Loo Taas 1986

Bill Reid, Loo Taas, 1986

Red cedar wood, paint, 1520 cm (length)

Haida Heritage Centre at Kay Llnagaay, Haida Gwaii

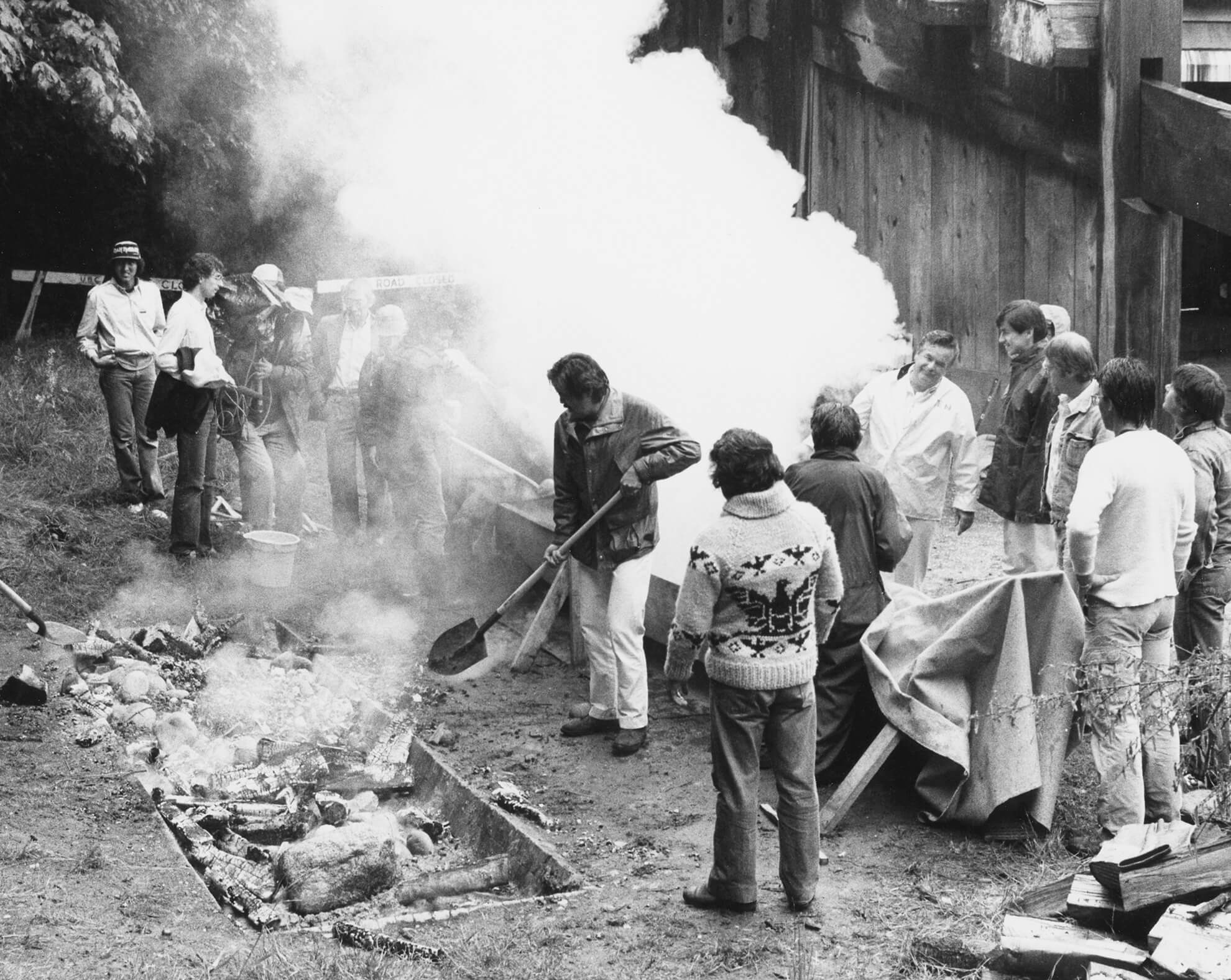

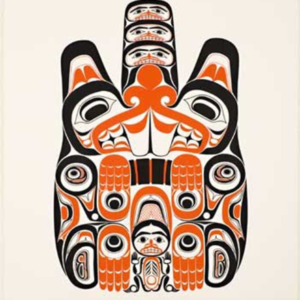

Loo Taas is a 15.2-metre-long red cedar ocean-going canoe commissioned for Vancouver’s Expo 86. She was designed by Bill Reid and built in Skidegate by a dedicated team of carvers led by Tucker (Robert) Brown over the winter of 1985/86. Her bow and stern feature a killer whale design created and painted by Haida artist Sharon Hitchcock (1951–2009). In response to Reid’s wish for her name to mean “Wave Eater,” Kaadaas gaah Kiiguwaay (Raven-Wolf Clan) matriarch Hazel Stevens established her Haida name from loo (wave) and taas (eat). Her story reaches back eight hundred years to when the 73-metre-tall tree that she was carved from began to grow in Haida Gwaii. The story of Loo Taas is still unfolding today as she continues to participate in important events in the Haida community.

Reid’s interest in canoe making was sparked by seeing a nineteenth-century Northwest Coast canoe painted by Daxhiigang (Charles Edenshaw,1839–1920) in storage at the National Museum of Man (now the Canadian Museum of History) when it was located in Ottawa. Inspired to learn more, he studied other examples and read books, gathering insight into this art form that for centuries had been at the heart of Haida culture but to him was still an enigma. Soon he began making a canoe himself in order to gain first-hand experience with the traditional processes and methods. In the early 1980s Reid started working with Haida carver Guujaaw (b.1953) and Kwakwaka’wakw carver Simon Dick (b.1951) to build a 7.5-metre inshore canoe. Shortly after came Loo Taas.

Loo Taas has a remarkable story. Community Elder and Haida activist GwaaGanad (Diane Brown) remembers: “It was really exciting. No one had made a big canoe in Skidegate in over 100 years. The day they steamed her open, the whole village came out.” Following her duties at Expo 86, Loo Taas was paddled back up the coast from Vancouver, following traditional trade routes and visiting many villages along the way. Each landing garnered a “royal welcome” that brought whole villages out to greet her and precipitated celebratory feasts. Segments of the journey were turbulent, but Loo Taas proved unfailingly seaworthy. Mysteriously, her homecoming to a “big knock-down” celebration in Skidegate aligned precisely with the Haida victory in the impassioned movement to protect the forests of Gwaii Haanas. In 1989 she was shipped to Rouen, France, and paddled by a delegation of Haida up the Seine River to be exhibited at the Musée de l’homme in Paris. And in 1998 she fulfilled Reid’s wish to carry his ashes to his final resting place: his grandmother’s once-populated Haida Gwaii village of T’aanuu. Still she goes on.

Reid began his career believing that the social patterns that were necessary to produce great Haida art were irretrievably lost to the past. Loo Taas gifted him the opportunity to witness the contrary. Every step of making and using her asked her people to know again who they are and to enact in the present the knowledge and ways of their ancestors. As Reid proclaimed, “Western art starts with the figure—West Coast Indian art starts with the canoe.” Together with his Haida relations, he called forth and brought to life an animate component of Haida culture critical to the ongoing health and beauty of Haida society. Like a prayerful poem, she was conjured by Reid, but her coming into being had in mind those who truly needed her.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements