Zaporozhian Cossacks 1952

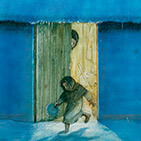

William Kurelek, Zaporozhian Cossacks, 1952

Oil on Masonite, 102 x 152 cm

Winnipeg Art Gallery

This is Kurelek’s earliest attempt to articulate the deep ambivalence he felt toward his father, Dmytro. A heroic but terrifying tribute, the painting symbolically represents Dmytro as a Cossack leader capable of arbitrating the ultimate judgment that will determine the fates of those around him.

Created upon Kurelek’s return to Canada from Mexico, this painting was influenced by mural painting by artists such as Diego Rivera (1886–1957), José Orozco (1883–1949), and David Siqueiros (1896–1974). The work’s subject matter also drew inspiration from two sources that reflected the artist’s lineage to the Cossacks, warrior-traders who emerged in the late 1400s and settled in the grasslands of what is today southern Ukraine. To date they are “one of the main symbols of Ukrainian historical identity.”

The painting pays homage to Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks, 1880–91, by Russian artist Ilya Repin (1844–1930). Kurelek had saved a black and white image of the painting in a scrapbook, and his own painting exaggerates the animated expressions of the figures in Repin’s original. The work’s second major reference is Taras Bulba (1835) by Russian-Ukrainian author Nikolai Gogol. The historical epic tells the story of the eponymous Ukrainian patriarch and his relationship with his two sons: the adventurous favourite, Ostap, and the romantic introvert, Andriy. Taras Bulba eventually kills Andriy when he discovers that the latter was prompted by a woman’s love to aid the Polish enemy.

Gogol’s novel has been interpreted as a celebration of Ukrainian nationalism. It also places a premium on chauvinism, physical prowess, and male bonding, values Kurelek associated with his father and that filled him with a sense of inadequacy as a child. One of the Cossacks thronging around the Hetman in Kurelek’s painting bears some resemblance to the youthful Kurelek.

Painted over four weeks in December 1951, soon after Kurelek had returned from working in the lumber camps in Northern Ontario and Quebec to live at his parents’ farm in Vinemount, Ontario, Zaporozhian Cossacks was presented by Kurelek to his father as a parting gift before the artist left for Europe.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements