifier of the middle-class values represented by the whole idea of the Sunday roast.

The image is noticeably staged, as one wouldn’t normally put a silver platter in the oven, or carve a roast on it. This staging device, in fact, highlights that the silver has communion overtones, framing the meat as both symbol and object.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements