Iljuwas Bill Reid (1920–1998) belonged to Raven-Wolf Clan of the Haida Nation. He is celebrated as one of the most significant Northwest Coast artists of the late twentieth century. While working as a radio broadcaster for the CBC, he established a highly regarded practice as a jeweller; he later became a sculptor of large-scale public works, all while discovering his Haida heritage through the art of his ancestors. Throughout his fifty-year-long career he was prolific as a maker and thinker, creating more than one thousand original works and writing dozens of texts that gave voice to his vision and the cultural issues of his day. A community activist, mentor, and writer, he is remembered as a passionate artist and an advocate for the “well-made object—equal only to the joy in making it.”

Introduction

My first encounter with Iljuwas Bill Reid was in the fall of 1978 at the first national gathering of Indigenous artists on Manitoulin Island. Many well-known and future artists attended. The second gathering, which I and Métis artist Bob Boyer (1948–2004) organized, was held the following year in Regina. It was during this time that I thought of the idea of interviewing some of the delegates. Bill graciously allowed me to interview him. I was both young and nervous. Over the next twenty years until his death in 1998 our paths would cross, though I was always in the presence of others and never alone with him again. My first encounter had been fortuitous and it left a lasting impression.

No artist has undergone as critical an assessment of their Indigenous identity as Bill Reid. His being and becoming Haida is significant. His career was a journey from his origins as “Bill Reid” to becoming Iljuwas, Kihlguulins, and Yalth-Sgwansang, as he joined the complicated political and cultural transformation of those he accepted as his people, the Haida. He lived at a point of intersection, within a contentious contact zone, and the development and reception of his artistic practice reflect these conditions of cultural entanglement.

Origins

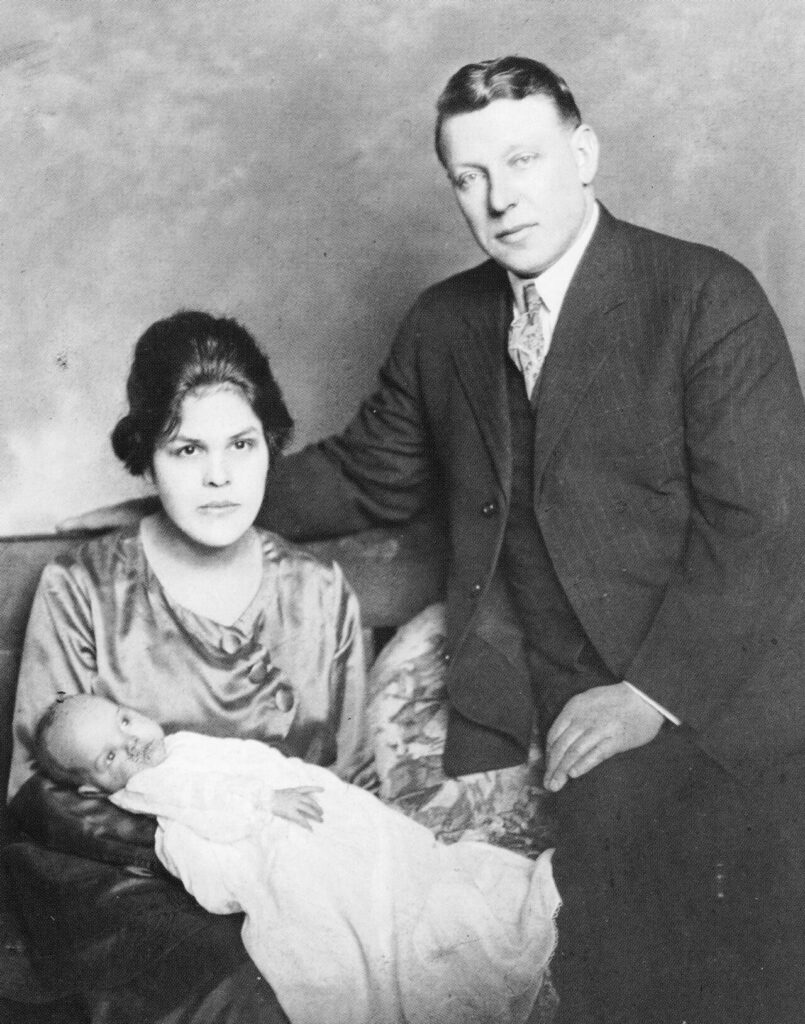

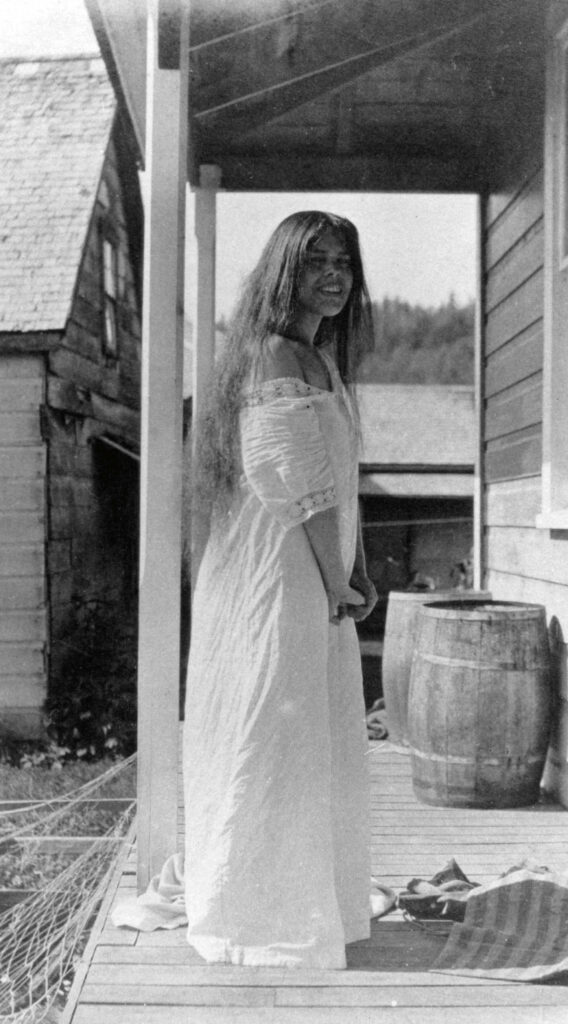

Bill Reid was born on January 12, 1920, in Victoria, British Columbia. His father, William Reid (1884–1943), was a hotelier at the time, managing an inn in Hyder, Alaska. Born in the Detroit area to a family with German-Scottish roots, William Reid left home at the age of sixteen to work on the railway. He eventually became a naturalized Canadian and, while managing a hotel he owned in Smithers, B.C., met Sophie Gladstone (1895–1985), Bill’s mother. Gladstone was born on Haida Gwaii and had grown up under the oppressive shadow of the Indian Act, which mandated that Indigenous children be taken from their communities. At the age of ten she was forcibly removed from her home and sent to the Methodist-run residential school Coqualeetza Industrial Institute, near Chilliwack, B.C. While she lived there as a student she was forced to speak English and was taught skills such as sewing, which were intended to assimilate her into mainstream Canadian society.

Sophie Gladstone’s marriage to William, a non-Native man, meant that she had to give up her “Indian” status. Bill Reid and his siblings were raised in an exclusively non-Haida setting; they did not learn the Haida language or their mother’s cultural traditions.

For Sophie Gladstone, the ripple effects of colonization and its mandate to erase Indigenous culture had taken a devastating toll. Later, when Reid became aware of how his mother had been stripped of her Haida identity, he said, “My mother had learned the major lesson taught [to] the native peoples of our hemisphere during the first half of this century, that it was somehow sinful and debased to be, in white terms, an Indian, and [she] certainly saw no reason to pass any pride in that part of their heritage on to her children.” He would come to devote much of his life and his work to reconnecting with his Haida roots and bringing honour and pride back to his mother and his people.

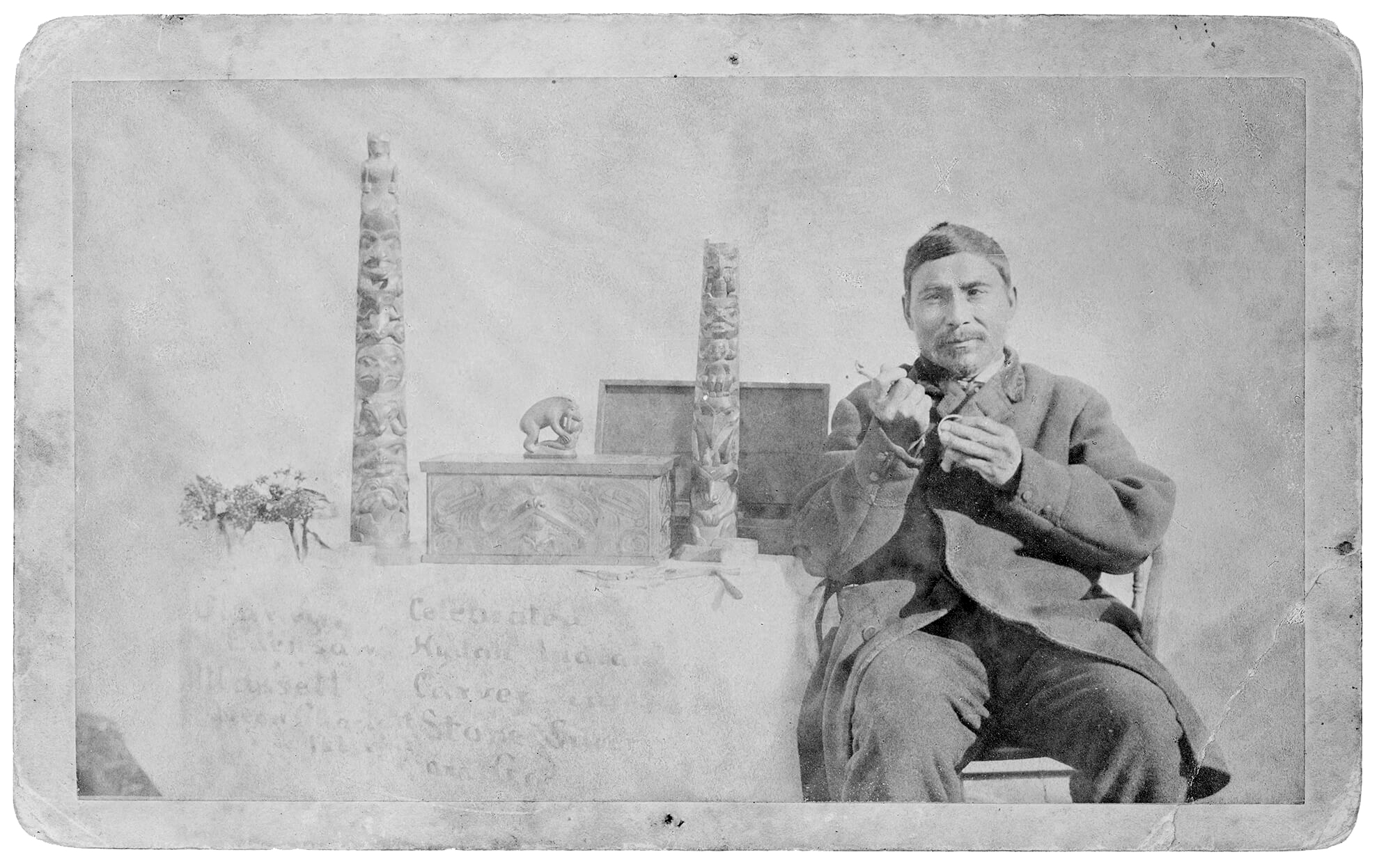

Reconnecting would mean learning about Haida cultural history, including the devastating diseases that decimated many villages during the nineteenth century. One surviving community was Skidegate, where Sophie Gladstone spent her childhood. Of the two great social groups found on Haida Gwaii, Sophie was born into the Kaadaas gaah Kiiguwaay, Raven-Wolf Clan of T’aanuu. Her father, Charles Gladstone (c.1877–1954), was the nephew of renowned Haida carver Daxhiigang (Charles Edenshaw, 1839–1920). Her mother, Suudahl (Josephine Ellsworth Gladstone), was from the ancestral village of T’aanuu. As he would come to know, Bill Reid was a part of something much greater than himself.

During the early twentieth century, T’aanuu was home to many totem poles that were selected for preservation and sold to museums. In a twist of fate, a pole collected by the ethnologists Marius Barbeau (1883–1969) and Charles Newcombe went to the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto. Reid encountered it around 1948 while he was searching for inspiration. By then called House 16: Strong House Pole, this masterwork with its familial connection was a gateway to his Haida identity and a key object that would inform his understanding of “deep carving.”

Early Life in Victoria and Northern Connections

Soon after Bill Reid’s birth, his mother, Sophie, returned to the North to be close to her husband, William. Yet once their second child, Peggy (later known as Margaret Kennedy), was born in 1921, mother and children returned to Victoria. They would stay until 1926. During this time Bill attended kindergarten and was taught by Alice Carr, sister to Emily Carr (1871–1945), in Emily’s future studio space.

Owing to the demands of his business, William split most of his time between Hyder, Alaska, and Stewart, B.C. From 1926 to 1932 the family lived in Stewart, where William could continue to operate a hotel, away from American Prohibition and anti-gambling laws that were affecting business across the river in Hyder. Bill attended school in Hyder for most of this time. As a result, between the ages of about six and eleven he was being taught an American curriculum by American educators. In Grade 6 he transferred to the school in Stewart.

In 1932 the Depression forced William out of business, and he had to close his hotel. Realizing that it was now up to her to support the family, Sophie moved Bill, Peggy, and their youngest sibling, Robert, who had been born in 1928, back to Victoria, where she established her own dress shop. She no doubt felt a connection with the city, as many Haida and other Indigenous peoples had frequented it since the Hudson’s Bay Company had established a post there in 1849. For these communities the city represented economic opportunity. For example, her great-uncle Daxhiigang (Charles Edenshaw) had often travelled to Victoria to sell his artwork. Soon after her arrival, Sophie and William separated, and Bill never saw his father again. Although father and son had never been particularly close, the two maintained sporadic correspondence until William Reid’s death in 1943.

Reid attended South Park Elementary School, where he had Canadian artist Jack Shadbolt (1909–1998) as a substitute art teacher in Grade 8; he later recalled that Shadbolt read poems and stories to the class and got them “drawing Kandinskys.” Reid went on to attend Victoria High School. Ira Dilworth was the school principal at the time, and he taught English literature and introduced music appreciation programs. An editor for Emily Carr’s writings, he was also the West Coast regional director of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), where Reid would later work.

Reid’s public school education reflected the norms of the day, which privileged non-Indigenous content. Although Reid later came to be known as a Haida artist, it is important to remember the breadth of his sources of inspiration. He later said, “The old people who made the great masterworks of the past were in their own terms universal men, and I think an approach to an art form that has as many layers of meaning, as I think the Haida has, requires a similar development of sensibilities towards the arts in general.” Throughout his career, friends and colleagues witnessed Reid’s alignment with this inclusive approach. Reid’s education and the cultural setting in which he grew up formed an important foundation for his practice.

During the 1936–37 academic year Reid was enrolled in a general arts program at Victoria College, but he did not graduate. Instead, he experimented with his natural talent for public speaking and volunteered as a radio announcer at CFCT in Victoria. A year later he was offered a paid position at a station in Kelowna. In time, Reid’s eloquent speaking voice brought him work at commercial stations in Ontario and Quebec before he joined the CBC in 1948.

In his early twenties Reid made the effort to visit his ancestral home of Skidegate for the first time since he was a baby. He yearned for connection with his relatives and, to some degree, with his Indigenous identity; he later noted that “in turning to his ancestors, in reclaiming his heritage for himself, he was . . . looking for an identity which he had not found in modern western society.” At this time most people of Indigenous ancestry could not embrace their heritage. The federal and provincial governments had done everything they could to systematically eradicate the continuation of traditional Haida ways. In spite of this, the visit was prophetic. In Skidegate, Reid reunited with his maternal grandfather, Charles Gladstone, a traditional Haida silversmith who had learned from his uncle, Reid’s great-great uncle, the renowned artist Daxhiigang. For the first time, Reid had the opportunity to see and handle Daxhiigang’s personalized engraving tools.

Reid was also introduced to Henry Moody (c.1871–1945) and Henry Young (c.1871–1968), two Haida historians and carvers in their seventies who upheld Haida traditions in their work. Young, in particular, made Reid aware of “the old myths with their element of time folding back on itself while it loops into the present and rolls into the future.” The Elders’ insights were based on the ancient narratives that live on in the culture through stories, tools, practices, names, and visual knowledge. This powerful idea shaped Reid’s view of the Haida concept of time. While European-based notions of time were linear and saw the past as forever lost to us, the Haida understood time as a cyclical condition in which ways of being could be re-energized. The past was always present, and in turn the future always connected to it. Haida visual knowledge, as seen through the example of these Elders and their works, fostered a sense of possibility and, eventually, optimism in Reid. All was not lost.

Broadcasting and Jewellery Training in Toronto

Now in his mid-twenties and still not quite fixed on his future goals, Bill Reid took up work in a number of commercial radio stations in eastern Canada, and later in Vancouver. He was inducted into the Canadian military, where he trained for a year. During this time, in 1944, he married his first wife, Mabel van Boyen. The couple moved to Toronto in 1948 when Reid landed a position as a radio news announcer with the CBC. While there, Reid attended goldsmithing classes at the Ryerson Institute of Technology (now Ryerson University). The school was near his CBC office, so he could attend classes during the day and continue broadcasting at night.

Reid trained in classic European jewellery-making and metalworking techniques. He also learned to experiment with three-dimensional forms by working a wire with a pair of pliers. Outside of class, Reid was influenced by the American modernist jewellery movement (active c.1930s–1960s), to which he was exposed through magazines such as California Arts and Architecture and Craft Horizons. Inspired by the British Arts and Crafts movement, American modernist jewellers prided themselves on creating handmade and typically one-of-a-kind pieces. Reid biographer Doris Shadbolt (1918–2003) writes that at this time, Reid “envisioned a future as a contemporary jeweller like Margaret [De Patta],” making unique pieces.

Upon completing his courses, Reid went on to work at the Platinum Art Company in Toronto. Later in life he would describe this as the only “real education” he had ever had. Working for “tough-minded Germans,” he carried out tasks that he perceived as “pretty chintzy stuff for such an accomplished jeweller as myself,” only to have his demanding boss throw his work into the scrap heap. This was a European-style apprenticeship during which Reid “began to learn something about the jewellery trade.”

Jewellery design became Reid’s main preoccupation at this time. Pieces he made included a Victorian-style ring for his mother and modern-style silver brooches based on the human figure, as well as marine and flower motifs. Other works he made included geometric pieces of jewellery set with semi-precious stones. Few of these early jewellery works, from what Martine J. Reid (b.1945) calls his “Pre-Haida” period, were authenticated with a stamped mark or engraved signature.

In his spare time, Reid studied the range of objects on display at the Royal Ontario Museum. In particular, he was drawn to the carved Haida pole in its main stairwell, which he discovered originated from his grandmother’s village of T’aanuu. Although he did not yet understand the Haida visual language, with his jeweller’s training complete he began to experiment by making a Haida-style bracelet, similar to the ones he remembered his maternal aunt wearing during her visits to Hyder and Stewart, where he had spent part of his childhood.

“Hooked” on Haida

In 1952 Bill Reid moved back to Vancouver with his wife, Mabel, and their newborn daughter, Amanda. He quickly set up a jewellery-making workshop and began selling small pieces to friends, though he also continued to work as a radio announcer for the CBC. During these years Reid interacted more directly with the Haida community. In 1954 Reid and Mabel adopted Raymond Cross (also known as Raymond Stevens, 1953–1981), the son of Haida and Nisga’a parents.

When news came of his grandfather’s death in 1954, Reid returned to Skidegate. There he found a half-finished bracelet on his grandfather’s workbench and completed it in time for the funeral. In another equally profound moment, he encountered two gold bracelets by Daxhiigang (Charles Edenshaw); for Reid, “the world was not the same after that.” Reid began to understand his artistic and cultural inheritance and his responsibility for its continuation. These bracelets became integral to his practice and study of Haida forms. In each art object he began to see “a frozen universe filled with latent energy.”

At this point Reid became “hooked” on Haida. He studied museum collections and read publications, searching for designs that he could copy. For example, Alice Ravenhill’s 1944 book A Cornerstone of Canadian Culture contained a Haida design of “the man in the moon,” which Reid copied for his Woman in the Moon Pendant/Brooch, c.1954. Inspired by Daxhiigang’s work, Reid studied examples, borrowed designs, and developed works that expanded on Haida traditions and adapted to contemporary conditions, just as Daxhiigang had done in his time. A bracelet Reid created in 1955 emulates the work of Daxhiigang.

Reid returned to Haida Gwaii on two occasions during the 1950s to join expeditions to salvage totem poles for preservation. Reid did not know at the time that in traditional Haida culture the eventual decay of poles was understood to be part of a natural cycle and leaving them in their original location respected the integrity of the culture. The desire to preserve the poles in museums was indicative of Eurocentric values. The expeditions that Reid joined perpetuated the “salvage paradigm,” an approach in which a dominant culture “rescues” the material remnants of a non-dominant culture that is assumed to be inevitably “dying.” Within Reid’s lifetime these methods and attitudes came to be questioned by many cultural practitioners.

In 1954 Reid joined his first “rescue” mission to his grandmother’s village of T’aanuu (T’aanuu Llnagaay) and to Skedans (K’uuna Llnagaay), with Wilson Duff (1925–1976), Jimmy Jones, Roy Jones, and three other people from Skidegate Mission. The team removed three poles from each village, cutting some of them into sections to manage their shipment. Three were delivered to the University of British Columbia, and three went to the British Columbia Provincial Museum in Victoria (now the Royal BC Museum). In 1957 Reid, as a “descendant of the Haidas and representative of the CBC,” joined a second pole-salvaging mission, this time to Ninstints (Nans Dins, SGang Gwaay Llnagaay) on Anthony Island (SGang Gwaay). The team included anthropologists Wilson Duff, Harry Hawthorn (1910–2006), Michael Kew, Wayne Suttles, cameramen Bernard Atkins and Kelly Duncan, writer John Smyly, and a Haida crew consisting of Roy Jones, Clarence Jones, and Frank Jones. The expedition was recorded to later become the CBC film The Silent Ones, which Reid narrated. With the financial support of the lumber baron and philanthropist Walter C. Koerner, the salvaged poles were again distributed to the same two provincial museums.

In 1957 Duff invited Reid to Victoria to spend ten days carving a replica of a Haida pole under the direction of seventy-eight-year-old Kwakwaka’wakw master carver Naka’pankam (Mungo Martin, 1879–1962). Up until then, Reid had focused on small-scale metal works. Naka’pankam introduced him to the lipped adze, adapted from the ship carpenter’s adze. Though Reid worked with Naka’pankam for only a short time, the experience exposed him to the master-apprentice method of learning integral to Haida culture. He was profoundly influenced by Naka’pankam and came away from their meeting committed to upholding the stories and traditions of his culture.

Reid now began to understand the network of relationships in which individuals share responsibility in respecting and maintaining Haida cultural traditions, and the functional role played by living artworks. Yet it would be another two decades before he would engage in a culturally relevant act such as a pole raising. Nonetheless, the experience of working under Naka’pankam propelled Reid on to his first monumental carving project.

In 1958 Harry Hawthorn invited Reid to the University of British Columbia to restore some totem poles, including those Reid had helped remove from Haida villages during the “rescue” missions. Reid made the decision to leave his CBC job for good to pursue this invigorating opportunity to carve. When the commission began, however, it became clear that respecting the integrity of the old poles and instead carving new copies would make a greater cultural contribution. This led Reid to design and construct a portion of a Haida village in collaboration with Doug Cranmer (1927–2006), a young Kwakwaka’wakw carver. Completed in 1962, it included two traditional house structures, seven poles, and several other significant wood carvings, among them Wasgo, 1962. Known on its completion as Haida Village, this was Reid’s first major commission.

Growing Recognition

Bill Reid’s career was in transition and his personal life followed suit. His divorce from Mabel van Boyen in 1959 was followed by a short-lived marriage to Ella Gunn that lasted two years, ending in 1962. Newly single, Reid set up his own jewellery business on the second floor of a building on Pender Street in downtown Vancouver and began making art and jewellery full-time. This became a hangout spot and the place where many of Reid’s master-apprentice relationships began, most notably his friendship with a young Haida carver, Robert Davidson (Guud San Glans, b.1946). The two became close, living and working together for a time and collaborating for many years.

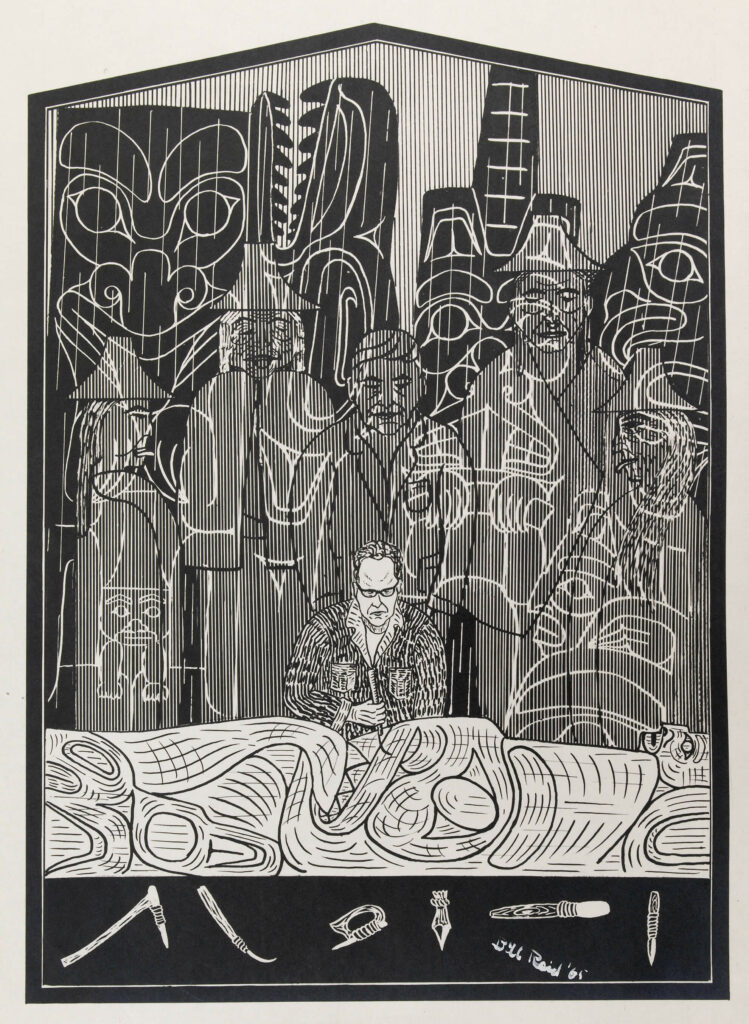

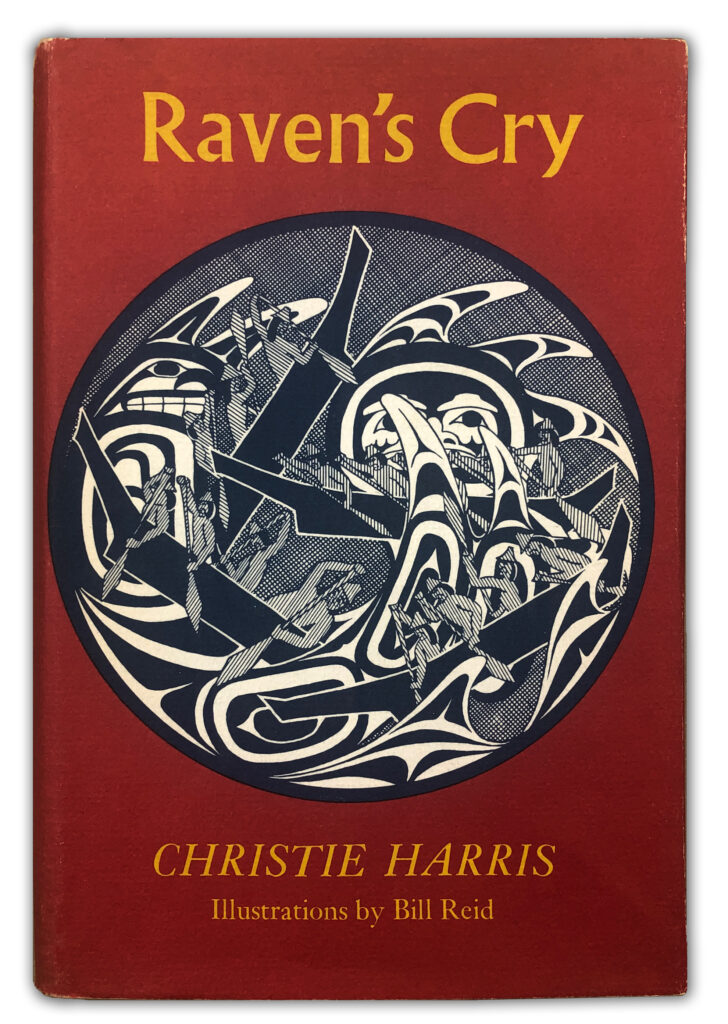

In the 1960s Reid began to draw. He provided illustrations for Christie Harris’s 1965 children’s book Raven’s Cry—a fictionalized account of Haida history that includes a character based on Reid as the successor of renowned master carver Daxhiigang (Charles Edenshaw). One of Reid’s illustrations features him at work carving a pole while the ghosts of his forebears tower over him from behind. The work reveals a rare moment of visual self-reflection.

During this time Reid had become known as an “unusual person, someone who had a root by blood in the Haida culture, but also critical distance from it.” Any such distance was short-lived. He quickly identified with the crucial responsibility involved in presenting and handling art with cultural and spiritual significance. As a person whose ancestry and creative practices bridged two vastly different cultures, Reid awakened to the problem of grouping all Indigenous peoples together. For Expo 67 in Montreal, Reid was among more than a dozen Indigenous artists commissioned to exhibit at the Indians of Canada Pavilion. Contributors included Alex Janvier (1935–2024), Carl Ray (1943–1978), and Norval Morrisseau (1931–2007). Reid turned down the commission because the pavilion’s advisory committee requested he carve a generic-style pole, but such a pole simply did not exist. He noted: “If you hire a Haida carver you get a Haida pole. If you hire a Kwakuitl carver you get a Kwakuitl [sic] pole. . . . If you want a bastard pole, draw your own conclusions.” Instead, Reid created a gold box with an Eagle standing on its lid—the first of many gold boxes—and exhibited it in the Canadian Pavilion.

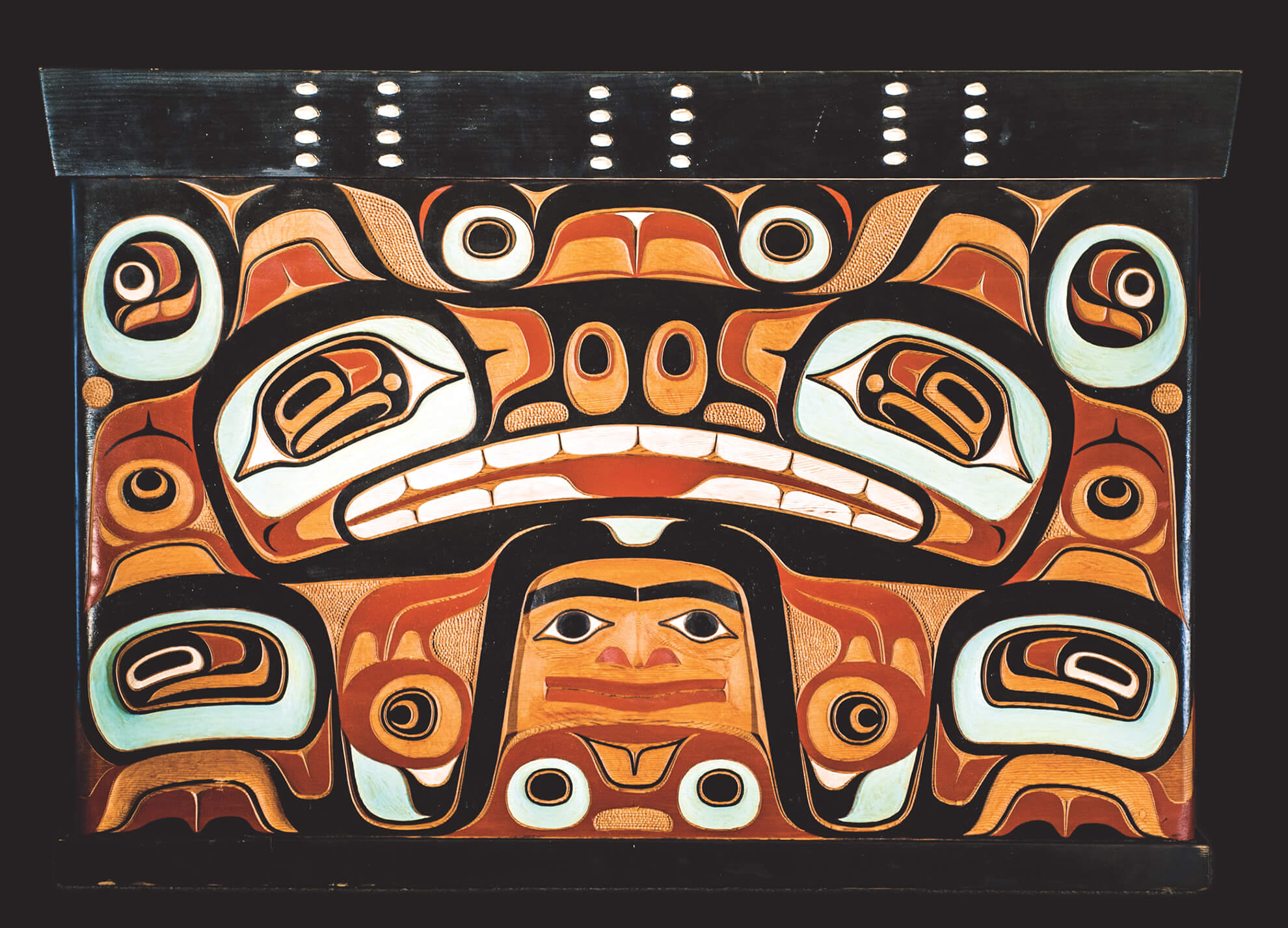

In 1968 Reid was commissioned by the British Columbia Provincial Museum in Victoria (now the Royal BC Museum) to produce Cedar Screen, a large, double-sided carved panel depicting a fisherman among entangled mythic Haida characters. It marked an artistic and personal departure for Reid and the beginning of his “Beyond Haida Phase.” A CBC documentary made at the time shows Reid narrating the stories contained within Cedar Screen and expressing his love for Victoria. Reid was preparing to leave British Columbia and was nostalgically bidding farewell to the West Coast.

Having received a grant from the Canada Council, Reid moved to London, England, for a year, where he developed his goldsmithing techniques at the London Central School of Design. While there, Reid continued working on modernist design themes that he had started to explore earlier in the 1960s. He began making Milky Way Necklace, 1969, a stunning gold and diamond masterwork that revealed his growing interest in carrying Haida ways of seeing into contemporary, abstract forms.

Montreal Years

When Bill Reid returned from London in 1969 he chose to live in Montreal, a cosmopolitan city that was energized by Expo 67. The three years he spent there proved to be an important period. The distance from his family and the West Coast scene clarified and intensified his focus. By now Reid’s technical skills were strong and highly controlled, allowing him to employ a range of materials—including alder wood, argillite, gold, and abalone—in the jewellery and sculptures he made. The works he produced at his solitary workbench would set in motion the next stage of his career.

During this time Reid created two miniature sculptures that would later evolve into monumental public works in Vancouver. These were The Raven Discovering Mankind in a Clamshell, 1970, a small boxwood carving that became the model for The Raven and the First Men, 1980, at the University of British Columbia Museum of Anthropology in Vancouver, and Killer Whale Box with Beaver and Human, 1971, a gold-lidded container topped with a whale in the round, which became the inspiration for the Vancouver Aquarium’s Skaana—Killer Whale, Chief of the Undersea World, 1984.

In 1971 Reid wrested himself away from his workbench long enough to produce a written work. In the late 1960s, photographer Adelaide de Menil and anthropologist Edmund “Ted” Carpenter had approached Reid about contributing to a publication of photographs of decaying totem poles still standing in their original locations on Haida Gwaii. Initially lukewarm to the idea, but now under financial duress, Reid came through with his contribution for Out of the Silence. In the text he expresses his appreciation for the cedar tree in an epic poetic outpouring of honour for the Haida people and lament for the people and their way of life.

Oh, the cedar tree!

If mankind in his infancy

Had prayed for the perfect substance

For all material and aesthetic needs

An indulgent god could have provided

Nothing better. Beautiful in itself,

With a magnificent flared base

Tapering suddenly to a tall, straight trunk

Wrapped in reddish brown bark,

Like a great coat of gentle fur,

Gracefully sweeping boughs,

Soft feathery fronds of gray green needles.

Huge, some of these cedars,

Five hundred years of slow growth,

Towering from their massive bases.

Reid’s poem had a powerful impact and stirred up feelings within him that contributed to his desire to return to the West Coast. He moved to Vancouver in 1972. With his network of connections established and expanding, Reid had several promising prospects to explore there. In tangible and intangible ways there was support for Reid in British Columbia.

Homeward Bound

Bill Reid’s return to the West Coast coincided with a significant personal reckoning. Having experienced spinal troubles for years, he was diagnosed in 1973 with Parkinson’s disease. The primary symptom, uncontrollable shaking, could be temporarily countered by exerting the affected muscles through applying pressure to tools. In this sense, the disease provoked Reid to work obsessively; in later years, as the illness progressed, his overall strength and technical ability were increasingly affected.

In the mid-1970s Reid met and later married Martine de Widerspach-Thor (née Mormanne), a French student at the École des hautes études en sciences sociales in Paris who was pursuing a PhD in anthropology at the University of British Columbia. Martine was passionate about Reid’s work and supported his pursuits. “We didn’t need to talk much,” she remembers, adding, “I was in love with his mind.” She became a repository of knowledge on Reid’s work and continues to support his legacy today.

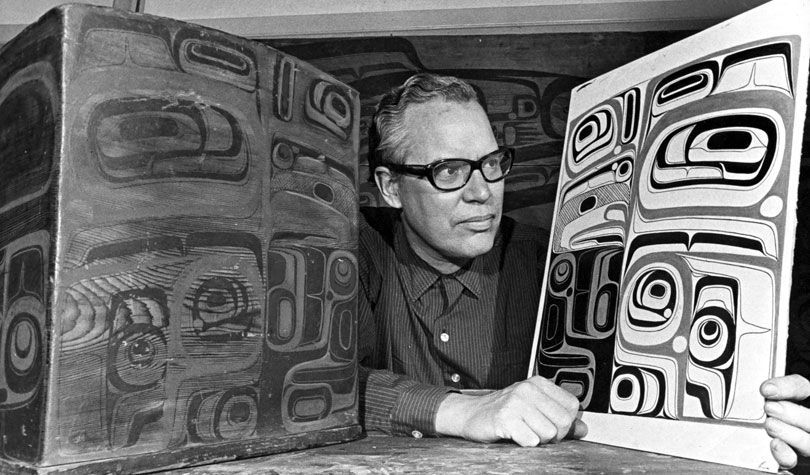

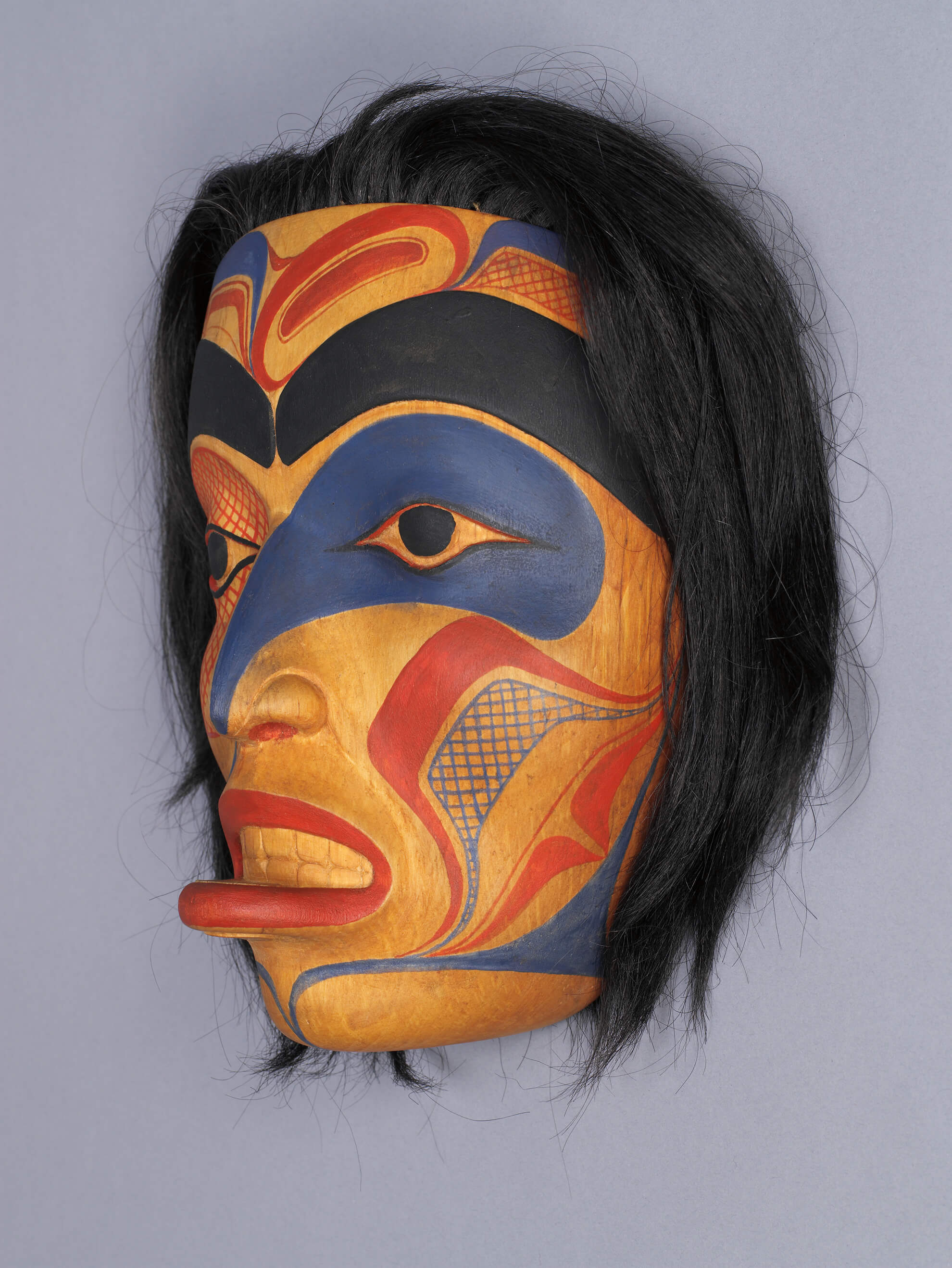

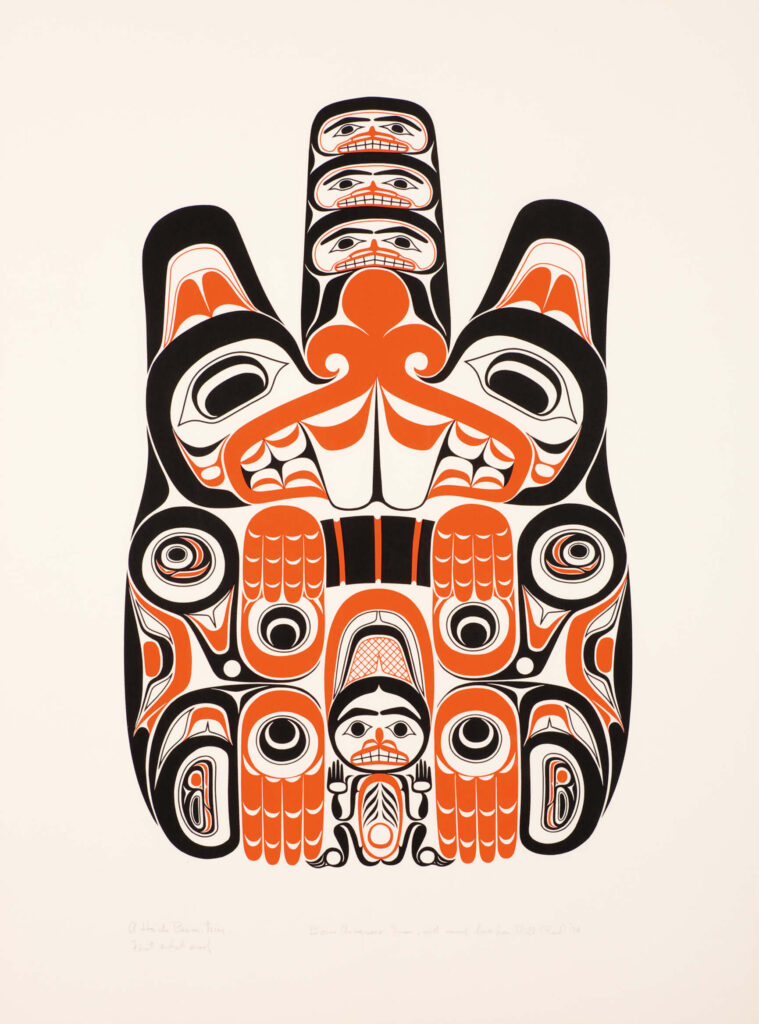

During this period, Reid’s self-expression benefited from paper-based images of his sculpture and jewellery designs that reached wider audiences as limited-edition prints and in published books. The 1970s brought in the prolific use of serigraphy, or screen printing, a technique that allowed artists to reproduce graphic designs in limited-edition prints; Reid’s 1979 Haida Beaver – Tsing serigraph is one example. Serigraphs reproduced Haida art well because the medium accommodated the graphic qualities of formline work—the language and rules of which had been researched and articulated by artist and art historian Bill Holm (b.1925) in the 1960s. Reid knew Holm’s work—at the invitation of Ted Carpenter, he collaborated with him on a text for Form and Freedom: A Dialogue on Northwest Coast Indian Art (1975), the catalogue for an exhibition presented at Rice University in Houston, Texas. The text records a conversation between Reid and Holm in which they informally discuss the form, technique, mythic context, and cultural history of many objects in the exhibition—including masks, pipes, and bentwood boxes.

Community and Political Activism

As Bill Reid’s reputation as a significant Canadian artist developed, he engaged with the political and community activism of the Haida Nation, with a particular interest in Skidegate, his mother’s community. In the early 1970s a conversation between Chief Councillor Percy Williams and Reid gave rise to a common lament: a little over a century earlier, Haida Gwaii had been home to hundreds of totem poles that portrayed the lineages of the great Haida families, yet none now stood in Skidegate as a consequence of the Indian Act and potlatch ban. To Reid it seemed “ridiculous that there shouldn’t be at least one [pole] to stand guarding the fates and destinies of the people of Skidegate.” So in 1976 Reid decided to “indulge a lifelong dream” by living among the people of Skidegate for more than just a few days and carving a pole in honour of his mother’s childhood home and her community.

Reid’s creation of the Skidegate Dogfish Pole, 1978, marks a period of cultural significance for both Reid and Skidegate. While the community provided lodging and food on occasion, Reid personally funded the project and viewed the pole as a potlatch gift. He described it as his way of giving back to the community: “It is a gesture of thanks on my part to all the great carvers, and all the people who supported them in the past. For the last eight thousand years, at least, people have been carrying on the art of the Haidas on these islands. And it is that heritage that I drew on to do whatever little things that I have been able, to perpetuate this great art form.”

Reid designed and carved the pole with the assistance of Guujaaw (b.1953), Robert Davidson, Gerry Marks (1949–2020), and Joe David (b.1946) over the summers of 1976 and 1977. The people who lived in Skidegate did not initially take an active interest in Reid’s pole as it was being carved. However, as the day of its raising approached, Elders were consulted, and a two-day potlatch was organized. One thousand five hundred Native and non-Native guests honoured the occasion, and for the first time in a generation the people of Skidegate came together to sing, dance, and potlatch openly.

With the raising of the Skidegate Dogfish Pole, Reid’s Haida name Iljuwas (Princely One or Manly One), which had been given to him in 1954, was publicly confirmed. He was continuing his work as an artist and activist in support of the Haida people and their culture, leaving a significant impact on the vitality of the Haida nation. Reid noted, “A culture will be remembered for its warriors, artists, heroes and heroines of all callings, but in order to survive it needs survivors.”

Monumental Sculptures

From the 1970s and into the 1990s, Bill Reid and his assistants produced major sculptural commissions. This was a period when Reid’s health became increasingly frustrating and perhaps even heartbreaking for him. He had to enrol and rely on many others to see his visions through to the end. But possibly, in a mysterious way what weakened him physically may have strengthened the impact of his artistic legacy. As he came to see with time, and especially with the carving and launching that brought to life his late masterwork Loo Taas in 1986, artmaking in Haida society depends upon community participation. That Reid could not do the work alone resulted in a kind of artistic potlatching—a gifting that afforded many the opportunity to be involved, to learn, and to remember.

Reid arrived in Vancouver from Montreal in 1972 after receiving a commission offer from Walter C. Koerner. The lumber magnate was captivated by Reid’s 1970 boxwood miniature, The Raven Discovering Mankind in a Clamshell, and proposed to fund the making of its monumental version, The Raven and the First Men, for the University of British Columbia Museum of Anthropology. Throughout the complicated process, Reid called in help from young Haida carvers, including Reg Davidson (b.1954), younger brother of Robert Davidson, and Jim Hart (7idansuu, b.1952). Non-Native assistants George Norris (1928–2013) and George Rammell (b.1952) also took an important part in the project. The sculpture took seven years to carve and was completed in 1980. Reid also worked with Arthur Erickson (1924–2009), the architect designing the Museum of Anthropology; Erickson’s placement of the work created an iconic cultural destination.

In 1984 two other monumental sculptures evolved from earlier works. Themes and forms explored in Cedar Screen, 1968, and Panel Pipe, 1969, found their large-scale interpretation in Mythic Messengers, 1984, a cast bronze commission mounted on Teleglobe Canada’s building in Burnaby, B.C. Killer Whale, 1982, grew into its monumental version, Skaana—Killer Whale, Chief of the Undersea World, 1984, and was installed outside the Vancouver Aquarium. Although these were large works, Reid insisted they be finished with the precise attention of a goldsmith. In alignment with Haida views, he understood that his craftsmanship was not for human eyes alone—that, regardless of scale, care in producing a well-made object took into account that the “gods see everywhere.”

Reid also contributed to books during this period. For instance, he created illustrations for George F. MacDonald’s 1983 publication Haida Monumental Art. He also came to know Canadian linguist and poet Robert Bringhurst (b.1946), a scholar of Haida oral culture. Reid and Bringhurst collaborated on The Raven Steals the Light, published in 1984. Reid provided illustrations for the book and tried his hand at writing stories, among them “The Bear Mother and Her Husband” and “The Raven and the First Men.” These were stories Reid had first heard from Henry Young during his visit to Skidegate at age twenty-three. In commenting on the project, Reid adamantly expressed that his retelling of the stories was interpretative and that he “took the bones from those sources then fleshed them out to make them more lively.”

In 1985 Reid was commissioned to produce a work for the Canadian Embassy in Washington, D.C., a building being designed by Erickson. The resulting monumental sculpture was Spirit of Haida Gwaii: The Black Canoe, 1991. In this work a vessel overflows with a delegation of human and mythical characters floating far beyond the waters of Haida Gwaii. Spirit of Haida Gwaii initially became famous because in 1987 Reid temporarily ceased working on it to draw attention to the Haida Nation’s plea for the protection of Athlii Gwaii (Lyell Island) forests. In 1996 a second casting of this artwork was produced, this time with a green patina. Named Spirit of Haida Gwaii: The Jade Canoe, this iteration was installed in the Vancouver Airport in 1996. These twin sculptures came to be Reid’s best known and most publicly accessible works.

Concurrently, another notable community project was taking shape. The creation of the monumental canoe Loo Taas was completed in Skidegate, just in time to grace the waters at Expo 86 in Vancouver. Loo Taas is significant not only for Reid but for the Haida Nation. Every step of making Loo Taas connected the people to their ancestors. The process summoned the community to remember and enact in the present Haida knowledge and ways of being. She embodied a living entity of Haida culture, one critical to the ongoing functioning and health of Haida society.

In the last years of his life, Reid’s monumental sculptures succeeded in harnessing Haida ways of seeing. They captured the imagination of audiences in the contact zone, a contemporary entanglement of people from many nations inhabiting Turtle Island, otherwise known as North America.

Reid Remembered

In my heart, I believe that in the end, Bill had got there. Bill—Iljuwas—is a Haida. Bill—Iljuwas—is a Haida with many names. Bill—Iljuwas—was born and was given the supernatural gift that we all respect. There isn’t anyone anywhere who can take that away from him, because nobody on this earth can take away what the supernaturals give.

Bill Reid died on March 13, 1998, after living with the pain and discomfort of Parkinson’s disease for over twenty-five years. His memorial service unfolded in three parts, testifying to the profound impact of his life and career. First, on March 24 a six-and-a-half-hour ceremony, attended by more than one thousand Indigenous and non-Indigenous guests from every facet of Reid’s life and Canadian society, was held in the Great Hall at the University of British Columbia Museum of Anthropology in Vancouver. A second service along with a feast was held in Skidegate on Friday, July 3, followed by the burial of Reid’s ashes at T’aanuu, the ancestral village of his grandmother, on July 5.

Throughout the proceedings, Reid’s remains were carried in custom-made boxes commissioned by Martine J. Reid. Richard Sumner, Kwakwaka’wakw master carver and painter, made a red cedar bent corner box to hold the ashes—an exact replica of the nineteenth-century bentwood box Reid had admired all his creative life and labelled “the Final Exam after the Master of the Black Field.” This was housed inside a larger box carved by Haida sculptor Don Yeomans (b.1958). From Skidegate to T’aanuu, these were transported in Loo Taas, the grand canoe that in many ways embodied Reid’s greatest achievement.

I was witness to his memorial at the University of British Columbia Museum of Anthropology. Speeches were given all through the late afternoon and into the evening. I sat behind the podium, unable to move for the entire time, except to present my speech. It seemed as if an ancient protocol demanded of us our most acute attention. Where Reid once created works by rebuilding a small village of houses and poles, still standing outside the museum to honour his heritage, the museum and everyone who attended the memorial came to honour him. In keeping with the aesthetic principles of Haida art, coexistence and relationality, the museum that day transformed into something far more powerful than a building full of visitors coming to see the art.

During the memorial, over sixty individuals spoke—a deeply stirring tribute to the fully dimensional human being that was Bill Reid. George Rammell, having worked on fifteen of Reid’s projects over eleven years, recalled the broad range of roles attributed to Reid, saying, “Bill was called a trickster, a wizard, a cultural saviour, a mentor, a liberal, a plaintiff, a defendant, a critic, an activist, a modernist, a maestro, an honorary doctor, a shaman, a wolf, and a Haida.” Don Yeomans declared, “He was the vanguard; he was the example of contemporary mastery; he understood design and was proficient in every medium and on every scale; he was the paradigm of my generation.”

Closing the event with a view to the future, Chee Xial (Miles Richardson Sr.), the hereditary chief of Reid’s Raven-Wolf Clan and the master of ceremonies, said: “A forest doesn’t die when the old trees die. A forest dies when the young trees die. And Bill has given all of us, Haida . . . everyone . . . so much insight, so much wisdom through his doing, and so much strength through his example.” Chee Xial recognized that, through the arts, Bill Reid had gifted Canadians with tools of reconciliation. Honouring Reid’s legacy, he urged, would require that the next generations employ these tools.

My connection to Bill Reid ended as it began: with a sense of reverence. If the memorial was any indication, indeed, many others felt the same way. Hundreds of people attended the memorial at the place where his career had begun. Though it could have begun in Haida Gwaii, Reid’s career has been tied to the museum: from its inception, to the commissioning of The Raven and the First Men, 1980, to his eventual memorial—his career has been linked to the Museum of Anthropology. While local photographers such as Rodney Graham (b.1949), Jeff Wall (b.1946), and Stan Douglas (b.1960) have put Vancouver on the international art map as the Vancouver School, visitors to British Columbia inevitably come to see Northwest Coast Indigenous art, whether at the University of British Columbia Museum of Anthropology or at regional museums. Many continue venturing, as they have in the past, to visit a number of Indigenous communities up and down the coast. Reid is partially responsible for this allure. Visitors stepping off the plane immediately come into contact with the art of the region, including Reid’s emerald-coloured Spirit of Haida Gwaii: The Jade Canoe, 1996.

The simultaneity of transformation that scholars speak about in Northwest Coast art happened at the memorial, if only between Reid and the museum, man and institution. While debates about his identity continue, we can be certain that Reid’s contribution to Canadian art is unquestionable.

In a chorus of many, Reid was sent off with songs and drumming, laughter and tears—many voices concluding with the words Thank you Bill, Haawa Iljuwas, Haawa Yalth-Sgwansang.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements