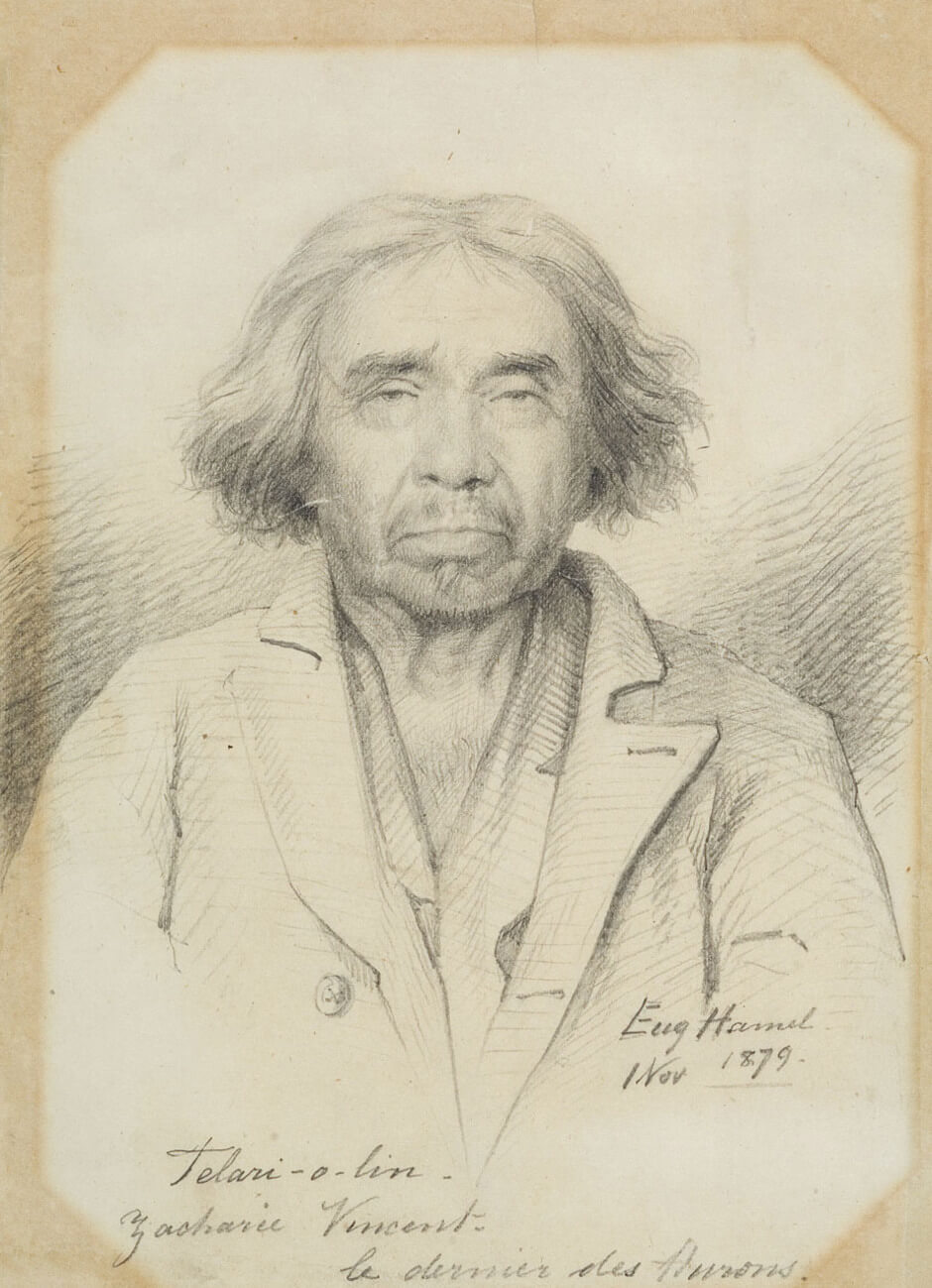

Zacharie Vincent was born on January 28, 1815, in the Huron-Wendat village of Jeune-Lorette, about fifteen kilometres north of Quebec City in what is now the Wendake Reserve. His practice as an artist—particularly through his self-portraits—enabled him to overturn conventional ideas about Native-colonial relations, establish a dialogue between the two communities, and create a vital, actualized image of his own reality. He died in 1886 in the Marine and Emigrant Hospital in Quebec City.

The Huron-Wendat Heritage

The Huron-Wendat people originally occupied territories near the Great Lakes, but toward the end of the seventeenth century they migrated to Quebec under the protection of Jesuit missionaries. Zacharie Vincent was the son of Chief Gabriel Vincent, a fervent traditionalist and defender of Huron-Wendat culture, and Marie Otis. He was the nephew of Grand Chief Nicolas Vincent and the uncle of Prosper Vincent, the first Huron to be ordained a priest. Zacharie Vincent was known in the nineteenth century as “the last pure-blooded Huron.”

Education

It is not known whether Vincent received any formal education, but it is possible that he did not, given that few Native children attended school before 1830. Nineteenth-century commentators describe Vincent as gifted, with a natural talent; from his early childhood he showed a facility for drawing and painting, from life or secondary sources. They agree that he had been tutored or advised by various well-known artists. A study of his landscapes, genre scenes, and portraits confirms that Vincent likely drew inspiration from the works of William Henry Bartlett (1809–1854), Cornelius Krieghoff (1815–1872), Henry Daniel Thielcke (c. 1788–1874), Théophile Hamel (1817–1870), and Eugène Hamel (1845–1932), as he did from engravings in illustrated newspapers.

Huron Chief

When Vincent was thirty-three he married Marie Falardeau, a twenty-year-old Iroquois widow who had lost the two children from her first marriage. With Vincent she would go on to have four more children: Cyprien, Gabriel, Zacharie, and Marie. Only two survived into adulthood, Cyprien (1848–1895) and Marie (1854–1884), and neither left descendants.

Vincent was named war chief in 1845 and played an active part in the life of the Huron community. He devoted himself to painting, hunting, artisanal crafts (the manufacture of snowshoes in particular), and jewellery making. He also acted as a hunting guide for Quebec City residents, visitors, and soldiers from the British garrison.

“The Last of the Hurons”

Vincent’s decision to embark on an artistic career seems to have been inspired by a number of events, the most important of which was the painting of his portrait by Antoine Plamondon (1804–1895). Created in 1838, the painting shows Vincent as a young man and is titled Portrait of Zacharie Vincent, Last of the Hurons. The art historian François-Marc Gagnon explains that this work would have been seen at the time as allegorical. It was created in the immediate aftermath of the defeat of the nationalists in the Rebellion of Lower Canada in 1837, also known as the Patriots’ War. The portrait of “the last of the Hurons” was an indirect expression of anger at the fate of the French Canadians, whose society was also now threatened with dissolution and extinction. The Patriots saw themselves in their former Huron allies and held them up as models of cultural integrity.

Around this time the Huron nation was also experiencing serious political instability. The various measures the Hurons had undertaken since the eighteenth century to defend their territory had all ended in failure. The community was now looking to other strategies in their fight for survival: specifically, they were seeking to preserve their ethnic identity and revitalize their social and cultural life. As chief and “the last of the Hurons,” Zacharie Vincent was part of these efforts, both symbolically and actively, through his status as an example and role model and through the power of his artistic production.

The Huron Rebel

In 1838, while Plamondon was at work on his portrait of Zacharie Vincent, the artist Henry Daniel Thielcke completed a group portrait titled Presentation of a Newly Elected Chief of the Huron Tribe.

In this painting, the community has assembled to nominate Robert Symes as an honorary chief, in a symbolic ceremony of adoption reserved for the dignitaries of colonial society. Unlike his colleagues, who are dressed in the standard garb of officialdom and look directly at the viewer, Vincent (back row, to the left) wears an elaborate silver headdress decorated with feathers—a design he created—and looks to the side, showing his desire to express his individuality and to signal his position of cultural resistance.

An Artistic Dialogue

Vincent’s adoption of Western pictorial techniques such as perspective and drawing from photographs—particularly photographs of himself—allowed him to take back control of his own image and to offer a response to the depiction of Natives by artists such as Antoine Plamondon, Joseph Légaré (1795–1855), Cornelius Krieghoff, Henry Daniel Thielcke, and Théophile Hamel.

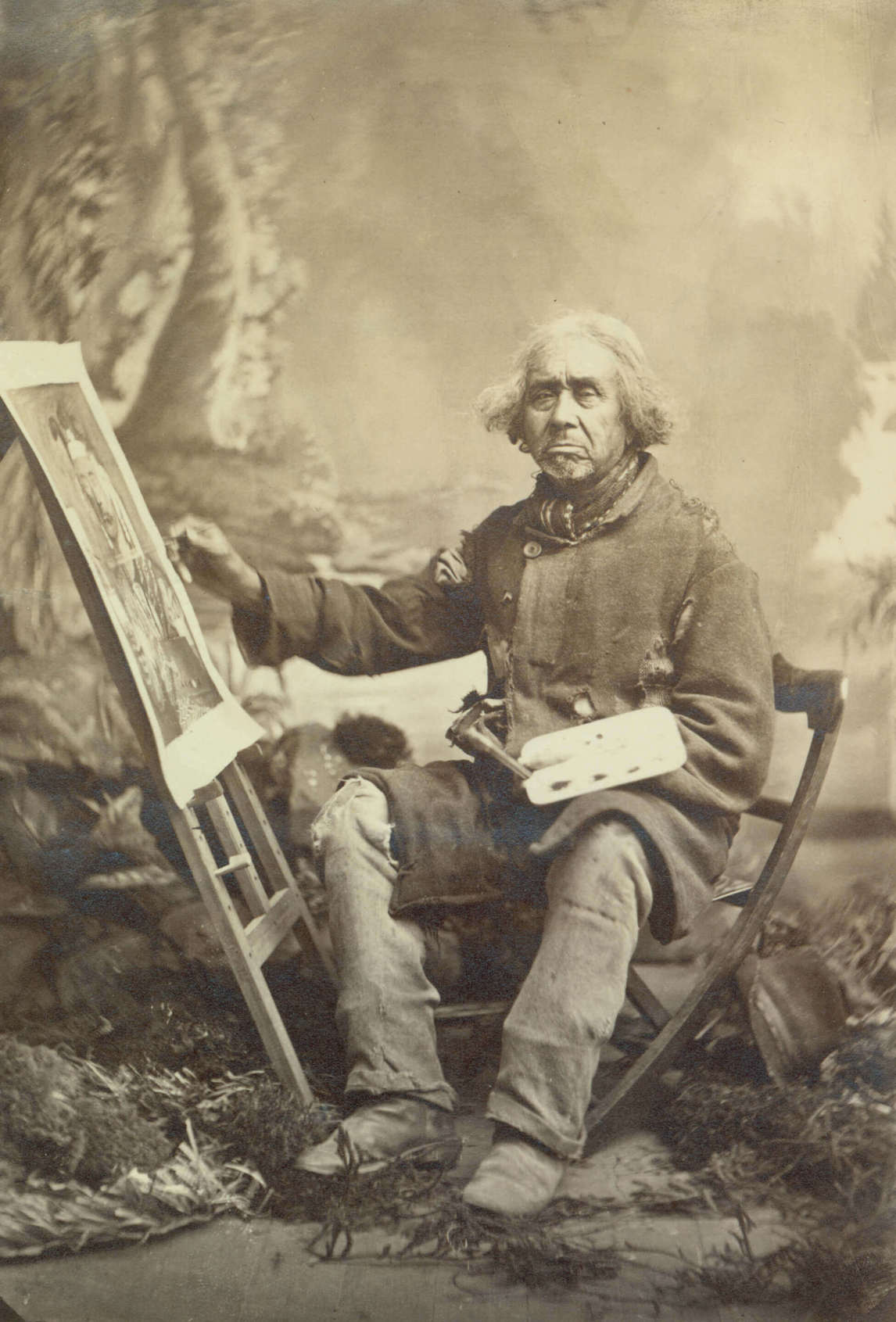

His body of work is estimated to include several hundred paintings and drawings. Vincent’s intention was always to combat the image of the Aboriginal subject as fixed in the past, exotic, nostalgic, and backward-looking, and to replace it with images of a complex identity influenced by the pressures of assimilation and encompassing the transformations brought about by cultural contact and alliances extending back two hundred years. He succeeded in creating a narrative both to counter alarmist predictions of the disappearance of the Native subject and to portray the reality of his community’s social and political life. By appropriating a Western pictorial medium and ensuring the wide distribution of his work, Vincent at the same time initiated a significant dialogue with the colonial population.

During his lifetime the artist sold paintings to tourists, soldiers in the garrison in Quebec City, and visiting dignitaries such as Lord Durham, Lord Elgin, Lord Monck, and Princess Louise. Several commercial establishments in Quebec that specialized in exotic items, postcards, and photographs would also have been outlets for his work. Vincent is one of those rare artists who have sold self-portraits in their own lifetime. This achievement may be attributed to the public’s enthusiasm for Native subjects and to the charisma he projected—as a chief, as “the last of the Hurons,” and as “the Huron artist,” a previously unknown category.

Over the years, he continued to adapt the tone of his work to boost its effectiveness with the audiences he wanted to reach. In this respect, the content of his art falls into three categories: cultural references that could be decoded only by members of the Huron community, typical or stereotypical elements that would be widely understood by the general public, and elements related to his own experience as an artist. By using well-known cultural references, Vincent attracted the interest of tourists and visitors, while at the same time conveying a subtle criticism of their complacent views and of the underlying dynamic of colonial power. These elements allow a richer and more complex reading of his work.

Later Years

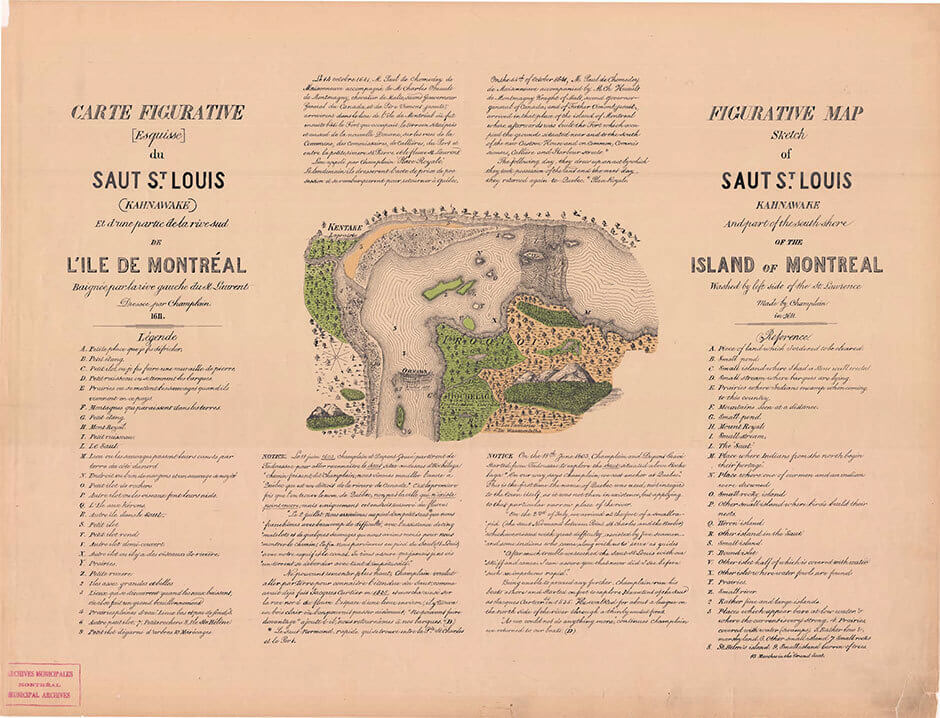

In 1879, at the age of sixty-four, Vincent either resigned or was removed as chief, and the position was taken over by his brother Philippe. He left the village of Jeune-Lorette and moved with his son Cyprien to Kahnawake, the Mohawk community, which was also associated with the Jesuits, on the river at Sault St. Louis, south of Montreal. This decision may have been prompted by the gradual encroachment on Huron hunting lands by colonial settlers and prospectors, the building of the railway, and the establishment of private hunting clubs.

Sault St. Louis was then the capital, or meeting place, of both the Iroquois League and the Federation of Seven Nations, an alliance that had been formed to unite the Christian First Nations of Lower Canada. The coalition served to strengthen the group and helped them negotiate with the government. Delegates from the different nations would assemble at the meeting place to discuss their claims and grievances. Zacharie Vincent may have attended such meetings as the ambassador of the Huron Council.

Vincent’s departure for Kahnawake came not long after and may have been influenced by the proclamation of the Indian Act of 1876, a statute that marked the culmination of the campaign to assimilate Aboriginal peoples, seize their lands, and move their communities into reserves. When he left Jeune-Lorette, the artist may also have been seeking to explore new opportunities for the exhibition and sale of his artwork. He is known to have benefited from the support of a patron, William George Beers, a dentist and politician now recognized as the “father of modern lacrosse.” At this time Beers offered to pay his train fare to Montreal; Vincent declined, preferring to pay his own travel costs. The journalist and art historian André-Napoléon Montpetit also reported that in 1879 Vincent was offered financial assistance for travel in Europe—an offer he refused without regret: “Such propositions only brought a smile to Cari’s [Zacharie’s] lips.”

His obituary states that he died in 1886, after a stroke, in the Marine and Emigrant Hospital in Quebec City.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements