From museums, government, and corporate archives to illustrated magazines, artist-run organizations, and educational settings, institutions shape how we see, value, and understand photography in Canada. But many social, political, and economic factors also influence who becomes a photographer, what gets photographed, and whose work is published and exhibited. Any history of photography should consider how photographers learn their craft, choose their subjects, and show their work. Many of the institutions discussed here are transnational; they are large and small, formal and informal, but they all influenced the development of photography in distinctive and important ways.

1840s–1880s: Building a Professional Foundation

As soon as Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (1787–1851) announced the daguerreotype process in 1839, writers and editors of newspapers and scientific journals were eager to spread information about photography. Only a decade later, photo-specific journals began to appear in Europe, the United Kingdom, and the United States—and reached many avid readers and contributors in Canada. Initially, these publications were directed at professional photographers and scientifically inclined amateurs. Often they reprinted articles from newspapers and other journals to keep readers abreast of the latest techniques and do-it-yourself formulas, provided sources for ordering materials and equipment, and offered examples of innovative business models. These journals would go on to publish texts submitted by practitioners as well as scientists and suppliers, who all had a stake in the development of the photographic arts.

At this time, safety was a major issue for the nascent profession that crossed national borders, and the journals were an important source of information for photographers. In 1852, an issue of the Photographic Art Journal noted that a New York daguerreotypist named Jeremiah Gurney was so unwell from mercury poisoning that his life was in danger. The editor noted that this was the fourth such incident they had heard of in two years and that it was crucial for photographers to be familiar with potential risks and to know how to mitigate possible dangers.

Journal editors were also some of the earliest arbiters of photographic quality and professionalism, as they decided whose work to feature and what issues in the field were worthy of debate. William Notman (1826–1891), a canny studio owner, advertised in a range of publications and forged a close friendship with Edward L. Wilson, founder and editor of The Philadelphia Photographer, who regularly praised and promoted Notman’s work in print. Wilson’s journal was also one of the first to circulate photographic prints before they could be integrated into the text, and he featured the work of Montreal photographer James Inglis (1835–1904) three times in the late 1860s. In a playful image designed to appeal to his fellow photographers, Inglis positions a jovial baby as the camera operator surrounded by the props and headrests of studio work.

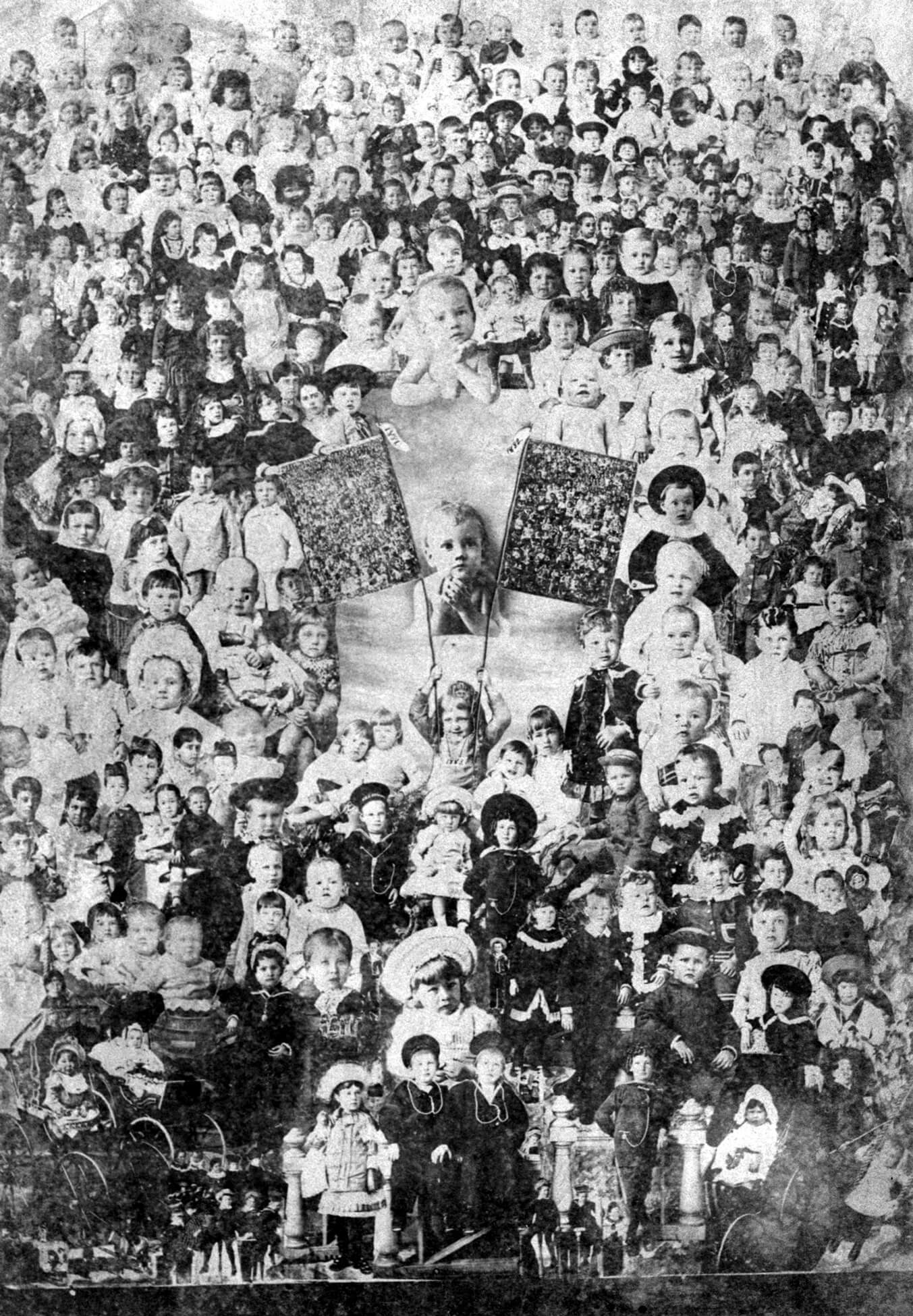

Journals also showcased innovative commercial ventures. In the late 1880s, Hannah Maynard (1834–1918) wrote letters and regularly sent examples of her “Gems,” her studio shots of children, to the St. Louis and Canadian Photographer, run by Mrs. Fitzgibbon-Clark. This journal celebrated Maynard’s “beautiful” and “increasing family” of children’s photographs, approving of both the photos and what was deemed Maynard’s appropriately feminine focus.

Although there were sporadic efforts to establish Canadian photography journals in the nineteenth century, they never achieved the number of subscriptions necessary to survive. The Canadian Photographer lasted just a few issues in the late 1880s before it was incorporated into the St. Louis Photographer.

Even after Confederation, in 1867, the development of professional photographic communities in Canada tended to be regional rather than national. Transcripts from the fifth annual meeting of the American National Photographic Society in Buffalo, in 1873, indicate that several Canadians were members and attended. In 1889, Anthony’s Photographic Bulletin (New York), which included lists of amateur and professional photographic societies, recorded Canadian photography groups alongside American ones. Photographic societies of the British Isles and British colonies were listed separately. Although Canada and Australia were still British colonies at the time, the transnational development of North American photography eclipsed political accuracy. Even though these early journals and associations were located outside of the shifting boundaries of nineteenth-century Canada, they provided crucial opportunities for Canadian photographers to hone their craft and build community.

1850s–1890s: The Rise of Exhibition Venues

Until the arrival of halftone printing at the end of the nineteenth century, the only way to publish photographs together with text was through engravings made after photographs or through the expensive process of pasting in photographic prints. As a result, proponents of the early print culture of photography directed readers to galleries and venues where they could see photographs firsthand. The first mention of a Canadian exhibition venue shows up in the New York–based Photographic Art Journal in October 1851, only a few months after the journal’s first issue. The announcement read that “[Donald] McDonell, of Buffalo, has established a gallery in Toronto… where he is teaching the people to appreciate fine specimens of his art.”

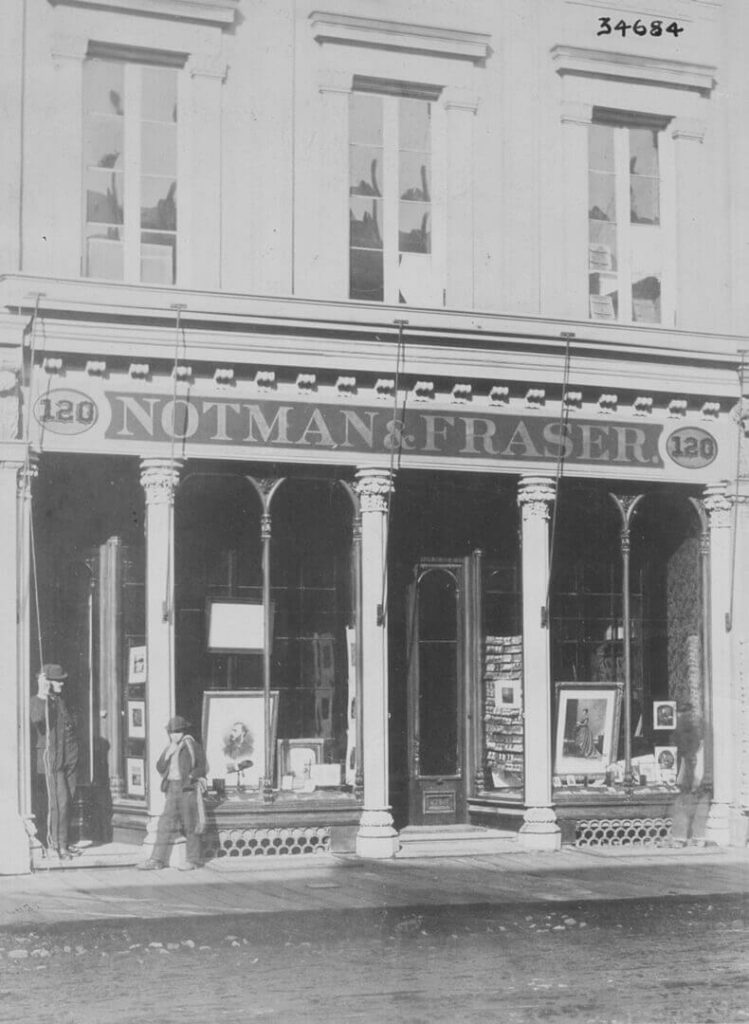

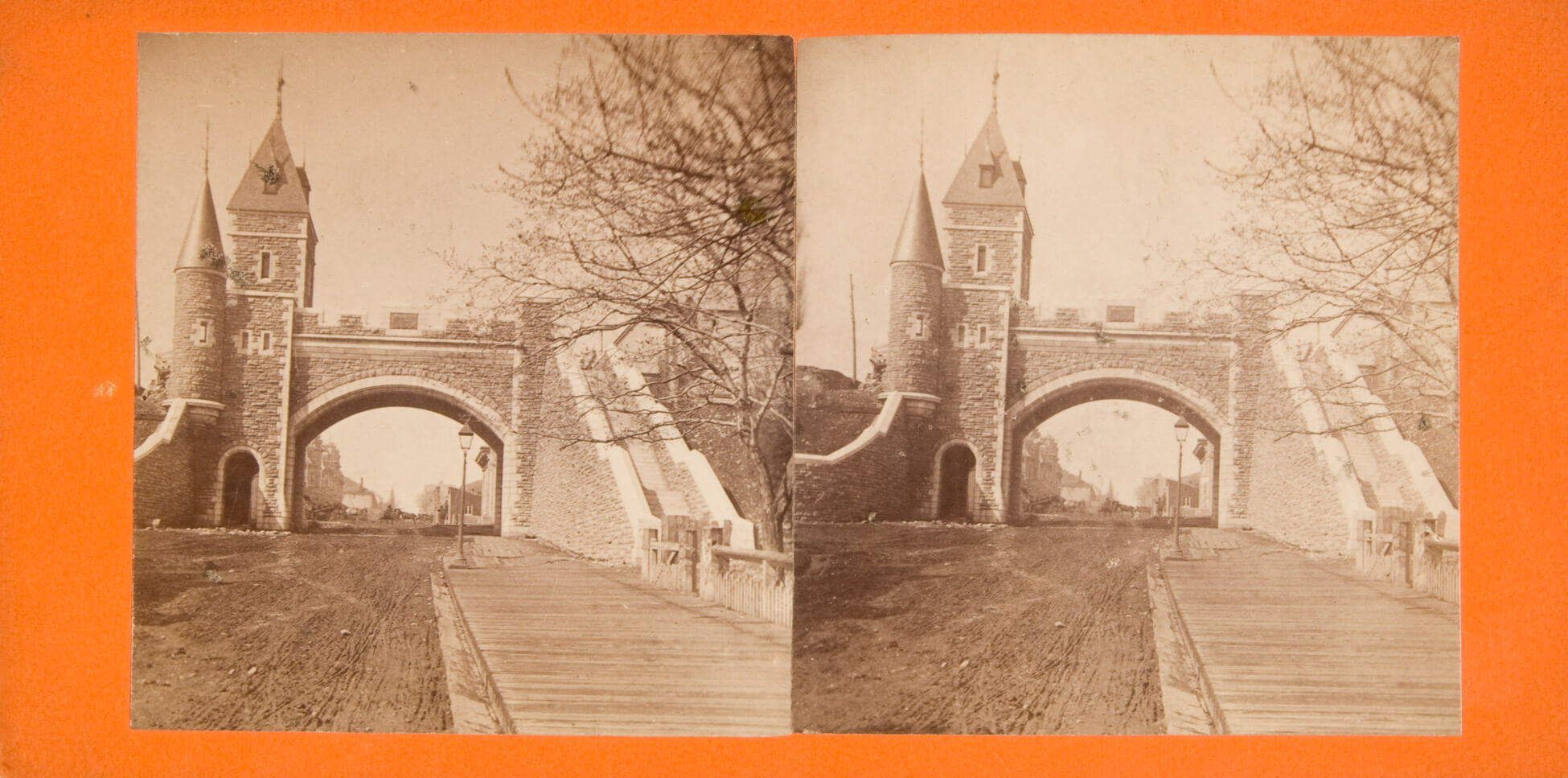

The owners of commercial studios, such as William Notman, not only generated the majority of photographs, sold equipment, and provided instruction, but their studios also served as important exhibition spaces on the street and in the interior reception spaces. A photograph of the Notman & Fraser premises shows a myriad of samples of the studio’s work displayed in frames and albums. And as these entrepreneurs drummed up business, they were also helping to guide the public’s taste and appreciation of this new art form. Photographers placed ads in newspapers encouraging readers to stop by and peruse the samples of a studio’s work and the stock images they had for sale. Flattering portraits of well-known figures in storefronts and reception rooms demonstrated both the photographer’s skills and prestige to clients and served as a steady form of income for the studio. Interspersed in studio displays were other photographs, mainly landscape or wildlife images either in the form of postcards or stereographs. These photographs were especially popular with tourists and visitors, so studios kept a supply on hand. While larger studios such as those run by George William Ellisson (1827–c.1879) and Louis-Prudent Vallée (1837–1905) made their own stereo views, most smaller studios sold views made by other photographers.

In the United States and Europe, photographic exhibitions were integrated into world’s fairs and industrial exhibitions beginning in the 1850s. Photographers based in the colonies were typically a small segment of these events, but their landscape views provided crucial visual evidence of the European imperial expansion these events sought to celebrate. At a Dublin exhibition in 1865, a submission of photographs by the Quebec Board of Works won an honourable mention alongside Notman and Alexander Henderson (1831–1913). Although these fairs were temporary, they were well attended and diligently covered by the daily press and photographic journals. Photographers who won prizes at these events increased both their profile and the appetite for their work with locals and visitors. Jules-Isaïe Benoît Livernois (1830–1865) of the Livernois Studio (1854–1979) also submitted a collection of Quebec views to the same exhibition.

The cost of showing work at international exhibitions was beyond the reach of most early photographers, but some Canadians regularly sent submissions to these large fairs. Notman won a gold medal for “excellence in an extensive series of photographs” at the London International Exhibition of 1862, a massive demonstration of the fruits of the Industrial Revolution organized by the Society of Arts, Manufactures and Trade. Francis Claudet (1837–1906), who was living in British Columbia at that time, also received an honourable mention, for his views of New Westminster. Claudet was an accomplished amateur photographer—a practice he learned from his father, Antoine, a professional daguerreotypist who served on the jury for the exhibition.

As the economy in Canada grew, so did local fairs. The Livernois family’s studio exhibited several photographs in the 1871 Quebec Provincial Exhibition, and Vallée drew attention to his contributions in an advertisement in the bilingual guide for visitors. In 1890, Regina’s newspaper the Leader celebrated an exhibition of over fifty prints by studio photographer W.F.B. Jackson at the Seventh Exhibition of the Assiniboia Agricultural Society. Jackson’s focus was portraiture and the newspaper listed the local luminaries whose photographs he put on display at the fair alongside exhibitions of quilts and Indigenous crafts.

Early public exhibitions in studios and at fairs offered a wide range of photographs to viewers and served as a form of both entertainment and edification. As more exhibition venues emerged in the coming years, their role in cultivating interest in making and collecting photographs expanded.

1890s–1970s: Camera Clubs and Communities of Practice

The advent of the snapshot camera dramatically shifted the structure of photographic communities and led to a burst of amateur activity across Canada. The most popular of these cameras was the Kodak, released by George Eastman in 1888. This camera was simple, and reflecting the attitudes of the time, Kodak’s ads promised “even women and children could use it.” Although earlier professional networks had emerged through commercial studios, aided by newspapers and journals, the arrival of the new cameras prompted professional photographers and the serious amateurs who wanted to distinguish themselves from those taking casual snapshots to refine the practice of photography through the creation of camera clubs.

In the early twentieth century, camera clubs were common in urban centres. They were modelled on amateur photographic societies in the United States and the United Kingdom and quickly became key sites where enthusiasts could gather to study and share their interest in photography. The first clubs in Canada included the Quebec Amateur Photographers’ Association (1884–86), the Quebec Camera Club (1887–96), and the Montreal Camera Club (established 1890). In Ontario, the Toronto organization was founded in 1887 and changed names twice before settling on the Toronto Camera Club in 1891. Not long after, camera clubs were also formed in Hamilton and Ottawa. Although the Ontario and Montreal clubs are still in operation, many early clubs are not, including those in Winnipeg, Saint John, Halifax, and Vancouver, making it hard for scholars to capture the full spectrum of their activities because the records no longer exist or are not accessible.

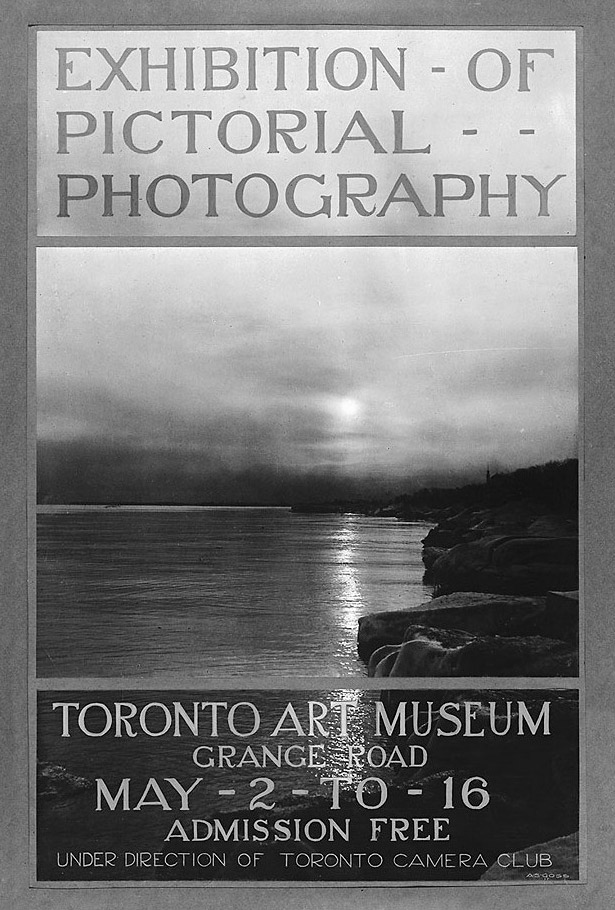

With few options available for formal training in Canada, camera clubs played a major role in photographic study, experimentation, and networking, and they provided spaces where members could discuss each other’s prints. Monthly critiques played an important role in the technical and stylistic development of club members. In the smaller clubs, photographers were often assigned a single subject matter or genre to produce work for evaluation. But in the larger organizations, such as the Toronto Camera Club, members could submit their work under traditional exhibition categories, such as portraiture, genre, still life, architecture, landscape and marine, natural history and scientific, as well as special topics, with awards given to members for the best work. For instance, Arthur Goss (1881–1940) won a bronze medal in the landscape category for his photograph The Bluffs, c.1918. Larger clubs also often facilitated lectures, organized group outings to local vistas, and provided access to equipment, darkrooms, enlarging and printing rooms, studio space, and photography reference books and periodicals.

Camera clubs were not just instructional; they were also social. Through these clubs, amateur photographers could learn from professionals, members could expand their networks, and all could keep an eye on emerging trends and styles. The members often represented the social networks of the time and occasionally functioned as an indication of socio-economic class. The clubs in Quebec were almost entirely made up of English-speaking members, perhaps due to the propensity for English Canadians to form clubs in general, but also because of differences in religion, socio-economic background, and education. Similarly, Japanese Canadian photographers and enthusiasts founded a camera club in Vancouver, likely because they were not welcome in the ones founded by white settlers in that time.

Women were accepted in photography clubs from the beginning and were often awarded prizes at club competitions, and sometimes made appearances on the executive committees. However, the rising professionalism in the field would limit and shape women’s roles. The membership of women was not without controversy, and they were not always afforded full member benefits. The Toronto Camera Club, for example, included women as full members in its 1889 constitution, but continuously debated women’s membership status until 1942, when women were finally confirmed as active members with the same privileges as men.

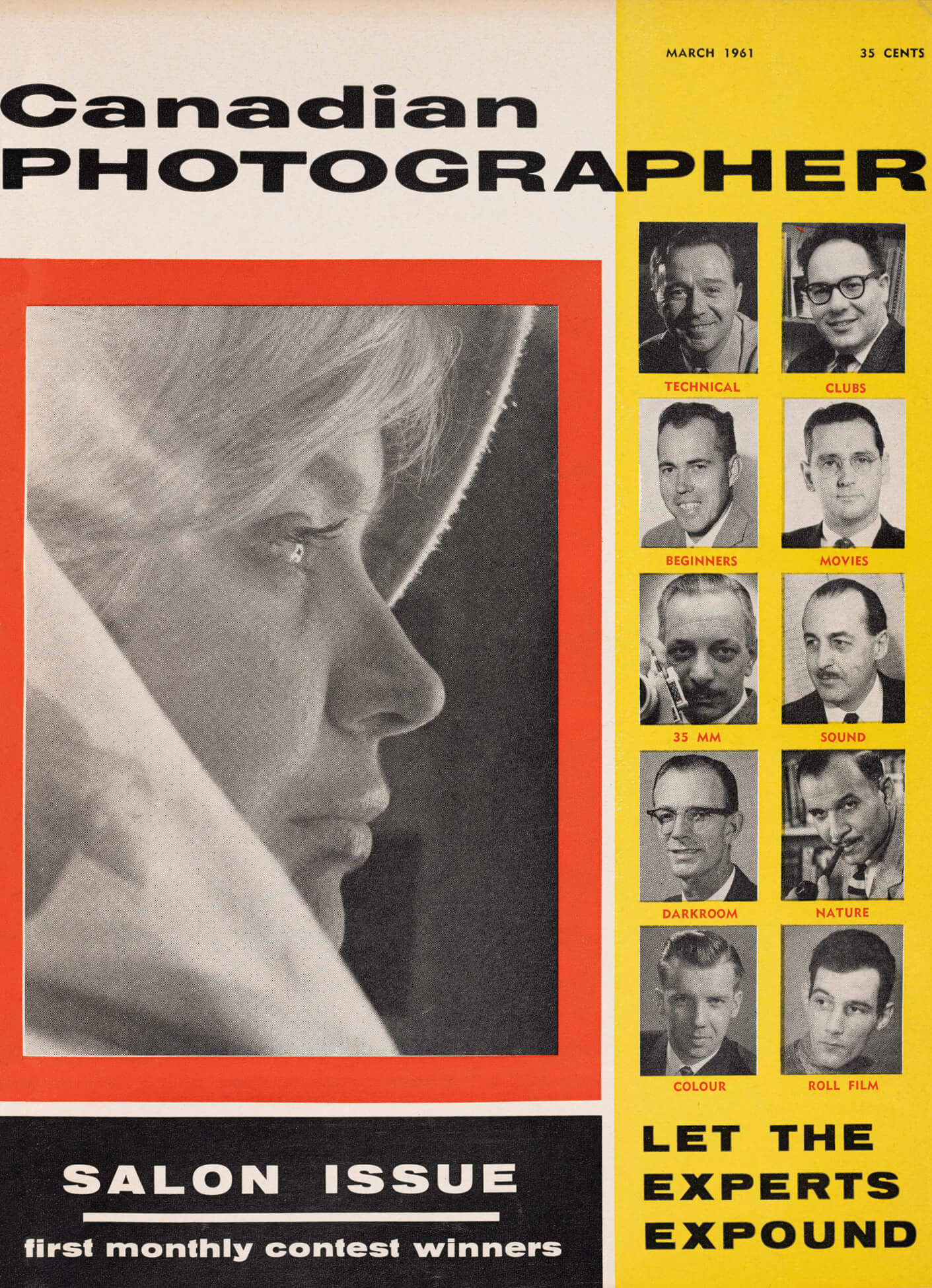

Although local photography clubs continued to operate after the Second World War, popular magazines like the Canadian Photographer offered instruction and community for a wide range of aspiring photographers, from amateur wildlife enthusiasts to commercial practitioners. Alongside ads for camera equipment, the magazine conveyed rules for best practices, celebrated technical skill over experimentation, and offered monthly illustrated how-to guides for photographing subjects such as sailboats, the Rockies (even through a car, train, or plane window), kittens, and children. The practical advice, reviews of equipment, and exemplary images in Canadian Photographer reflected the interests and work of both amateurs and commercial photographers, particularly those in advertising and portraiture.

Hints of more experimental approaches are evident in this magazine, but these were often made in the context of how to “tastefully” photograph the female nude, such as through non-transparent glass. The magazine’s cover from March 1961 lays bare the stark gender and racial politics. On the left is an artistically lit photograph of a woman’s face and on the right are headshots of ten men, the photographic experts who “expound” in this issue. In this configuration, women’s bodies are normalized as subjects for men to look at and photograph—and these men are almost exclusively white, and their views are elevated and justified as those of the expert or connoisseur. This organization of photographic power not only reflects amateur photography circles or popular culture, but also the norm across all areas of photographic practice from commercial to artistic, a fact that would galvanize the social upheavals of the 1960s.

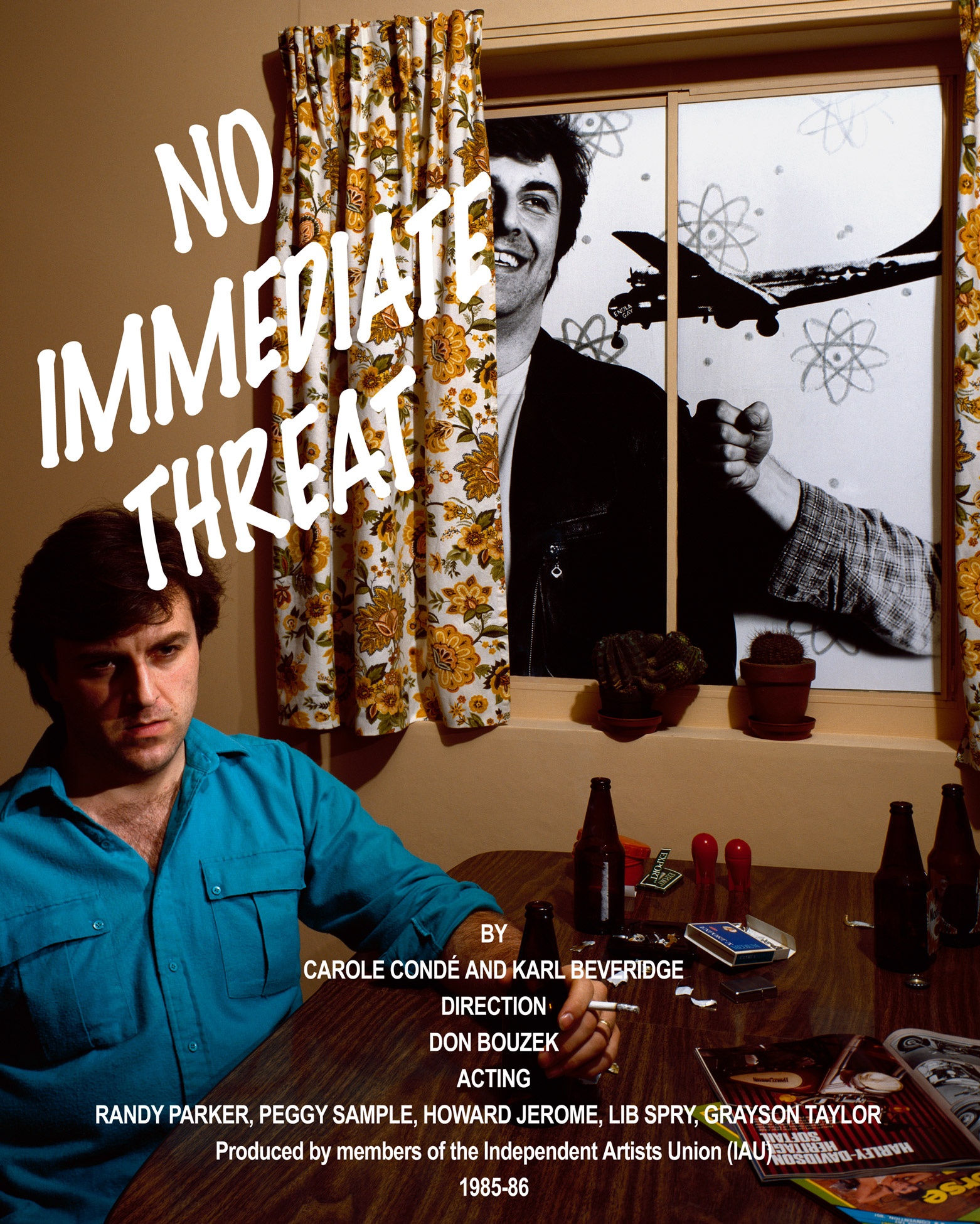

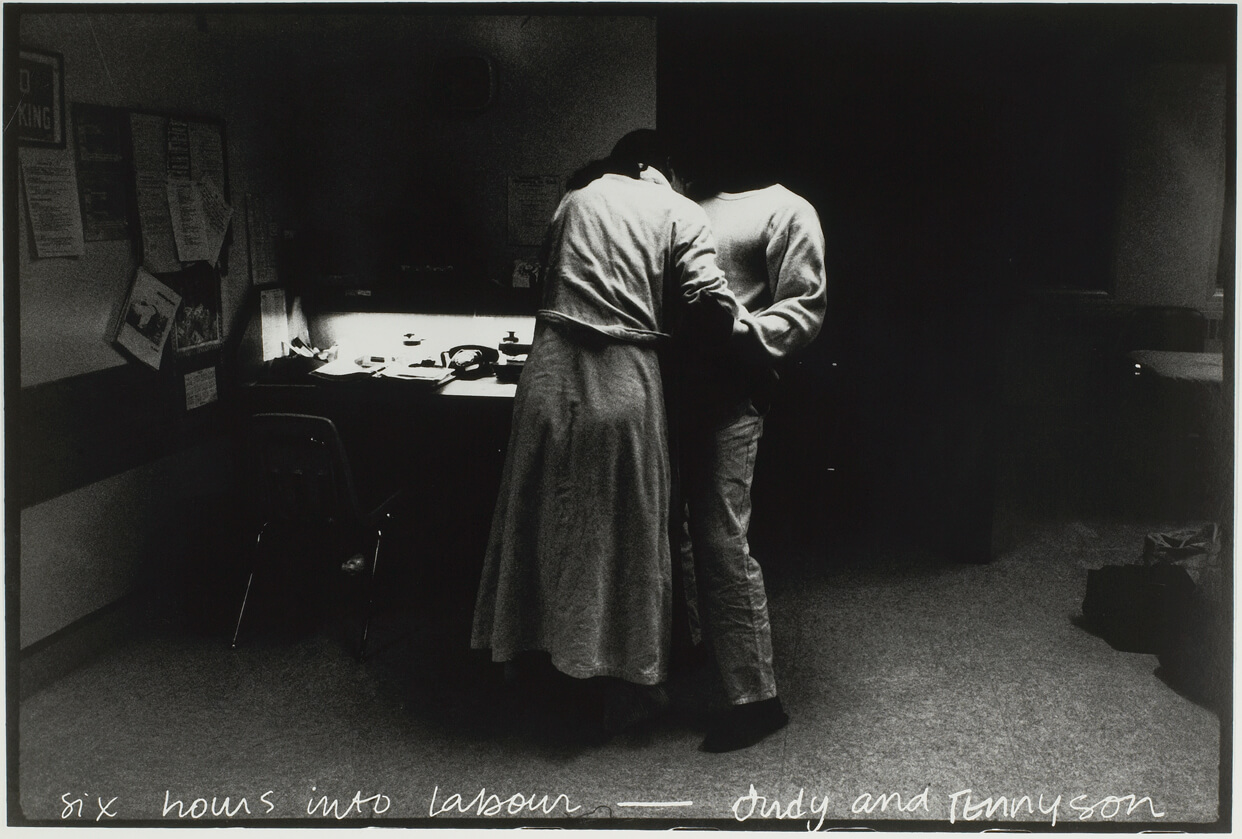

With the integration of photography into the field of contemporary art and a turn to socially engaged practice, photographers including Claire Beaugrand-Champagne (b.1948), Carole Condé (b.1940) and Karl Beveridge (b.1945), Angela Grauerholz (b.1952), and many others formed communities and networks not through clubs but around galleries, art schools, and later artist-run institutions and publications.

1890s–1950s: Exhibitions as Spaces of International Exchange

From their earliest days, competitive exhibitions sponsored by large camera clubs provided members with the opportunity to gain public acclaim and prizes, including club medals or equipment donated by photo supply dealers. These competitions also familiarized members with the work of national and international amateur and professional photographers. When Mathilde Weil (1872–1942) of Philadelphia won both a gold and a bronze medal at the 1898 Toronto exhibition, it made headline news in the Toronto Mail: “Lady Takes First Place. Miss Weil’s Success at the Camera Club’s Exhibition.” To make the most of these competitions, participants often submitted prints to various exhibitions. For instance, Sidney Carter (1880–1956) submitted his Pictorialist work Evening Sunset on Black Creek, c.1900–01, to multiple venues; it was exhibited at the Philadelphia Salon in 1901 and was awarded the members’ gold medal at the 1902 Toronto Camera Club exhibition.

Exhibitions were an important way for camera clubs to forge connections between photographic communities. The Toronto Camera Club’s first International Salon in 1903, coordinated by Carter, was instrumental in exposing the public to eminent Pictorialists like Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946), who sent thirty prints from the loan collection of the Photo-Secession, an organization based in New York.

A photograph from 1927 shows jurors of an International Pictorial Photographic Salon held on the West Coast, including New Westminster–based H.G. Cox (1885–1972), John Vanderpant (1884–1939) of Vancouver, Victoria studio photographer Harry Knight (1873–1973), and Dr. Kyo Koike (1878–1947), one of the founders of the Seattle Camera Club, just across the border.

Camera club exhibitions in the 1930s laid the groundwork for the first museum exhibitions of photography in Canada. Following his Pictorialist-heavy exhibition for the Toronto Camera Club, Carter curated the first Pictorialist exhibition at the Art Association of Montreal (now the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts) in 1907, showing works by Harold Mortimer-Lamb (1872–1970) and Arthur Goss among others. By the 1940s, the photography exhibitions at the association were organized by the Montreal Camera Club.

In conjunction with the Ottawa Camera Club, the National Gallery of Canada (NGC) hosted the Canadian International Salon of Photographic Art from 1934 to 1939. Curator Andrea Kunard notes that National Gallery funding for touring exhibitions meant that “photographs by camera club members could be seen at the Winnipeg Art Gallery, the Vancouver Art Gallery, the Edmonton Museum of Fine Arts, as well as other venues.” Kunard also points out that photography was appealing to the NGC because all the institutions were labouring under budget cuts, and photography was simply less expensive to prepare, ship, and exhibit than other art forms.

In the early part of the twentieth century, the eclectic group of photography exhibitions included those held in salons, commercial galleries, and photo studios. This last category included smaller rural studios like that of C.D. Hoy (1883–1973), located in his general store in the Cariboo region of British Columbia, where the samples of his work would have been found beside postcards and other goods for sale. These scattered early exhibitions rarely generated prominence for individual photographers or a clear direction for photography, but they did help to foster critical discussion and wider interest.

In the 1930s, museums across Canada began to curate solo exhibitions of work by select photographers. The Vancouver Art Gallery’s 1932 exhibition of Vanderpant’s work was a serious boost to his career. In 1935, the Art Gallery of Ontario held a memorial exhibition of work by M.O. Hammond (1876–1934), followed by an exhibition of plant studies by E. Haanel Cassidy (1903–1980) in 1938.

1951: Public Funding for Photography

After the Second World War, the Canadian government initiated a Royal Commission on National Development in the Arts, Letters, and Sciences (also known as the Massey Commission) in an effort to produce a coherent government policy for the arts and culture sector. The resulting Massey Report of 1951 offered an extensive analysis of Canada’s cultural life, along with a set of recommendations, and this led to an exponential increase in funding and opportunities for photography in Canada. The establishment of the Canada Council for the Arts in 1957 provided funding to artists, arts publishers, artist-run centres, and galleries and museums to facilitate travelling exhibitions across the country. The report also celebrated and called for increased support of more directly nationalistic endeavours, such as the photographic work of the National Film Board (NFB).

Although government agencies had been commissioning, collecting, and using photography since the mid-nineteenth century, the establishment of the Still Photography Division (SPD) at the NFB in the early days of the Second World War marked a decisive new chapter for photography and nationalism in Canada. Led by a Scot named John Grierson, who coined the term “documentary,” this division produced an abundance of material, including photo stories, exhibitions, and catalogues.

The day-to-day work of the SPD in the 1950s is described as “banal nationalism.” With stories like “Canada’s Scientists Get Behind the Serviceman” (1955, Chris Lund and Herb Taylor) and “English Lessons with Leah” (1958, Ted Grant), viewers were encouraged to reflect on the development of Canada through topics such as industry and labour, natural resources, and profiles of different cultural groups. But the SPD also helped to define postwar photography through its robust publications and regular exhibition programming at its dedicated gallery space in Ottawa. These often featured more artistic and experimental work, either by one photographer, such as Lutz Dille (1922–2008), or by bringing together images around a theme such as The Female Eye (1975).

The 1950s and 1960s represented the heyday of illustrated picture magazines in Canada before TV captured the attention of the public. In 1960, the Star Weekly, “Canada’s largest separately sold periodical,” hit a circulation of 1 million. At the same time, 1.5 million copies of the Weekend magazine were printed each week and circulated as an insert in twenty-five daily newspapers. But the editors of these publications were not risk-takers. They were looking for striking images that would engage readers without alienating advertisers. In 1964, the Star Weekly commissioned Michel Lambeth (1923–1977) to create a photographic series about the poverty-stricken residents of St. Nil, Quebec. When his images were rejected for being too demoralizing, the NFB purchased the negatives and circulated images in exhibitions and publications.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the SPD was directed by Lorraine Monk, who shifted away from employing staff photographers who were producing documentary photo stories to hiring younger freelancers working in more expressive styles, such as Lambeth, Pierre Gaudard (1927–2010), Nina Raginsky (b.1941), and Michael Semak (1934–2020). However, as Carol Payne has noted, the change in style did not completely push aside the division’s nationalist mission. At Monk’s request, the division received a significant allocation from the federal government to produce a 1967 centennial book and exhibition project, Canada: A Year of the Land, which included photographs by Roloff Beny (1924–1984) and John de Visser (1930–2022). According to Payne, the aestheticized landscape photographs included in the book and exhibition of an “evacuated land, idealized the nation, and erased Aboriginal presence.”

Many of the photographers who worked for the NFB during this time also freelanced for major newspapers and periodicals. Krijn Taconis (1918–1979) was a member of the influential Magnum collective of photojournalists before he moved to Canada. He continued to take on international assignments even as he shifted to work more extensively with the NFB. In 1969, the NFB published a book of Michael Semak’s photographs of the newly independent country of Ghana. These photographers brought the world to Canadian viewers and represented Canada to the world.

Through their commissions, the mainstream press and the NFB played a role in nurturing and shaping the format of photojournalism as it developed in tandem with more experimental artistic documentary photography. The efforts of the NFB in particular were successful in adding contemporary photography to growing national collections because they retained all the work they commissioned.

1960s: The Race to Build Museum Collections

In the 1960s, Canadian museums, like those around the world, began collecting photography in earnest, a move driven by what former National Gallery of Canada (NGC) director Marc Mayer described as “an appreciation of photography’s archival significance and its role in the evolution of modern art.” Canada already had a national photography collection in Ottawa. Since its founding in 1872, Library and Archives Canada (LAC) has collected 30 million photographs as part of its mandate “to preserve the documentary heritage of Canada for the benefit of present and future generations.” Since much of this collection was created through government projects, such as the geological surveys Charles Horetzky worked for, the resulting research often focused on photography and nation building, which has advanced conventional settler-colonial narratives.

In 1967 and at the request of NGC director Jean Sutherland Boggs, curator James Borcoman initiated the gallery’s photography collection. Borcoman’s annual budget was a modest $5,000, but given that the robust market for photography was still a few years away, he had a reasonable start, especially with the support and guidance of a range of international experts. By 1974, the NGC’s photography collection contained 6,000 images, which were mostly historical and which included many by canonical international figures like William Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877), who developed one of the first photographic processes. As prices for photographs increased, subsequent acquisitions by Borcoman focused on modernist and more contemporary work that was purchased or acquired through private donations.

What the NGC chose to collect through purchases and gifts shaped the kind of exhibitions it could mount and the work it could make available to artists and photographers for study. Initially, Borcoman focused on acquiring the work of European and American photographers, such as the abstract photos of Man Ray (1890–1976) purchased in 1968, in part because of the NGC’s desire to acquire canonical images valued for their aesthetic qualities, but also to avoid duplicating the historical Canadian collections held by the national archives and the contemporary work located in the NFB Still Photography Division. But in 1960, and again in 1988, the NGC mounted major exhibitions of portraits by Yousuf Karsh (1908–2002), even though his work was often government-commissioned. Then, in the 1970s, the NGC acquired the collection of Canadian photography belonging to amateur historian Ralph Greenhill and received important donations from architect Phyllis Lambert and others.

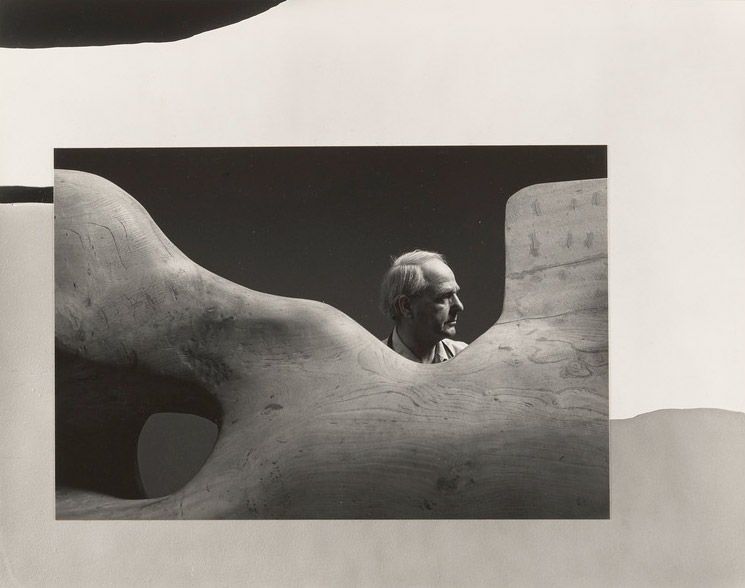

Borcoman’s approach to collecting photography for the NGC was in contrast to the way curator Maia-Mari Sutnik built the collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO). Sutnik had a later start than Borcoman and was faced with a limited budget and a small core collection of photographic portraits of artists, so she focused on photography as a form of material culture and primarily acquired photographs made for commercial, scientific, personal, and governmental purposes. She also made strategic purchases, such as the collage portrait by Arnold Newman (1918–2006) of sculptor Henry Moore (1898–1986) to augment the gallery’s collection of Moore’s work.

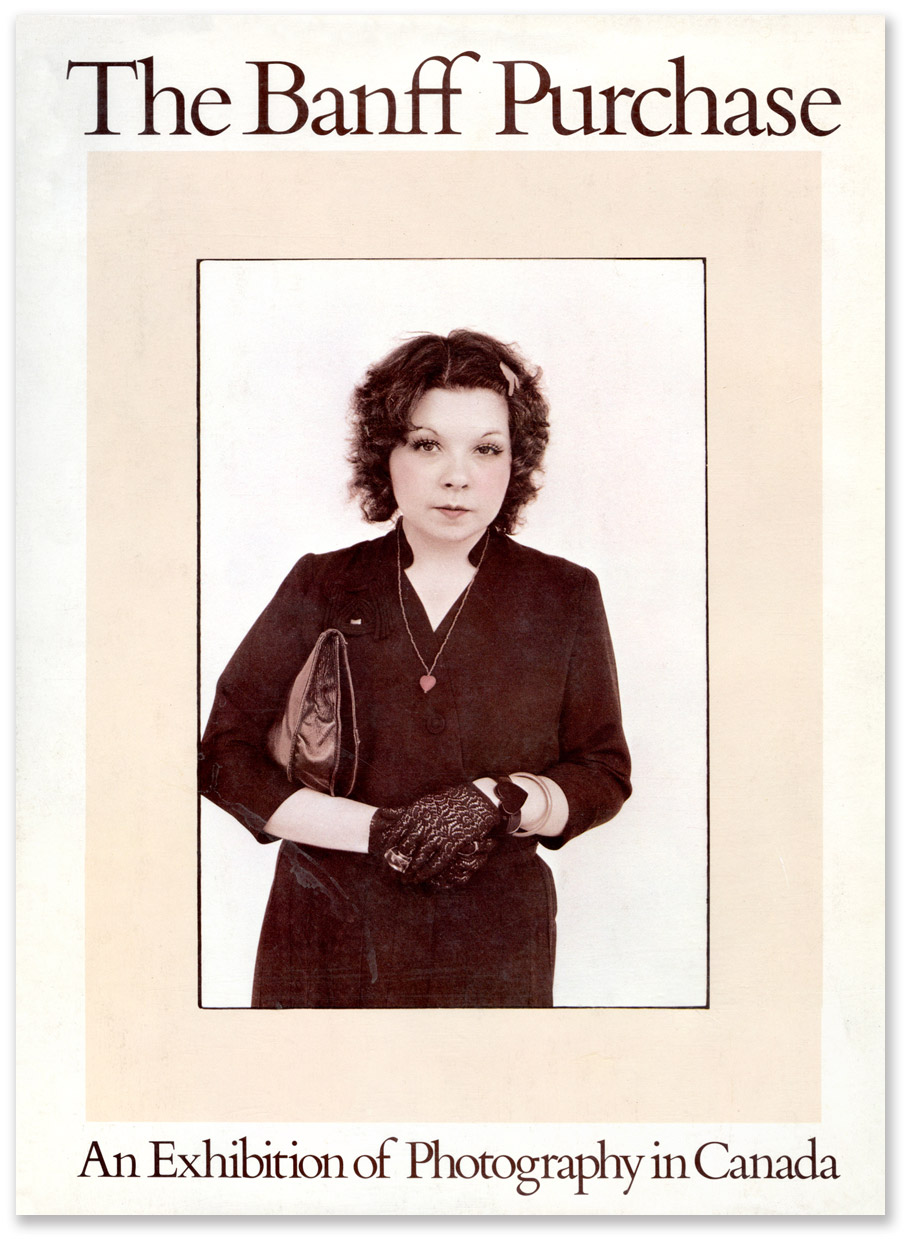

In 1979, curators Hubert Hohn and Lorne Falk took a different approach to building a core institutional collection for the Walter Phillips Gallery. Instead of collecting works by established photographers, they made a high-profile purchase of work from seven contemporary artists for the gallery located in the Banff School of Fine Arts. That purchase, along with its travelling exhibition and publication, highlighted the quality of work produced in Canada by individuals such as Lynne Cohen (1944–2014), Nina Raginsky, Orest Semchishen (b.1932), Tom Gibson (1930–2021), and Charles Gagnon (1934–2003).

That same year, Andrew Birrell, head of acquisitions at Library and Archives Canada, announced a new initiative to diversify his institution’s photography collection by collecting the work of a wider range of amateur photographers to complement “the work of professionals who usually photographed only what would sell or what they were paid for.”

Another initiative, Project Naming, did not add new photographs but instead added new information and a distinctly different perspective to the historical photographs in the LAC collection. This community collaboration was initiated outside of the LAC in 2001 with Nunavut Sivuniksavut, a post-secondary program for Inuit youth based in Ottawa, and with Morley Hanson (Nunavut Sivuniksavut coordinator) and Murray Angus (instructor). During the first phase of the project, Inuit students interviewed Elders in their home communities to learn the names and familial relationships of people portrayed in photographs from the mid-twentieth century by Richard Harrington (1911–2005). Working with 500 digitized images taken in four Nunavut communities, Elders identified 75 per cent of the people in the images. For instance, Gar Lunney took a photograph of three Inuit men in traditional dress holding cameras before Canada’s Governor General, Vincent Massey, arrived on his northern tour of 1956. The original caption framed the image as an ethnographic document, but understanding that one of these men was the renowned hunter and community leader named Joseph Idlout recasts the image as a document of diplomacy.

The interview process used in Project Naming reinforced Inuit cultural values and was a means of addressing the cultural dislocation that has resulted from colonization. The project continues virtually on LAC’s website with approximately 10,000 digitized images, and over the years, community members have identified several thousand people, activities, and places. Described in the scholarship as a form of visual repatriation, Project Naming inverts the power dynamic of a colonial government archive by returning agency to the Indigenous people of Nunavut.

At each of these major institutions, it is often the long-serving staff who have exerted considerable influence over the collecting practices, new initiatives, and curatorial directions. When the Still Photography Division at the NFB was under Lorraine Monk’s leadership, the institution’s collecting practices expanded beyond the negatives and transparencies created by staff photographers to establishing a fine print collection.

In the centennial year of 1967, the NFB inaugurated an exhibition space, the Photo Gallery in Ottawa, and expanded their publication activities with the Images book series, featuring projects by Lutz Dille, Pierre Gaudard, Judith Eglington (b.1945), and Michael Semak, as well as the BC Almanac(h) C-B, an anthology of artist booklets and an exhibition created by Jack Dale and Michael de Courcy (b.1944) in 1970. The NFB’s fine print collection also formed the core collection of the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography, which was established in 1985 and helmed by Martha Langford. Under her tenure, the museum pursued an ambitious exhibition and publication program. It closed in 2006 after suffering water damage, and in 2016, the collection of over 200,000 photographs was transferred to the NGC.

In addition to national institutions, numerous community archives have contributed to the history of photography in Canada through the preservation and interpretation of local and regional histories, including some lesser known and marginalized stories. The holdings of the Cumberland Museum and Archives, for example, include the photographs of Hayashi Studio. Senjiro Hayashi (1880–1935) documented the thriving Japanese community, Chinatown, local coal mines and sawmills, and other aspects of early twentieth-century life on Vancouver Island. With the donation of this collection of hundreds of glass negatives in the 1980s, often-overlooked histories were revived through an exhibition and documentary film. The community-organized Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia collects visual documents of the rich history of Black residents. The Centre’s 1983 exhibition A Black Community Album Before 1930, brought together snapshots of church groups, labourers, and families as well as commercial portraits of children, students, soldiers, and other Black professionals.

1960s–1980s: Galleries, Publications, and Associations

Although support from the Canada Council allowed large institutions to circulate exhibitions, it was new funding and initiatives at both the federal and provincial levels that radically changed how artists worked. Not only did the Council offer funding directly to photographers to undertake substantive projects and to travel, but funding also became available for a range of artist-run centres, associations, and publications. Often, these activities were connected and overlapping, offering artists more control over the production and circulation of their work.

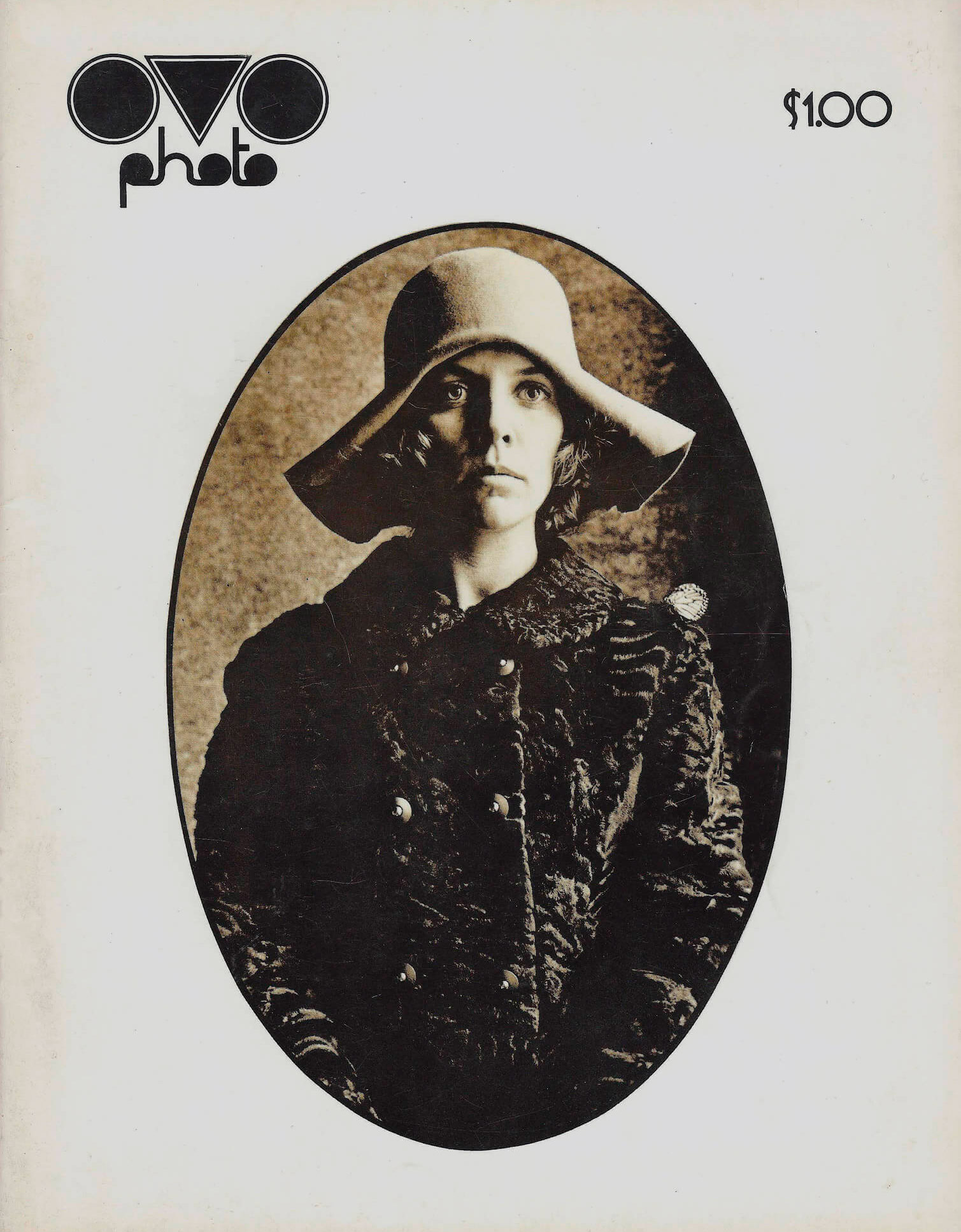

From the early 1970s a number of publications sought to share work and connect artists across the country. Many were short lived or sporadic, reflecting the challenges of collaborative projects in a new format. However, publications such as Impressions and Image Nation, published out of Toronto, and OVO Photo, in Montreal, managed to share new work created across the country and they did so without having to rely on the cycle of curated exhibitions and critical reviews. And experimental initiatives, such as Image Bank, an artistic collaboration between Michael Morris (b.1942), Vincent Trasov (b.1947), and, until 1972, Gary Lee-Nova, explored new modes of networking, such as mail art, as an alternative to the gallery system.

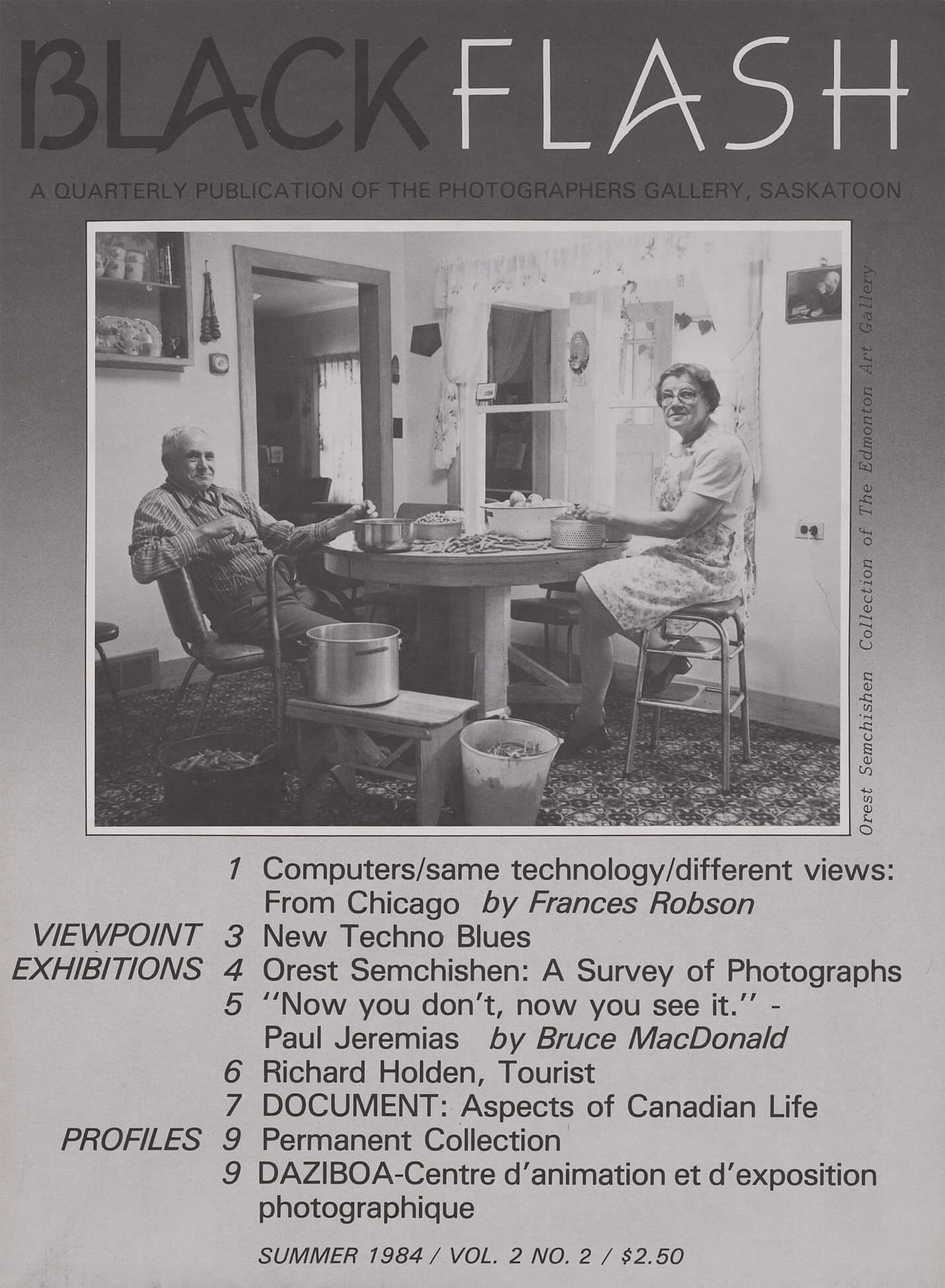

As art historian Johanne Sloan has observed, artist-run centres across the country gave loosely organized networks access to facilities, exhibitions, events, and publications. For instance, the Photographers Gallery in Saskatoon originated in 1970 with a collective of photographers who wanted to share resources and expertise including a darkroom and library. By 1973, the group had formed a gallery with an exhibition program before beginning to collect photography in 1977 with an acquisition of a work by Mattie Gunterman (1872–1945). In 1983, the gallery started a magazine that soon became BlackFlash, one of the longest running photo and new media publications in Canada.

In 1977, the collective of fifty artists who founded the Toronto Photographers Workshop (TPW) addressed the lack of support for photography as a contemporary art form by providing designated exhibition space and a forum for lectures and discussions, and by commissioning texts about contemporary photography and photographers from art critics and curators. Suzy Lake (b.1947), Barbara Astman (b.1950), Condé and Beveridge, Edward Burtynsky (b.1955), and Robert Burley (b.1957) were all active at TPW.

Artists were also the force behind Gallery 44, a collective formed in 1979 to share production facilities including a darkroom and studio space. This made the necessary technology available to more photographers and created another community hub. Soon, Gallery 44 was mounting exhibitions and offering photography workshops for artists and youth.

In Montreal in the late 1980s, a significant number of feminist artists and photographers, including Raymonde April (b.1953), Geneviève Cadieux (b.1955), Sorel Cohen (b.1936), and Angela Grauerholz (b.1952), were experimenting in various ways with postmodernism, mixing photography and other media. Feminist initiatives at artist-run centres such as Optica, Dazibao, and VOX also brought Canadian artists into contact with sympathetic international practitioners and critics. Although these initiatives were successful individually, the Montreal network of feminist photo-centric artists never received the same level of institutional, curatorial, or critical support and international reification as the Vancouver “boys’ club” of photo-conceptualists, which is a term used to refer to artists such as Jeff Wall (b.1946) and Stan Douglas (b.1960).

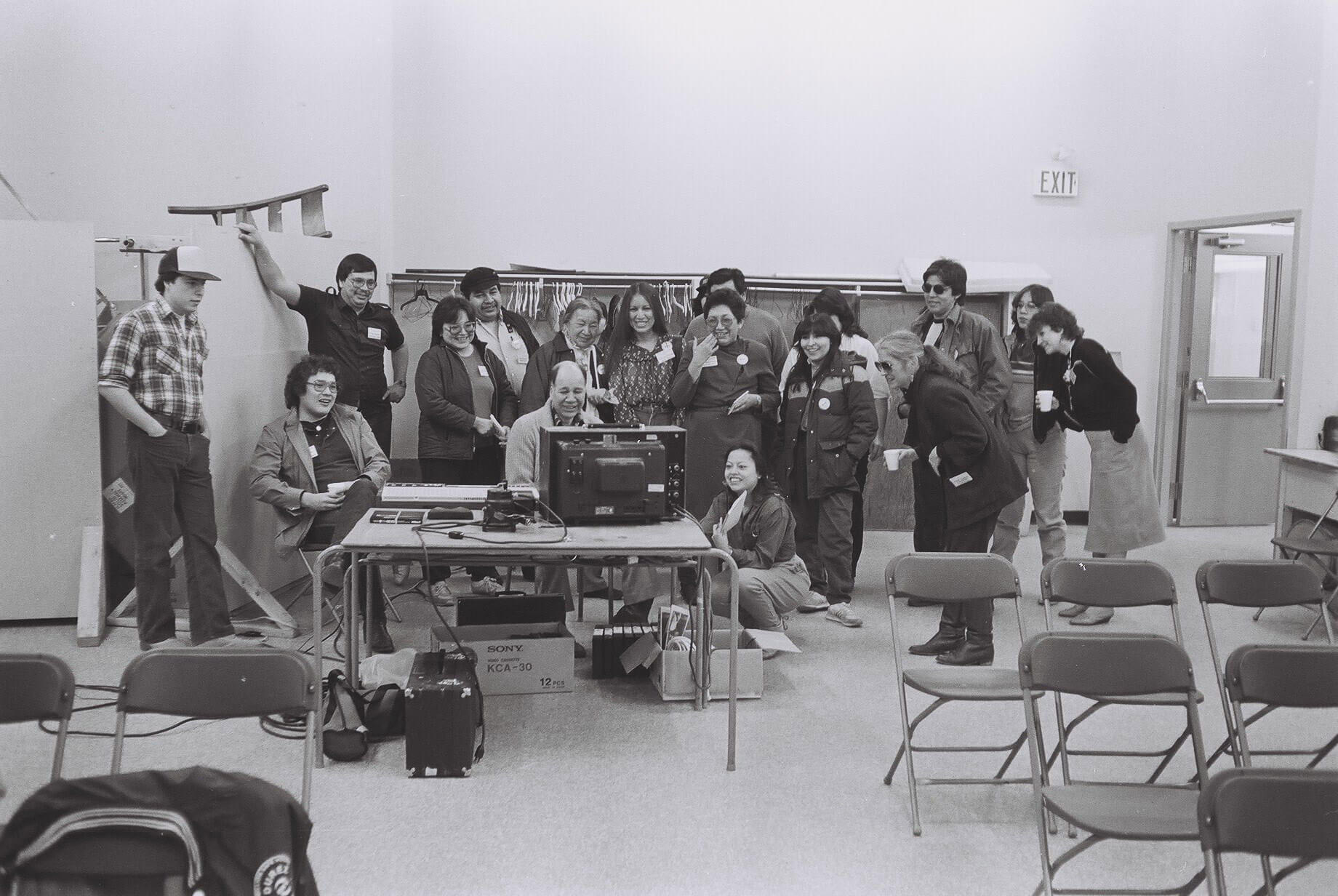

The Native Indian / Inuit Photographers’ Association was founded in Hamilton in 1985 by a collaboration of Indigenous artists, mostly Six Nations photographers living in Canada, including Greg Staats (Skarù:ręˀ [Tuscarora] / Kanien’kehá:ka [Mohawk] Hodinöhsö:ni’, Six Nations of the Grand River Territory, Ontario, b.1963) and Jeff Thomas (b.1956), but also United States–based artists like Jolene Rickard (b.1956). The initiative followed the first Indigenous photo conference in Canada and set about to “promote a positive, realistic and contemporary image of native people through the medium of photography.” The association began within the Hamilton Photographers’ Union and led to a conference, a Canada Council grant, and two travelling exhibitions in the first two years of the organization’s founding as well as a serial publication, Crossroads. Artists Brenda Mitten and Yvonne Maracle, a co-op student at the time, directed the effort to create a sense of community and purpose around Indigenous photography. A collection of photographs from the first exhibition, VISIONS, was purchased by the federal government in the 1980s and is now held by the Indigenous Art Centre, Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada.

In 1979, Claudia Beck, director of the Nova Gallery in Vancouver, made this statement at a conference on Canadian photography: “there are three requirements for a healthy art scene—artists producing good work, a network of museums and critics to validate it, and a commercial gallery infrastructure to distribute it.” Although the Massey Report of 1951 had offered support for artists, institutions, and publications, the third aspect of Beck’s call, for distribution, was still a challenge. Institutions from banks to museums collected art, but commercial gallerists struggled to build a wider market for photography in Canada.

Still, there were some intrepid entrepreneurs willing to take this on. One of the earliest commercial efforts in Toronto was the Baldwin Street Gallery of Photography. The gallery was opened in 1969 by photographers Laura Jones (b.1948) and John Phillips (1945–2010), both of whom had recently left the United States as conscientious objectors to the Vietnam War. The gallery sold contemporary Canadian photography and became an active workshop hub for the Women’s Photography Co-op, which included June Clark (b.1941) and Pamela Harris (b.1940). Jane Corkin’s eponymous gallery, a more comprehensive commercial model, opened in 1978. In addition to selling contemporary work, Corkin brought historical and modern photography to Toronto audiences, including vintage prints by famed photographers like Eugène Atget (1857–1927) and Diane Arbus (1923–1971), which were of interest to photographers as well as collectors.

Festivals such as Le Mois de la Photo in Montreal (founded 1989) and CONTACT in Toronto (founded 1997) linked commercial and non-profit exhibition venues and leveraged growing global interest in photography as a collectible art form. The festival organizers, including CONTACT’s dealer Stephen Bulger, secured corporate and government support to increase demand for photography. However, as with artists working in other media, even with a growing market for photographs as art, many modern and contemporary photographers supported their careers through exhibition fees, freelance work, and teaching positions, rather than the sale of photographs.

1948–1989: Photographic Training

In the mid-twentieth century, the training of photographers moved to technical colleges, art schools, and universities. One of the earliest schools for the study of photography in Canada was Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU), founded in 1948 as Ryerson Institute of Technology to teach technical and workplace skills. In photographic terms that meant photojournalists and people who specialized in scientific, advertising, fashion, and other commercial photography received training about technique and technology.

In the late 1960s and 1970s, educational institutions often came under the direction of influential faculty and the networks they created with and among students and the wider artistic communities. These influences had a direct impact on the styles of and approaches to photography. By the early 1970s, photographer Dave Heath (1931–2016) at TMU had moved away from the technical and commercial approach to photography. Heath integrated more creative and humanistic approaches into the university curriculum by drawing on his own experience as a street photographer. Later in the 1970s, art historian Marta Braun introduced courses in the history of photography. Several students of this era followed artistic careers, including Marian Penner Bancroft (b.1947), Edward Burtynsky, and Robert Burley, who then returned as a long-time faculty member. Students were exposed to a diversity of approaches to photography through a study collection, which began with samples of photographs by faculty and visiting artists and which is now called The Image Centre.

At York University, Michael Semak edited a collection of his students’ work for a 1974 edition of Impressions magazine. The experimental and often abstract photographs, including work by a young Larry Towell (b.1953), reflected the wider context of photographic instruction embedded in a visual art program, which at the time was the only university-level program in Toronto.

At the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design (NSCAD), Garry Neill Kennedy (1935–2021) transformed the college during his tenure as president (his term lasted from 1967 to 2000) from a conservative regional art academy into an international hub for Conceptual art. Among the international photo-based artists, theorists, and critics who came to Halifax and taught, exhibited, and published in photography were American feminist artist Martha Rosler (b.1943), Swiss American photographer Robert Frank (1924–2019) (whose book The Americans was published in 1958), and critic and theorist Benjamin Buchloch, who supervised NSCAD Press during its most influential years in the late 1970s and 1980s. NSCAD shaped a generation of artists, including Vikky Alexander (b.1959), who graduated in 1979, the same year Susan McEachern (b.1951) began teaching photography there.

Similar networks emerged at other institutions. At the University of Ottawa, NGC photo curator James Borcoman taught a course on the history of photography in 1973, followed by Penny Cousineau-Levine in the late 1970s. At the same time at the University of Ottawa, Lynne Cohen and Evergon (b.1946) taught in the studio area. Evergon soon left for Montreal’s Concordia University, where the photo faculty included Tom Gibson, Raymonde April, and Geneviève Cadieux. Given its international reputation for contemporary photography, Vancouver had not one but two educational hubs: the Emily Carr University of Art + Design included Marian Penner Bancroft, Ian Wallace, and Sandra Semchuk as faculty; and Jeff Wall, Ken Lum (b.1956), and Roy Kiyooka (1926–1994) have all served as faculty at the University of British Columbia (UBC). As programs for photographic training flourished at colleges and universities across the country, a new generation of artists and photographers extended their practices in new directions.

About the Authors

About the Authors

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements