Daguerrotypes and calotypes, the first photographic processes, arrived on the scene in 1839 and quickly captured the attention of the public. Although critics recognized these new technologies would change the way people engaged with the world, they debated their artistic merit and commercial applications. The first photographers in Canada were European and American immigrants or tourists who introduced these new techniques and processes through business ventures or informal apprenticeships. From portrait studios mass-producing cartes-de-visite to amateurs taking family snaps with celluloid roll film, photographic technologies and techniques have distinctively shaped how photography was practised in Canada.

Daguerreotypes and Calotypes

When the daguerreotype process was introduced to the public in January of 1839, it quickly captured international attention. Developed in France by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce (1765–1833) and Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (1787–1851), the daguerreotype is a one-of-a-kind image made on thin sheets of silver-plated copper. Daguerreotype cameras were essentially lightproof wooden boxes with simple lenses that produced a crisp image with a mirror-like reflective finish. The surface of a daguerreotype is fragile, so they were usually covered with glass and kept in cases or frames, giving them a precious quality. The daguerreotype was the first widely used photographic process in Canada and the first commercially viable format.

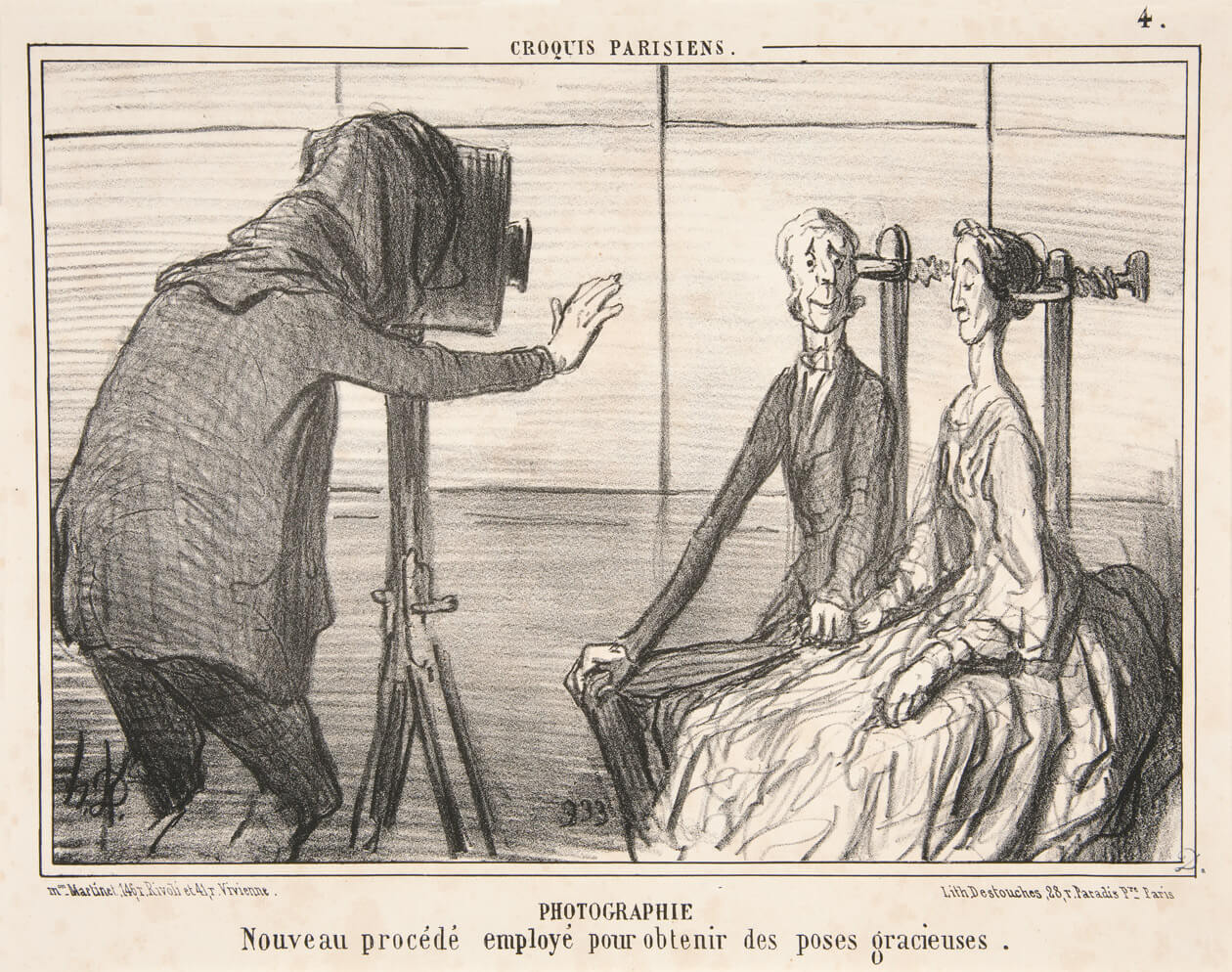

News of the technology reached North America in April 1839, when the New York Observer published a letter written by American artist and inventor Samuel Morse (1791–1872), who had visited Daguerre and witnessed his invention in France. In May, Morse’s letter was reprinted in a Toronto newspaper, the Patriot. The following year, Canadian newspapers began running advertisements for commercial daguerreotypists, many of whom were travelling entrepreneurs from the United States. By the early 1850s, daguerreotype studios were found in every major city throughout the Province of Canada. At first, exposure times were long and sitters often appear constrained, but with technical improvements, they are seen in more natural poses, such as in the portrait of the Kirkpatrick family. Especially popular for portraiture, the daguerreotype was the dominant photographic process in British North America until 1860.

The other early photographic process was the calotype, developed by William Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877) in England in 1841. This process produced a paper negative that could be printed on sensitized paper to create a photograph. Although the calotype process was never widely used in Canada or the United States, it provided the basis for subsequent photographic processes because it was easily reproducible.

The Wet Plate Process and the Expansion of Professional Photography

Over the course of the 1850s, the daguerreotype process was replaced by the collodion wet plate process. The wet plate process combined the sharp focus of the daguerreotype with the reproductive possibilities of the calotype, so it was well suited for commercial and bureaucratic use. Developed in England by F. Scott Archer (1813–1857) and in use from 1851, the wet plate process produced negative images on glass plates. With its short exposure times and sharp, detailed negatives, it was easier to obtain consistently good results with the wet plate process than with earlier methods, although it still required a knowledge of chemistry and considerable equipment. As an alternative to daguerreotypes, the main benefit of the wet plate process was its reproducibility. Using glass plate negatives, photographers could produce paper prints with a greater ease and detail than was possible with paper negatives created with the calotype process.

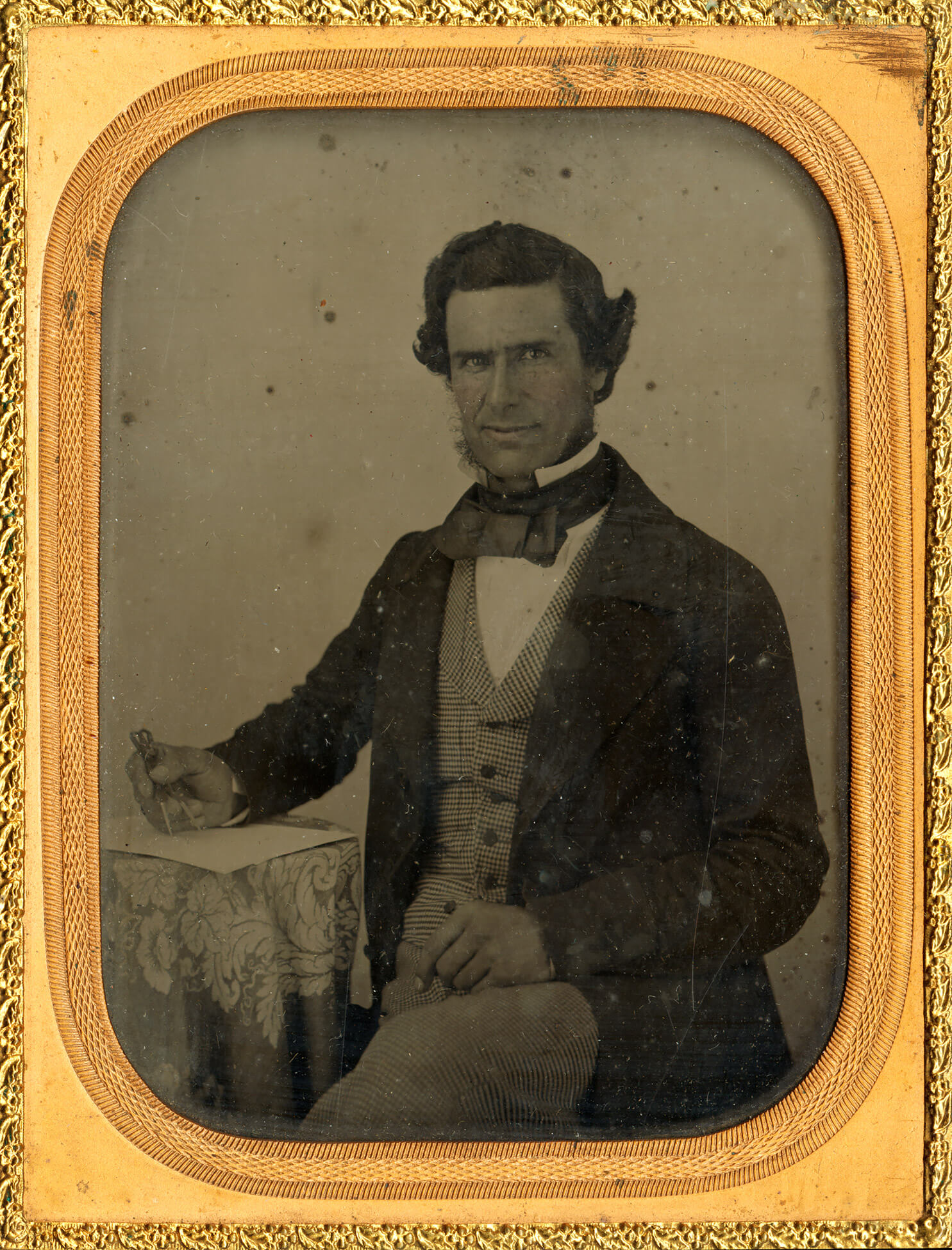

A chemical variation on the wet plate process transformed negatives into positives, and these were shown with a black backing in a decorative case, similar to daguerreotypes. This format, known as the ambrotype, was especially popular for portraiture in Canada in the late 1850s. Ambrotypes were relatively simple and inexpensive to make because there was no printing involved, and their surface was not as reflective as the polished silver of daguerreotypes.

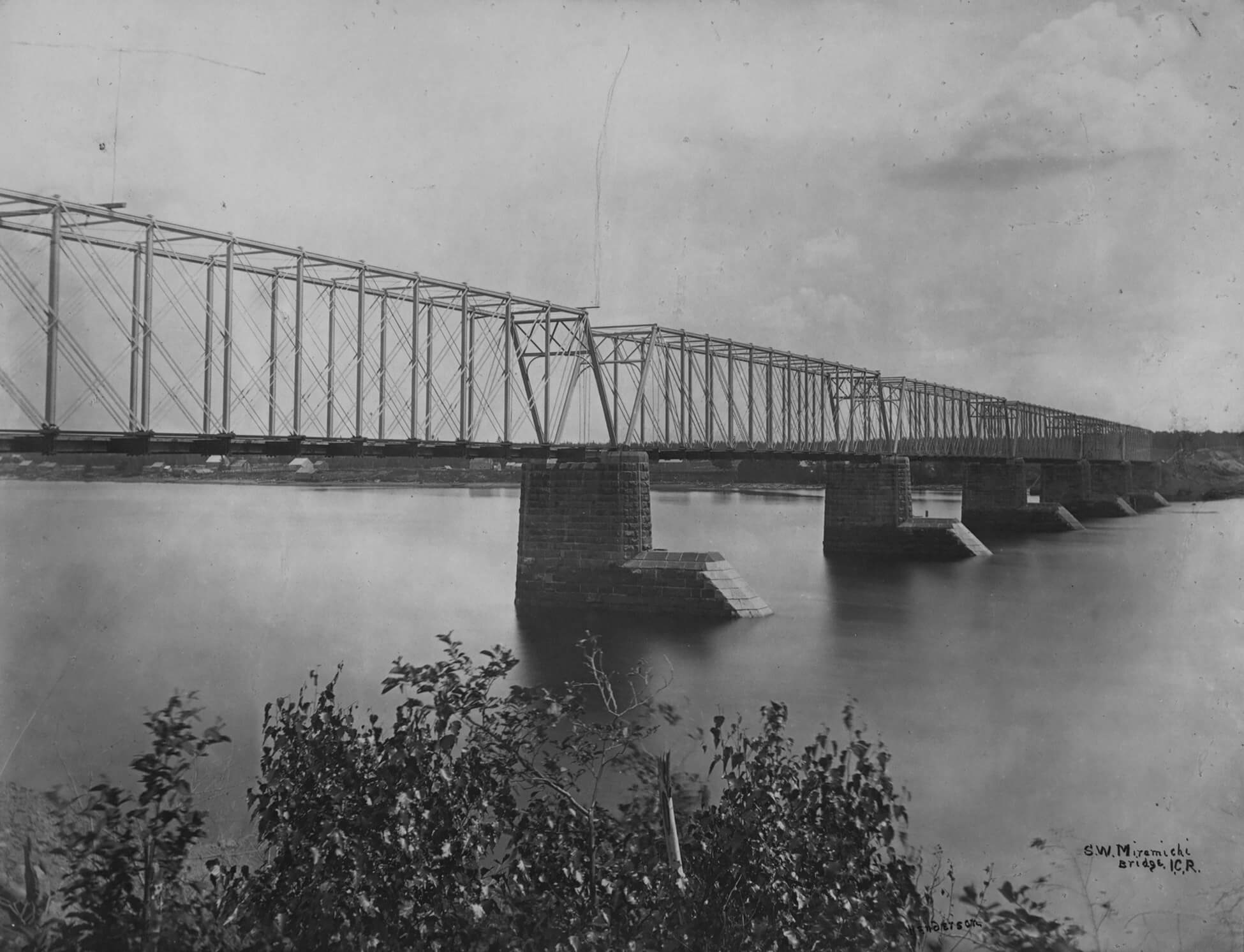

Until the end of the nineteenth century, most paper negatives and glass plate negatives were translated into positive prints using contact printing, which involved exposing light-sensitive paper while in direct contact with a negative. The resulting print has the same dimensions as its negative. The light-sensitive paper favoured by photographers during the second half of the nineteenth century was albumen printing paper, which was treated with a solution of egg whites and silver salts. Albumen prints were glossier than other papers, and this paper remained popular until the end of the nineteenth century, when it was replaced by gelatin paper. In the poetic depiction of a railway bridge over the Miramichi River by Alexander Henderson (1831–1913), the paper’s delicate sheen contributes to the atmosphere of the scene. With gelatin silver prints, the light-sensitive silver salts were bound by gelatin as opposed to egg whites. The gelatin silver prints were more stable than albumen prints because they did not contain sulphur, which caused paper to yellow over time. In addition, gelatin silver papers were more easily manufactured and distributed.

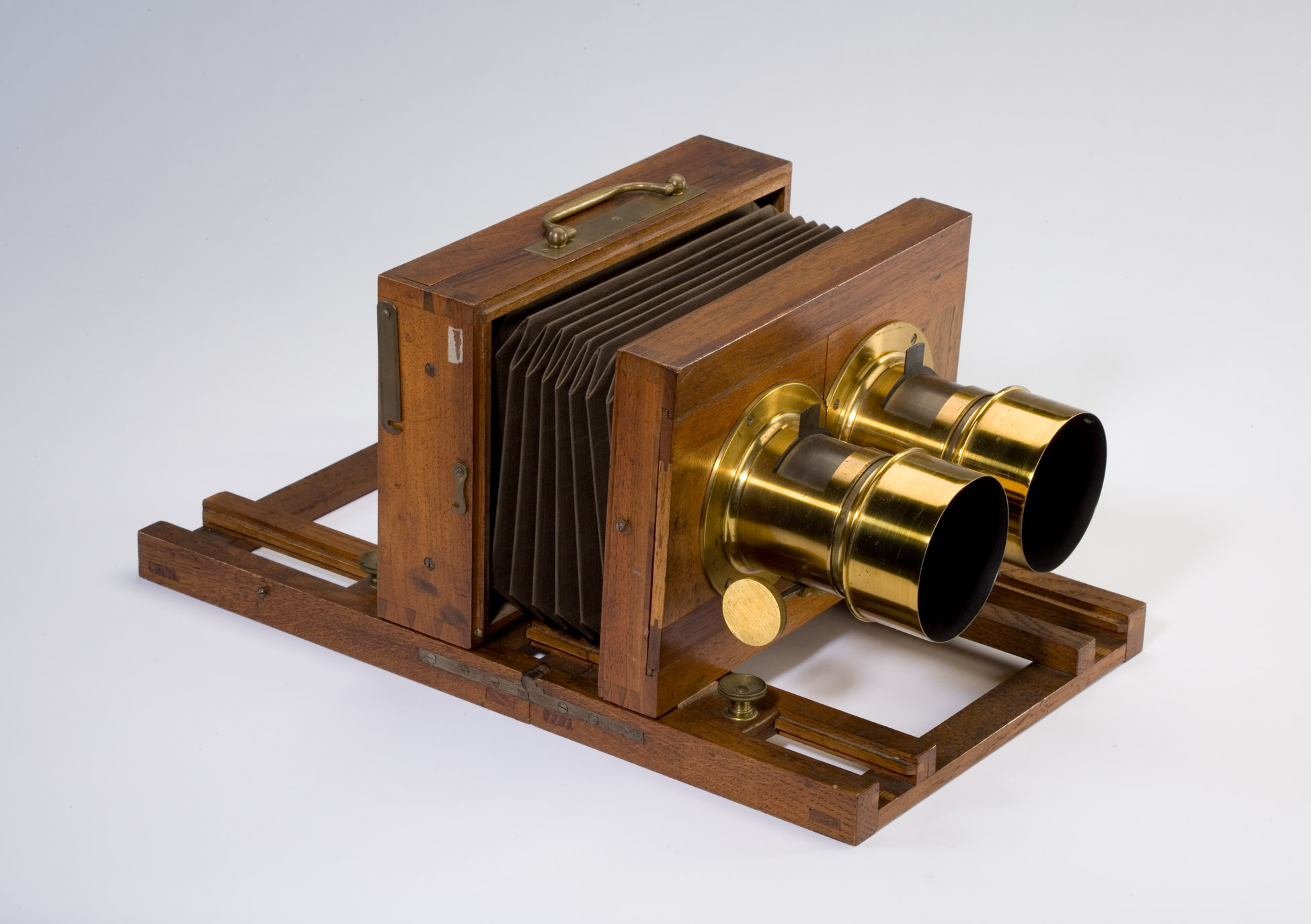

Starting in the late 1850s, Canadian photography studios found success with new formats made using the wet collodion process. Stereographs, cartes-de-visite, and cabinet cards became popular, and they ushered in the beginning of mass production in photography. Stereographs consist of two photographs of the same subject taken at slightly different angles to produce the illusion of depth when viewed through an optical device called a stereoscope. They were relatively inexpensive to produce, and scenic views and other subject matter were sold in most photographic studios. Louis-Prudent Vallée (1837–1905) was a popular stereographer who catered to tourists visiting Quebec City and the surrounding region, creating images such as La Porte Saint-Louis, Québec, c.1879–90.

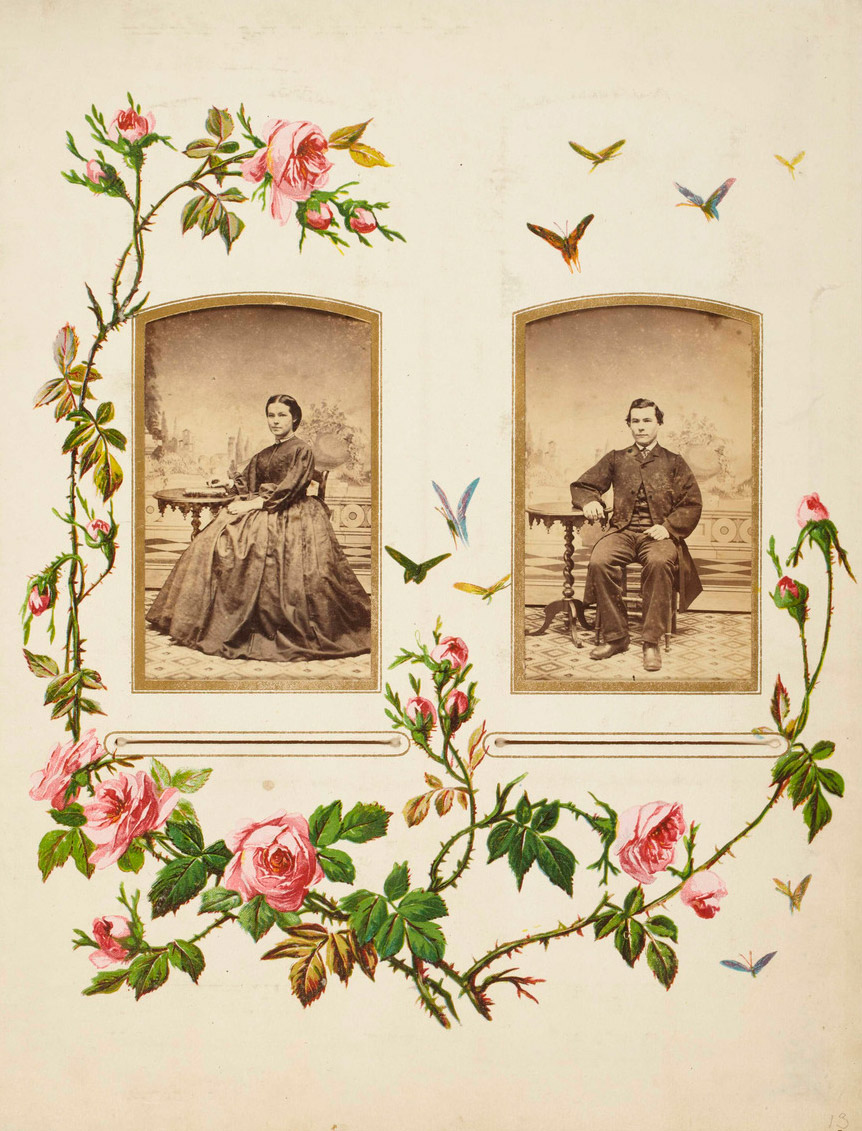

The novelty of the carte-de-visite, or visiting card, was fully embraced for portrait photography. Patented in France in 1854 by André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri, this inexpensive format was quickly adopted by studios in Canada. Cartes-de-visite were produced with a special camera that could take eight or more images per plate. This greatly increased the productivity of the photographer, and it allowed for the division of labour, so that relatively unskilled workers could do the cutting and printing necessary to produce the final product. Posing was formulaic and the process was quick, in part because facial expressions were not important in images so small. Nonetheless, acclaimed studios such as the Livernois Studio (1854–1979) still managed to produce elegant images.

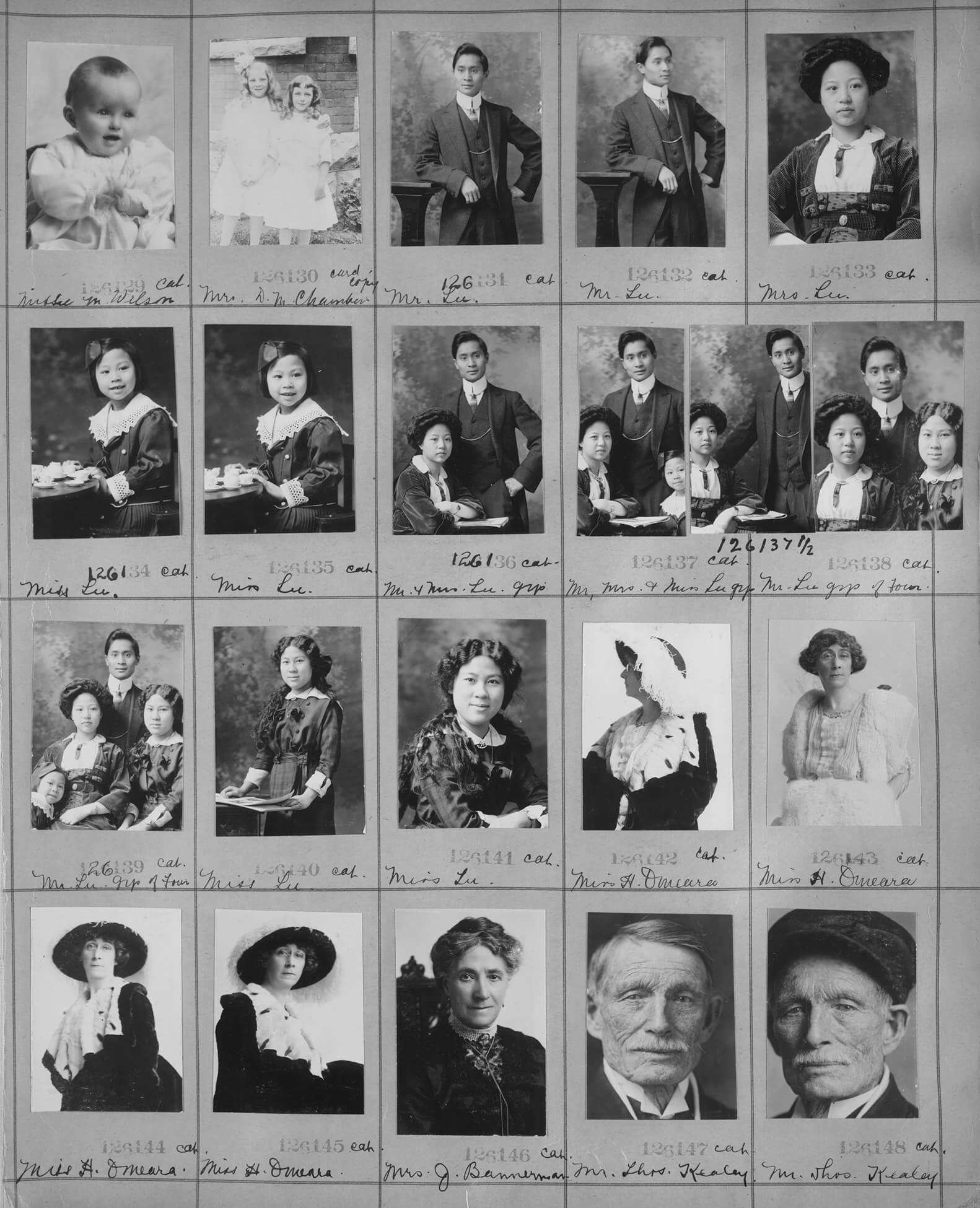

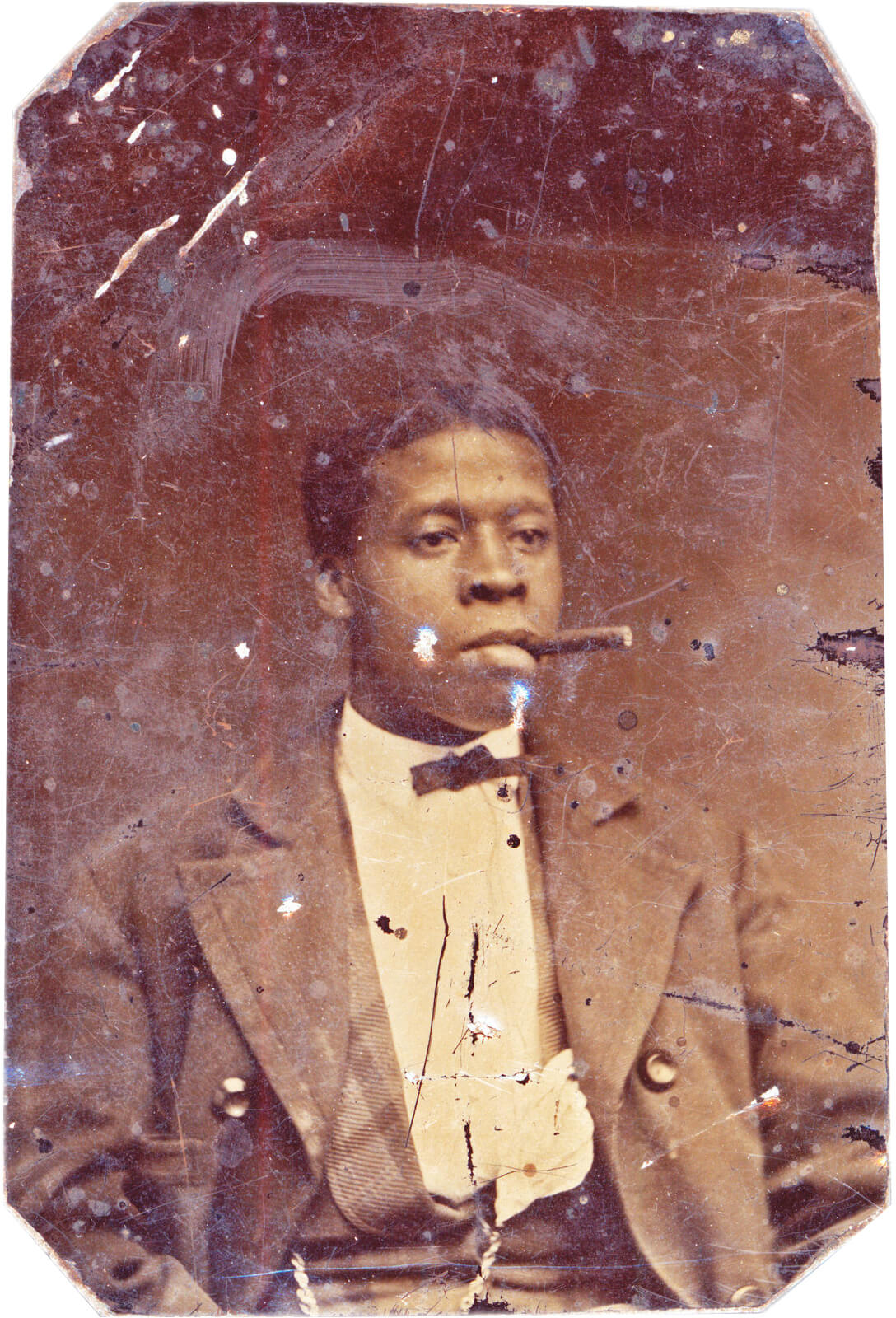

The 1850s also brought the rise of the middle class, and many families began creating photographic albums filled with the likenesses of family members, friends, and even celebrities. The commercial success of the carte-de-visite inspired the introduction of cabinet cards in the 1860s. These took essentially the same form as the carte-de-visite, only they were four times larger. The increased size allowed for greater detail, which offered the opportunity for a variety of poses and settings to display a sitter’s identity, as in this portrait of Reverend Hawkins, an abolitionist and pastor who lived in Amherstburg, Ontario. As commercial studios expanded, they created albums of proofs to keep track of photographs, so clients could browse the selections available for purchase after a sitting.

An even less expensive version of the wet collodion process was the ferrotype, more commonly known as the tintype. First introduced in the early 1850s, these were made in a variety of sizes on black-lacquered sheet iron. Tintypes were often used to make portraits, and itinerant photographers such as Duncan Donovan (1857–1933) sold them as keepsakes to working-class visitors at fairs and tourist destinations. They were popular and common photographs in North America because they were durable and relatively easy to make, but for many years they were not widely collected by institutions nor studied. Recent scholarly attention to everyday uses of photography, however, has shown there is much to learn from these modest objects. For instance, the exhibition Free Black North, held at the Art Gallery of Ontario in 2017, explored how tintypes offered Black people living in small-town Ontario a means of expressing their aspirations, such as in the image of the man smoking a cigar.

The wet plate process was used outside of the studio setting, but not without significant challenges. When Humphrey Lloyd Hime (1833–1903) was documenting the 1858 Assiniboine and Saskatchewan Exploring Expedition, he had to cart all the fragile and cumbersome equipment for making and developing wet plate photography. The equipment included the cameras and a tripod, along with glass plates, chemicals, and a darkroom tent. The process also required clean water for treating and developing the negatives. In spite of these difficulties, Hime achieved some good results, and a selection of his photographs of the prairies were published in the expedition report by Henry Youle Hind (1823–1908).

During the 1850s and 1860s, most photographically illustrated books featured tipped-in albumen prints that were pasted onto pieces of heavy card stock bound with the other book pages. The first Canadian literary work illustrated with albumen prints was published in 1865. Titled Maple Leaves: Canadian History and Quebec Scenery by James MacPherson Le Moine (1825–1912), the book included photographs by Jules-Isaïe Benoît Livernois (1830–1865), which showed selected locations described in the text.

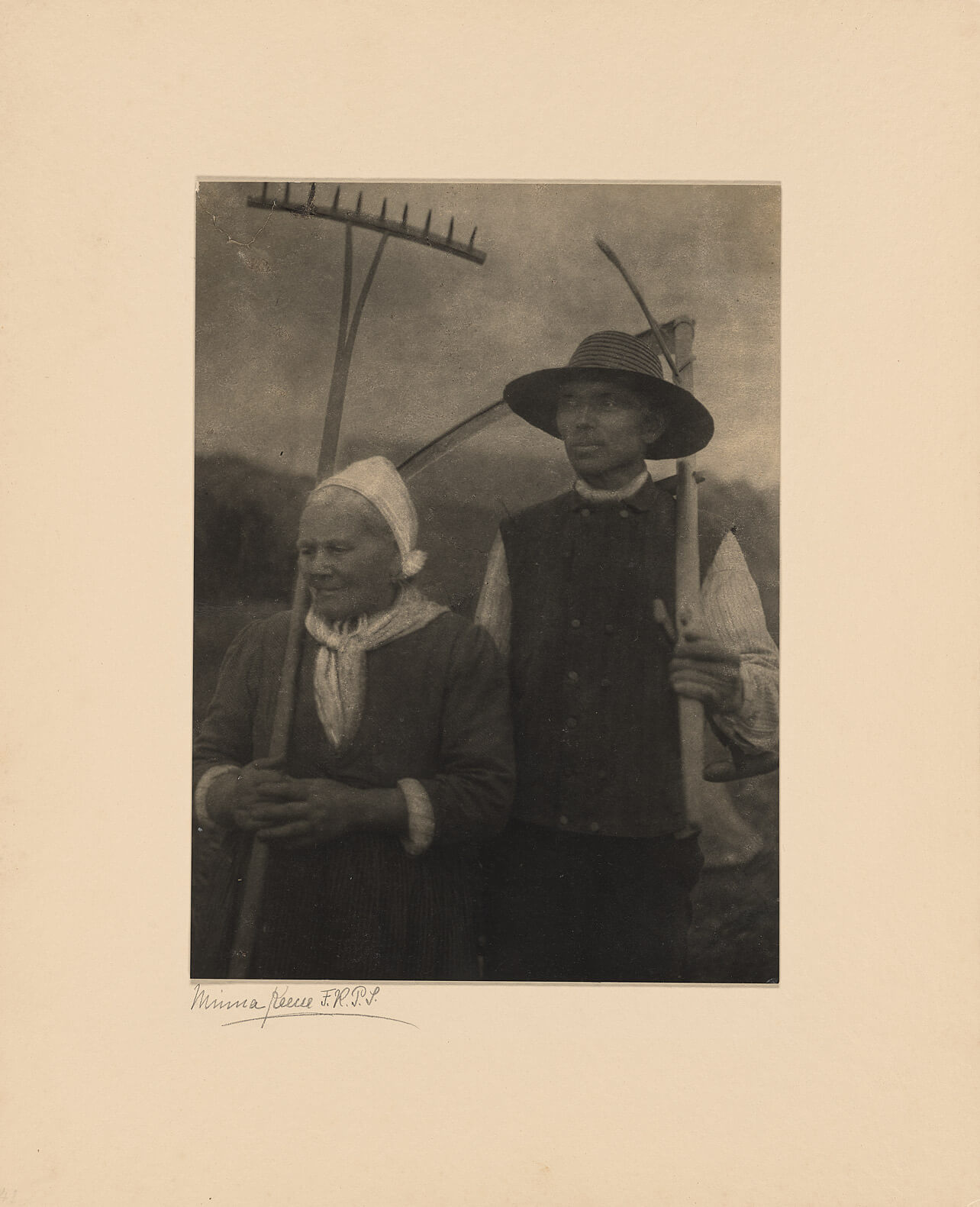

Starting in the 1860s, photomechanical processes were developed and applied to book illustration. A photomechanical print is a photographic image printed in ink. One of the earliest photomechanical processes was carbon printing, where a photographic image was transferred to a paper support from carbon tissue, a piece of paper coated with light-sensitive pigmented gelatin. Carbon prints were suitable for reproduction because the results were predictable and stable, although the process was labour intensive. This print was most often used in large-scale commercial production or by some Pictorialist photographers who were interested in its potential for painterly effects. Minna Keene (1861–1943) used carbon printing to produce evocative images such as Harvesters, c.1905, and Fruit Study, c.1905.

Carbon printing and other extant photomechanical printing processes were not always practical for commercial printers, and most books, newspapers, and periodicals were illustrated by woodcuts or wood engravings until the development of halftone printing. This process involved translating a photograph into a pattern of dots that could be printed with a letterpress. The first halftone reproduction of a photograph, a portrait of Prince Arthur by William Notman (1826–1891), appeared in the inaugural issue of the Canadian Illustrated News on October 30, 1869. With the development of halftone printing, it became easier to reproduce and disseminate photographs to a wide audience.

The Dry Plate Process and New Potential for Photography

The main technological development of the 1870s was the introduction of the dry plate process. It was far less restrictive than wet collodion because glass plates coated with a light-sensitive gelatin could be dried and exposed up to several months after they were prepared. This advancement allowed for the mass production and distribution of glass plate negatives and freed photographers from their darkrooms stocked with chemical solutions. However, an initial lack of standardization by manufacturers created challenges for photographers, and some professionals stuck with wet collodion for years. With further technical refinements, the dry plate process became more reliable and was adopted as the new standard.

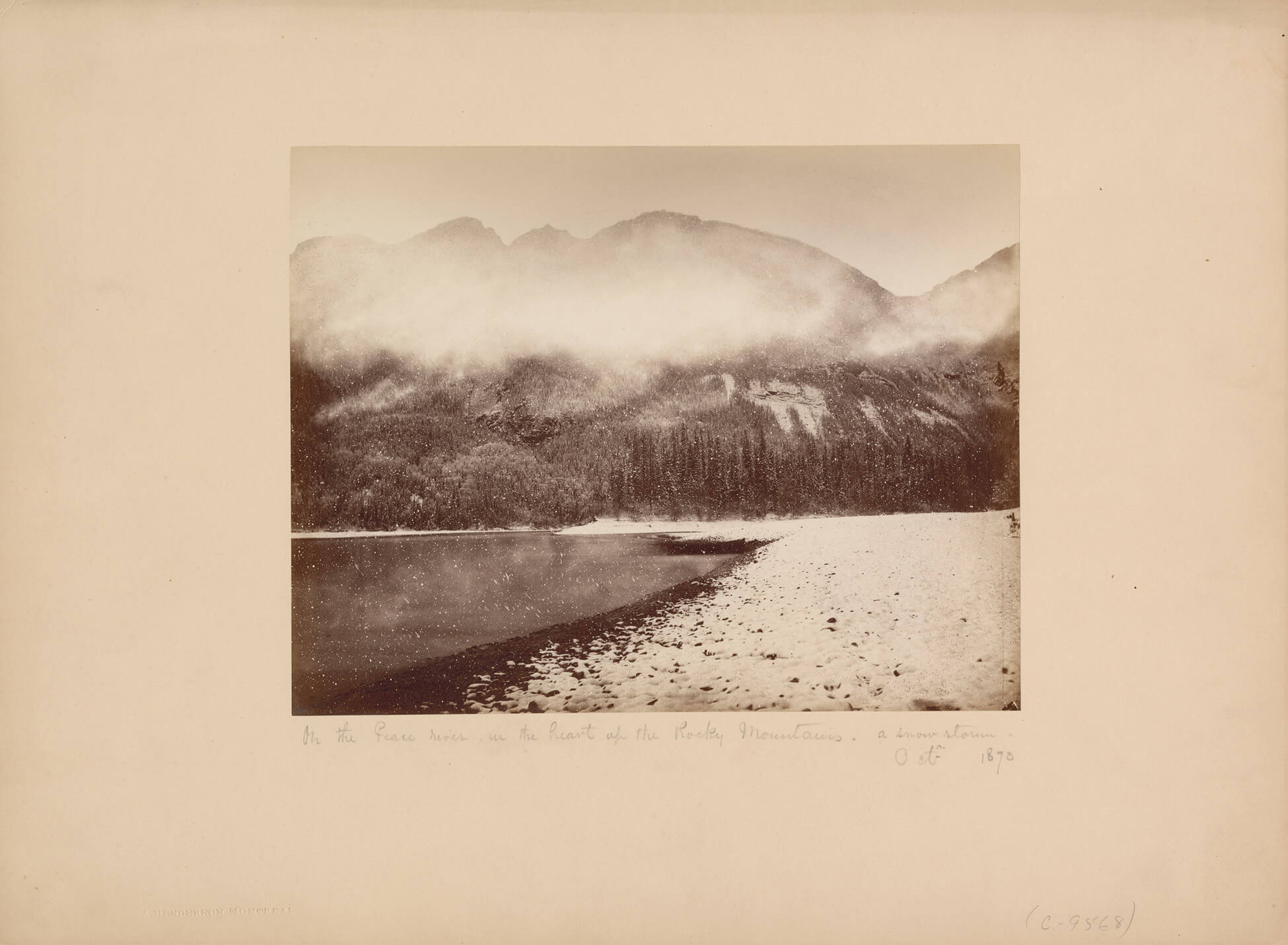

The dry plate gelatin process was a game changer in Canada because it was more mobile and remained stable, even during extreme weather and in harsh environments. Charles Horetzky (1838–1900), who was hired to photograph possible routes for Canadian Pacific Rail tracks through northern Saskatchewan and Alberta, was only able to produce photographs in freezing temperatures successfully because he used the dry plate process. Compared to the wet plate process, commercially prepared dry plates were faster and easier to use, and in the 1870s, it became routine for geologists and surveyors working for government agencies such as the Geological Survey of Canada (GSC) to take photography supplies with them on their expeditions. This ease of use in turn led to other advancements. Édouard Deville (1849–1924), the Surveyor General of Canada, recognized the potential of the dry plate process for topographical surveys of the west. Under his direction, surveyors applied the gelatin process to photogrammetry, a method for gathering topographical data, which allowed them to efficiently map a vast mountainous region.

The relative ease and affordability of the dry plate process also made photography more accessible to amateurs like Mattie Gunterman (1872–1945) and, in the 1880s and 1890s, many people enthusiastically embraced this new technique. Photographers in rural communities took up photography, with families, friends, livestock, farms, and landscapes as popular subjects, such as in images by Marsden Kemp (1865–1943), an amateur photographer in Kingston and Picton, Ontario.

With the easy-to-use technology and new lightweight, hand-held cameras, more women also began to pursue photography as a pastime. However, instead of challenging gender conventions, this merely reinforced the prevailing idea that women were not suited to the more technically complex processes. This stereotype persisted even though many women were employed in photographic studios. In Notman’s Montreal studio in the 1870s, for instance, women held many positions and were involved in printing, retouching, and mounting photographs, along with administrative tasks.

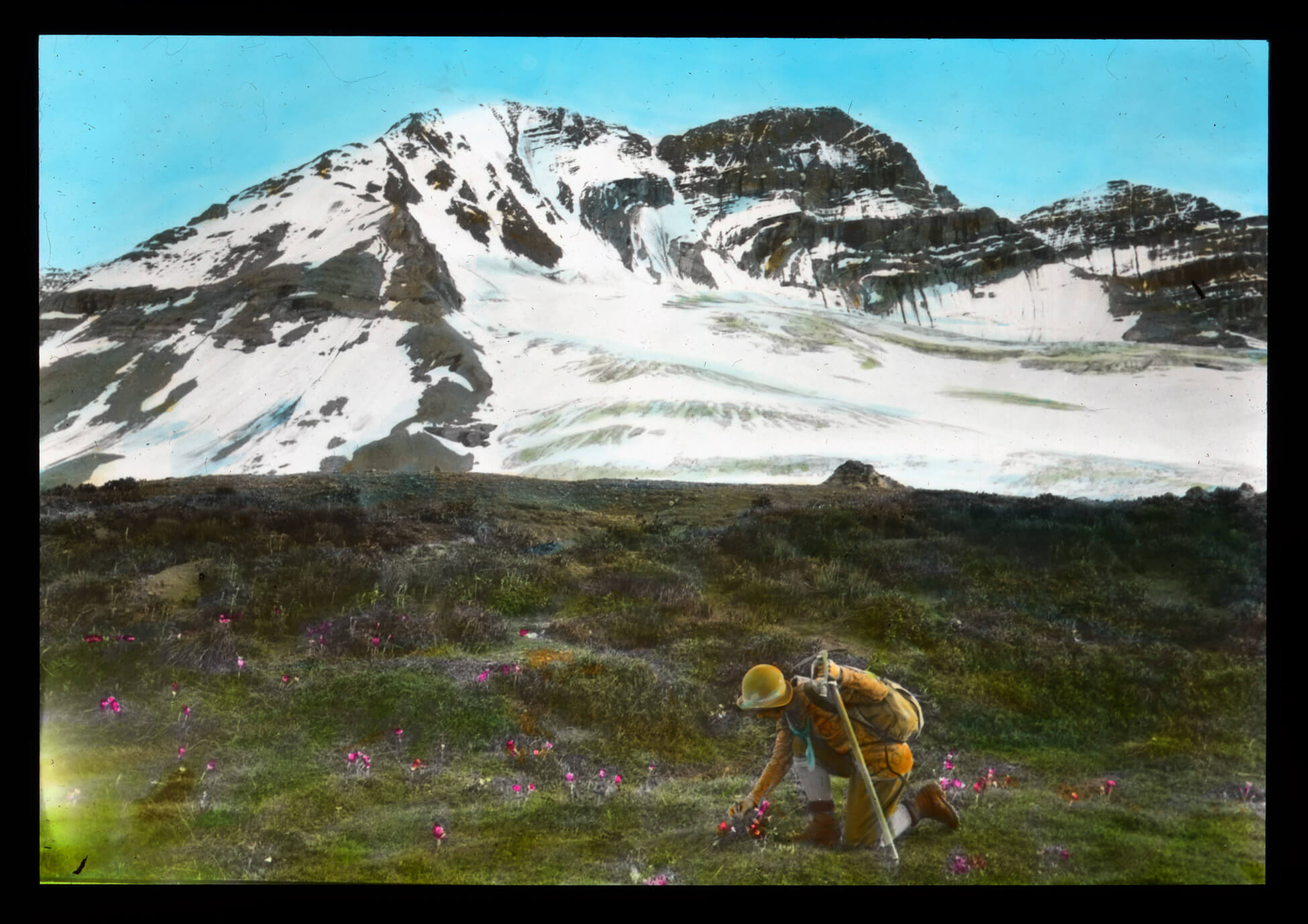

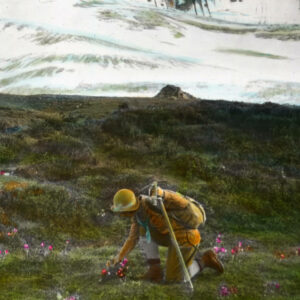

The dry plate process was also used to produce glass lantern slides, often referred to as “magic” lantern slides. They were shown at public lectures and functioned as both education and entertainment. Lecturers travelled to large cities and small towns across the country and abroad, sharing news and views. Some slide shows were sponsored by companies and others were organized by individuals. The Winnipeg Exhibition Company, for instance, presented a travelling lantern slide lecture showing “photographic views along the CPR.” Mary Schäffer (1861–1939) presented lantern slides, such as this one of a hiker picking flowers, in lectures on her adventures in the Rockies to audiences in Canada and the U.S. in the 1910s.

On the Prairies, lantern slide lectures on new products and farming methods were an important source of information. From 1914 to 1922, the University of Saskatchewan delivered a “school on wheels” program, sponsored by the Department of Agriculture. Railroad cars were set up as travelling theatres, called “Better Farming Trains,” and these would travel to remote regions of the province, reaching audiences of approximately thirty to forty thousand each summer. Researchers working for the GSC made lantern slides during their excavation of dinosaur remains in the Badlands of southern Alberta, and these helped to explain archaeological procedures, such as the preparation of fossils for shipment to Ottawa.

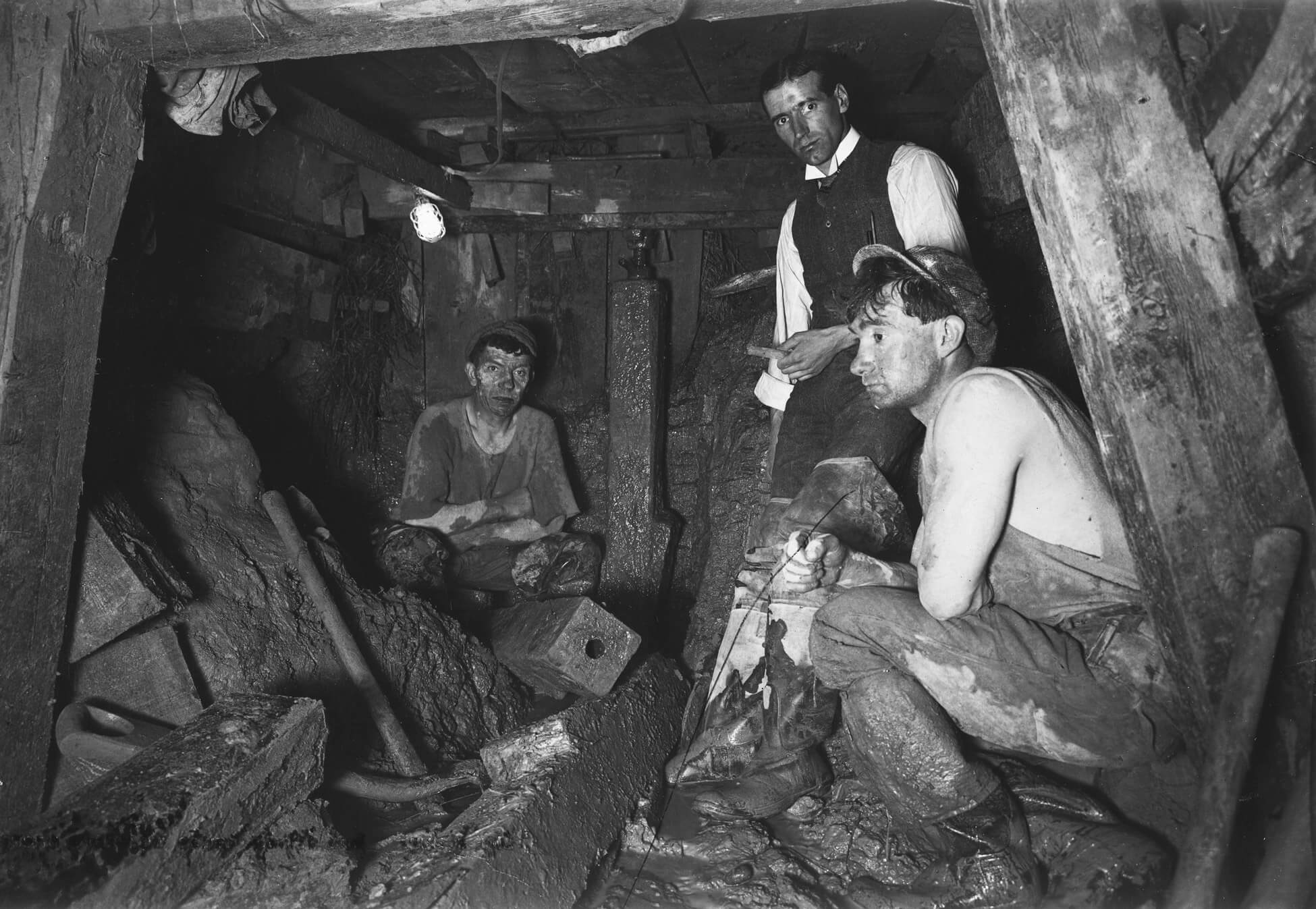

By the end of the nineteenth century, new technologies also expanded the capabilities of photographers to reveal dark domestic interiors and subterranean storm sewers. The dry plate process was used in conjunction with other technological developments, including magnesium flash powders and electrical lighting. Introduced in the 1880s, magnesium flash powders were mixed with an oxidizing agent that made them combustible to a small spark. Though dangerous, flash powders enabled photographers to practise flash photography outside of the studio setting, where artificial light was common by the end of the century. The City of Toronto’s first official photographer, Arthur Goss (1881–1940), used magnesium flash powders and, eventually, flashbulbs to photograph the living conditions of the city’s residents and to document the construction of its sewers.

A key feature of the dry plate gelatin process is its permanence over time. Both the glass plate and the gelatin chemistry are relatively stable, and scholars are able to study the work of many late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century photographers in Canada because they used this process. Even when prints have not survived, the glass plate negatives have. There are numerous stories from across the country of boxes of glass plate negatives discovered in attics, basements, and garages after many decades. The glass plate negatives of the Hayashi Studio (1911–1935) in Cumberland, British Columbia, for instance, have enabled historians to reconstruct aspects of Japanese immigrant history before the period of internment camps during the Second World War. Mattie Gunterman’s glass plate negatives survived years of neglect before they were recovered, providing a unique perspective on settler life.

The discovery in the 1980s of glass plate negatives taken on the Prairies by Black photographer William S. (Billy) Beale (1874–1968) also allows a reassessment of one man’s legacy and offers new insight into the history of a Manitoba community. Even though photographers from marginalized backgrounds were under-recognized in their own time and their work was not preserved by government institutions, we can acknowledge their important contributions today because their glass plate negatives still exist.

New Perspectives Through Celluloid Film

A major breakthrough in the late 1880s expanded the practice of photography once again. Although the stability of the dry plate process was advantageous, there were drawbacks to the glass plate support used for the gelatin emulsion. The glass added to the weight of a photographer’s equipment and was prone to breakage. Experiments to find alternatives eventually led to the creation of a new material: celluloid, which was initially available in sheets before it was made into rolls.

Camera technology advanced alongside this new film technology. Hand-held cameras had become possible with the faster exposure times of commercially produced gelatin dry plates in the 1870s, and in the late 1880s, new models were introduced that used roll film. The most popular of these was the Kodak camera, introduced by George Eastman in 1888. Initially, this small, affordable hand-held camera was equipped with a roll holder spooled with enough sensitized paper to produce one hundred negatives. The following year, Kodak cameras were fitted with celluloid roll film. As suggested by the Kodak slogan “You press the button, we do the rest,” consumers could send their film back to the company where it would be developed and printed for a small fee.

Kodak box cameras were easy to use and were marketed to women especially. Amateur photographers often shared their knowledge and enthusiasm for photography with one another, sometimes photographing each other as they practised. However, even though the photographic industry made women more visible as photographers, it reinforced the idea that “serious” photography was too complicated for women and it relied on current conventions of femininity to sell products.

The small number of women who achieved commercial success as photographers also had to navigate gender stereotypes. When professional women were described as talented photographers, critics attributed this to supposedly feminine qualities, such as their artistic abilities or skill at relating to others, rather than to their technical expertise. Even internationally recognized photographer Minna Keene was praised in a 1926 Maclean’s magazine story as a “home-loving wife and mother,” and although the author recognized her artistic talent, he made it clear that he thought a woman should not concern herself with commercial success.

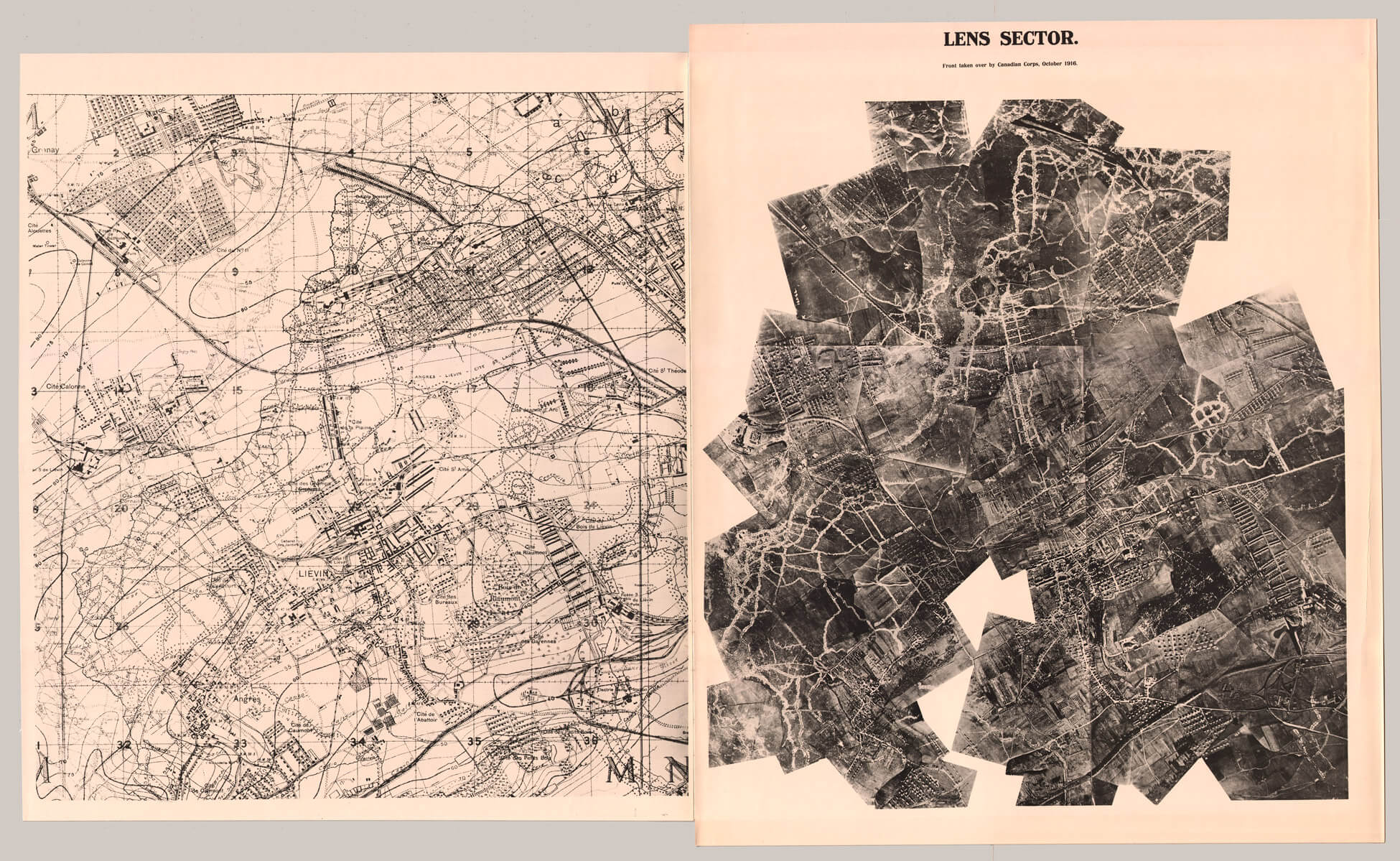

Hand-held cameras and celluloid roll film were also important during the First World War. Many young men carried the newly released Vest Pocket Kodak camera with them to the front lines, and in spite of censorship regulations, some soldiers made photographs and assembled albums. Photography was also used for tactical purposes during the war. This was the first war to use aviation technology, and military strategists used aerial photographs and other formats, such as battlefield panoramas, for reconnaissance and intelligence-gathering. For the most part, these photographs were not seen by the public until after the war; however, the public was informed about the developments in technology that made aerial surveillance possible. This helped to build faith in military strategy and technology as a solution to wartime hostilities.

New commercial applications for aerial photography were also made possible by celluloid film after the Second World War. In 1946, after serving in the Royal Canadian Air Force, London photographer Ron Nelson (1915–1994) established a business specializing in aerial photography. His clients included large corporations such as Imperial Oil, Bell Telephone, and John Labatt, as well as local companies and institutions, such as the University of Western Ontario. His photographs were published in company reports, on posters, and in other promotional material.

Colour in Art and Commerce

The introduction of colour to photography during the early twentieth century dramatically changed the aesthetic and commercial potential of photography. There are a variety of colour photographic processes, each with its own distinct characteristics and applications. However, some, such as interferential photography, attributed to Gabriel Lippmann (1845–1921), were too complicated and expensive for widespread use. The autochrome, developed by the Lumière brothers and released in 1907, was the first commercially available process. This technique often produced soft, subdued colour well-suited to the Pictorialist aesthetic. Hugo Viewegar (1873–1930), who learned the autochrome process before moving to Canada in 1912, explored the expressive potential of colour in portraiture.

A variety of chromogenic film became commercially available during the 1930s and 1940s. Chromogenic film is celluloid treated with three layers of light-sensitive gelatin, each of which registers only red, green, or blue light. Kodachrome, introduced in 1935, was the first colour transparency film, and it was initially limited to commercial applications because of how expensive it was. Slides in cardboard mounts that could be projected onto a screen using the Kodaslide projector became available soon after.

Fred Herzog (1930–2019) used Kodachrome to photograph Vancouver streets from the late 1940s until the 1990s, and he delighted in the film’s distinctive red hues. However, because Kodachrome transparencies were difficult to print, Herzog’s work was rarely exhibited until digital scanning and inkjet printing made it possible to reproduce the rich subtleties of the film. With the introduction of Kodacolor in 1942, colour photographic prints could be made from chromogenic film negatives. But because colour photography was earmarked for military use during the Second World War, the artistic and commercial possibilities of these new processes were only explored in the postwar period.

After the war, colour became popular. Dye transfer printing, which was first available in 1946, is a complex and technically demanding process that involves making separations of the colours that form a print. Each colour is printed individually; those individual colours are combined in layers to create the final image. The main benefit of the process is the ability to control the colour balance to create strong, saturated hues and a glossy finish. The rich hues give dye transfer prints a graphic quality, like in George Hunter’s Wild Horse Race, Calgary Stampede, 1958, and this process was used extensively in postwar commercial photography and in print advertising.

In the 1970s, colour photography became more affordable and it was embraced by photographers who had previously worked in black and white, as well as by artists who used a range of media. Gabor Szilasi (b.1928), for instance, turned to Kodak’s Ektacolor film to explore the social and cultural significance of colour in a series of interiors. Polaroid Corporation introduced several instant colour processes using dye diffusion technology between 1963 and 1981, including the popular single-lens reflex camera, the SX-70. The instant film used with the Polaroid cameras was the result of complex chemical engineering and produced a single material artifact, but artists such as Charles Gagnon (1934–2003) created artwork such as Untitled, 1978, as a way of exploring the singularity of the Polaroid in a series.

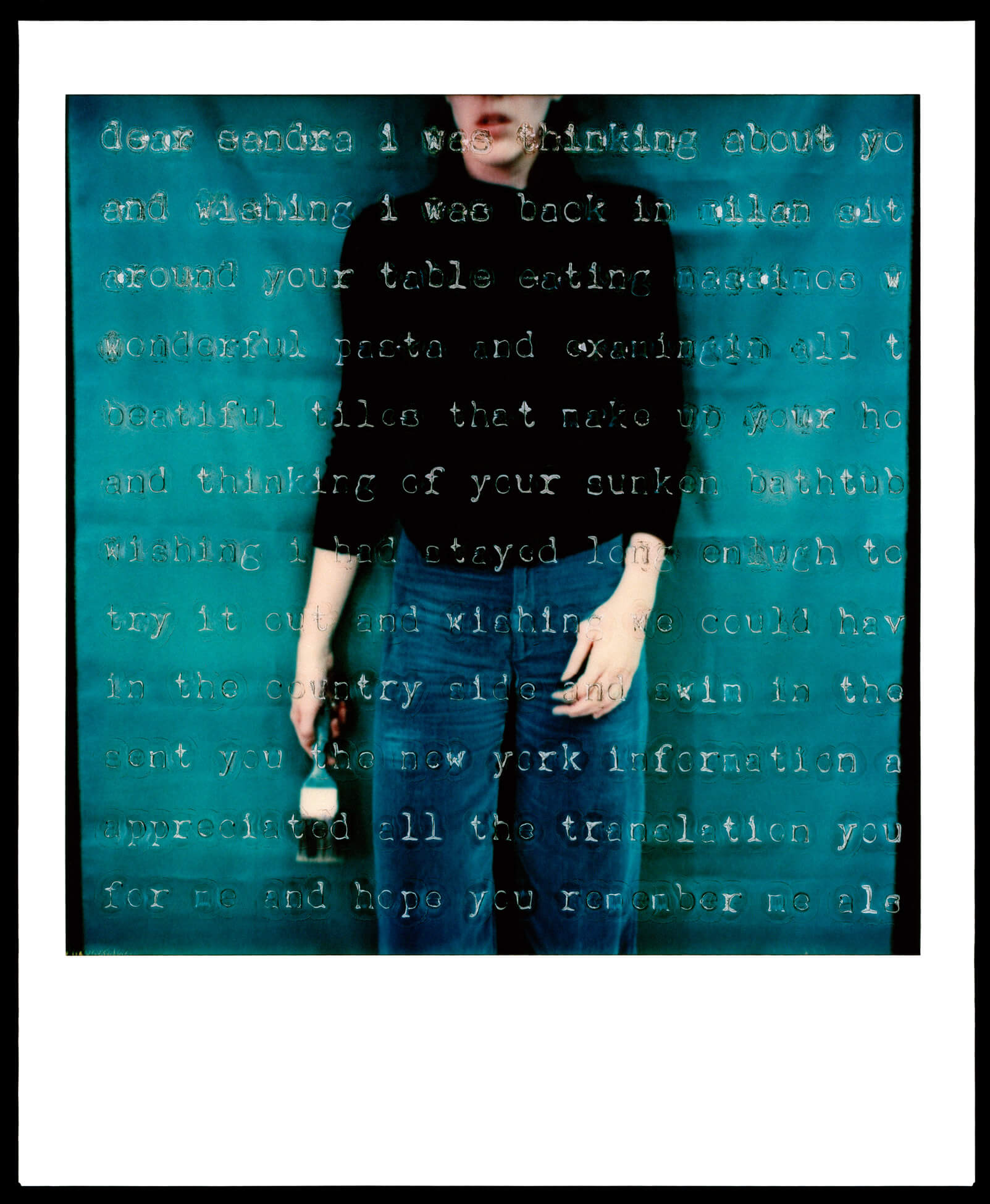

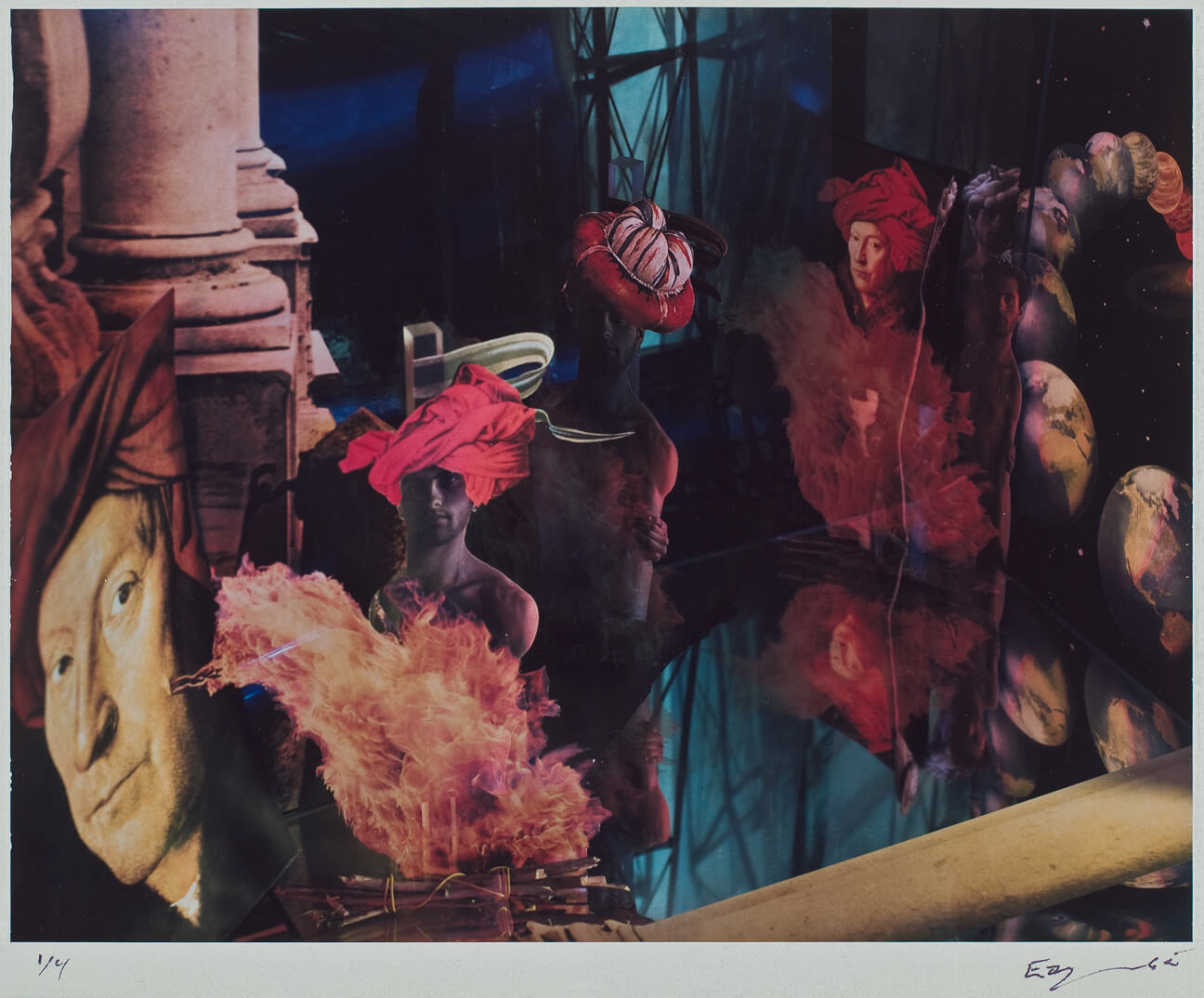

Artists experimented with these new materials and techniques, and in the process they challenged previous distinctions between photography and contemporary art. Ojibwe artist Carl Beam (1943–2005) used collage and photo-transfer techniques in his work on the impact of European colonization, and P.Mansaram (1934-2020) worked in collage to explore the effects of mass media and the diasporic experience. Ron Benner (b.1949) created photographic murals to comment on globalization and the politics of food. Ektacolor murals of enlarged Polaroid images by Barbara Astman (b.1950) combine an overlay of typewritten letters to friends with new colour processes to create visual narratives of longing. Evergon (b.1946) used a large-format Polaroid camera to create compressed compositions that reference the theatricality of academic painting. These artists, and the many others who experimented with photography in the 1970s and 1980s, ultimately transformed the status of photography within the field of contemporary art.

About the Authors

About the Authors

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements