While apprenticing under master carver Naka’pankam (Mungo Martin), Bill Reid (1920–1998) began to understand the complicated visuality of Haida art. From it, he created an art form that spoke to the zeitgeist of Northwest Coast artistic traditions of the postwar period. From the early 1950s until the late 1960s, when he came into his own, Reid learned what it was to be a Haida artist. His creative life diversified to encompass a wide range of materials, tools, and techniques, but although Reid experimented with works on paper, he saw himself as a goldsmith, a jeweller, and a sculptor. Each project relied on, or resulted in, relationships with other makers, scholars, or art world professionals. How Reid approached making, and the quality of the relations he fostered in doing so, inform us of his vision.

Haida Visual Knowledge and Contact Zones

Bill Reid grew up in the Western world, far removed from Haida culture and its traditional ways of seeing and doing. As he came into closer contact with his Haida relatives, he began to understand his position of being in between cultures. Throughout the rest of his life he turned this in-betweenness to his advantage. Because Reid was an artist of skill and intellect, he became a critical conduit in articulating two distinct yet connected concepts: Haida visual knowledge and contact zones.

Visual knowledge, like medicine, hunting, storytelling, or architecture, is a form of intelligence that is learned, practised, and refined over time. Its purpose is to preserve memories and local knowledge, which are passed on through family and community. Understanding the land and its animals, fish, trees, waters, and rocks provides teachings that determine traditional values and ways of knowing and seeing. Visual knowledge is a tool applied by hunters, spiritual leaders, astronomers, and storytellers. For artists, however, their gift is to visualize through reflection, studying their culture’s visual logic and making a world from it. This knowledge is integral to Haida ways of seeing. A work such as Raven Rattle, c.1850, thus embodies distinct Haida visual knowledge of the animal.

Contact zones, on the other hand, are a condition of being in between. The literary scholar Mary Louise Pratt defines them as “social spaces where cultures meet, clash, and grapple with each other, often in contexts of highly asymmetrical relations of power.” As a result of Reid’s mixed ancestry, the artwork he produced reflected the complex dynamics of this condition. In many ways, a contact zone lived within Reid himself.

In the nineteenth century, Haida Gwaii embodied another kind of contact zone. The maritime fur trade had brought new wealth and new technologies. As a result, Haida visual knowledge began to see a shift in its traditional iconography. For example, argillite sculptures and silver jewellery were created with the European consumer in mind, as artists employed new motifs to picture the changing world around them. The artwork created in response to and as a result of these interactions is regarded as an apex of Haida cultural expression—today, museums around the world count these works among their holdings. Examples like Panel Pipe, c.1840, Dagger Handle, c.1850–80, and Figure, c.1850, show a mastery of medium seldom seen in the history of art. Yet, although these works remain unattributed because there exist no written records of the artists who created them, the great artistic tradition of the Haida is nonetheless unquestionable.

By the mid-twentieth century, however, at the onset of Reid’s career, a sinister reality of contact had already played out: European diseases, such as smallpox, had decimated communities. Legal and binding agreements, such as the pre-Confederation Douglas Treaties, had been nullified and replaced by the Indian Act. Lands had been annexed and the reserve system enacted, forcing people to abandon their traditional villages and ways of life. The Christian religion was legally enforced, while Haida visual knowledge became illegal through the enforcement of the potlatch ban. Children were taken from their communities and placed in residential schools in order to, in the words of Canada’s first prime minister, John A. Macdonald, “take the Indian out of the child.” These destructive colonial forces, among so many others, affected the health, well-being, and quality of life of the Haida Nation. The relations of power were in sharp imbalance. The style and technique of Bill Reid’s art must be understood as a product of this history.

Reid’s work is a reflection of those great Haida artists of the nineteenth century who depicted in their art a distinctly modernist sensibility: they readily broke with tradition by taking up new steel tools and new materials such as silver and gold, and adopted new motifs, such as the Europeans themselves, to create “art for art’s sake” to sell to visiting traders. Reid emulated one of the last exceptional Haida artists of that time, his great-great-uncle, master carver, silversmith, and artist Daxhiigang (Charles Edenshaw, 1839–1920).

In many ways, Reid’s laborious observational studies of Daxhiigang’s work, seen, for instance, in Reid’s xiigya (Bracelet) (made after Daxhiigang [Charles Edenshaw]), c.1956, were intended to obtain the skill necessary to pick up where his great-great-uncle had left off. Daxhiigang had established his reputation during this creatively exhilarating yet culturally assimilationist period. He innovated to adapt his practice in response to the new reality of his world, perhaps rendering Haida narratives even more forcefully in a bid for their preservation. As Bill McLennan notes, Reid saw his great-great-uncle’s work as “the epitome of nineteenth-century Northwest Coast art.”

Early in Reid’s career, the Kwakwaka’wakw artist Naka’pankam (Mungo Martin), who had experienced first-hand the destruction of Indigenous ways of life brought about by the Indian Act, showed him the importance of story and song as a way of remembering and maintaining tradition. Just as the cultural traditions of the Haida were suppressed, so Kwakwaka’wakw art, dance, and ceremony were banned until 1951. From Naka’pankam, Reid learned that the ancient narratives could be found in the tools he had inherited from his ancestors; in working with the tools as he engaged with Haida forms in his own work, he would come to better understand his cultural heritage. Furthermore, his own practice, the names he would give his works, and the stories that they conveyed through visual knowledge could represent the living history of the people.

The experience of working with Naka’pankam inspired Reid to continue his journey and understand the Haida way of seeing the world, which accepts that the past is always present and contained within oral traditions and visual knowledge. Whether through telling the tales of important mythological figures such as the Raven (Xhuuya), Nanasimgit, or Dogfish Mother, or spatializing specific events within the landscape, this crucial perspective continued to enlighten Reid. Over time he adopted the Haida way of seeing and came to depict its visual knowledge. In Reid’s mind, this knowledge had disappeared or was lying dormant and needed to be brought back to life. Through copying the work of the old masters, such as Daxhiigang, and working with artist Knowledge Keepers like Naka’pankam, Reid gained the skills, confidence, and perspective to produce novel work.

As he matured, Reid discovered the difference between producing works for institutions, such as the Haida Village, 1958–62, which he created for the University of British Columbia, and producing works for the living Haida community, best exemplified by Loo Taas, 1986. Art that was detached from the lived experience of the community was counter to Indigenous frameworks and ways of knowing. He came to understand that art was critical to the health of the Haida Nation. It called forth and brought to life the living, animate entity of Haida culture. Creating art for the potlatch, for example, was integral to giving life to the community. Reid knew that his artistic and cultural inheritance was essential to the continuance of Haida society and that artmaking was a functional component of society that required community participation. For Haida, art was a living, relational practice that could not be objectified. Like his predecessors, Reid understood the crucial distinction between art that was created to be sold in the contact zone, and art that was created to convey the unique visual knowledge of the Haida.

The Language of Formline

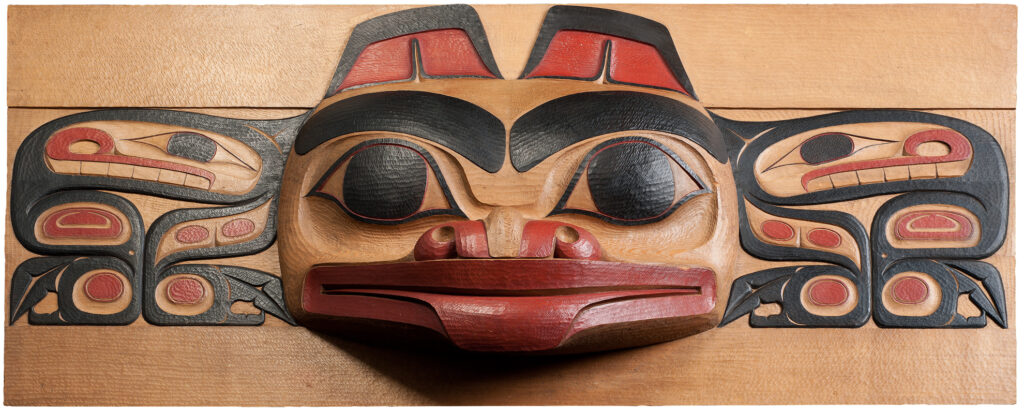

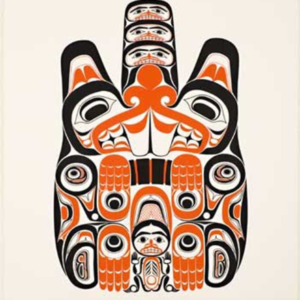

By the mid-twentieth century, ethnographic museum collections provided the primary access to Haida objects for those (mostly non-Haida) academics and artists studying Haida art and culture. Bill Reid was among those who pursued an understanding of Haida art in this way, as was the artist and art historian Bill Holm (b.1925). Holm analyzed the Northwest Coast style on the basis of three key elements: the formline, the ovoid, and the U-form. The formline is the broad band, usually black, that outlines main shapes, swelling and tapering as it moves. The ovoid is typically described as an oblong shape with curved edges and a concave bottom, though ovoids can take different shapes. The U-form is a vertically oriented half-form ovoid. In 1965 Holm summarized his findings in the book Northwest Coast Indian Art: An Analysis of Form. The language of formline that Holm developed was, and continues to be, widely embraced by English speakers, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous, as a way to communicate the formal qualities of Northwest Coast art.

Concurrently, Reid was pursuing his own research, studying collections of Haida art and producing artworks of his own in an effort to understand the logic behind Haida form. In 1964, for example, Reid made a silver box with a lid, which he titled The Final Exam. It was based on a bentwood box that would come to be included in the exhibition Arts of the Raven: Masterworks by the Northwest Coast Indian that Reid, Wilson Duff (1925–1976), and Bill Holm curated in 1967 for the Vancouver Art Gallery. At this time, Reid wrote “The Art—An Appreciation,” in which he reflected on the rules and conventions of Northwest Coast art, noting that its flowing lines turned in upon themselves to produce tension. He wrote, “Where form touches form, the line is compressed and the tension almost reaches the breaking point, before it is released in another broad flowing curve. . . . All is containment and control, and yet always there seems to be an effort to escape.” Reid observed that the dynamic power of Northwest Coast work came from the great artists who could skillfully develop their individual expression in concert with this rigid discipline. Throughout the 1970s, Reid made serigraphs such as Children of the Raven, 1977, further exploring the language of formline.

In 1975, at the invitation of American anthropologist Edmund “Ted” Carpenter, Reid and Holm co-authored Form and Freedom: A Dialogue on Northwest Coast Indian Art. This book records conversations between Reid and Holm about more than one hundred Northwest Coast art objects, including notable works such as Frontlet to a Headdress Representing a Thunderbird, c.1875–80, Headdress with Body Representing a Wolf, c.1930, and Ceremonial Dance Curtain (Thliitsapilthim), c.1880–95. Reid appreciated the complexities and differences that had been achieved in these forms. As Reid and Holm learned the language of the objects, they developed new interpretations. They began to see that, through their makers, the objects “assumed lives of their own.” Not only did they imagine that the objects could come alive, but Reid insisted that the objects were alive.

Around this time, Reid also came into contact with the French anthropologist and structural theorist Claude Lévi-Strauss, whose writing illuminated the relationship between myth and visual art. Both Reid and Holm were likely influenced in their thinking about artworks by Lévi-Strauss, who believed that masks “[could not] be interpreted in and by themselves as separate objects.” He maintained that stories and myths were part of a larger system, which the Haida had always believed. Reid and Holm had been searching for an understanding that would lead to a deeper discussion about the Northwest Coast art objects they were examining. The theories of Lévi-Strauss encouraged them to go beyond formalist elements and the purely visual, to also consider how the objects related to Haida myth systems and narratives.

It should not be overlooked, though, that Reid’s understanding of these things had begun earlier with the stories he learned from Henry Young (c.1871–1968) and Henry Moody (c.1871–1945). As Reid’s career developed, Haida approaches to making—in which pre-existing narratives were coupled with inheriting the rights and privileges to particular crests—remained critical. Reid re-articulated these in multiple ways over time. By doing so, he both honoured and transformed them, paying homage to ancestral origins while fostering a creative, contemporary present.

The Deeply Carved and Well Made

Bill Reid often used the phrases “deeply carved” and “well made” to describe the Haida art that inspired him. While visiting Skidegate in 1954, he had an opportunity to hold and examine two bracelets made in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century by his great-great-uncle Daxhiigang (Charles Edenshaw). He would later recount how these works profoundly affected him by saying they were “really deeply carved.” Doris Shadbolt (1918–2003) expanded on this idea, saying that Daxhiigang’s bracelets showed “the principle of energy firmly contained which underlies Haida art,” and that “design must carry the charge that invests the images with their life as form and hence their meaning, empowering them, in short, to be carved deeply into our consciousness.” Reid later remembered that after this experience, “the world was not really the same.”

While the term “deeply carved” could refer to etched lines literally being thoroughly incised into the surface of a worked piece, to Reid it had a more metaphorical meaning, closer to what Shadbolt describes. It concerns the profound connection a work has to share with Haida ways of making and living. This sensibility became embedded in Reid’s consciousness and began to inform all aspects of his life. “Deeply carved” came to be understood as a physical embodiment of traditional Haida values: care, formality, stability, and humanity. For Reid, a deeply carved work was one that was well made and reflected the living spirit of Haida visual knowledge.

In his later years, Reid was able to vividly recall his early yet tentative artworks and began to regard them as connected to Haida values. Because Reid was a goldsmith at heart, he required that even his large-scale works maintain the same surface qualities as a fine piece of jewellery. His deep admiration for Daxhiigang and Haida artistry of the nineteenth century inspired him to reach back in his own work “toward the great days of the past.” His studio desk became “an extraordinary site of cultural alchemy.” Beyond the connection to his ancestors, Reid also understood that his work was not only for human eyes—that “the gods see everywhere.” The notion that one would adapt a form to privilege only the human vantage point ran counter to Reid’s embrace of Haida cosmology, which retains an awareness of that which is omnipresent: the supernatural inhabitants of the world. This contrasted sharply with much other art of the 1970s and 1980s, which experimented with materials and tested the conventions of aesthetic beauty, with human perception firmly grounded at the centre.

To Reid’s eyes, exceptional artists produce both traditional and innovative artworks that are of high quality, or well made. This is an important distinction, because in the Haida language there is no word for “art,” yet it is possible to describe something as “well made.” At the core of his practice, it was Reid’s fundamental aim, as he put it, to produce a “well-made object, equal only to the joy in making it.” For him, joy came through celebrating the magical qualities of the materials with which he was working, innovatively employing the tools that connected him with his ancestors, and articulating narratives that honour the past and enrich the present. The deeply carved and well made testified to all these things. For Reid, they underscored an untranslatable Haida way of seeing, or what is commonly referred to in English as “art.”

The Apprenticeship Model

In the Western art world there is a model of apprenticeship that was developed in the middle ages whereby a master craftsman employs an inexperienced person as an inexpensive form of labour in exchange for providing food, lodging, and formal training in the craft. In Haida culture there is a different form of apprenticeship, one that is based on familial lineages or gifts from the supernaturals. A young person who appears to have an affinity for an art form works alongside an uncle, or someone within the person’s lineage, who has mastered that art form, thereby gaining the visual knowledge, skills, and ways of being needed to eventually fulfill the cultural role of the master. Today, the forms of apprenticeship may deviate from tradition, but the practice is still followed.

Lineages are extremely important in the Haida apprenticeship model because the content conveyed by the art form and the right to articulate it are owned and passed on through ancestral lines. Haida artists of Bill Reid’s era, however, were faced with the devastating effects of colonialism, which had prevented much cultural knowledge from being passed down. One way of overcoming this rupture for Reid was by copying works done by his great-great-uncle Daxhiigang (Charles Edenshaw), such as bracelets, dishes, and brooches, in order to learn what he might have been taught had he grown up alongside his relatives. This can be seen as a kind of apprenticeship in absentia—learning how the master made objects by attempting to do so oneself. However, the lived human connection was missing from this process.

Thankfully there was a willingness to share knowledge between First Nations, and Reid was able to apprentice in connection with living artists. Beginning in the 1950s he began working alongside Northwest Coast artists such as Naka’pankam (Mungo Martin) and Henry Hunt (1923–1985), whose approaches to making art would expose him to lived cultural practices. Naka’pankam, whose name means “Potlatch Chief ten times over,” was a distinguished master carver, designer, singer, and song-maker who had been raised in the potlatch tradition of the Kwakwaka’wakw culture. In 1957 Reid had the opportunity to carve part of a pole at the British Columbia Provincial Museum in Victoria (now the Royal BC Museum) under the direction of Naka’pankam for two weeks. Although this period was relatively brief, it gave Reid a taste of the interwoven quality of intact cultural production in Northwest Coast traditions. For example, Naka’pankam “sang all the while he was carving,” which for Reid, who believed in “a deep unity of all the arts, with music at their core,” was impressive and significant.

Between 1958 and 1962 Reid worked with another Kwakwaka’wakw carver, Doug Cranmer (1927–2006), his “other-side man.” The two carved and constructed the Haida Village. Cranmer had learned “everything he knew” from Naka’pankam, who had shown him how to design and how to carve without saying anything. Over the three and a half years that Cranmer and Reid worked together, each brought his individual skills to the task of developing an approach to the job. Reid was in charge of the project, which meant that in carving the poles he went up the right side while Cranmer went up the left, following what Reid was doing “like a machine.” Cranmer had to “[subdue] his own creative impulses in the interests of the project.”

While Reid was working on these large-scale carvings, he was also continuing to produce jewellery. As he became more established, younger carvers and jewellers worked and learned under him. For example, Haida carver Robert Davidson (Guud San Glans, b.1946) began working with Reid in 1966, at the age of twenty, and remained an apprentice for eighteen months. Importantly, in addition to teaching him technical skills, Reid articulated to Davidson what was possible for him as a Haida artist in the commercial art world, and introduced him to Wilson Duff and Bill Holm, fostering professional relations that lasted for years.

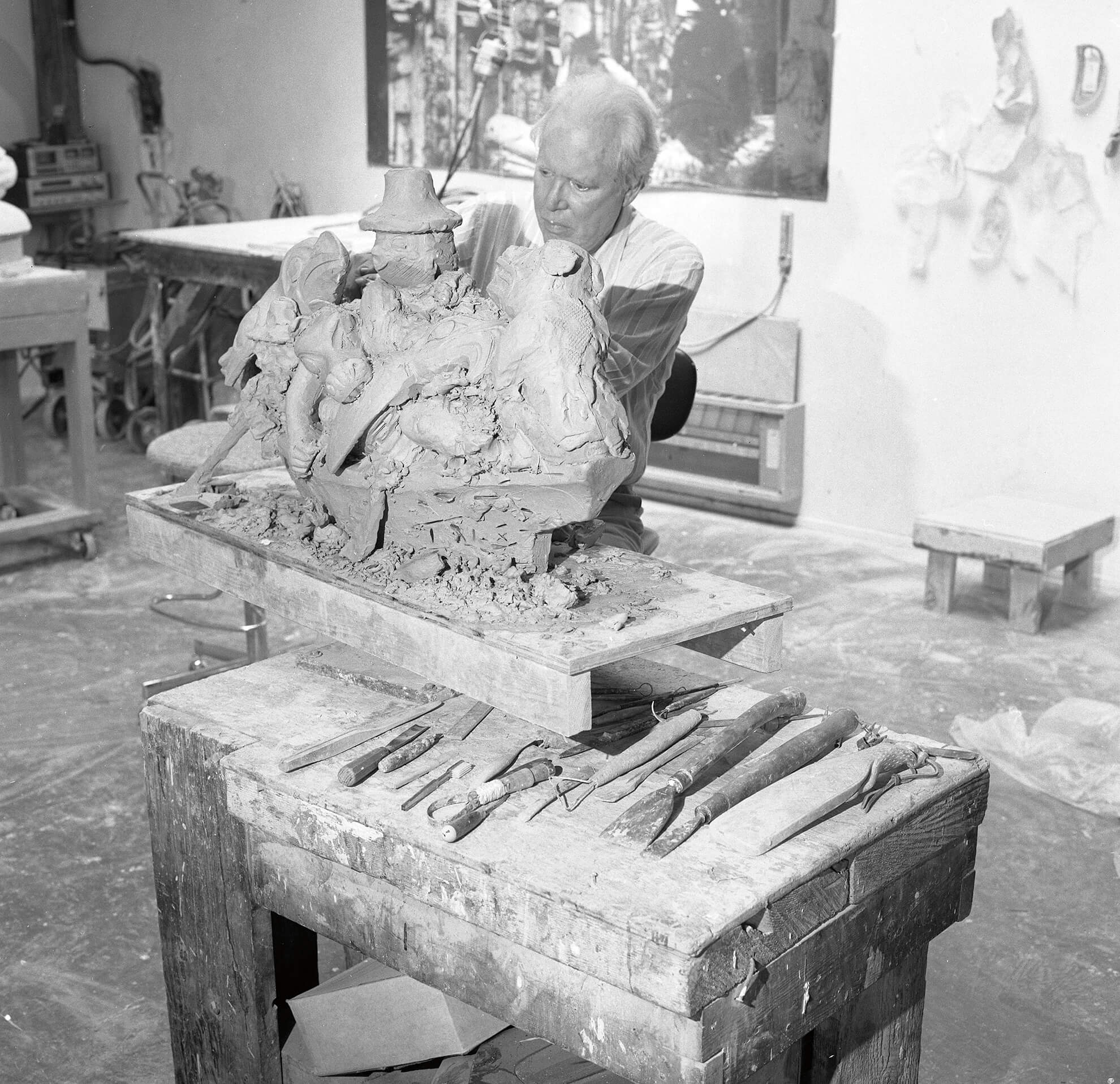

By the mid-1970s Reid was gaining broader recognition in the art world, and he began an extended period of intensive work on large-scale commissions and community-based projects. At the same time, his Parkinson’s disease was progressing and he became less able to produce work with his own two hands; nonetheless, he had a number of concurrent large-scale projects to manage. At this point, he adopted a role more akin to a “maestro conducting an orchestra.” He looked for skilled practitioners with whom he had an affinity, Haida and non-Haida, to contribute to every facet of the projects. Now Reid himself was in the position of a master teaching young apprentices. Beginning with The Raven and the First Men, 1980, and ending with Loo Taas, 1986, Reid needed and trained a number of sculptors. These included Haida artists Guujaaw (b.1953), Jim Hart (7idansuu, b.1952), Robert and Reg Davidson (b.1954), and Don Yeomans (b.1958), as well as non-Natives such as George Rammell (b.1952), who worked for Reid on fourteen sculpture projects from 1979 to 1990.

In the broader community, Reid’s practice had a major ripple effect on the work and opportunities available to young artists, particularly carvers of Haida heritage. Reid took much of his inspiration from the idea of giving back to the Haida community, but he was also inspired by thinking of art in terms of life. For decades he had befriended museologists and ethnographers who were often salvaging ancient, outmoded, or confiscated objects and keeping them within institutional walls. Reid, in contrast, saw art as being alive, especially because he was working in the company of so many artists. Loo Taas, the monumental canoe constructed in Skidegate, was a project that brought Reid’s vision to light. In an era of socially engaged art practice, Reid showed the world that Haida art has always been participatory.

Tools and Methods

Over the course of his career, Bill Reid developed a sophisticated relationship with his tools, and his ideas about them help us understand his methodologies and beliefs. He possessed some of the tools that had been made and used by his great-great-uncle Daxhiigang (Charles Edenshaw), such as his engraving tool dating from about 1880. For Reid, not only did these tools have an accumulated history and contain knowledge, but they also embodied the Elder’s spirit. Either the blade or the handle of the tool could be replaced, but never both at the same time, since this would result in “losing what the tool knows, which is its potential to work forward while possessing its accumulated past.”

Newly made tools, once approved, were initiated through the First Chip Ceremony, a ritual carried out in the presence of Reid’s studio team. It was expected that studio assistants and lead carvers would maintain each tool and keep it sharp, reflecting the intelligence and self-esteem of the carver. The notion was that “the sharpest minds kept the sharpest tools.” In contrast, “dull tools, like dull people, were considered a dangerous waste of time.” Reid’s favourite tool was the lipped elbow adze, which Naka’pankam (Mungo Martin) had introduced to him in the 1950s. In the 1960s Reid worked with a metallurgist to adapt this tool for his own practice, retaining the blade style but changing the functionality of the handle in order to undertake the fine detail work required of jewellery.

Reid used both his tools and tradition creatively: his methods “play[ed] with the boundary between Haida and non-Haida art.” In the eyes of George Rammell, Reid was both a goldsmith and a “culturesmith.” While working with Reid, Rammell noticed that carvers generally push or punch tools of European origin away from themselves, whereas most Northwest Coast tools emphasize the backstroke and ask the carvers to pull the tool toward themselves, much like the hand planes Japanese artisans use. Rammell writes, “According to Bill, this is a motion (untypical of Europeans) that provides a better response and intimacy not only while carving but also while making love. After painstakingly repairing Bill’s tools, I was finally getting the inside scoop on information that applied to my quality of life.” Here, a web of relations is revealed—how one approaches making must be integral and in tune with how one approaches every facet of life.

-contextual-1024x658.jpg)

Because Haida artists traditionally worked horizontally on works, such as poles, that ultimately would be raised into a vertical position, Reid employed this approach to develop his large-scale pieces. One example is Skaana—Killer Whale, Chief of the Undersea World, 1984—the method allowed him to remain at ground level, giving him easier access to the piece. He could also rotate the work and approach it from different orientations. Once the plaster pattern was made, the work was oriented in its vertical position and, in keeping with typical European methods, a scaffolding was built around it so that further refinements could be made.

Today, Haida artists are still actively using local materials such as cedar and argillite. The younger generation of Haida artists experiment widely and make use of newer materials such as paper, canvas, glass, and textiles, which are less expensive and longer lasting. Bill Reid remains unmatched in the realm of jewellery making. Yet it is Reid himself who set the stage for the impressive large-scale projects that have become so common a part of contemporary Haida expression.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements