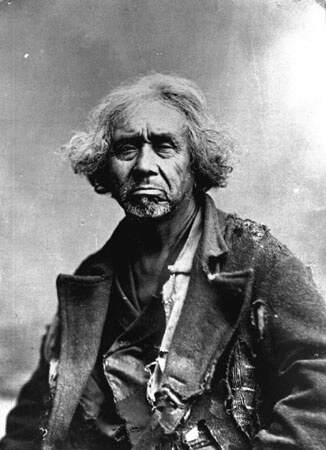

Zacharie Vincent Telari-o-lin, Huron Chief and Painter c. 1875–78

Zacharie Vincent, Zacharie Vincent Telari-o-lin, Huron Chief and Painter, c. 1875–78

Oil and graphite on paper, 92.7 x 70.8 cm

Château Ramezay, Montreal

Based on the detailed rendering of the facial features, the shadows, and the volume of the hair, this self-portrait appears to have been painted from a photograph by Louis-Prudent Vallée (1837–1905), a half-length studio portrait that was also likely used by Vincent to model Huron Chief Zacharie Vincent Telariolin Painting a Self-Portrait, c. 1875. Vincent takes care to authenticate his work by including an inscription, in French and English: “ZACHARIE VINCENT TELARI-O-LIN CHEF HURON ET PEINTRE / Son Portrait Peint Par lui Même / ZACHARIE VINCENT TELARI-O-LIN INDIAN HURON CHIEF HIS PORTRAIT PAINTED / By Himself.” The bilingual title suggests that this work was intended for the tourist market.

In this tightly framed half-length self-portrait, Vincent looks directly at the viewer. He holds a pipe tomahawk in his right hand and a staff in his left. In contrast to the powerful modelling of the facial features, the hands are simply executed. The wampum belt across his chest and the red and blue arrow sash around his waist are noticeably flattened, without shadows or modelling. Vincent captures the bulk of the shirt, but the folds in the cloth are not painted realistically.

The forested background, unique among Vincent’s self-portraits, is dominated by sunlit hills under a bright blue sky—a panorama quite unlike the darkly shadowed horizon in Portrait of Zacharie Vincent, Last of the Hurons, 1838, by Antoine Plamondon (1804–1895). The fusion of portrait and landscape is part of the Romantic tradition, a new dialogue with nature that European civilization had opened: in the protoindustrial context of the time, both nature and the Native subject were considered under threat of extinction.

The parallel that Vincent draws here between the flamboyant chief and the radiant hills was no doubt intended to strike a blow against the defeatist tales being told of his people’s decline. As for the motif of the figure in the landscape, that too can be taken two ways: to the colonial population of Lower Canada it might represent the conquest of the wilderness, while to Native eyes the wilderness would represent a reminder of their claims and a freedom that needed defending.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements