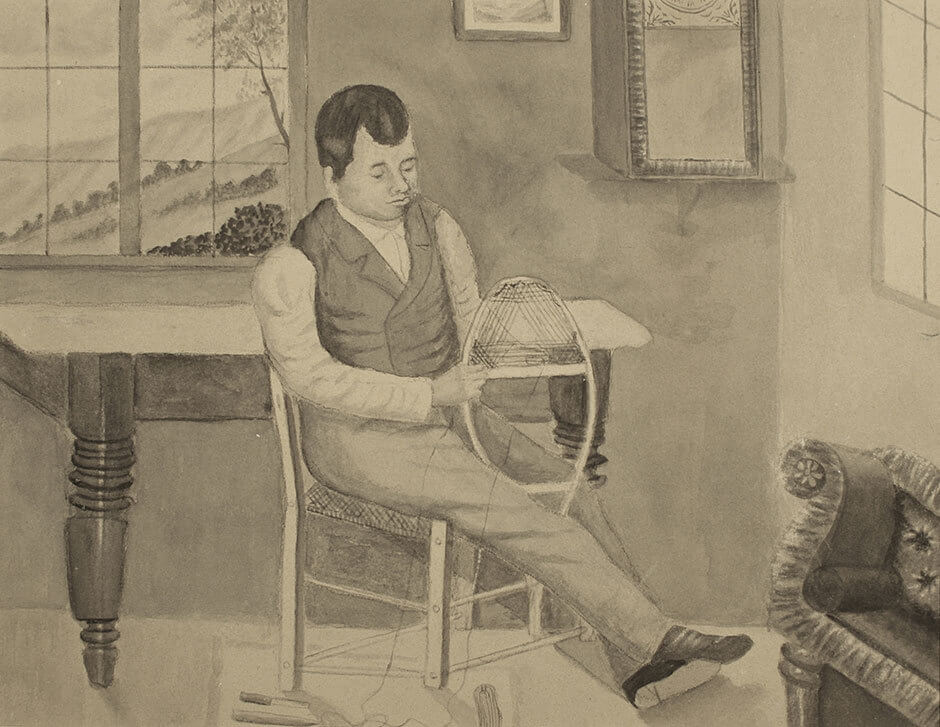

Snowshoe Maker n.d.

Zacharie Vincent, Snowshoe Maker, n.d.

Graphite and wash on paper, 23 x 30 cm

Château Ramezay, Montreal

Vincent’s Snowshoe Maker shows an artisan at work. Seated in a cane chair, the man weaves the head of a snowshoe. A roll of hide strips, an awl, and a knife are at his feet. Images like this, of Native craftsmen in a domestic setting, were a powerful counter-argument to the assumption that Native people lived exclusively in nature.

These images also capture scenes that photography at the time was unable to record: except in professional studios, interior lighting was usually inadequate. Photographers were often obliged to move their subjects outdoors. Vincent’s work, by bearing witness to the actual conditions of working people, becomes part of an important documentary tradition.

Snowshoe Maker is part of a series in which Vincent illustrates the various stages in the manufacture of snowshoes. This occupation had been practised for centuries by the nomadic and semi-nomadic peoples of the North, who lived in territories criss-crossed by a vast network of lakes and waterways. The snowshoe became a symbolic object, representing not only the deep territorial roots of Native culture but also the adoption of Native customs by the European colonists.

Throughout the nineteenth century snowshoes were an indispensable part of the equipment of soldiers, prospectors, surveyors, and railway builders. After 1840 they experienced a burst of new popularity thanks to the appearance of snowshoers’ clubs. Native snowshoe makers did their best to keep up with the rising demand, but what had been a small artisanal trade practised by individual craftsmen who made and sold their own goods now developed into an industry, with specialization of tasks. The artisans of Jeune-Lorette had a large share of this market. Adapting traditional methods to the new realities, they began to work with new, more sophisticated tools, in the comfort of their own homes.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements