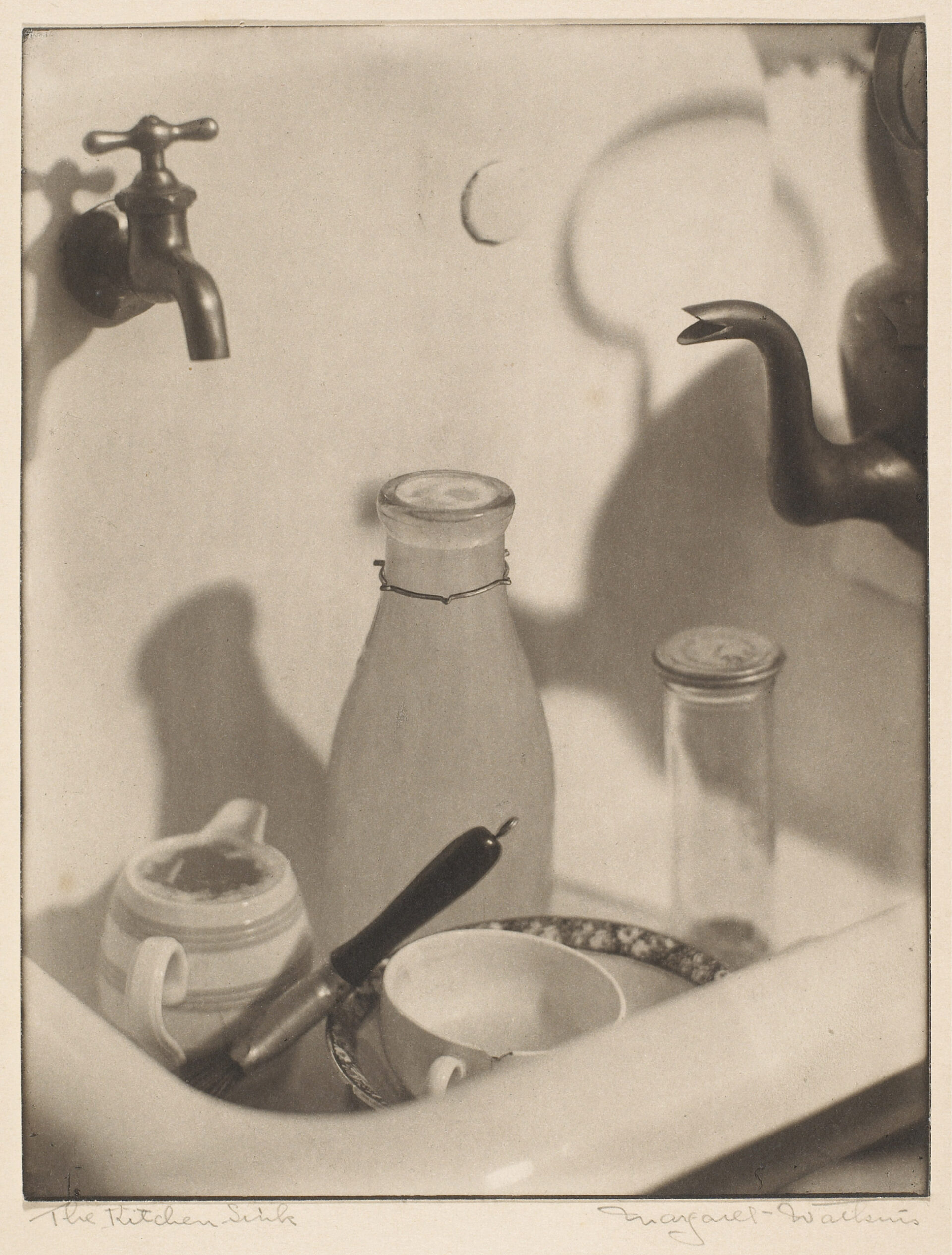

Margaret Watkins (1884, Hamilton, Ontario–1969, Glasgow, Scotland)

The Kitchen Sink, c.1919

Palladium print, 21.3 x 16.4 cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

The iconic photograph The Kitchen Sink by Margaret Watkins (1884–1969) is a beautiful image of a mess that integrates the soft focus and warm tones of Pictorialism with the dynamic composition and embrace of utilitarian subjects in modernism. The platinum process produced rich and soft grey tones and edges to the print, as opposed to the starker lines and tones of the more modern silver gelatin process. Overall, this striking work echoes how Watkins sought to balance tensions in her own photography and her brief but stellar career.

Watkins grew up in an affluent and cultured family that encouraged her artistic interests. She may have begun learning about photography from her uncle, who was active in the local camera club. However, the family fortunes changed dramatically when she was a teenager and the family struggled for several years. Just after her twenty-fourth birthday, Watkins declared in a notebook, “I am nearly domesticated to death.” She promptly left her family home to work at a series of progressive arts camps in the northeastern United States. It was in this experimental context that she studied photography, starting with landscapes and figures, before turning to the still life compositions that would define her career.

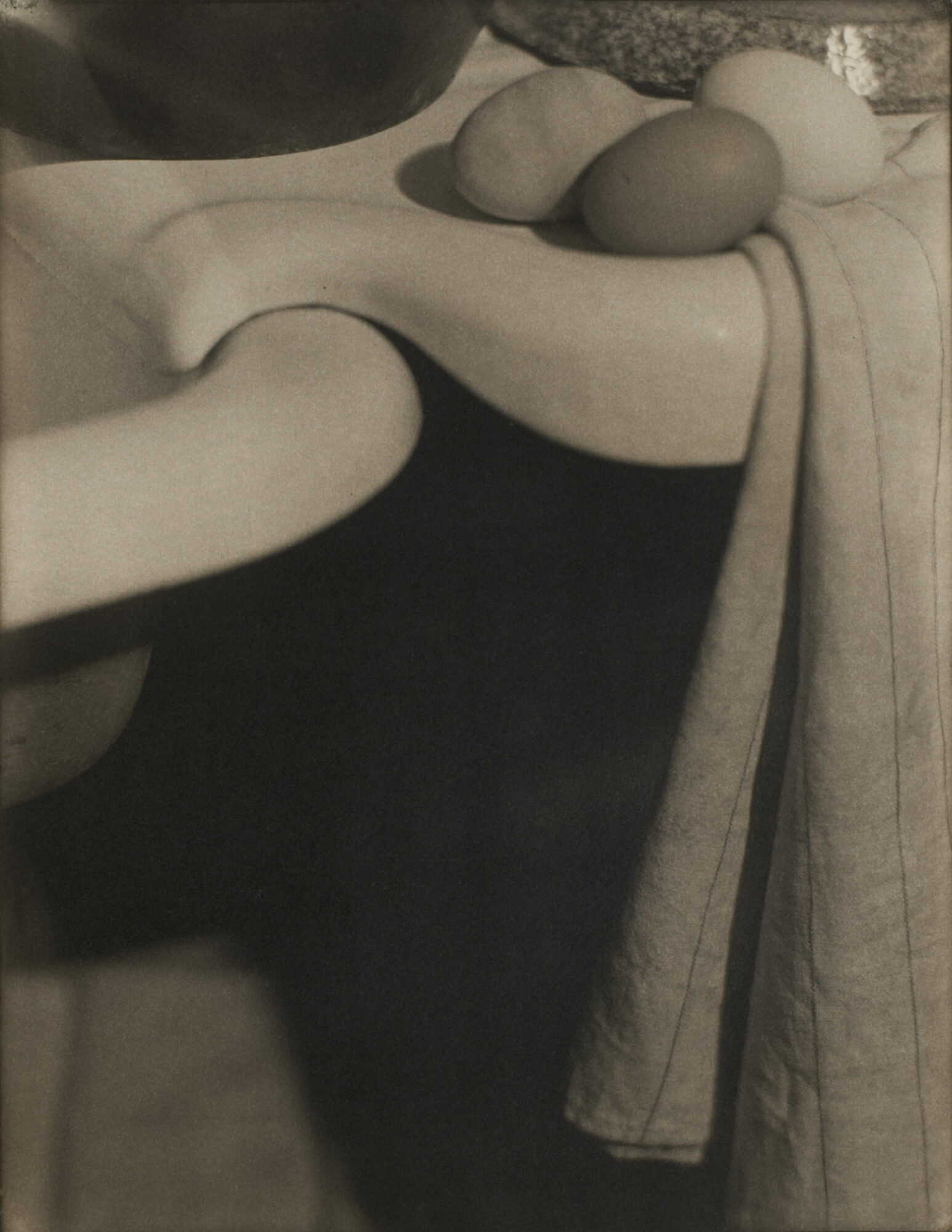

Like so many Canadian artists who would follow, she eventually made her way to New York City, where she attended the renowned Clarence H. White School of Photography. Watkins was a star student turned teacher, and famed photojournalist Margaret Bourke-White (1904–1971) was among her pupils. In her artistic practice, Watkins exhibited signed prints like The Kitchen Sink in a range of prominent galleries in New York and around the world, and photographs such as Domestic Symphony, 1919, and Design–Angles, 1919, were widely admired. However, at the same time, she also worked as a commercial photographer, creating high-profile advertisements for products as disparate as soap, cheese, and luggage.

Watkins eventually grew disenchanted with the competitive New York photography scene, so she travelled to Europe and then moved to Glasgow in 1928 to help care for her elderly aunts. She was elected an Associate member of the Royal Photographic Society and participated in a group photographic trip to the Soviet Union in 1933. She continued to make photographs through the 1930s, but these were seen only in local exhibitions.

Just before she died in 1969, Watkins gave a box to her neighbour and friend, Joseph Mulholland. When he finally opened it, some years after Watkins’s death, he was shocked to find a trove of prints with gallery stickers from numerous countries. In their decades of friendship, Watkins had never mentioned photography. Although she did not return to live in Canada, Watkins’s work and her legacy inevitably circled back to her home. Throughout her life she kept up correspondence with Canadian friends and family, and these letters are now archived at McMaster University.

About the Authors

About the Authors

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements