Alberta-born artist William Kurelek (1927–1977) often explored his Ukrainian heritage and the cultural diversity of our nation in his widely popular paintings. While Kurelek was initially focused on portraying the Ukrainian-Canadian immigrant experience, the growing multicultural nationalism of the 1960s inspired him to paint several series dedicated to other major ethnic and cultural groups in Canada in the 1970s.

Kurelek developed what he later described as his “ethnic consciousness” during public school in rural Manitoba, around the same time his artistic identity began to emerge. His artistic confidence and ardour for his parents’ heritage was further nurtured by cultural classes he attended as an adolescent and reinforced at university through his involvement in the University of Manitoba’s Ukrainian students’ club and his friendship with Zenon Pohorecky, a fellow student (and future anthropologist of Ukrainian culture) whose art revealed a deep interest in the “interplay between creative pursuit and ethnic identity.”

Oil on Masonite, 121.9 x 152.6 cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Although matters of social consciousness and the recovery from mental illness became Kurelek’s central artistic concerns during the 1950s, themes of ethnicity and cultural identity appear throughout many of his early works, from Zaporozhian Cossacks, 1952, to The Maze, 1953. His representation of Ukrainian culture became more prevalent in the early 1960s, especially with his 1964 series An Immigrant Farms in Canada, featuring such works as Manitoba Party. However, the series was less a celebration of ethnic identity and more an attempt to honour and repair his relationship with his parents, particularly his father.

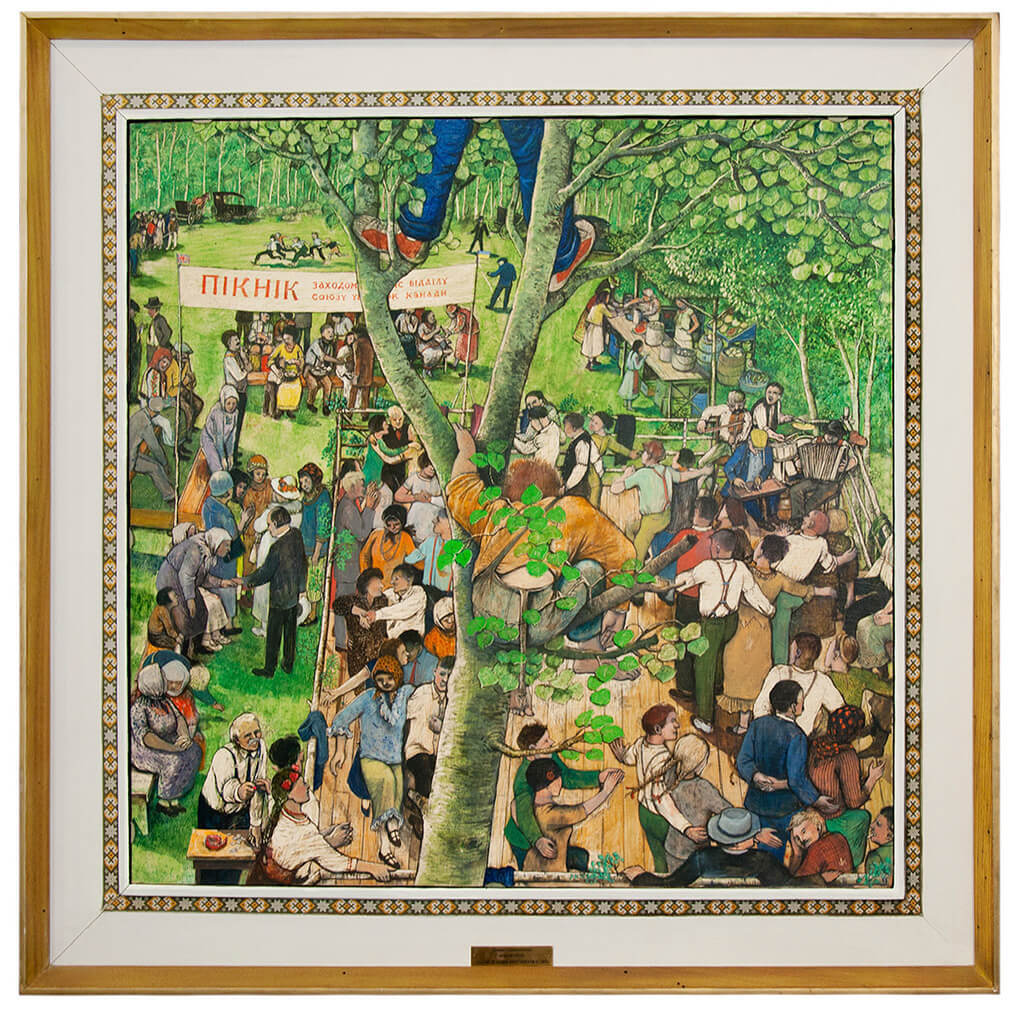

With the approach of the Canadian Centennial in 1967 and the emergence of a multicultural nationalism, Kurelek began to push the discussion of his Ukrainian heritage into one about the history of Canadian nationhood. Between 1965 and 1967 he completed a series about the roles of Ukrainian women in Canada. The timing and public function of it were significant: not only did it serve to mark the fortieth anniversary of the Ukrainian Women’s Association of Canada and the seventy-fifth anniversary of Ukrainian immigration to Canada, but the Ukrainian Pioneer Woman in Canada series, composed of twenty works, including Ukrainian Canadian Farm Picnic, 1966, displayed at the Ukrainian Pavilion at Expo 67 in Montreal, was presented as a Canadian national signifier. In 1983 the federal government acquired and installed the monumental, multi-panelled The Ukrainian Pioneer, 1971, 1976, on Parliament Hill, where it remained until it was transferred to the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, in 1990.

Oil on panel, 70.5 x 70.5 cm

Ukrainian Museum of Canada of the Ukrainian Women’s Association of Canada, Saskatoon

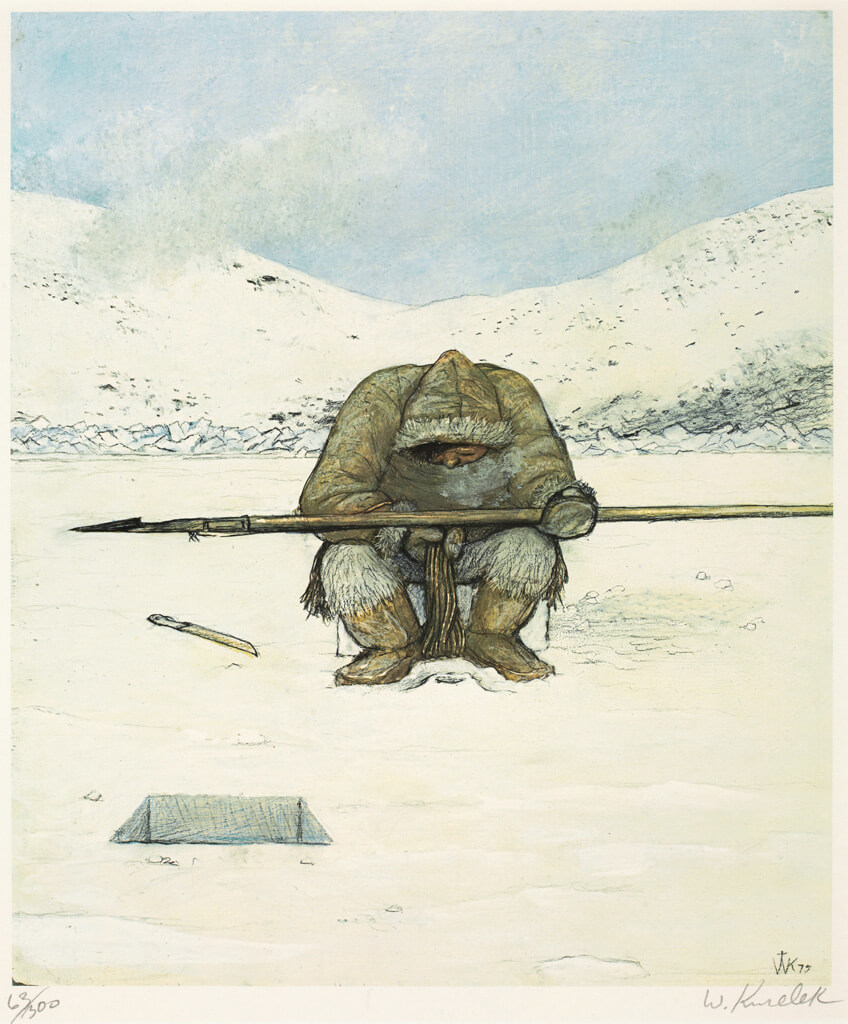

By the early 1970s Kurelek could confidently proclaim that the “days of Anglo-Saxon domination are gone.” He expanded his repertoire in the 1970s to include optimistic expressions of the postwar era’s multiculturalism. He crisscrossed the country on a quest to capture the cultural diversity of the country’s inhabitants and produced series and publications honouring Canadian Jewish, Polish, Irish, Francophone, and Inuit peoples. When he died suddenly in 1977, Kurelek had been planning two series, about German- and Chinese-Canadians, respectively.

Mixed media on board, 50.8 x 57.2 cm

UJA Federation of Greater Toronto

Kurelek’s representations of non-European and Indigenous peoples are not unproblematic. The title of his 1976 book, The Last of the Arctic, for instance, betrays a common misconception, namely that Inuit culture was a static set of beliefs and customs that were disappearing because of infiltrating southern institutions and technologies. Such views were not unique to Kurelek. Christopher Ondaatje, owner of the book’s publishing house, Pagurian Press, had commissioned Kurelek to present a nostalgic view of Arctic life, “to paint it before it had its streetlights and Skidoos and telephone poles.” Such outdated representations have since been superseded by the work of renowned Inuit artists, including Annie Pootoogook, Shuvinai Ashoona, and Oviloo Tunnillie, who explore contemporary life in the Arctic from an insider’s perspective.

Photographic lithograph, 47.9 x 40.6 cm

The Robert McLaughlin Gallery, Oshawa

This Essay is excerpted from William Kurelek: Life & Work by Andrew Kear.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

Defiant Spirit

Quebecois artist Ozias Leduc drew on Europe but created a Canadian ideal

By Laurier Lacroix

Defiant Spirit

Quebecois artist Ozias Leduc drew on Europe but created a Canadian ideal

By Laurier Lacroix