Zacharie Vincent adapted genres, materials, and media as he needed them. For his self-portraits, there is some evidence that he often traced facial features from photographs of himself. He carried out complicated experiments with different materials, sometimes to the detriment of the durability of his own productions, particularly the works on paper.

Speaking in Images

In 1879 the journalist and historian André-Napoléon Montpetit reported, in an article, a revealing fact: Vincent suffered from a speech impediment. He stammered, an unusual handicap in a leader. This dysfunction could partially explain his attraction to a pictorial medium. Suffering from this difficulty in speaking while being the focus of constant observation as chief, Vincent may have spontaneously adopted a language of pictures to express his ideas, his social condition, and that of his community. This transfer of communication from an oral to a visual form would not have been unfamiliar to his community: the missionaries had often used images in their campaign to convert Native peoples, and images had also proved to be effective tools for the transmission and exchange of information.

Influences

Art historians assert, without offering any documentary proof, that the portrait of Vincent painted by Antoine Plamondon (1804–1895) was the catalyst for his subsequent artistic career, and that he took lessons from respected artists of the time. However, the Plamondon portrait and Vincent’s first self-portraits are separated by an interval of fifteen years—though he may have produced other work that has been lost or remains unattributed. In the 1980s Marie-Dominic Labelle and Sylvie Thivierge, two of the authors of the entry on Vincent in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography, took up this theme again, hypothesizing that Vincent was the artistic heir of Plamondon. But they concede that “opinion is so divided on the matter of Vincent’s visual education that it is a practical impossibility to speak with any certainty on the subject. However, it is our belief that (at the very least) professional contacts existed between Plamondon and his model, and that these contacts could certainly have led to conversations that included artistic advice.”

The art historian Mario Béland is likewise circumspect, finding only that a correlation exists between Plamondon’s work and Vincent’s artistic enterprise: “Plamondon’s canvas was undoubtedly a major factor influencing Vincent’s choice of an artistic career.” His colleague Pierre Landry also asserts that Vincent benefited from the advice of Henry Daniel Thielcke (c. 1788–1874), Antoine Plamondon, and Cornelius Krieghoff (1815–1872). These hypotheses rest on the stylistic, thematic, and compositional parallels between Vincent’s work and that of his contemporaries. Paintings by these artists, which followed the current tastes of the British, French, or Italian academy, certainly had some impact on Vincent, but he retained from their pictorial language only their power to represent, to evoke, and to reproduce. With his self-portraits Vincent seems to declare himself the equal of colonial artists of the time, despite his lack of formal training, by reproducing some of their academic methods; the photographs showing him at work appear to confirm this.

Technical Experimentation

Vincent experimented with media as different as oil paint, graphite, charcoal, ink, and watercolour. Some witnesses claim that he created religious works for the church of Notre-Dame de la Jeune-Lorette and that he also sculpted in wood. He used a wide range of materials: canvas, paper, paper mounted on cardboard, cardboard, and wood fibreboard panels. He is also said to have used plant-based pigments or dyes to colour his artisanal products.

Vincent in all probability used whatever materials he could afford and whatever was available, and yet he still showed remarkably bold techniques. The precariousness of his position and the difficulty of obtaining good-quality materials may also explain why his application of oil pigments varies from one picture to another, from a heavy impasto to a more graphic style, in which traces of the underlying drawing in charcoal can be seen through the thin layer of paint.

He tried various methods of reproducing certain details more rapidly: stencils, tracing paper, and even painting on photographs. Vincent’s self-portraits are said to have been created with the aid of a mirror or from studio photographs, such as those taken by Louis-Prudent Vallée (1837–1905).

The Role of Photography

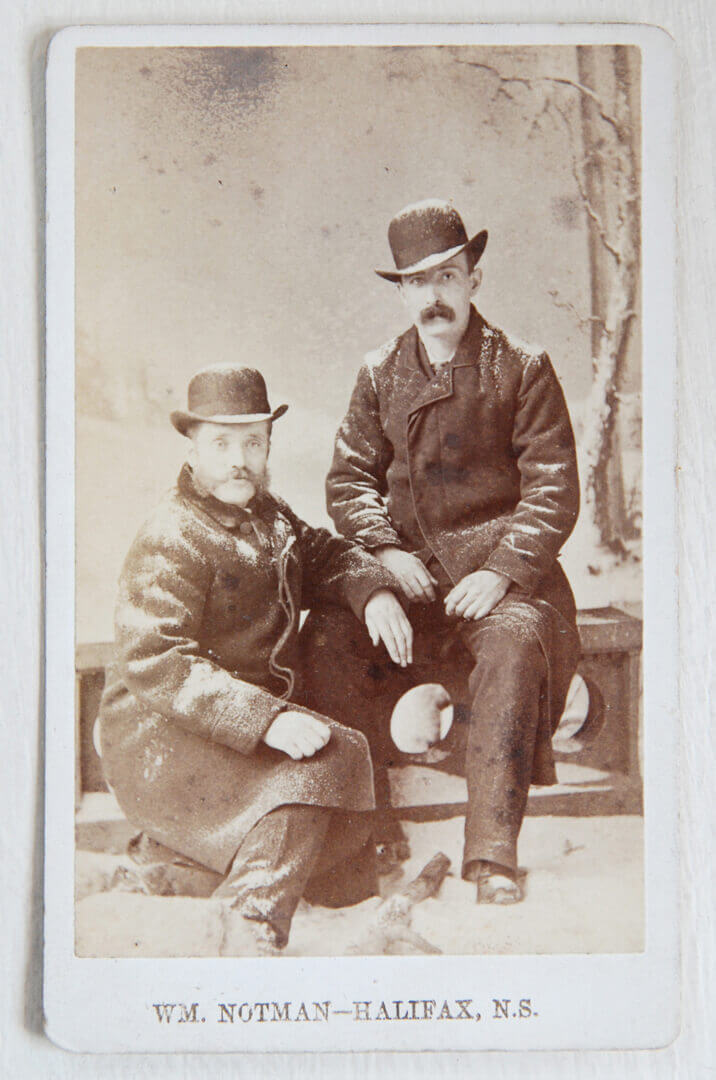

During the 1860s and 1870s the photography studios of Livernois and Vallée in Quebec City and William Notman (1826–1891) in Montreal, Halifax, and Toronto were becoming increasingly popular. Photographic images were essentially documentary in nature, so the medium was not in direct competition with painting, and it provided artists with some useful tools, both technical and commercial.

Painters often made use of photographs as visual sources for portraits and landscapes. For his painting Lorette Falls, c. 1860, for example, Vincent presumably drew inspiration from a photograph or a print based on a photograph of this picturesque site. Engravers used photographs as models to create images for illustrated newspapers, magazines, and books. Similar pictorial designs were even reproduced on serving platters and other earthenware.

The ease with which photography-based images could be created and distributed offered clear commercial advantages. Many artists used photography as a tool to promote their professional interests. Cartes-de-visite (calling cards) adorned with photographic images were a popular craze in the 1870s.

Vincent undoubtedly sought to benefit from the medium of photography, both to reach a wide audience and to enhance his artistic image to maximum effect. He also made use of photography for his own artistic purposes. He used the Louis-Prudent Vallée studio portraits to authenticate his personal claim to the status of artist, offering evidence to the public that he was in truth the creator of his own self-portraits. This use is most clearly seen in Vincent’s Huron Chief Zacharie Vincent Telariolin Painting a Self-Portrait, c. 1875.

Over the stereotype of the Native as a passive victim, fated to disappear, Vincent superimposed another image—that of an active, creative, and highly individual personality. The self-portraits allowed the artist to portray his subjective reality, creating a lasting image that would endure through time and space; they reclaimed the authority of the Native subject to define his own community as he saw it, and they opened a dialogue with the public. Photography completed this process of affirmation by recording the objective, concrete reality of Vincent’s life.

Authentication of the Works

The works that have survived are not in good condition; they have been either stored in unsafe environments or made with poor-quality or fragile materials, or else the artist used vegetable dyes that have deteriorated.

Vincent’s works are not signed, and the artist left no written record or other evidence that sheds light on his creative process. The absence of any signature or identifying labels on his works would have presented problems of attribution at the time; a further complication was the fact that other artists had painted portraits of Vincent and his eldest son, and that these paintings were also in circulation. Later, to dispel any doubts the public might have, and to increase the market value of his self-portraits, Vincent often included an inscription with his self-portraits and went so far as to have photographs taken showing him at work on the paintings, to prove that he was indeed their creator.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements