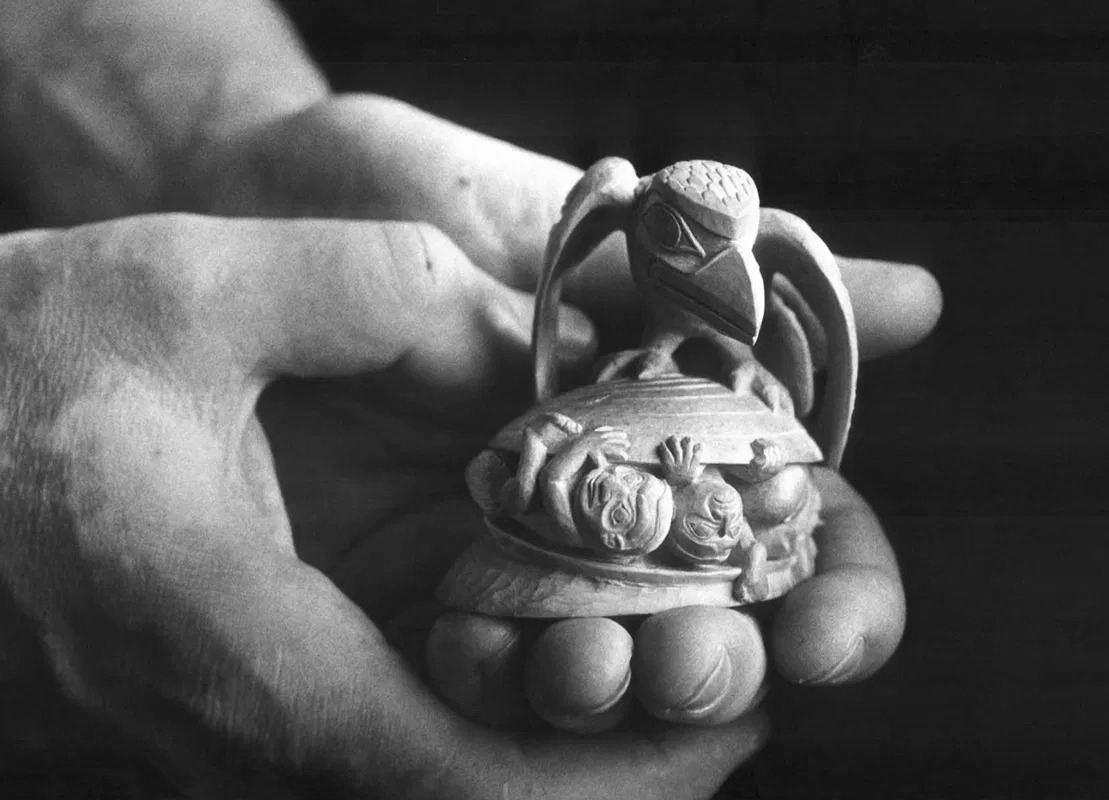

The Raven Discovering Mankind in a Clamshell 1970

Bill Reid, The Raven Discovering Mankind in a Clamshell, 1970

Boxwood, 7.0 x 6.9 cm

UBC Museum of Anthropology, Vancouver

One of Bill Reid’s most iconic large-scale works, The Raven and the First Men, 1980, first emerged as a diminutive yet fully formed masterpiece, cradled in the palms of his hands. That tiny boxwood sculpture, The Raven Discovering Mankind in a Clamshell, was carved in 1970, during the three-year period Reid was living in Montreal. Ten years later it would become monumentalized and take its place as a beloved cultural beacon in the University of British Columbia Museum of Anthropology in Vancouver. The narrative foregrounds the Raven (Xhuuya), the well-known Haida Trickster who created the archipelago of Haida Gwaii and its first humans. While multiple versions of this Creation story have been passed down, the one Reid interprets involves Raven releasing humans from a clamshell found on the beach. In doing so, Reid gave himself some creative flexibility, stating that it was “a version of the Raven myth for today, not for the time when it was created.” He saw the Raven as a “completely self-centred, uninvolved bringer of change,” who “through inadvertence and accident” represented the individualistic and diverse society of the current day.

The Raven Discovering Mankind in a Clamshell reveals a playful sense of humour. The characters emerging from the clamshell display a range of reactions to their new world, including wonder, fear, and perhaps even rejection. Curiously, Reid’s original boxwood miniature included a female human, as denoted by the labret (lip pendant) in her lip, yet she is absent from the large work. The latter more accurately aligns with the version of the story “The Raven and the First Men” that Reid and Robert Bringhurst rendered in their 1984 book, The Raven Steals the Light, in which females appear later in the story.

The fabrication of the large-scale The Raven and the First Men was in no way unproblematic, as the sculpture took Reid seven years to complete. Reid had initially requested a 3.05 metre cube of cedar from which to carve the work, but such a cube was almost impossible to obtain, and imperfections on the surfaces of the largest cedar cubes would have made them difficult to use. The solution was to fabricate a block of wood by laminating together 106 yellow cedar beams weighing more than 4,000 kilograms. Because Reid was simultaneously working on his Skidegate Dogfish Pole, 1978, and grappling with Parkinson’s disease, he needed to rely a great deal on assistants to carry out his vision.

Many younger Haida carvers became involved, such as Reg Davidson (b.1954), Guujaaw (b.1953), and Jim Hart (7idansuu, b.1952). Non-Haida Vancouver-based sculptors assisted as well. George Norris (1928–2013) was called in during the early stages to make a small-scale model in clay, cast it in plaster, and then carve a larger rough version in wood. George Rammell (b.1952) came in during the later stages to work on the emerging figures. Near the end, Reid contributed his finishing touches.

Whether in the miniature or the monumental, Reid makes visible the powerful domain of Haida narrative through the Raven. His enchantingly stubby body and beak do not detract from his imposing posture as he towers protectively over the clamshell and its inhabitants. Here, this Cultural Hero is in charge, and the human endeavours of art, history, and knowledge become part of his jurisdiction.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements