Common genres of photography in Canada include portraiture, personal photography, art, landscape, documentary, photojournalism, ethnographic studies, and advertising. But genres are porous and relate to cultural conventions as well as how images are made and where they circulate. Critical issues change with the times and often connect with broader cultural concerns. In the 1970s and 1980s, when historians and theorists first began to critically examine photography as a field of study, they were often interested in issues of class, gender, and power. More recently, scholars have focused on how photography shapes concepts of race and mediates relationships between people. This section looks at the intersection of genres and critical issues to highlight some of the key concerns in the scholarship.

Imagining Identity through Portraiture

Portraiture is a longstanding category of artistic production. However, until the arrival of the camera, the labour and cost of painted portraiture placed it out of reach for most Canadians. Photographic portraiture played an important role in enhancing the profile of public figures, but it was also significant for making marginalized communities increasingly visible. Portraits are the result of a structured encounter between subject and photographer. Whether the portrait is made at the request of the sitter or the photographer, or due to an external commission, it requires collaboration. Although the forms of portraiture changed dramatically from the daguerreotype studio portrait to portraits with a hand-held camera, this genre of photography has long been an important way for people to express their aspirations and imagine new identities.

When Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre first announced his invention of the daguerreotype in 1839, he did not see portraiture as a suitable application for the new technology due to long exposure times of up to fifteen minutes, during which the sitter would have to stay completely still. However, within a year, portraits became the most popular type of photograph thanks to improvements in exposure times and the development of headrests that helped sitters to hold still. Later in the 1800s, the decreasing price of photographic portraits and increasing ease in producing them made them widely accessible. In addition to framed prints and albums, portraits were gifted as visiting cards (cartes-de-visite), embedded in jewellery, and in one remarkable late-nineteenth-century Canadian example in the Art Gallery of Ontario collection, slotted into an elaborate wooden sculptural display.

Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, portraiture played an important role in shaping understandings of class, race, sexuality, gender, and ability. When we look at thousands of studio portraits, there is a certain repetitive sameness to the space, the outfits, the lighting, and the poses. However, for many sitters, the ritual of sitting for a portrait was itself a powerful statement of status and belonging. Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald and his wife Agnes commissioned William Topley (1845–1930) to take portraits of their daughter Mary from her birth onward. At a time when many families chose to hide disability, the Macdonalds renovated their house to ensure Mary could fully participate in social activities, including portraiture. Topley’s elegant portraits remain a rare example from the time of a sitter with a disability.

Portraiture, especially portraits of artists, was a popular choice among Pictorialists. A 1935 portrait of Toronto-based singer Phyllis Marshall by Violet Keene Perinchief (1893–1987) pictures her looking directly at the camera, chest bare, wearing a headscarf and large hoop earrings. The photograph’s title, African Appeal, Phyllis Marshall, reflects the limits placed on Black Canadians in the visual and performing arts.

Since the introduction of photography, portraits have played a crucial role in connecting communities within Canada to families around the globe as the settler-colonial nation has been fuelled by waves of immigration. The Montreal studio of William Notman (1826–1891), for example, offered visitors the opportunity to be pictured in Canadian winter scenes ranging from an outdoor sleigh to a simulated ice rink, complete with costumes and props. These portraits often surface in family albums of British officials. Scholar Carol Williams has argued that the emphasis on child portraiture by Hannah Maynard (1834–1918) at the turn of the twentieth century in Victoria reflected the intense desire for settler women to reproduce as their contribution to the colonizing mission.

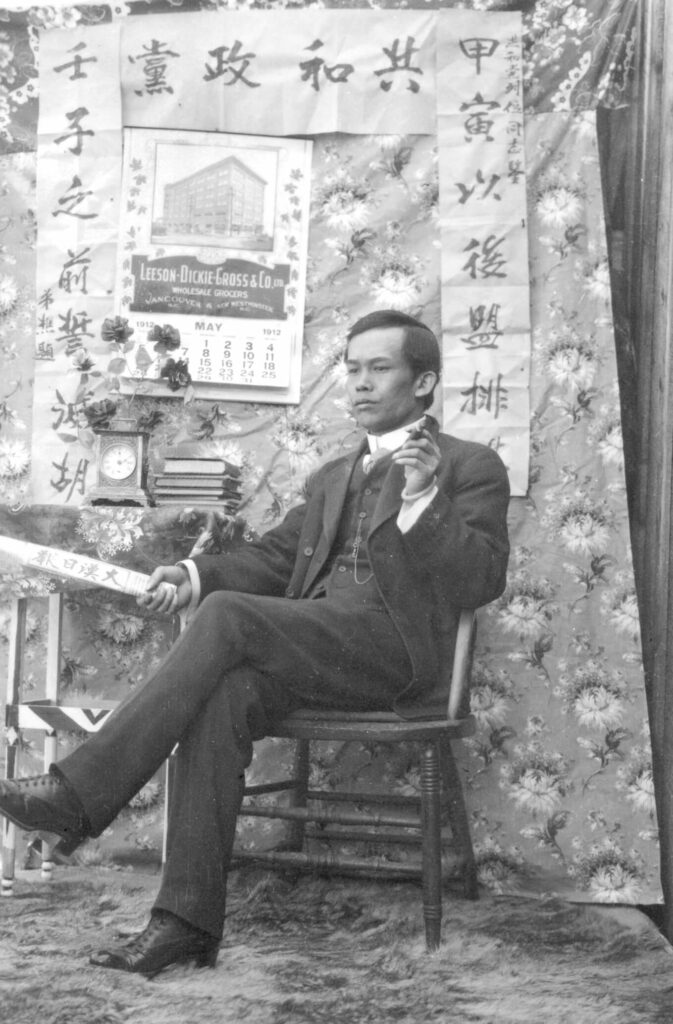

Also seeking portraits in the early twentieth century were mine workers who frequented studios like those run by C.D. Hoy (1883–1973) in Quesnel, B.C., and the Hayashi Studio in Cumberland, B.C. These studios served a range of patrons, but they also offered particular props and backdrops tailored specifically for Chinese and Japanese sitters. Working together, photographers and sitters crafted images of prosperity among wider communities in Canada.

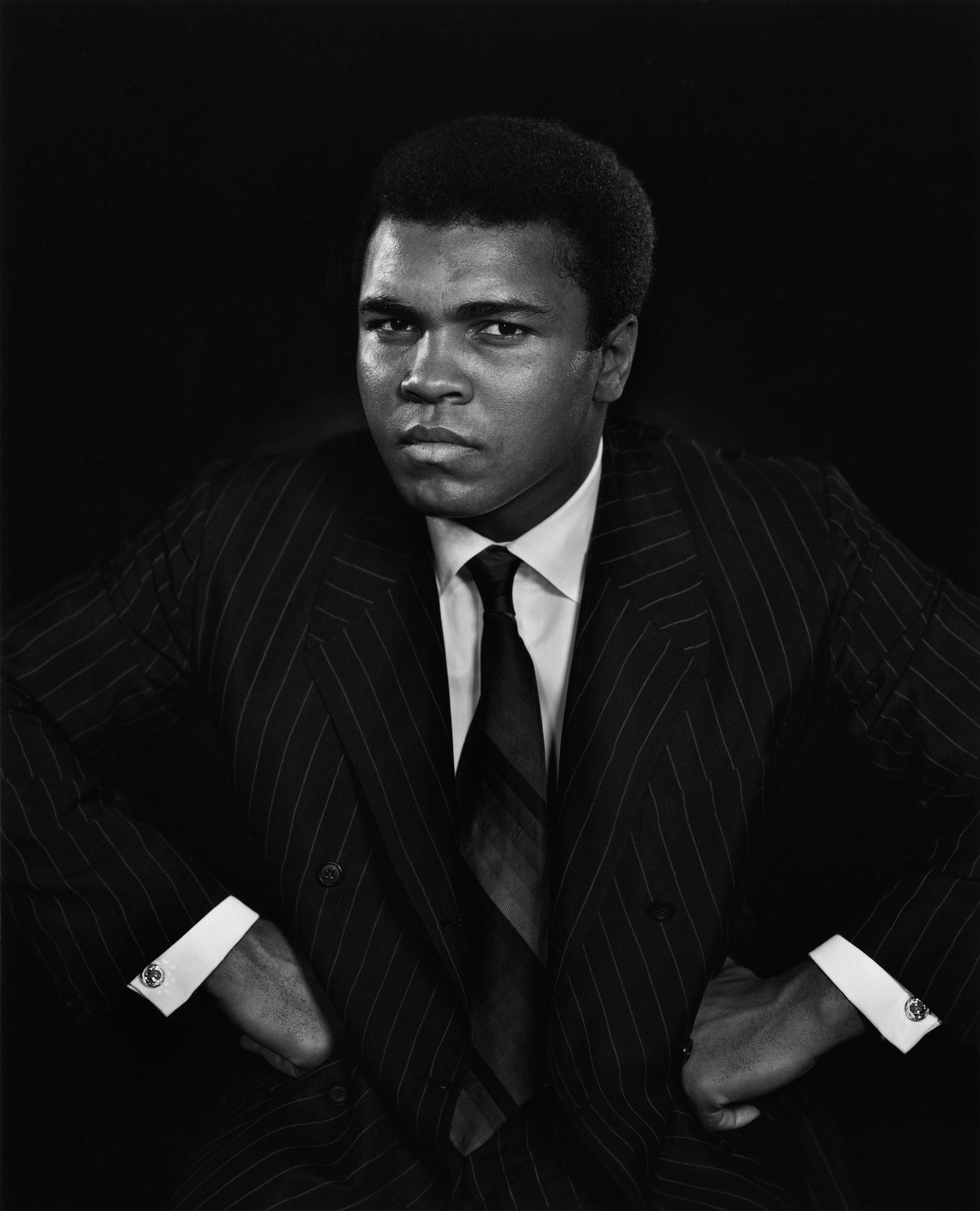

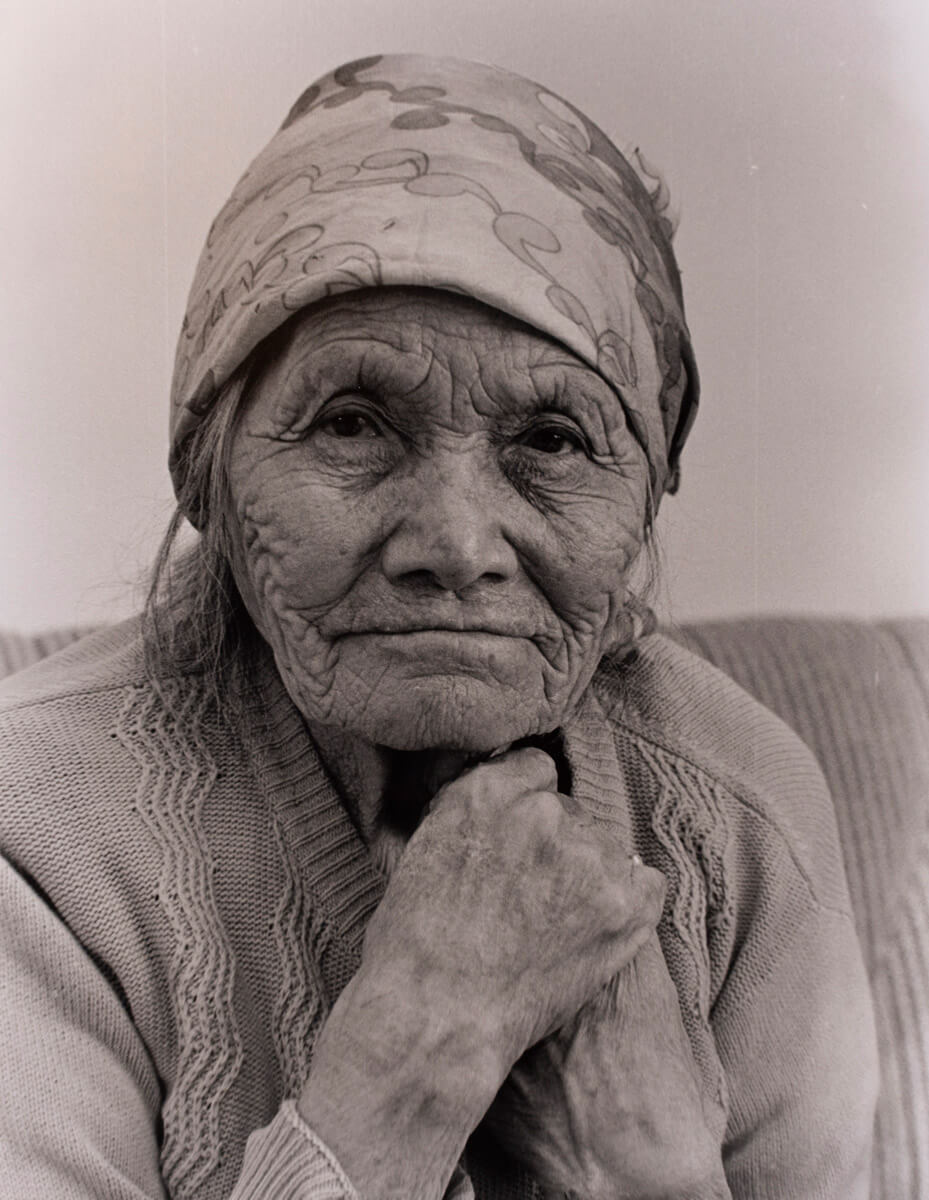

Photographic portraits are exceptionally effective tools to honour the subject, a way to elevate and celebrate the sitter’s positive attributes, such as beauty, fecundity, and expertise. This idealization reaches its pinnacle in publicly oriented portraiture, such as the glamorous and even aspirational portraits of politicians, entertainers, artists, authors, and other luminaries, like professional boxer Muhammad Ali by Yousuf Karsh (1908–2002). But honorific portraits, as they are called, can also raise awareness of under-recognized figures, as in the case of portraits of Northwest Coast Indigenous artists by Ulli Steltzer (1923–2018) made in the 1970s during a period of cultural revival.

The power of the portrait is both its specificity and its comprehensive mapping of the social system. Photo theorist Allan Sekula (1951–2013) noted that when we look at honorific portraits of public figures, we implicitly consider them in relation to a shadow archive of repressive portraits, such as mugshots. In concert with burgeoning social sciences in the late nineteenth century, marginalized sitters, such as the poor, criminals, and people of colour, were photographed as part of a larger social project to manage and control them. Hannah Maynard’s business may have focused on celebrating the health and development of babies and children, but she also worked for the Victoria Police Department taking mugshots. A mugshot has two functions: it aids in the containment and recapture of the sitter if they are sought by police in the future again, but it also identifies accused criminals and lays the groundwork for profiling on the basis of race, mental illness, and other factors.

By the late twentieth century, modern and contemporary artists were exploring the complicated history and social function of portraiture. In 1973, Suzy Lake (b.1947) produced Miss Chatelaine, a work that features a grid of twelve self-portraits of Lake clad in white makeup, displaying slightly different hairstyles and accessories, and adopting poses drawn from the limited range of options offered to women in mass media. The photographs are hardly an authentic representation of Lake herself.

In the early 1980s, Arnaud Maggs (1926–2012) also used the grid format for photographic portraiture, often depicting fellow artists. In contrast to Karsh’s own highly dramatic portraits, Maggs created a portrait installation formed of forty-four black and white headshots of Karsh. Like Lake’s self-portraits, the almost identical, repeated images of Karsh wearing the same suit and hat question whether photography can ever capture the essence of a subject. Instead, Maggs’s multiple images of Karsh facing the camera and in profile conjure a police lineup more than a traditional portrait. Whether they capture the essence or simply the surface of their subjects, Lake’s self-portraits and Maggs’s repeated images seem to foreshadow the dominant forms of twenty-first-century digital portraiture.

When you think of personal photography, the family snapshot might be the first image that comes to mind, but personal photographs can come from many sources, and in that sense the genre is defined by how it is collected and circulates. Personal photography takes in everything from the amateur images made with a Kodak camera to the tourist postcards stuck into a family album, often alongside studio portraits or even photographs cut out from newspapers or magazines. Personal photography encompasses photographs and albums made by everyone from soldiers and students to community groups and families—both biological and chosen—to document shared experiences.

Albums and other forms of personal collections draw attention to how we use photography to understand our histories and social connections. And our relationship to these materials is often as tactile and emotional as it is visual because these photographs are often touched, shared, hidden away, and sought out when needed. In the pre-digital age, personal photographs and family albums were often among the most treasured possessions. Like many others, Hon Lu’s family prioritized family photographs as they fled their home in a time of crisis. Not only did they bring photographs among their limited possessions from Vietnam in 1979, but they also added to that archive with images of their journey to Canada.

American cultural critic bell hooks points to the power of personal archiving and display in her discussion of photography and Black life. Whether the images were found in albums or on the walls of private homes, “images could be displayed, shown to friends and strangers… images could be critically considered, subjects positioned according to individual desire.” We see that in the archive of Beverly Brown. Starting in 1937, after being sent to a residential school in Alert Bay, B.C., Brown created a rare personal archive of snapshots of life in the residential school. In defiance of the dehumanizing institution, Brown and her friends bonded through photography, and she inscribed the name and home community of each child pictured in her photos.

Studies analyzing family and other personal photography have explored a range of critical issues including identity, memory, loss, and the practices of viewing. French theorist Roland Barthes was particularly intrigued that the most benign personal photographs can trigger affect, steeped as they often are in “desire, repulsion, nostalgia, euphoria.” Scholar Marianne Hirsch has a more expansive view suggesting that family photographs can connect viewers to images even from other historical eras and cultures. This is because social conventions shape family photography: “the family photo both displays the cohesion of the family and is an instrument of its togetherness.”

Richard Bell’s gift of his family’s personal collection to a public archive is part of a wider pattern, one that offers institutions, researchers, and members of various communities the opportunity to create a fuller picture of Canadian history, as well as showcase the gaps and outright racism of state archives, including museums. The Bell-Sloman family, who came to southwestern Ontario via the Underground Railroad in the 1850s, used photography to chronicle their lives and accomplishments for more than a century.

Curator Julie Crooks describes the Bell-Sloman family’s collection of portraits, snapshots, school photos, and other documents as an opportunity to trace “histories of diasporic dispersals, fugitive movement and settlement.” Several photographs in the collection highlight the work undertaken by family members such as the snapshot of Charles Bell with the horse and cart he used to deliver ice and coal. The collection also contains a remarkable tintype, a commissioned portrait of a young woman in an elaborate feather hat and domestic uniform. Likewise included are several images of the family’s leisure activities and moments of joy and celebration.

Personal photography is often used to convey emotional bonds or even create intimacy within families or social groups. In her influential study of a range of Canadian photo albums at the McCord Museum, photo historian Martha Langford argued that what is often overlooked, but crucially important, in collections of personal photography is the way they build connection through narratives: “photo albums are not designed to inform strangers but to act as mnemonic clues for the people involved.”

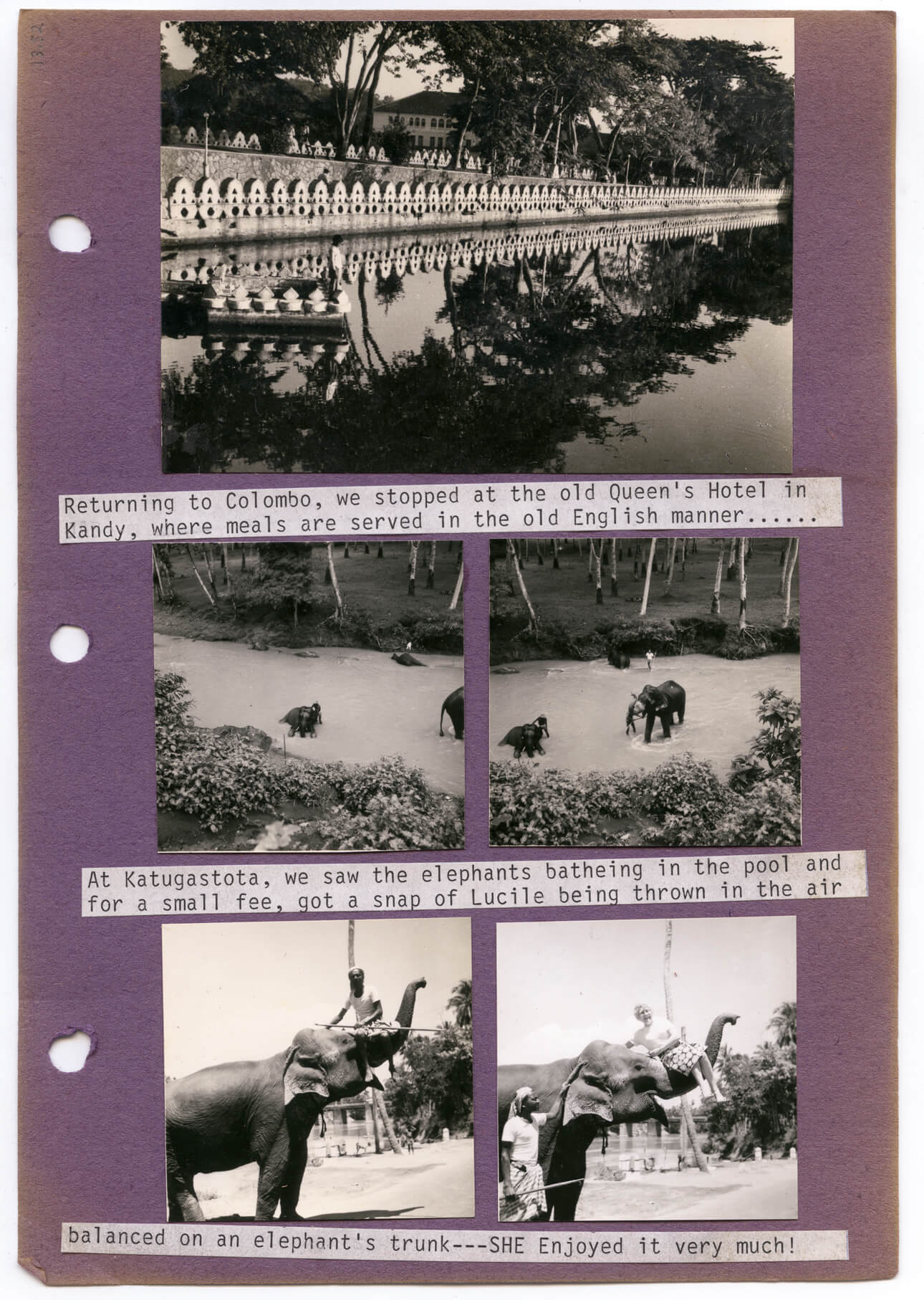

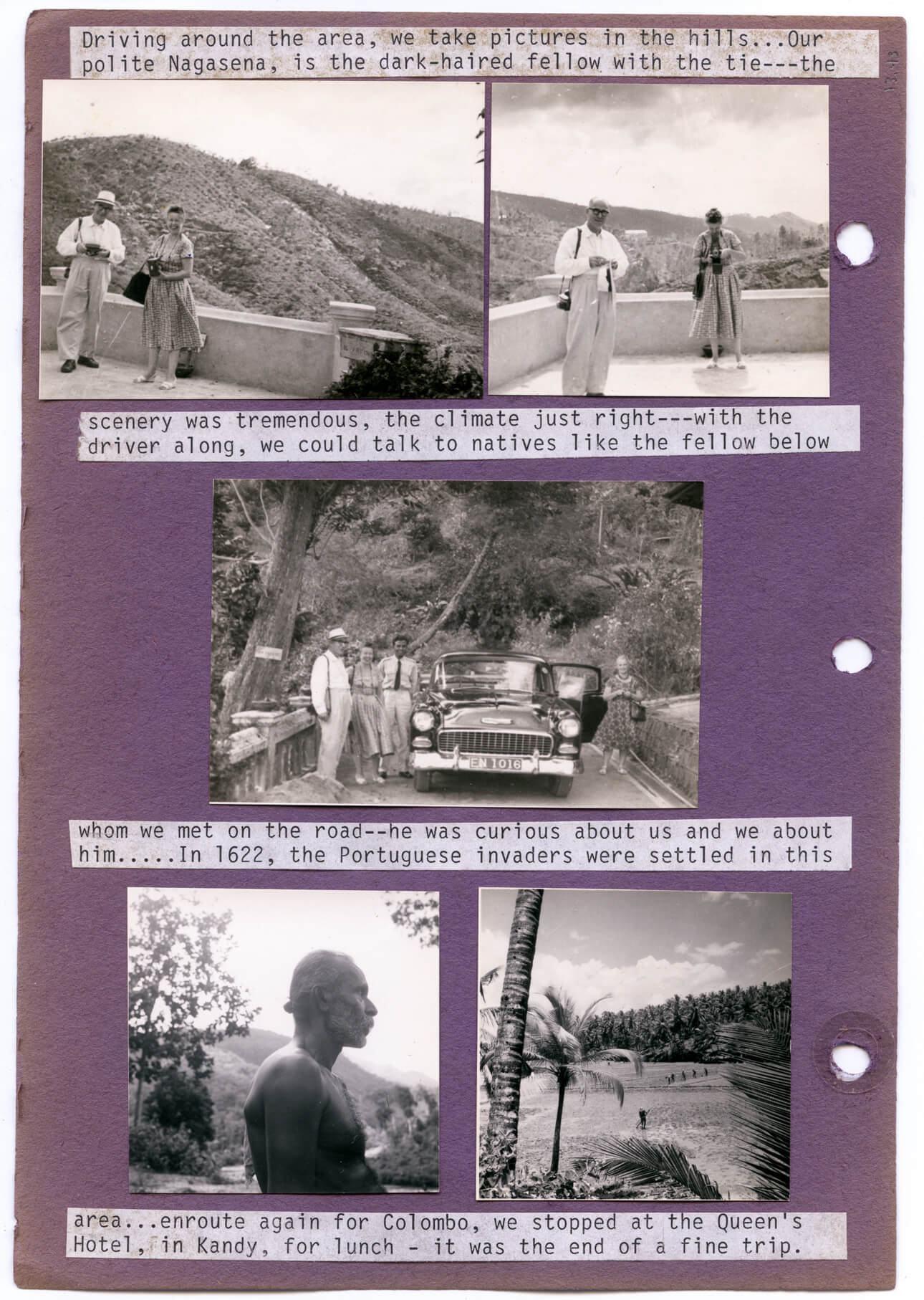

Although Langford focused particularly on oral narratives, her insights offer a helpful framework for albums such as the one created by Margaret Corry (1947–1963). Corry was a Canadian expatriate who travelled extensively in Europe and Asia during the 1940s and 1950s. She took most of the photographs herself and assembled them into a travelogue with typewritten captions and observations. She sent the albums home to Canada in an effort to connect with her family and bring them into her adventures. Her albums tell her personal story of adventure and cultural exchange within a global context of imperialism.

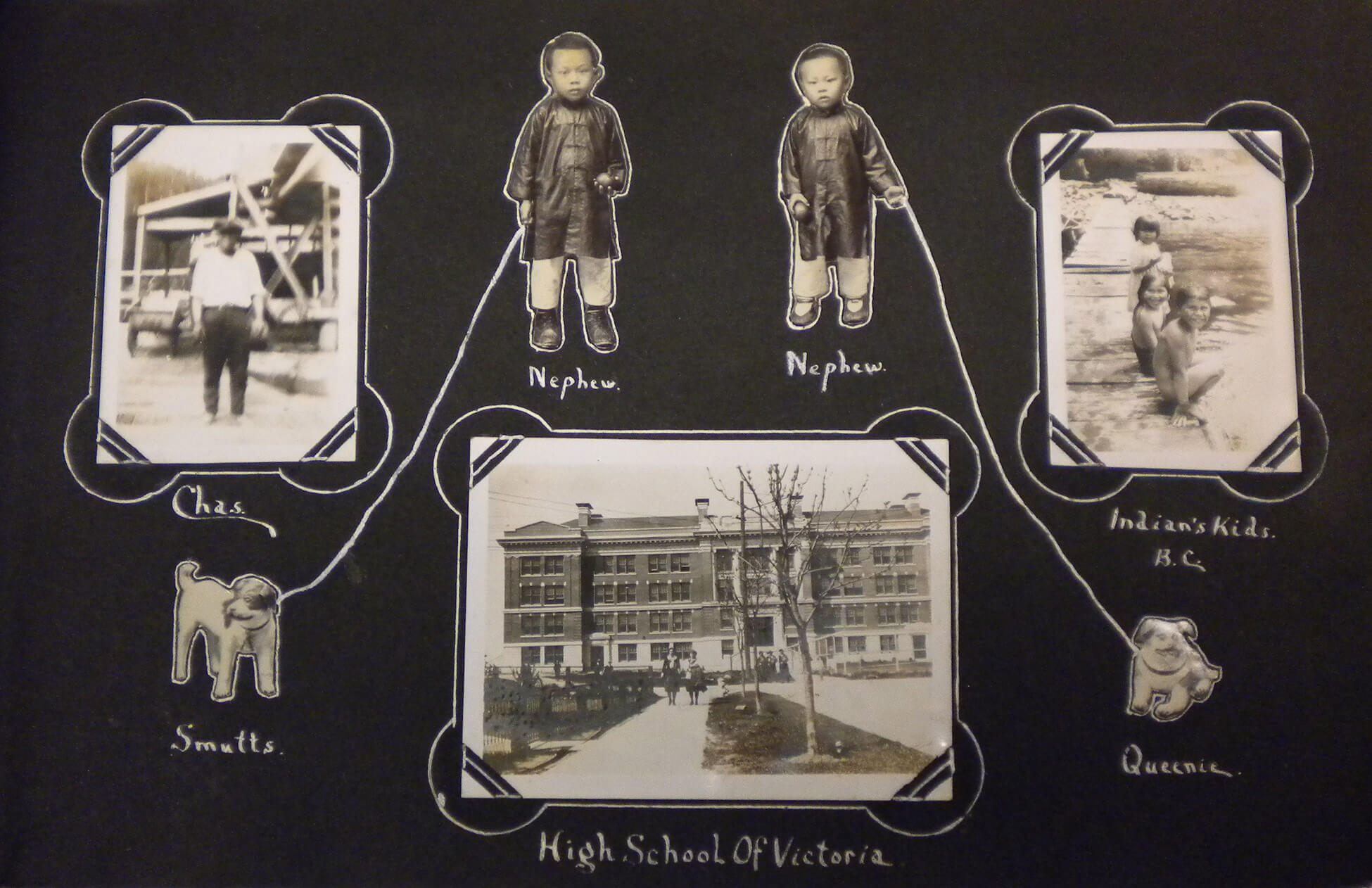

A fascinating example of a more abstract, imaginative narrative crafted through personal photographs comes from the pages of a scrapbook created by Lillian Lock in the 1920s and 1930s. Lock combined portraits of family members living in China with snapshots of her family dogs, a Canadian school, and Indigenous children on a dock. She drew lines between her young relatives in China to make it seem as though they were walking her dogs and so part of her family life in Canada. As art historian Julia Lum describes, “Lock’s album bridges the insurmountable distance between geographies and chronologies, constructing familial bonds where there were indeed none.” Lock also included photographs in the album that she clearly saw as family photographs, such as family immigration documents and a newspaper article about her mother’s 1909 arrival in Toronto, a rarity given government policies restricting Chinese family reunification. These institutional photographs carried enormous power over the personal lives of their subjects and serve as a crucial counter-archive in the family album.

The relationship between the state and personal photography is even more explicit in the context of Japanese Canadian internment camps during the Second World War. Personal cameras were not allowed in the government internment camps although many people smuggled them in, and some Japanese Canadian photographers were designated as official photographers documenting camp life. In studying the archive of surviving images, media scholar Kirsten Emiko McAllister was struck by the smiling faces in the images and that the images did not document the harsh conditions, which suggests overlapping interest among amateur and official photographers in “averting the gaze from the losses, humiliations, and intergenerational damage that Japanese Canadian families underwent in the hands of the Canadian government.” Within her own family, McAllister’s mother similarly provided a consistently celebratory narrative of their family photographs, including those made during internment.

Scholar Marianne Hirsch uses the term “postmemory” to describe the outsized power one generation’s narratives, often told through photographs, can have on the next generation. Postmemory creates inherited memories so clear that they feel real and yet the way they often elide trauma can contribute to its intergenerational impact. As McAllister demonstrates, personal photographs and their narrative scripts may work in tandem to idealize the idea of family by erasing traces of conflict and hardship.

Photography as Art

There were vigorous debates about what photography was and how it should be used for several decades after its invention in 1839, and advocates for artistic photography, such as British photographer and author Henry Peach Robinson (1830–1901), fostered its place in the arts through lectures, publications, and exhibitions in the rich cultural hubs of Europe. In Canada, photographers experimenting with the camera’s artistic potential looked to their colleagues in other countries for inspiration.

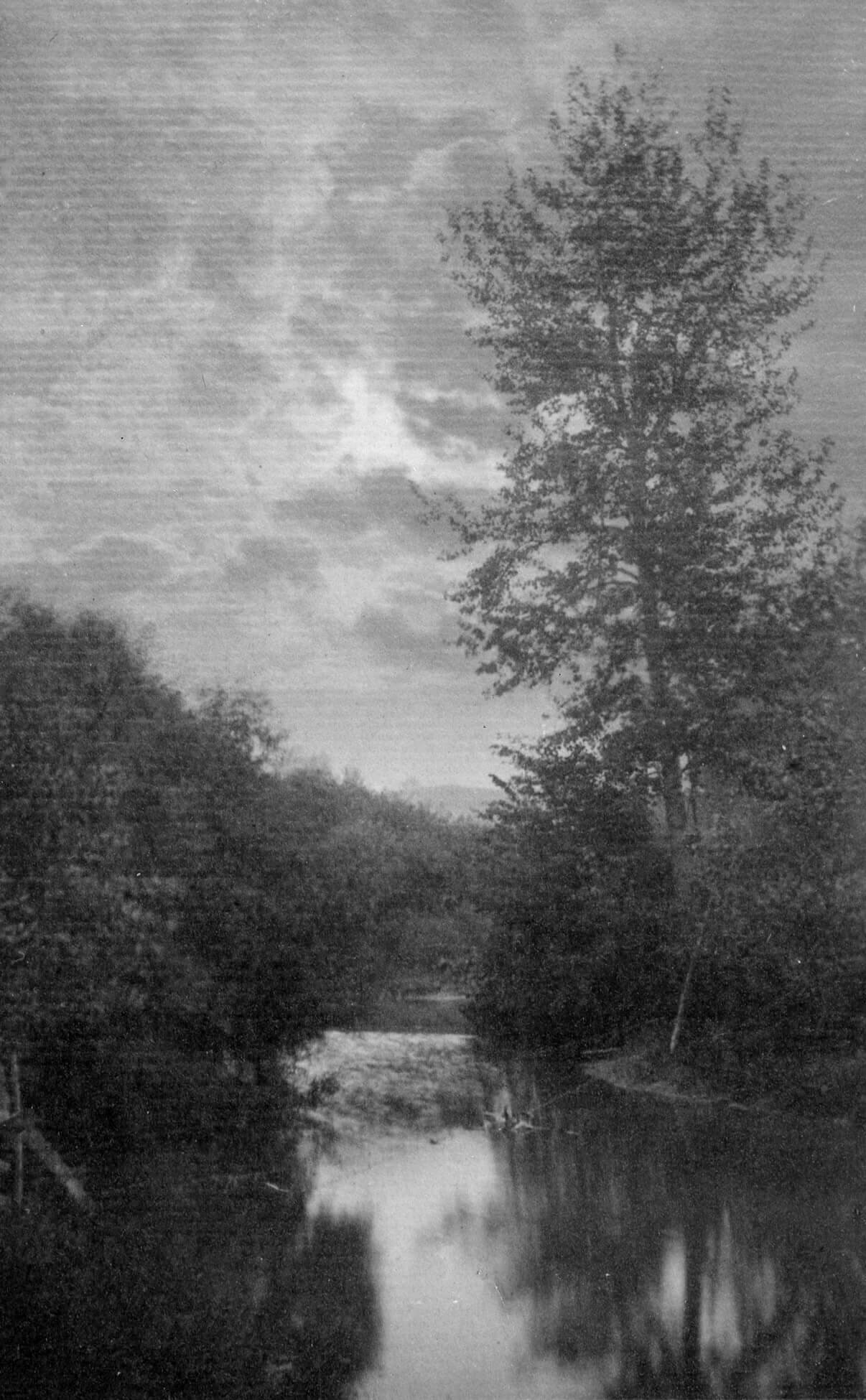

Alexander Henderson (1831–1913), who did not need to make a living from his photography, gave up his portrait business in the 1860s to focus on landscapes and views. Many of his landscape photographs follow Robinson’s call for poetic treatment and draw on numerous photographic techniques to deploy light, tone, and composition as creative tools. Henderson often submitted photographs to U.K. exhibitions and elite amateur exchange societies where his work was received as art. Seeking to build similar support for art photography in Canada, Henderson and William Notman were founding members of the Art Association of Montreal in 1860, and Notman offered his studio for the association’s inaugural exhibition, which included photographs.

Although photography was not readily embraced as an art form in mid-nineteenth-century Canada, it still played an important role in the Canadian art world. Commercially available photographs provided invaluable source material for artists, especially those working in landscape, and many commercial studios employed artists to paint photographs. For instance, John Fraser (1838–1898), who worked at Notman’s studio, was called on to paint over photographs completely so that they resembled traditional oil or watercolour portraits. Notman also sought access to art collections to document paintings photographically, which he then sold as prints and stereographs, and published in books. His efforts helped to popularize the fine arts and to augment his own cultural cachet.

By the later part of the nineteenth century, the immense popularity of stereoscopes encouraged more creative approaches to subject matter. Studio photographer James Esson (1853–1933), for example, produced Victorian genre scenes and made stereoscopic views during his North American travels. As the public’s demand for photographic content grew, photographers responded with creative performances staged for the camera, erotic images, and narrative sets of photographs of the same subject that point toward the development of moving images and film.

In the 1890s, Pictorialism became the first clearly defined international artistic movement within photography. It mined the potential of both the camera and experimental printing techniques to produce soft, sepia-toned photographs of traditional artistic subjects such as nudes, landscapes, and portraits. Sidney Carter (1880–1956) was a member of the Pictorialist Photo-Secession group in New York founded in 1902 by Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946). In 1906, Carter brought an exhibition of Pictorialist work to Toronto with the help of Harold Mortimer-Lamb (1872–1970), who also worked to establish regular salons and commercial galleries for art and photography in several Canadian cities, all while publishing reviews in international arts magazines.

Curator Ann Thomas has observed that Pictorialism persisted in Canada longer than many other places. B.C. photographer H.G. Cox (1885–1972) only took up photography in the 1920s and produced a remarkable body of work over the next decade. Cox’s fellow Vancouver photographer John Vanderpant (1884–1939) also integrated aspects of Pictorialism into his more modernist photographs, which were often taken from unusual angles that highlighted a mechanized way of viewing and representing the industrialized world.

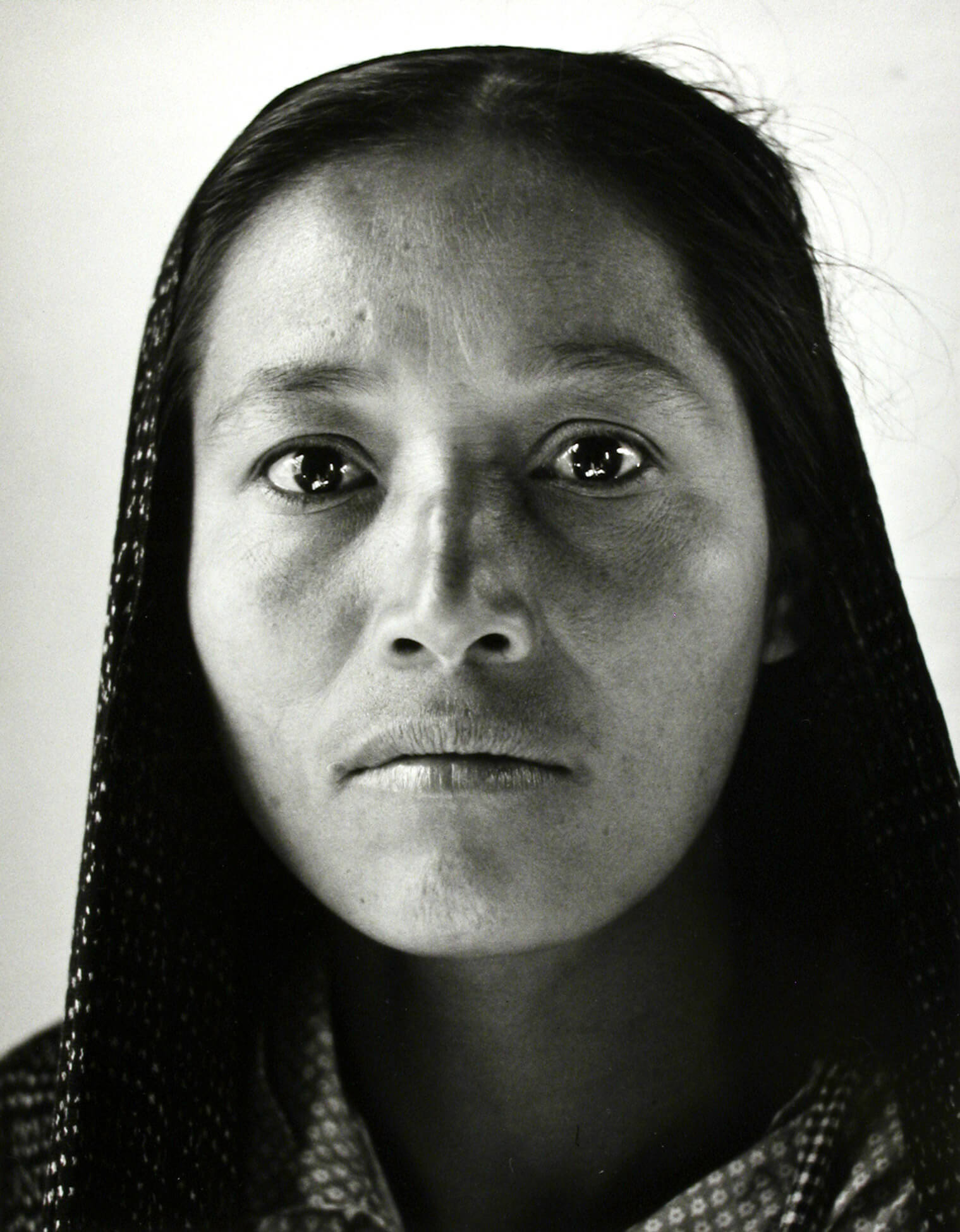

Though many think of the art realm as highly individual and avant-garde, early twentieth-century art photography in Canada was conservative. Pictorialism followed international trends, and because its development in Canada was fostered and judged by camera clubs, most of the resulting photography shared a clear set of artistic parameters. Even the modernist photography that followed Pictorialism grew out of homogeneous networks of artists, critics, curators, and gallerists. For instance, the Toronto Camera Club, which initiated many of the early exhibitions, regularly debated whether women should be full members, so there should be little surprise that the celebrated women art photographers in Canada at the time did not emerge from these clubs. Minna Keene (1861–1943) had already established her place in the Pictorialist movement in the U.K. by the time she settled in Canada in 1913. The domestic still-life photographs captured by Margaret Watkins (1884–1969) in the late 1910s and early 1920s are among the most internationally recognized Canadian modernist images and yet she was trained and produced her best-known work in the U.S. Working in Mexico in the late 1940s, Reva Brooks (1913–2004) made portraits of Indigenous people and her photos garnered international attention.

In the postwar period, new support for the photographic arts in Canada and the waves of artists arriving from other countries spurred the development of art photography in different ways. In 1951, the Massey Report outlined the need for a national arts infrastructure to fund and support artists across the country. Canada Council funding fostered the development of artist-run spaces and innovative arts magazines and supported travelling exhibitions, while the National Film Board (NFB) was developing creative photographic projects by the end of the 1960s.

Michel Lambeth (1923–1977) was one photographer who received support from the NFB and the Canada Council in the 1960s. He was born in Canada but learned photography during a six-year stay in Europe after the Second World War. He became interested in the subjective experience of the urban environment and the aesthetic possibilities of everyday life, exploring these themes in his street photography when he returned to Toronto. His photographs of the social landscape, such as Union Station, 1957, embraced aspects of the documentary style but focused on the absurdities of life rather than on advancing a political agenda. In the early 1970s, Lambeth served on the photography awards jury with Tom Gibson (1930–2021) and Charles Gagnon (1934–2003).

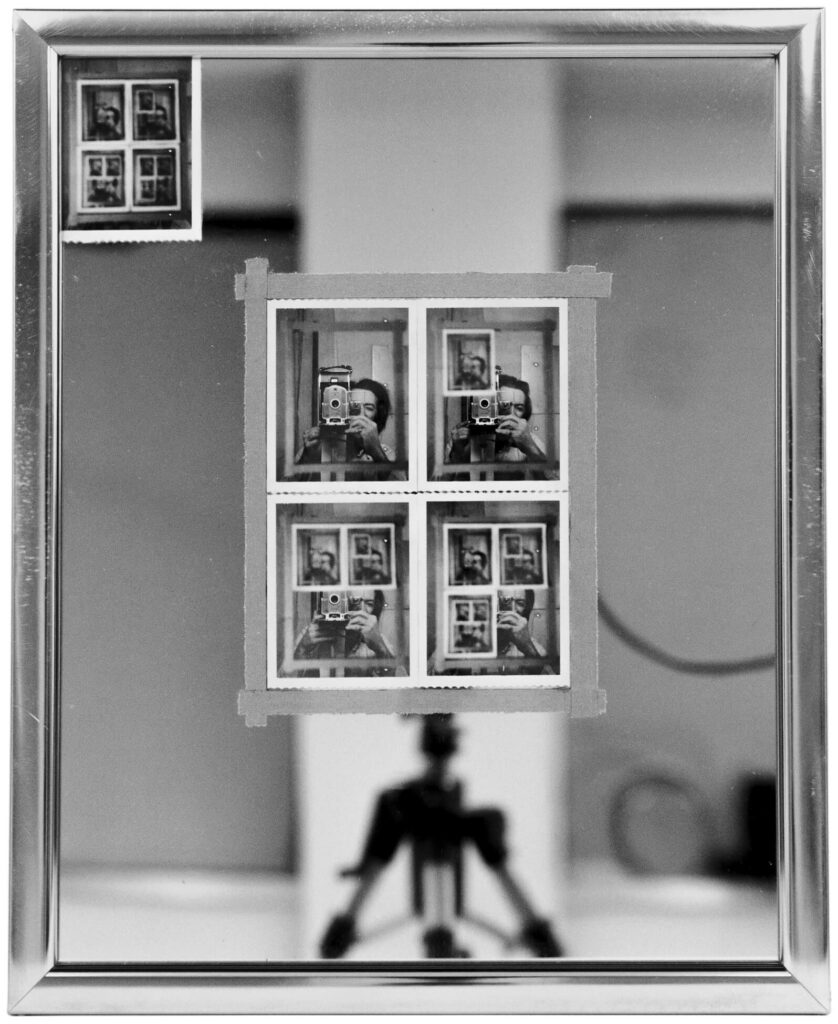

From the late 1960s on, photography played a significant role in the arts in Canada, and Conceptual artists including Sylvain P. Cousineau (1949–2013) and Stan Denniston (b.1953) made work that rejected the idea of photography as merely a tool to document the world. Others including Michael Snow (1928–2023), Jeff Wall (b.1946), Ken Lum (b.1956), and Vikky Alexander (b.1959) are among the Canadian artists with the highest international profiles. Snow once explained the Conceptual approach by saying: “to extend the depth of what has been called ‘art’ into photography requires not choosing nobler subjects, but rather making available to the spectator the amazing transformations the subject undergoes to become the photograph.” We see this concept at play in Snow’s Authorization, a work that began with a simple self-portrait taken using a tripod-mounted camera and a mirror. But Snow taped the resulting images to the mirror and re-photographed them three more times, resulting in a complex and compelling final image.

In the 1970s and 1980s, as art school training in photography blossomed along with the market and audience for photography, photo-based work was fully integrated into the contemporary art scene. Particularly notable in the 1980s is the wide range of feminist artists who shared an interest in the way gender is constituted through representation but who used photography in wildly different ways—ranging from the visual narratives of domestic life by Susan McEachern (b.1951) to the highly stylized large-scale self-portraits of Barbara Astman (b.1950).

The Aesthetics of Landscape

In Canada, landscape photographs appeared first in the form of scenic views made by commercial photographers such as William Notman and later, in the 1860s, as a subject in artistic photography. But this genre of photography derives from painting traditions dating back to Renaissance Europe. Landscape photography typically portrays a natural environment using a set of pre-existing pictorial conventions, including light, atmosphere, composition, and recession in space. In the 1840s and 1850s, landscape photographers grappled with technical challenges such as depth of field (which affects how much of an image is in focus), the absence of colour, the smaller size of a photograph compared with a painted canvas, and the difficulty of registering clouds and sky, which often required a different exposure than the land. Other challenges included spatial arrangement, weather, and movement.

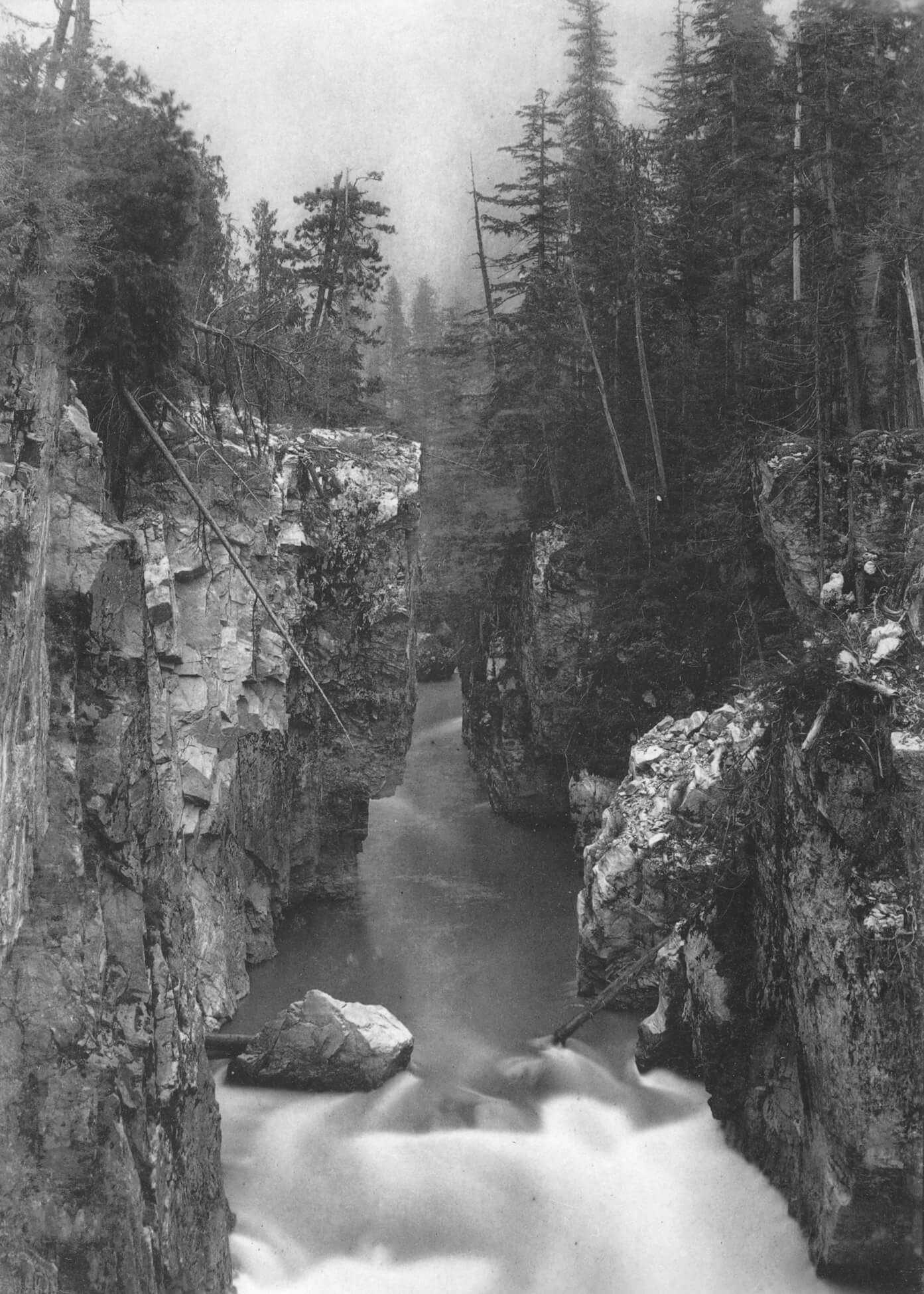

Despite these obstacles, photographers such as Alexander Henderson, working in Quebec in the 1860s and 1870s, achieved success and gained international recognition for picturesque views such as the striking image, Cape Trinity, Saguenay, c.1865–75. Henderson adapted conventions of landscape painting, using formal devices to create a distinct foreground and background to convey a sense of depth. In some instances, Henderson included foreground features to frame an image, giving viewers a sense of visual proximity. Henderson’s prints sold well with tourists keen to remember Canada for its natural beauty. Photographers like Sally Eliza Wood (1857–1928) continued to feed this market through the early twentieth century with postcard views of eastern Quebec.

Landscape was accepted as an aesthetic category in art photography during the Pictorialist movement, beginning around the turn of the twentieth century. Sidney Carter, Charles Macnamara (1881–1944), and others created soft focus gum bichromate prints with subtle tonalities, emulating the atmospheric effects of tonalist and Impressionist landscape painting. Artistic works such as Carter’s Evening Sunset on Black Creek, c.1900–01, portray the land as domesticated and as existing for the pleasure of the viewer. At the same time, some photographers were exploring the aesthetics of landscape, others were making pictures of the land that constructed concepts of place and negotiated power over and ownership of land and resources.

Government geological surveys in the 1860s–90s were important to settler colonist ambitions, land acquisition, and resource development. Occasionally, these photographs depart from aesthetic conventions as they are lacking a gentle recession into space, a penetrating line of sight, and interesting foreground features, such as in the work of Joseph Burr Tyrrell (1858–1957), made during an 1886 survey in Alberta with the Geological Survey of Canada. Using an approach similar to survey photographers of the American West, some practitioners in Canada attempted to translate the environment into a pictorial form of information to support an idea of the West as largely uninhabited and available for European settlement.

Nonetheless, there was not a strict separation between images that followed aesthetic conventions and those that were made in the name of science and progress. Dramatic landscapes by Édouard Deville (1849–1924), the Surveyor General of Canada, are a case in point, because he conveyed the beauty of a scene even as he made photographs for information about the land. No matter the pictorial structure, landscape is not something “‘out there’ waiting to be recorded.” Rather, as historical geographer James Ryan reminds us, it is a way of conceiving of the world that privileges the perspective of “a detached, individual spectator.”

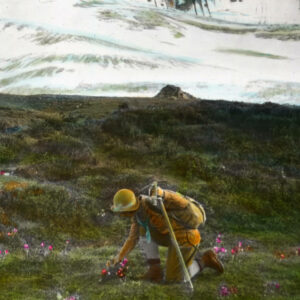

Alongside government surveys and commercial enterprises to produce postcards and scenic views are independent explorations, often by women. Mary Schäffer (1861–1939), for instance, travelled through the Canadian Rockies in the early twentieth century and made photographs of the landscape and flora that she showed in lantern slide lectures and published in illustrated travelogues.

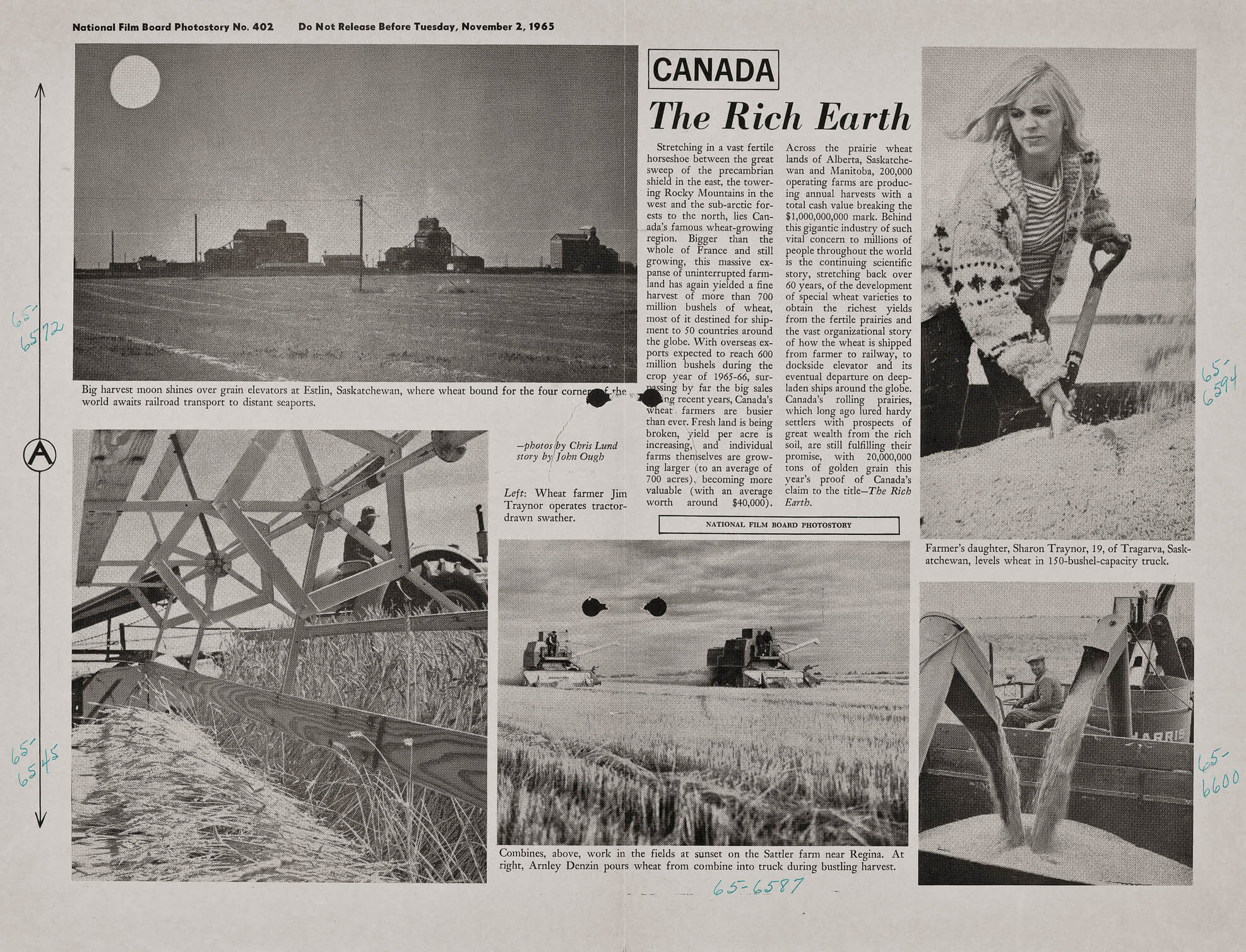

The landscape genre accommodates all manner of scenes, including those that focus on the exploitation of nature. Given the importance of resource extraction to Canada’s economy, numerous practitioners have photographed industrial landscapes. In these photographs, the emphasis is less on nature and more on the infrastructure of agriculture, forestry, and mining. Working as a documentary photographer in the 1950s and 1960s, George Hunter (1921–2013) photographed the industrial sector, including oil and gas, forestry, and mining. His work recognizes the role of natural resources and industry in the booming postwar economy.

Over the course of the twentieth century, Canadian perspectives on industry changed significantly, and the initial celebratory tone of the earlier work of photographers gave way to critical investigations of land use, pollution, and the human impact on the environment. The growing concern regarding the environmental consequences of human activity in the 1970s led some photographers to explore the idea of the human-altered landscape. Artists offering commentary on the state of the environment include Edward Burtynsky (b.1955), who began producing large-scale, richly coloured, and highly detailed photographs of mine tailings, marble quarries, and oil fields, and Geoffrey James (b.1942), whose panoramic landscapes of European gardens and villas tell a different story about the domestication of nature. The series of majestic black and white photographs of the remains of Rockland Bridge, New Brunswick, by Thaddeus Holownia (b.1949) illustrates the impact of a wider battle between humans and nature. The ongoing destruction of a 200-year-old bridge on the Bay of Fundy points to potential fallout from the meeting between human hubris and the power of nature.

Conceptual artists also worked with photography to critique romantic ideals of landscape and deconstruct colonial power relations. The photographic series by American theorist and artist Allan Sekula, Geography Lesson: Canadian Notes, which toured North America in 1986 and 1987, visualized Canada as a land shaped by the demand for natural resources. Long Beach BC to Peggy’s Cove Nova Scotia, 1971, by Roy Kiyooka (1926–1994) is a photo series and travel narrative of the artist’s sensory and emotional experience relating to his move from Vancouver to Nova Scotia for a teaching position at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design (NSCAD). Moving from west to east, and composed of image fragments, Kiyooka emphasizes geographic displacement and disrupts the idea of the Trans-Canada Highway as a symbol of national unity.

Another work that uses the grid format is by Marlene Creates (b.1952). Sleeping Places, Newfoundland, 1982, shows the artist’s imprint on the land from places she slept during a two-month journey around the island. In this work, Creates established a relationship with the land that was about memory and experience rather than dominance and control. For these Conceptual artists, photography offered a means of contesting conventional Western ideas about the world.

Photography as Evidence and Communication: Documentary and Photojournalism

A photograph from 1893 showing people gathered around a broken section of the intake pipe that supplied water from Lake Ontario to the residents of Toronto illustrates how images have long been used to record noteworthy events. This disruption to the city’s water supply caused an outbreak of typhoid fever; shortly after the photo was taken, the city engineer modernized the water system.

-

F.W. Micklethwaite, Waterworks upheaval, 1893

Black and white photograph, 16 x 20 cm

City of Toronto Archives

-

Page 21 of Charles Hastings, “Report of the Medical Health Officer dealing with the Recent Investigation of Slum Conditions in Toronto, embodying Recommendations for the Amelioration of the Same,” 1911

City of Toronto Archives / Toronto Public Library

-

Lewis Benjamin Foote, Interior of 109 Henry Avenue, Winnipeg; Blood-spattered kitchen after fatal stabbing with a pocketknife, 1922

Gelatin silver print, 19.7 x 24.8 cm

Archives of Manitoba, Winnipeg

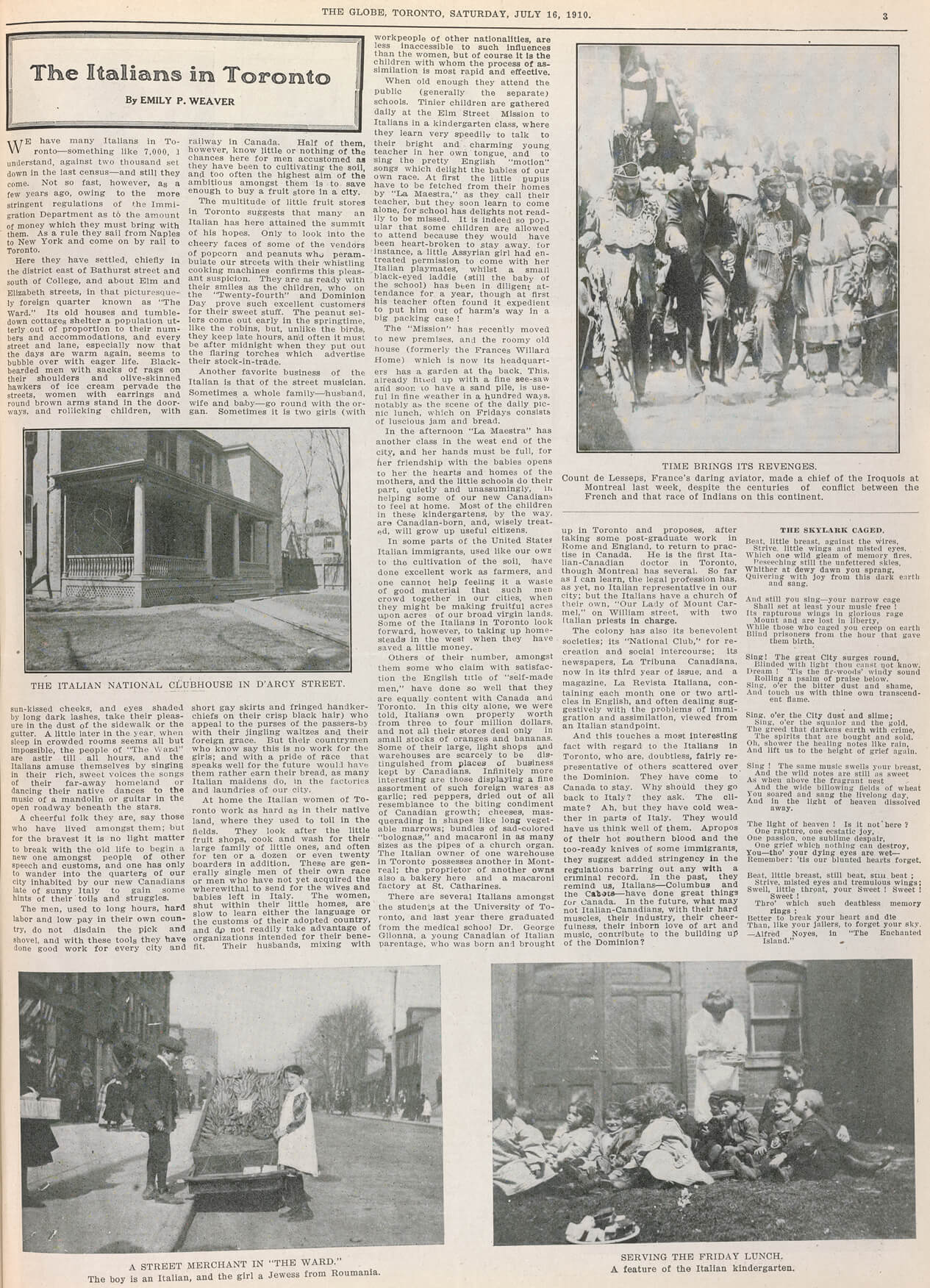

During the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, municipal governments in growing urban centres such as Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg used photography not only to record events but also as evidence to manage perceived problems, such as poverty and criminality. Photography was an important tool in urban reform initiatives, such as the Medical Health Officer’s surveys of living conditions in downtown Toronto, and in policing, where photographers took mugshots for identifying criminals and made forensic photographs of crime scenes.

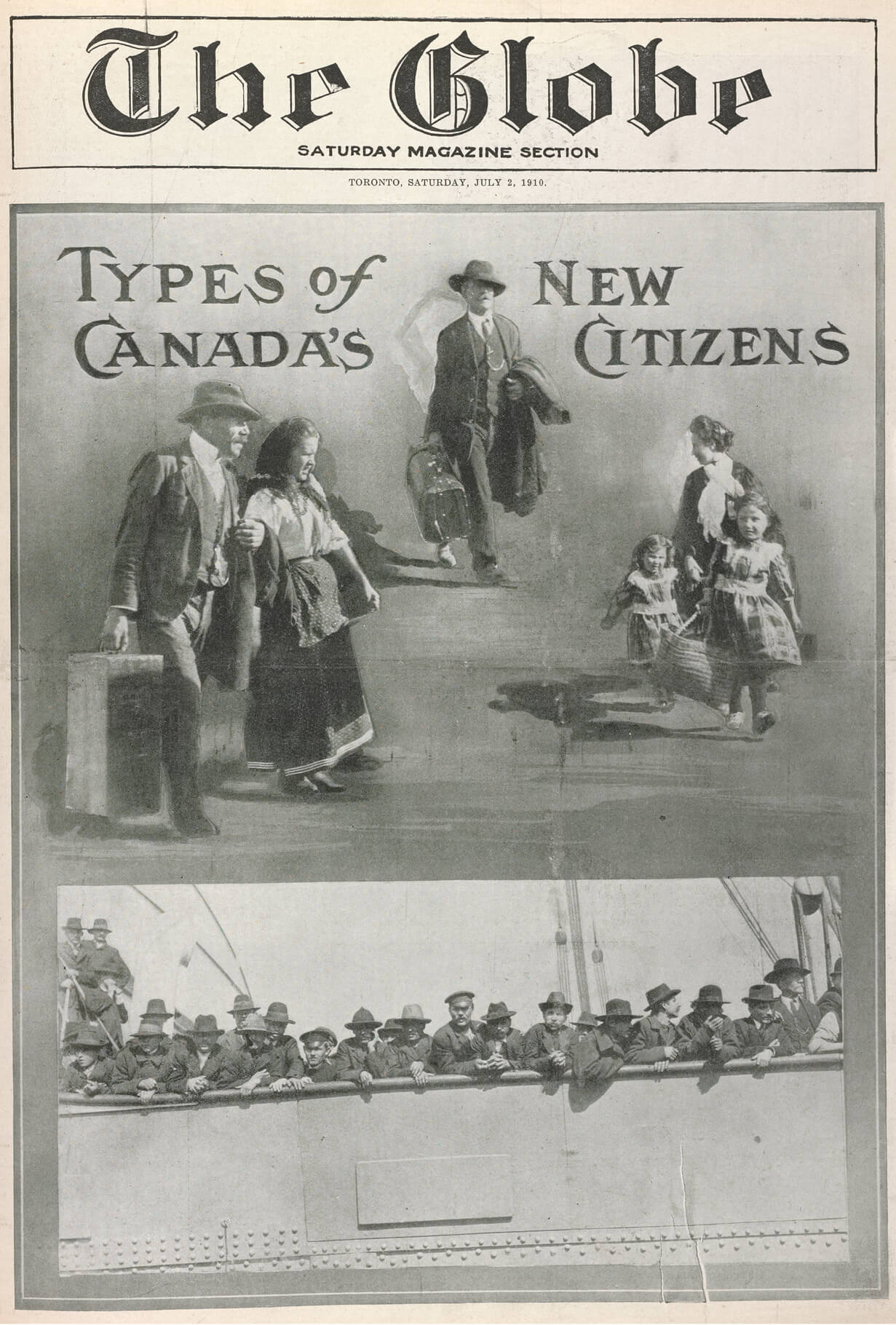

Photojournalism developed in Canada in the early twentieth century when newspapers and magazines began publishing photographs in illustrated weekend sections. Photographers such as William James (1866–1948), Jessie Tarbox Beals (1870–1942), and Lewis Benjamin Foote (1873–1957) were at the forefront of the field. The popular illustrated supplements of this time helped newspapers boost their circulation and generate a sense of connection to others. News agencies that published papers and magazines adapted the use of photographs to target different readerships and to convey different perspectives. For instance, The Globe, a newspaper aimed at well-off professionals and the business community, was allied with the federal Liberal party and supported Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier’s immigration agenda. To this end, it published illustrated stories, including one by journalist M.O. Hammond (1876–1934), in its Saturday magazine emphasizing the role of immigrants in nation building. The illustrated format appealed to readers’ emotions and encouraged a sense of social responsibility. By 1922, the increased demand for pictures led The Globe to hire John H. Boyd (1898–1971) as its first staff photographer.

Photographers were not normally credited for their work in newspapers and magazines in the early twentieth century, so Edith Watson (1861–1943), who made her living in travel photography, was ahead of many of her colleagues by insisting that she receive credit as well as payment for her images. With stories about women in rural communities published in popular magazines such as Canadian Magazine and Maclean’s, Watson brought a Pictorialist aesthetic to a mainstream readership.

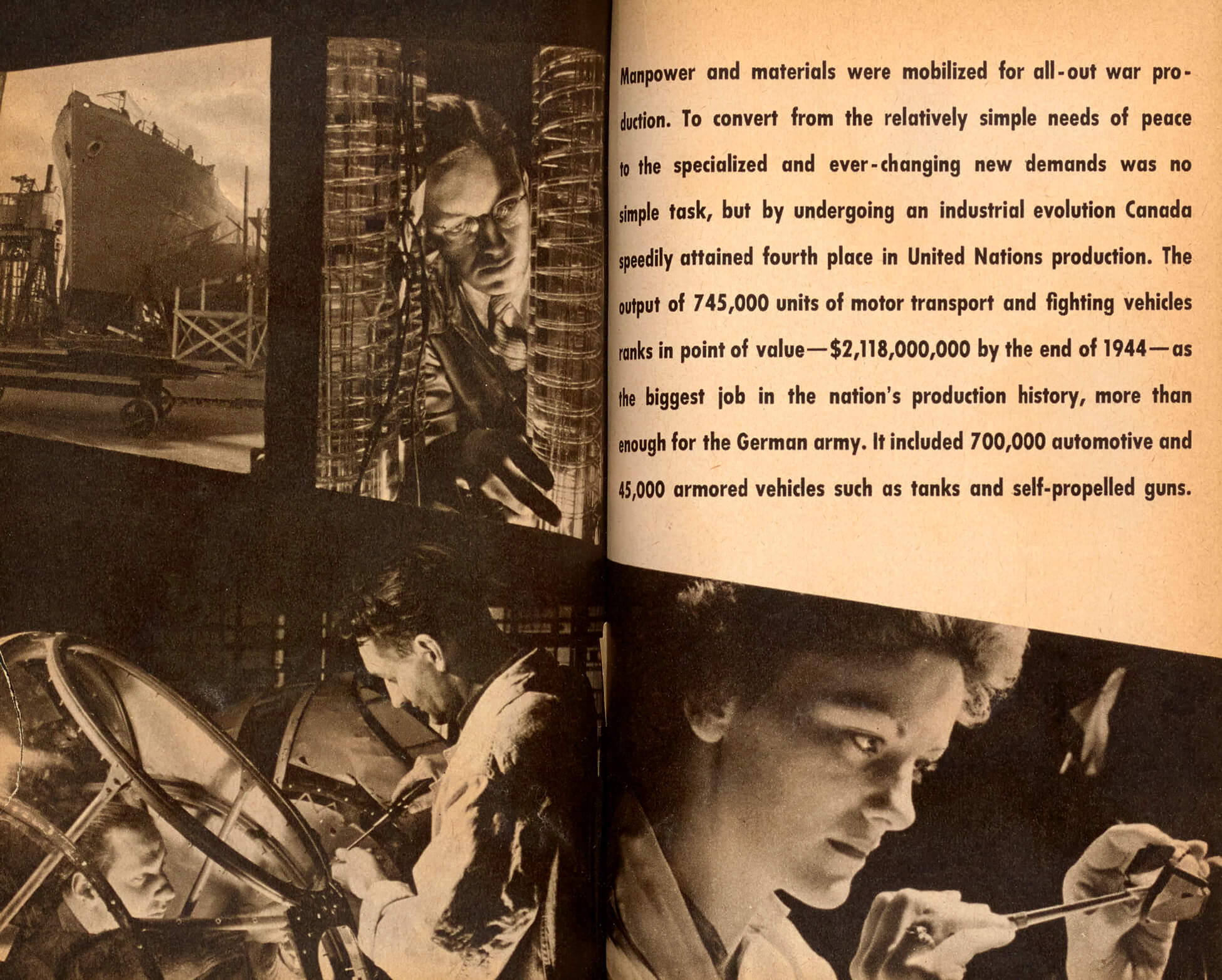

Documentary and photojournalism are closely related as both are generally accepted as realistic representations of the world, and both were mobilized in nation building. The documentary genre became popular in the 1930s and 1940s when the first director of the National Film Board of Canada (NFB), John Grierson (1898–1972), embraced film and photography as a means of unifying the nation. Grierson believed in the power of the collective and considered documentary a means for telling human stories with a social message. Under Grierson’s direction, the NFB Still Photography Division created an idealized image of Canadian life that influenced concepts of nationhood.

NFB documentary photography flourished prior to and during the Second World War, when the Still Photography Division served as the country’s official photo agency. In association with the Wartime Information Board (WIB), the Still Photography Division produced and distributed thousands of photographs in mainstream newspapers and magazines, as well as in its own journal, Canada at War. These photographs highlighted the country’s wartime manufacturing industries, including aluminum and steel, armaments and munitions, shipbuilding, and the production of military clothing and vehicles. After the war, the agency turned from industry to other subjects and themes, but its photo stories continued to shape the image of the nation.

When illustrated magazines were at their peak in the 1950s and early 1960s, photo stories contributed to the image of Canada as a stable and prosperous nation. The NFB Still Photography Division continued to play a central role in both documentary and photojournalism, especially between 1955 and 1969, when the agency supplied hundreds of ready-to-use photo stories to newspapers and magazines in Canada and abroad. Staff photographers Chris Lund (1923–1983) and Gar Lunney (1920–2016) carried out the agency’s mission, and freelance photographers, including Rosemary Gilliat Eaton (1919–2004), Ted Grant (1929–2020), Richard Harrington (1911–2005), George Hunter, and Sam Tata (1911–2005) were also hired on assignment.

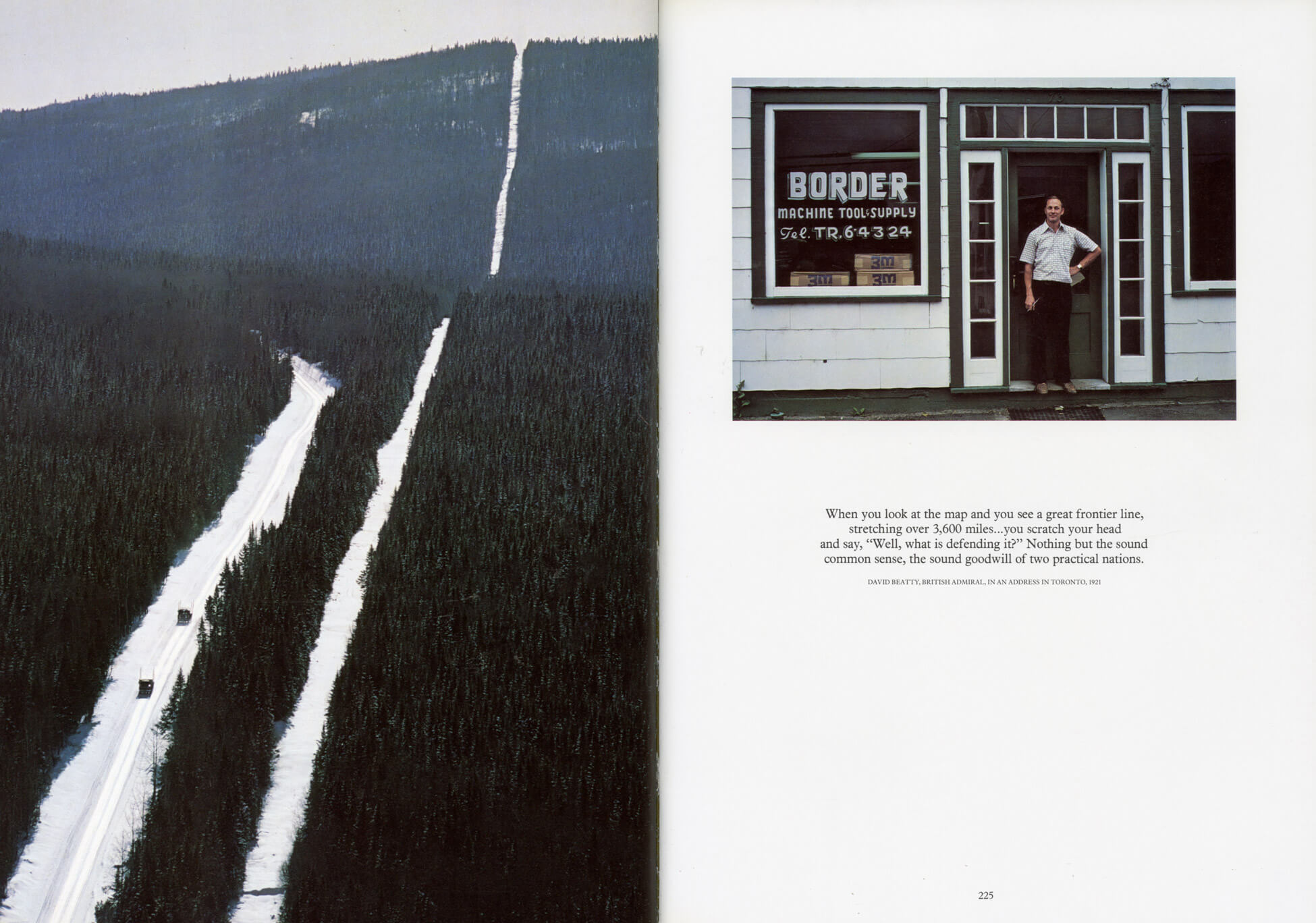

Many stories from this period portray the country’s natural resources, using landscape imagery to signify economic prosperity. A major undertaking in the 1970s was Between Friends / Entre Amis, a bicentennial celebration of the American Declaration of Independence in the form of a book that Canada presented to U.S. President Gerald Ford, and an exhibition displayed in Canadian and American cities in 1976. For this project, twenty-seven photographers working under the direction of Lorraine Monk produced a photographic survey of the Canada-U.S. border.

During this period, many newspapers published inserts that mimicked the format of the illustrated magazines and featured longer photographic stories. The Weekend Magazine, one of the nation’s most popular weekly supplements, turned to colour photography to convey a concept of multicultural nationalism. However, not all of the documentary photo stories published during this era were understood as presenting a positive or celebratory picture of Canada. In 1972, a group of young photographers including Claire Beaugrand-Champagne (b.1948) and Michel Campeau (b.1948) received a grant to spend several months living and working in the rural community of Disraeli, Quebec. When the resulting photographs were published in the Quebec press, they generated a critical backlash for presenting a “miserabilist” view of the community and initiated a conversation about ethics and power in photography.

In the 1970s and 1980s, photojournalism continued to shape popular opinion. Press photography influenced the public perception of prominent figures, and it was used to tell the stories of underrepresented Canadians. Pierre Elliott Trudeau, who served as prime minister from 1968 to 1979 and 1980 to 1984, was a charismatic politician who was aware of the importance of photographs in shaping his image. An award-winning photograph of the prime minister with a young Justin Trudeau tucked under his arm taken by Rod MacIvor (b.1946) fostered a public image of the politician as a family man, while a photograph of Pierre Trudeau welcoming the Troeung family, refugees from Cambodia, taken by Murray Mosher (b.1945) presented an image of humanitarianism.

In the 1970s and 1980s Canadians from diverse backgrounds started to tell their own stories in the press. Toronto’s LGBT magazine, The Body Politic (1971–87) published photographs by journalist Gerald Hannon (1944–2022) that documented and celebrated the gay community. The Black-owned newspapers Contrast and Share News, and the magazine Spear, published the work of Black photographers including Jules Elder, Eddie Grant, Diane Liverpool (b.1958), Al Peabody, and James Russell (b.1946). Their images celebrated the accomplishments of members of the Black community and portrayed events that were not represented in the mainstream press. But no matter the news story, photojournalism played an important role both in shaping communities and in relaying current events through photographs.

From Ethnographic Studies to Decolonizing Photography

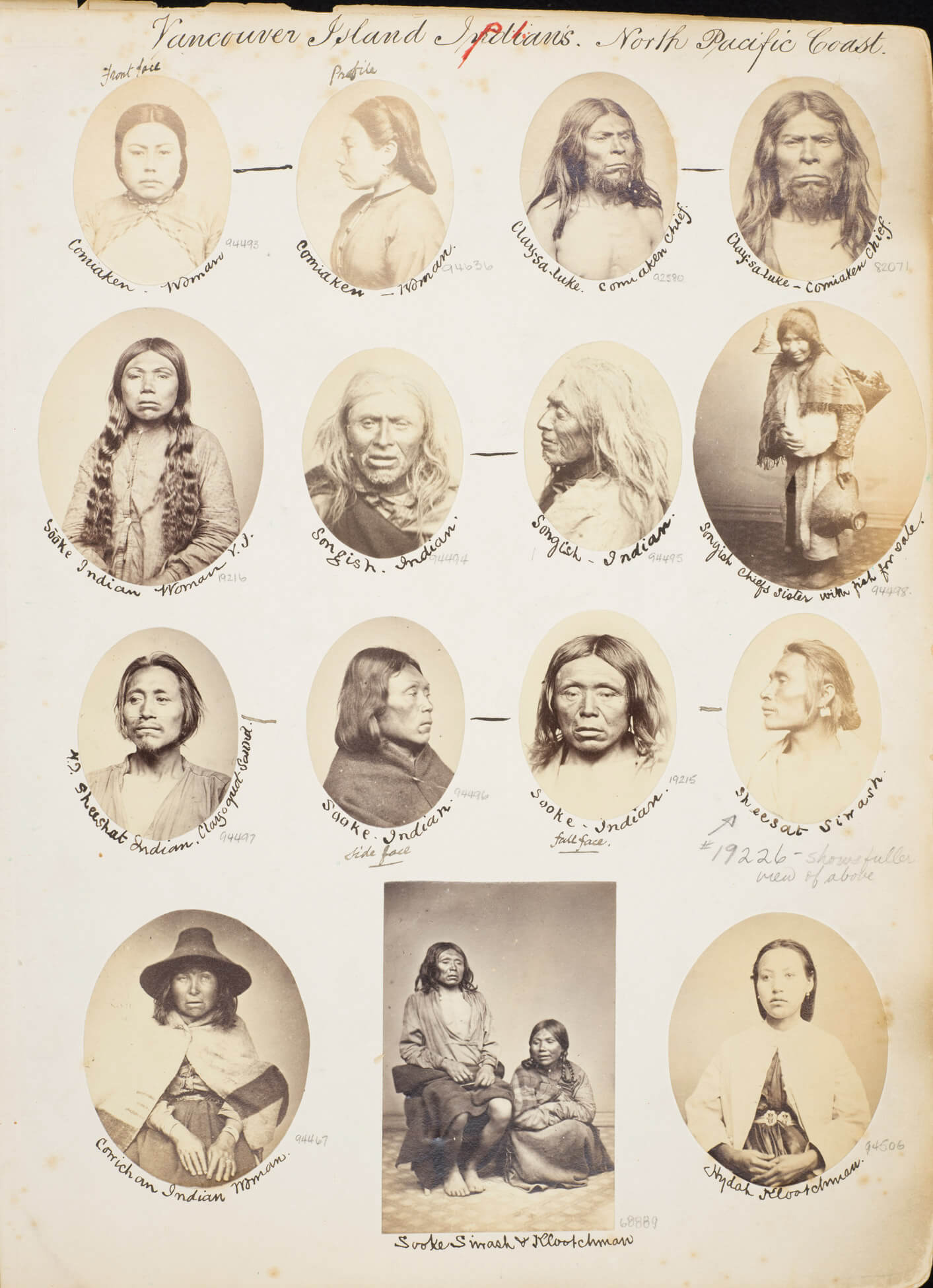

In 1866, photographer Frederick Dally (1838–1914) accompanied a diplomatic expedition to First Nations on Vancouver Island and produced a large collection of portraits, which he marketed as cartes-de-visite. When he closed his business to move to the U.S., many of his negatives of First Nations subjects went to Hannah Maynard, who continued to sell these images for years to come. This commodification of images of Indigenous life in the late nineteenth century is connected to the growth of organized tourism and the emergence of the discipline of anthropology.

Commercial photographers, missionaries, amateur ethnographers, and travellers all photographed Indigenous subjects, sometimes in the name of science, but also for personal use and to advance economic interests and political or religious agendas. In the late nineteenth century, photographers on government expeditions recorded aspects of Indigenous lives that were used in attempts to establish control over land, resources, and peoples. An early example is the photographs of Humphrey Lloyd Hime (1833–1903) for the 1858 Assiniboine and Saskatchewan Exploring Expedition. While they were on inspection tours at the behest of the Department of Indian Affairs, government officials gathered demographic data and assessed whether Indigenous communities were likely to resist the government development initiatives. Meanwhile, commercial photographers such as Edward Dossetter (1843–1919) were specifically hired to make ethnographic portraits during these excursions. These typological studies circulated in various ways, including in government reports, personal albums, and travel literature, and were widely available from 1860 until the early twentieth century.

As a genre, ethnographic photography was used to present an idea of Indigenous biological inferiority in an attempt to justify the political and economic interests of settler colonialism. Colonialism is rooted in a belief that there are biological differences between races, but science has proven that there is no genetic basis for this. This means that race is a social construct. Although the ideology of race developed before the invention of photography, ideas about racial hierarchy were incorporated into European thought through the newly formed social sciences of ethnography and anthropology in the mid-nineteenth century. Ethnographers such as Charles Marius Barbeau (1883–1969) used photography in their fieldwork to document the material culture and customs of people who were thought to be biologically inferior, and photographs were considered evidence to support pre-existing ideas about a racial hierarchy.

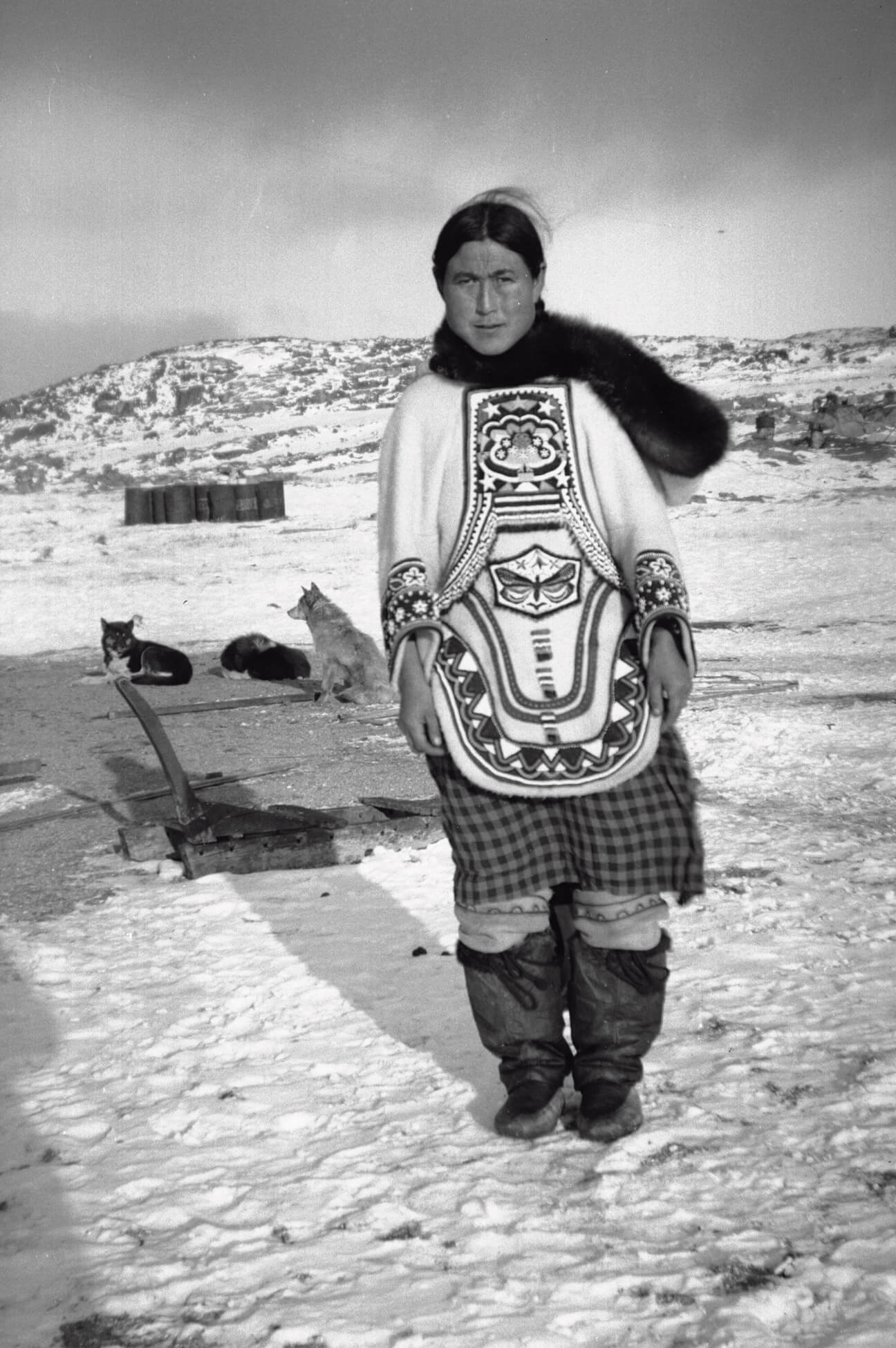

However, even within the oppressive context of settler colonialism, numerous Indigenous photographers resisted the ethnographic perspective that informed mainstream culture. Peter Pitseolak (1902–1973), for example, took up the camera to document traditional Inuit culture and the modernization in his community at the same time the Canadian government was using ethnographic photography to lay claim to the north. Later, Pitseolak’s grandson, Jimmy Manning (b. 1951), turned to photography to portray life in his community of Kinngait, Nunavut.

Photography, like other forms of creative expression, also offered a way for Indigenous practitioners to connect with family and build community. Tlingit photographer George Johnston (1894–1972), for instance, revealed continuities between the past and present in his photographs of everyday life, creating a kind of “extended family album.” For James Patrick Brady (1908–1967), photography was embedded in political activism and his quest for Métis revitalization, while portraits of Elders by Murray McKenzie (1927–2007) brought people together by creating links between generations. James Jerome (1949–1979), a Gwich’in photographer working in the Northwest Territories in the 1970s, also documented traditional activities and made portraits of Dene Elders in the Mackenzie Valley. These practitioners integrated photography into their daily lives and used it as a new way to tell their own stories.

During the 1970s, many Indigenous people and communities across Canada were invigorated by a growing political awareness, and numerous artists turned to photography to portray their own experiences and redefine their images. The 1980s were an important period for Indigenous art and activism, as First Nations, Inuit, and Métis artists, curators, and critics attempted to address systemic racism by gaining access to mainstream cultural institutions. In 1985, a group of photographers founded the Native Indian / Inuit Photographers’ Association (NIIPA) in Hamilton. NIIPA offered training and organized conferences and exhibitions. From the beginning, the association was led by Indigenous women and was committed to gender equality.

At a time when Indigenous people were often pictured according to derogatory stereotypes, photographers turned to image-making as a positive form of self-representation and to reaffirm their cultural identity. Photographs by Dorothy Chocolate (b.1959), for example, depict people in her community of Gamèti (formerly Rae Lakes) practising traditional skills and living off the land. Many of the photographers affiliated with NIIPA, including Jeff Thomas (b.1956), Shelley Niro (b.1954), and Greg Staats (Skarù:ręˀ [Tuscarora] / Kanien’kehá:ka [Mohawk] Hodinöhsö:ni’, Six Nations of the Grand River Territory, Ontario, b.1963), have resisted the objectifying gaze of ethnographic photography and have contributed a great deal to the decolonization process by restoring Indigenous perspectives.

Photography in Advertising and Commodity Culture

Commercial photographers were the first to explore the potential of photography as a commodity, and many studios, including the Livernois Studio in Quebec City, offered their clients collectible portraits of prominent figures, such as this cabinet card, c.1874–81, of Charles-Félix Cazeau, a French Canadian priest and the administrator of the Catholic Archdiocese of Quebec, as a way of increasing business. Technical developments in the 1880s greatly improved the ease and speed of photography and advanced its integration into capitalist culture, and the widespread use of the halftone printing process in the 1890s furthered these connections by allowing for quick and inexpensive reproductions.

In the early twentieth century, governments and corporations in Canada embraced photography for their marketing campaigns. Advertising and related forms of commercial photography adapted existing photographic styles and genres to commodity culture because, unlike other types of photography, advertising photography does not have distinctive features. Instead, as media theorist Anandi Ramamurthy explains, this genre is best characterized by the way it “borrows from and mimics every existing genre of photographic and cultural practice to enhance and alter the meaning of lifeless objects” as commodities.

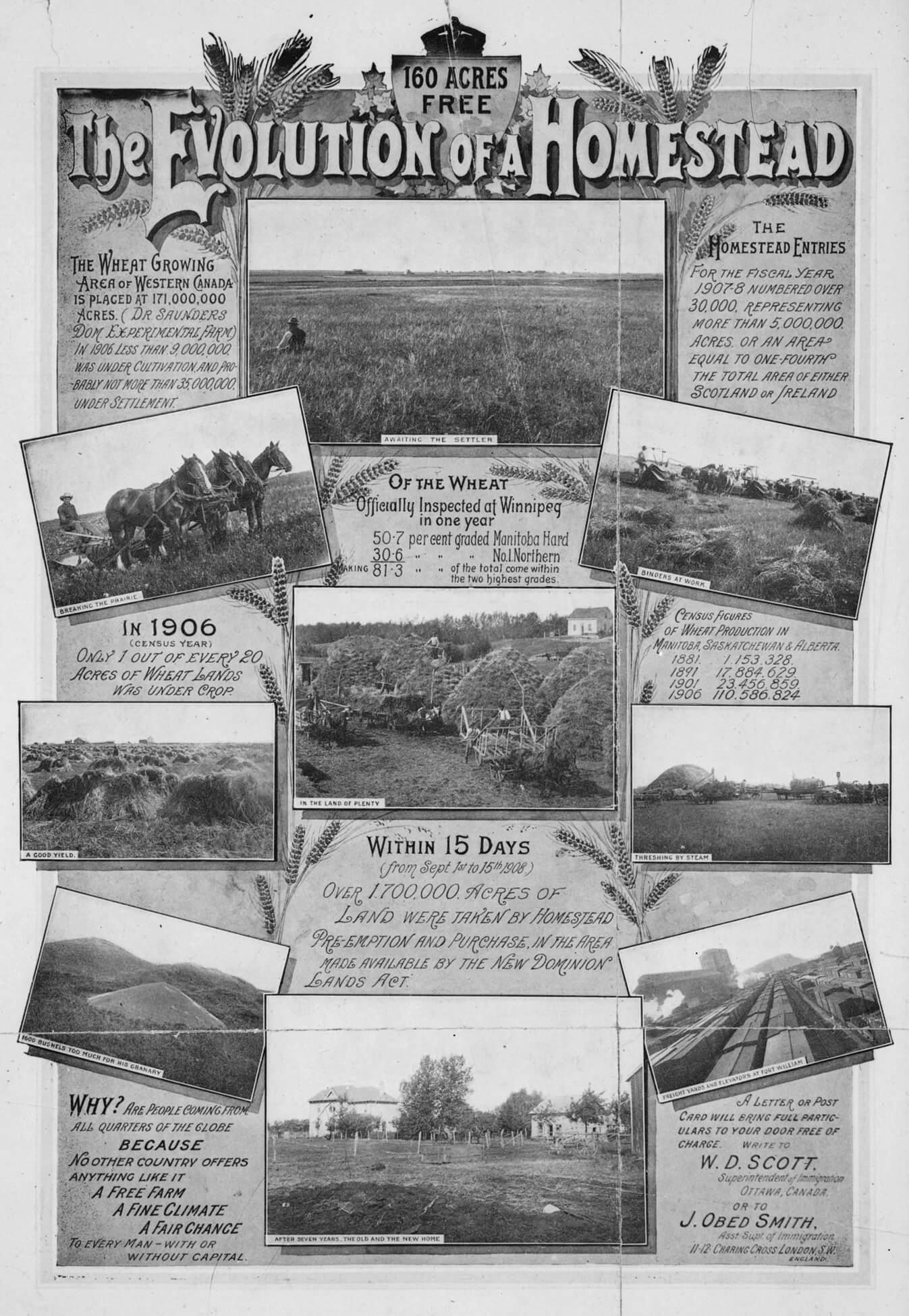

In Canada, early advertising photography promoted the nation through representations of landscape. In the 1890s, government branches, such as the Department of Agriculture and the Department of the Interior, began using photographs to market Canadian farm products, as well as to promote the country to potential settlers. Emigration agents adopted a range of methods to publicize the attractions of Canada and played a critical role in dispelling negative perceptions about the country overseas. Posters, pamphlets, newspaper advertisements, and public lectures illustrated with lantern slides were used to create a positive impression of Canada in Britain.

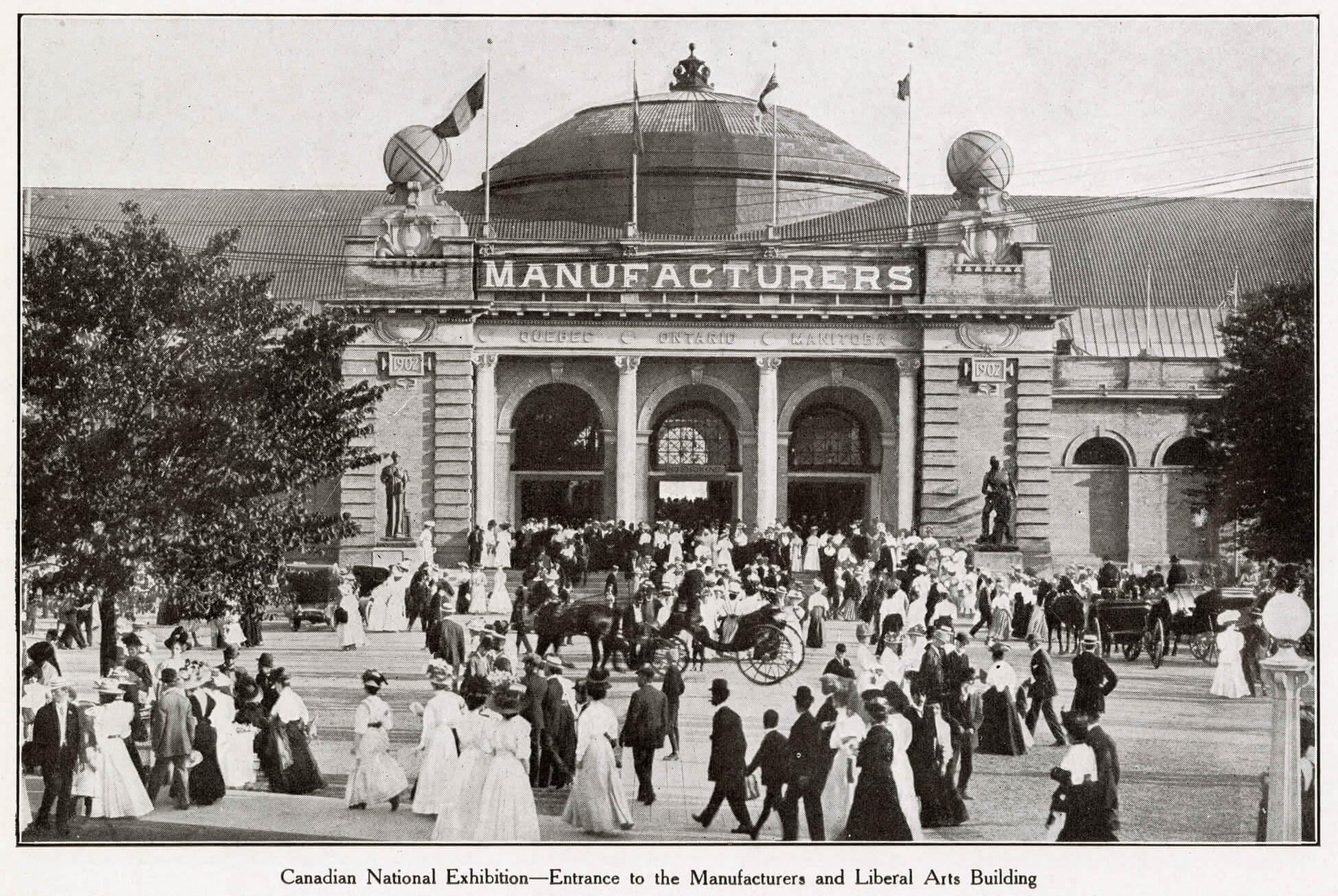

In 1911, Robert Rogers, the Minister of the Interior, described the country’s immigration policy as “in the first instance simply an advertising policy—a means of placing the advantages of Canada before such people in other countries as we desire to induce to come to Canada.” In the Prairie provinces, agriculture departments acquired photographs of harvest scenes from commercial photographers to attract farmers to the region. Similar strategies were used by municipalities in the early twentieth century as they sought to encourage commerce. Many guidebooks and souvenir booklets of Toronto showed scenes of wide, tree-lined streets with large houses, civic buildings, schools, and recreational activities. These photographically illustrated guidebooks introduced key features of the city as a means of promoting travel and business.

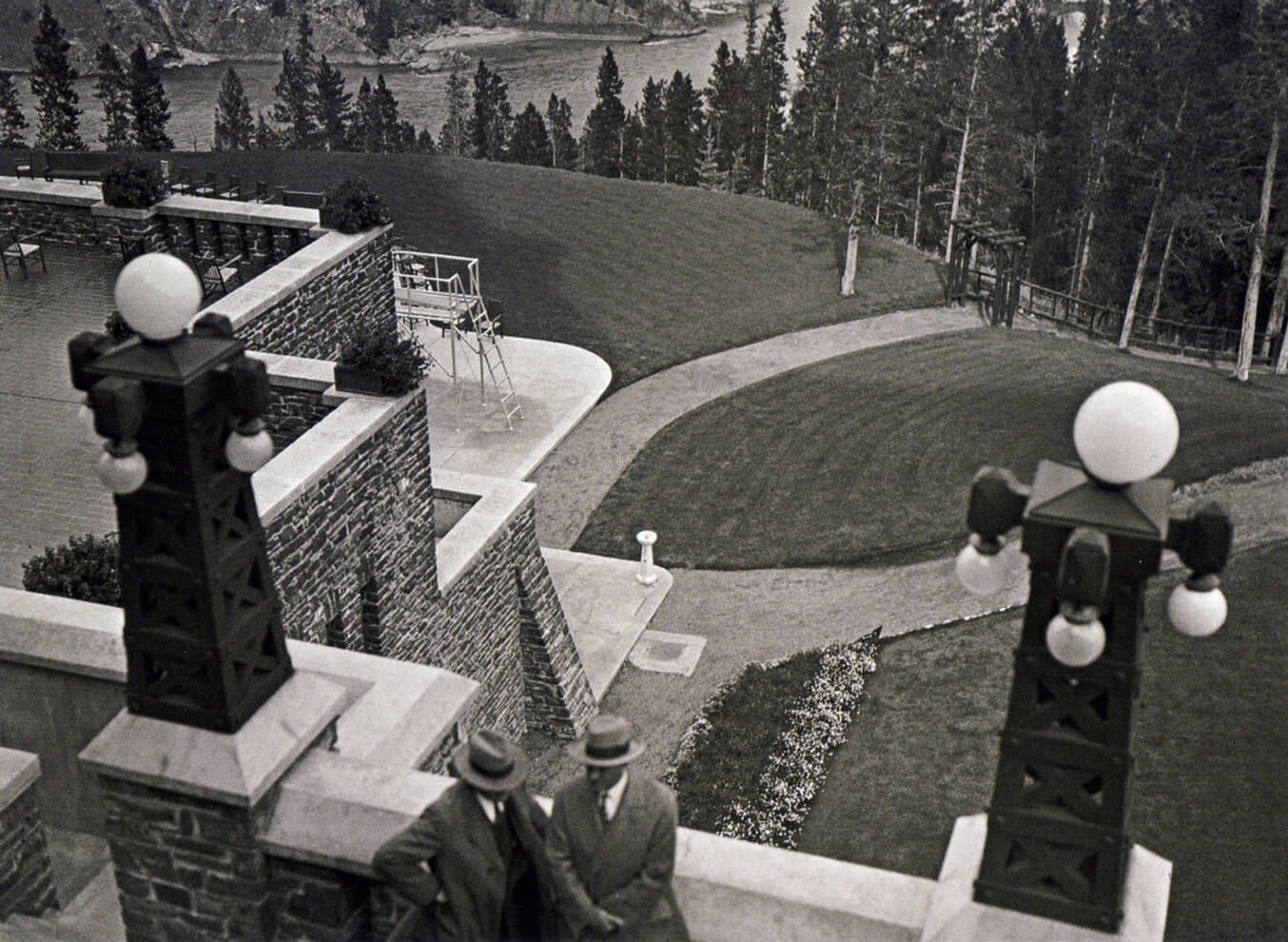

Corporate advertising overlapped with nation building in the 1910s and 1920s as the Canadian National Railways and Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) launched wide-ranging publicity campaigns. Both companies hired photographers to create scenic views that would promote settlement and tourism. The CPR’s publicity department sought to construct an idea of the nation as rooted in the soil and then to associate the land with the company. Minna Keene (1861–1943) and her daughter Violet Keene Perinchief (1893–1987) contributed to the CPR’s marketing campaign by taking photographs in the Rockies for nearly four months during the summer of 1914. Their images are modelled on traditional landscape paintings and seek to associate the splendors of nature with the transcontinental railway. John Vanderpant also received a commission from the CPR in 1929. However, instead of wilderness scenery, his photographs emphasize progress through modern, often abstract renderings of CPR hotels and other aspects of the built environment, as seen in his View, taken from the hotel, of the exterior walls, lamps and grounds of the Banff Springs Hotel, 1930.

The 1920s was the era of big business, expanded production, and newly standardized systems of management, and advertising photography flourished. In this context, corporate advertising was designed to stimulate demand for a wide variety of newly available products. Photography became popular in advertising, almost replacing illustration over the course of the decade. Advertising agencies, informed by advances in psychology, began to produce ads that appealed to the emotions and desires of consumers.

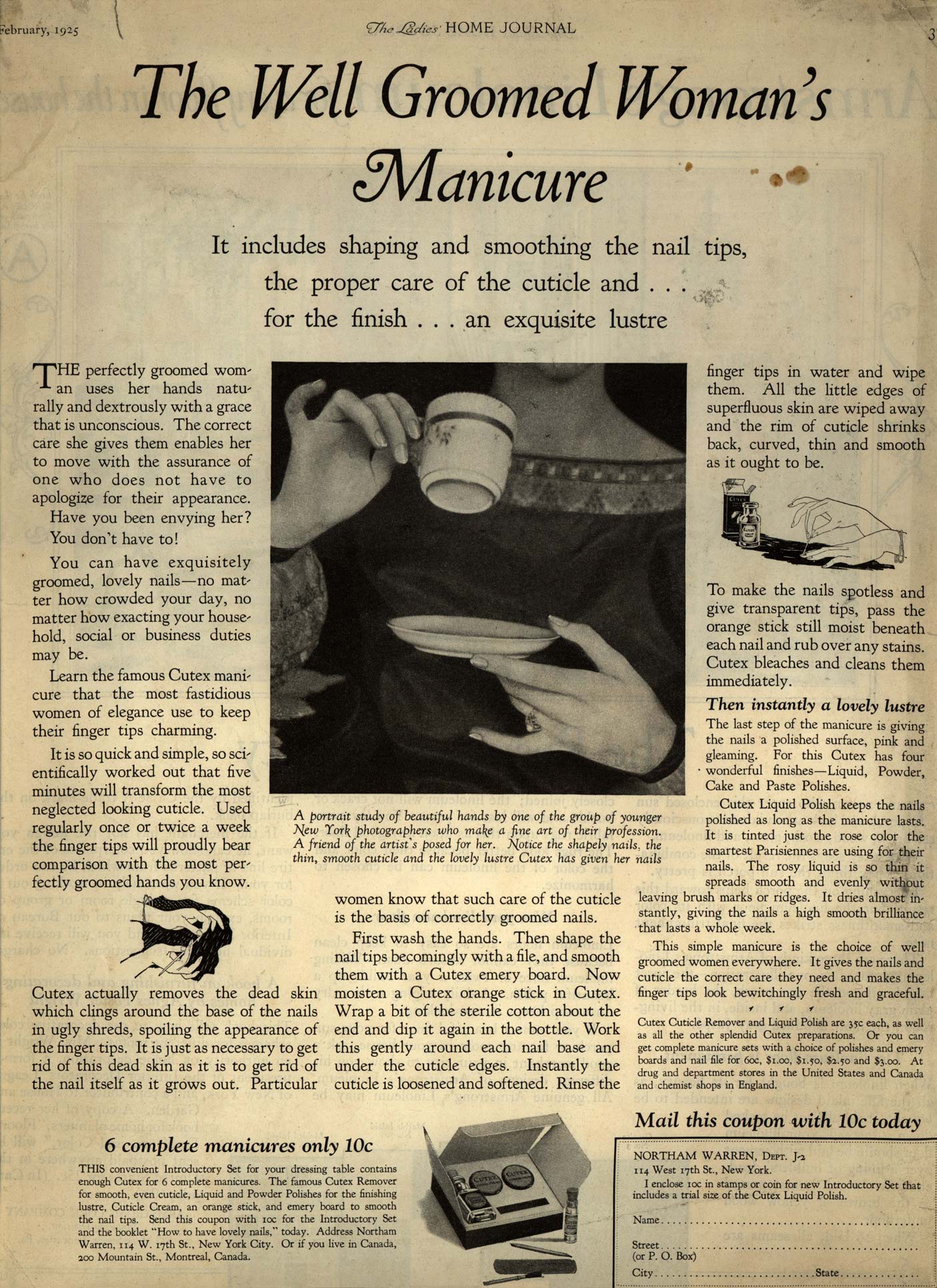

Although the commercial realm was not exempt from the gender discrimination that plagued other fields of photography, there were some opportunities for women. Likely because they were also targeted as consumers, women were considered well suited to work in the field. Margaret Watkins was a trailblazer who adapted the style and motifs of her domestic still lifes for modern advertising. In her work for Macy’s department store and the J. Walter Thompson ad agency, she emphasized sensuous elements to convey luxury and pleasure. In an ad for Cutex, she photographed a woman’s elegant hands holding a teacup. Although the product advertised is a manicure set, what sells the commodity is the idea of a well-groomed woman. Watkins understood that ads could attract consumers through the allure of an image and a concept rather than by calling attention to the product.

Over the next several decades, numerous photographers adapted stylistic features from portraiture and art for the world of advertising as they represented concepts and emotions that would make products and services appealing to consumers. Fast, made in the 1930s by Brodie Whitelaw (1910–1995), integrated his understanding of geometric form, which he first explored in his artistic works, into his commercial photography. Yousuf Karsh, who participated in advertising campaigns for companies such as Ford Canada and Atlas Steel in the 1950s, used the characteristic drama of his portraiture to portray factory workers in a heroic light. These industrial portraits were printed in company brochures, annual reports, calendars, and international magazines. Some were exhibited in art galleries and other venues, and they were described as capturing “the spirit and romance of the automotive industry.”

In the 1950s and 1960s, Montreal-based photographer June Sauer (b.1924) worked on fashion shoots for high-end department stores including Ogilvy’s and Holt Renfrew. She brought a playful sensibility to her work, using and naturalizing mainstream constructs of gender and sexuality to sell outfits. In the 1980s, contemporary artists including Vikky Alexander, Ian Wallace (b.1943), and Ken Lum brought a critical eye to consumer culture. Appropriating images and techniques from commercial photography, they investigate the mechanisms of advertising in their artwork.

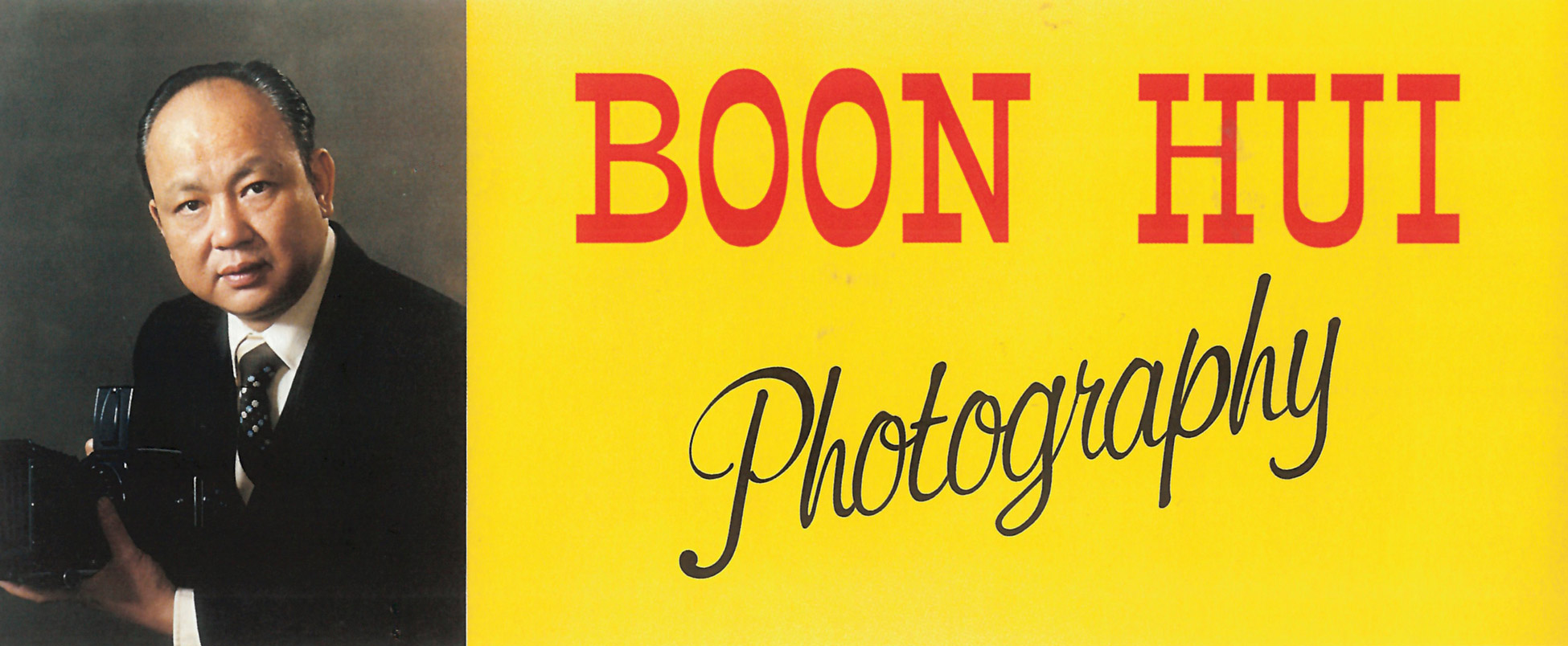

Lum’s Portrait Attributes series (1987–91) pairs portraits with signage reminiscent of billboard advertising, drawing attention to the tropes that have defined commercial photography. In one image from that series, Boon Hui, 1987, Lum paid homage to the studio photographer who taught him how to use a camera. Lum’s work and other artistic interventions show how commercial photography relies on stereotypes and predictability, rather than on the uniqueness that defines contemporary art. There is a certain irony in the postmodern artists’ critique of advertising photography coming to pass at the same moment that the high-end art market embraced photography.

About the Authors

About the Authors

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements