C.D. (Chow Dong) Hoy (1883, Guangdong, China–1973, Quesnel, British Columbia)

Kong Shing Sing on a horse on Barlow Avenue in Quesnel, c.1910

Barkerville Historic Town Archives

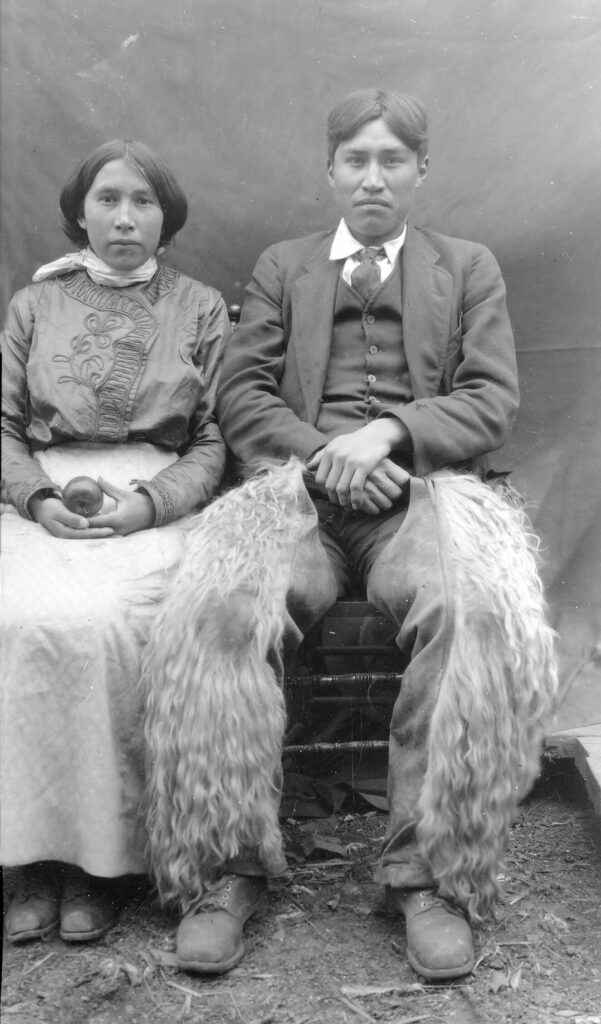

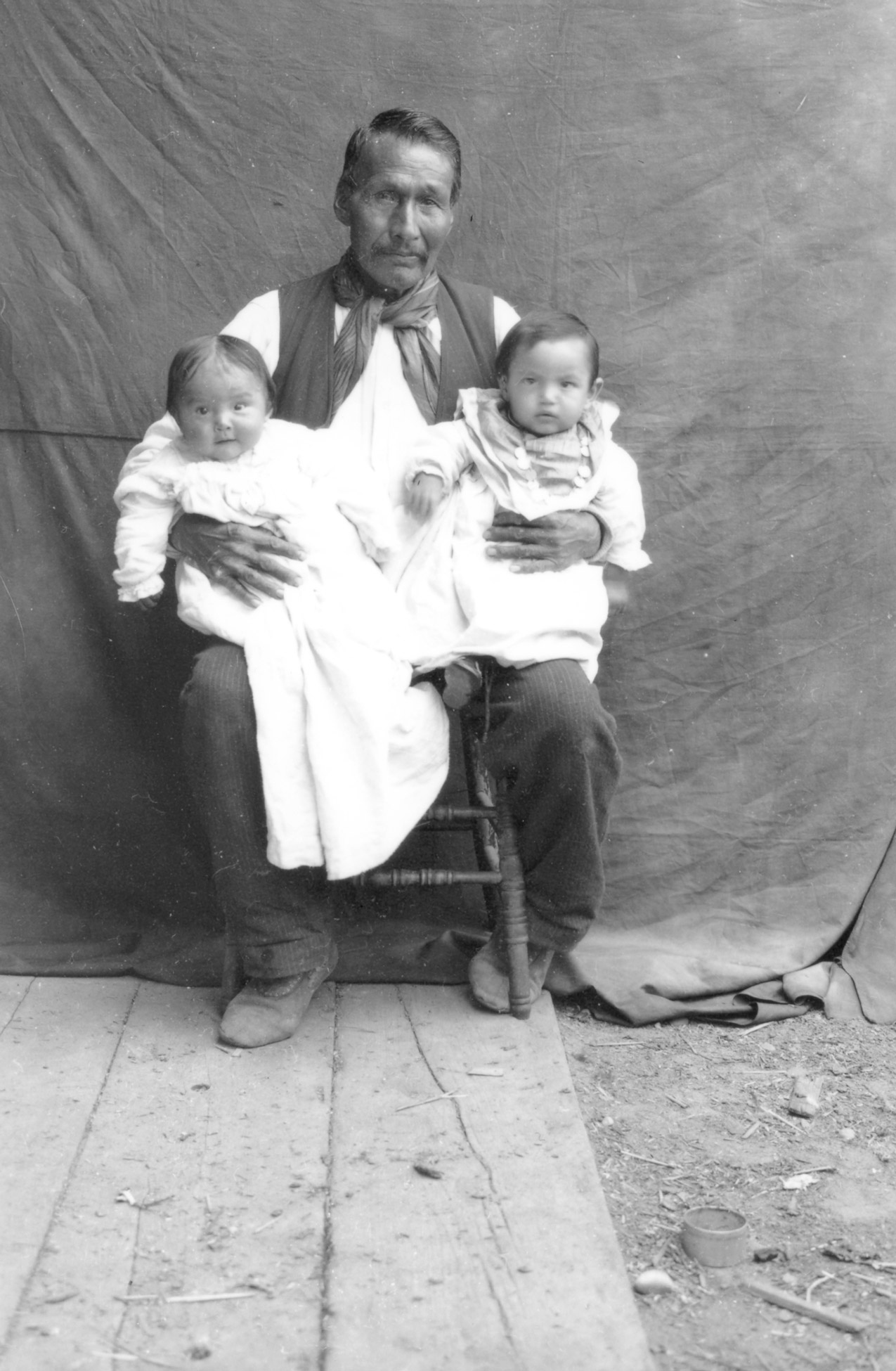

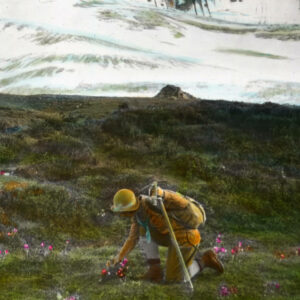

The photographs of Chow Dong Hoy (1883–1973) offer a rich visual document of people in Quesnel, British Columbia, a town on the Canadian frontier that was predominantly Asian Canadian and Indigenous at the turn of the century. The local culture is signalled in this majestic portrait of Kong Shing Sing. The subject appears on horseback, a pose befitting his position as the scion of a ranching family in the area. Sing was also a blacksmith and a proficient cowboy, and his woolly chaps derive from local Indigenous traditions—Tsilhqot’in Chief William Charleyboy wore a similar pair when he sat for Hoy. One of the first photographers of Chinese descent to work in Canada, Hoy created an extraordinary record of his multiracial community.

Born in Guangdong, China, Hoy came from a family of limited means. His father borrowed funds to pay the Canadian government’s head tax levied against Chinese people from 1885 to 1923, enabling Hoy to immigrate. After he arrived in Vancouver in 1902, Hoy worked a variety of jobs, including as a cook and gold miner. He learned photography in the town of Barkerville in British Columbia’s Interior, but most of Hoy’s portraits were made in Quesnel, after he bought a general store and set up a studio as part of the business.

Between 1909 and 1920, Hoy photographed a broad cross-section of residents in the Cariboo region. For Chinese workers, especially miners, he produced elegant and creatively staged portraits they could send back to family abroad. Hoy mixed Chinese portrait conventions, such as the full-frontal pose of many of his sitters, as can be seen in Elaine Charleyboy and Chief William Charleyboy (Redstone), c.1910, with the Western use of backdrops and props. Hoy’s archive includes a significant number of photographs of Indigenous subjects (including Carrier and Tsilhqot’in people) as well as white settlers. Lacking expensive lighting equipment and interior space, Hoy made many photographs outside, especially for large groups and during events such as Quesnel’s annual Dominion Day Stampede, which drew visitors from far and wide.

Hoy’s negatives were acquired by the town of Barkerville from his family. As photographs specifically commissioned by individual sitters, Hoy’s work showcases a unique archive of frontier life that is quite different from ethnographic and government archives.

About the Authors

About the Authors

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements