Paul Kane’s career spanned more than twenty years, during which his artistic vision was focused on subject matter rather than technical development. It is the subject matter of his work that has guaranteed his place in Canada’s art history. Kane wrote nothing about his aesthetic beliefs or technique, and there is no indication that he reflected theoretically on his artmaking. Information about his technique and style resides mainly in the artworks he produced.

Early Years

Aside from his presumed early private tutelage with Thomas Drury, the drawing master at Upper Canada College, Kane’s study of art was largely self-directed. His two main modes of learning were by copying prints and paintings, and by drawing from nature. Copying painted portraits by European masters figured largely in his development, not surprising since Kane embraced portraiture as his primary source of artistic income. But his copy work also included landscapes, and given Kane’s later original production, one can assume his early models were the picturesque and the sublime. His studies from nature included some life drawing (though never nudes) and landscapes, and he also depicted sculpture, furniture, and architecture.

Ultimately Kane’s focus as an artist was on Aboriginal culture: the individuals, their customs, and the landscape of the territories where they lived. He intended to create a cycle of large studio paintings documenting the peoples and the landscape of Canada’s West. By the time he embarked on his mission, the three pillars of his technique and artistic approach were in place: the observation of nature, the aesthetic of the picturesque, and the conceptual conventions of Romanticism. All three approaches informed not only his finished oil paintings but also his sketches, though the sketches were primarily practical.

Romanticism

If one overarching descriptor were attached to Kane’s approach, it would have to be Romantic. However, given that Kane left no words on his personal theory of artmaking, it is difficult to ascertain the exact nature of his approach. Is the Romanticism evident in his cycle of finished oil paintings, and to a lesser extent in his field sketches, indicative of a conscious desire to portray a “vanishing race” in a way that would satisfy the aesthetic expectations of his prospective patrons? Or was it simply the result of his exposure to the Romantic style through his European travels and the widely available engraved or lithographic reproductions of the time?

Kane’s Romanticism is most pronounced in his oils on canvas, such as A Prairie on Fire, c. 1849–56. Many of the oils embody conventions of Romantic painting: the tableau-like, staged compositions; the dramatic, moody skies; the diffuse, murky tonalities; the spectacular light effects (generated by natural phenomena, either witnessed or imagined by Kane); the sublime or picturesque views; and the idealization of the individuals who were his subjects.

Conceptually Romanticism is most notable in Kane’s choice of subject: Aboriginal life, as embodied in the “exotic,” the “primitive,” and the relationship of both to nature. While the pictorial effects of the finished works speak to the artist’s feelings of loss and drama—as can be seen in The Man That Always Rides, c. 1849–56—Kane’s attempts to immortalize his Aboriginal subjects in a heroic mode have the paradoxical effect of erasing the artistic empathy that is evident in the subjects’ vitality and character in the original sketches. Yet these pictorial effects are essential to Kane’s work. They function as mechanisms that create a distance between the painted subject and the urban viewer. Romanticism, it can be argued, allowed its intended audience to experience an objective, voyeuristic fascination with the exoticism of “Indians” and their way of life without feeling any personal connection that might raise questions about the white man’s role in their predicted disappearance. This notion is evident in works such as Kane’s The Constant Sky, c. 1849–56.

Preliminary Works

Kane approached his program methodically by following the processes advocated by the European academies of art. Oil paintings were based on sketches and pictorial concepts either drawn from life or developed in the studio. Most of them are on paper, which is not unusual; paper is also especially well suited for transport.

These works vary in medium, approach, and function. Whether they were executed in graphite, watercolour, oil, or some combination thereof, Kane drew either loosely and rapidly or with careful attention to detail, depending on what circumstances allowed and what the impetus was for a particular sketch. Since conditions in the field were unlikely to have been optimal, some of the “life drawings” were probably done after the fact—for instance, in a makeshift studio at the local Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) post while he waited for travel to resume.

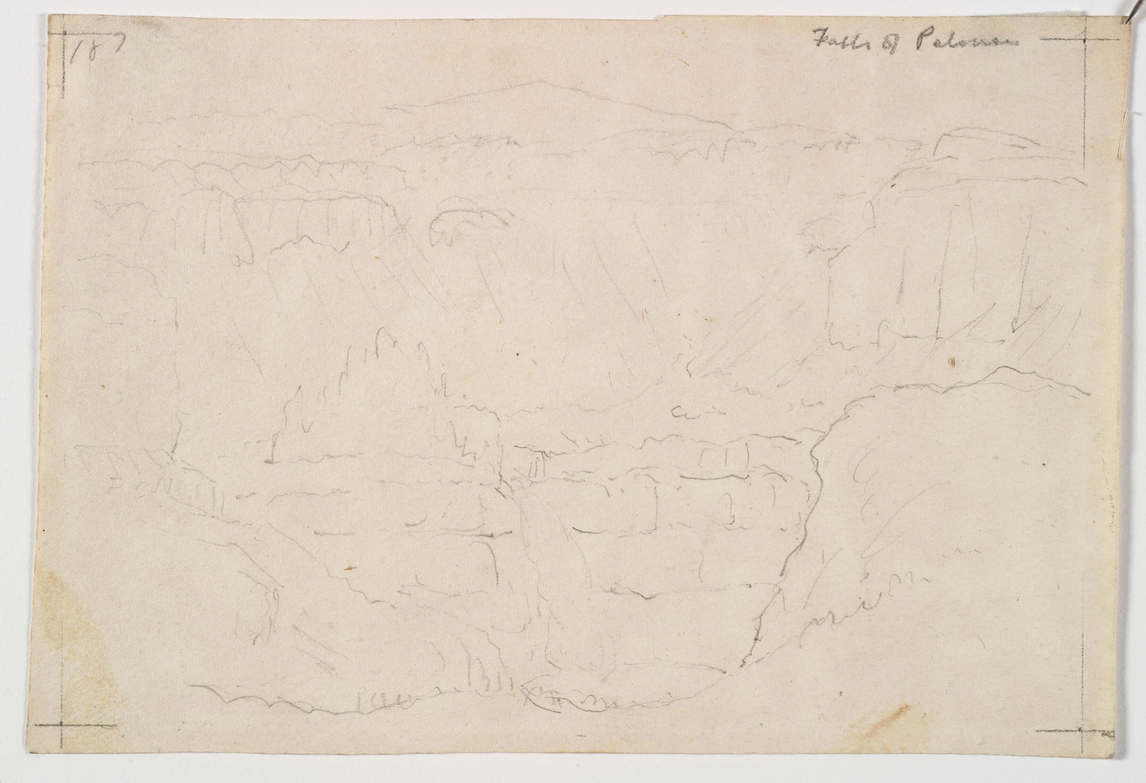

This extent of Kane’s preparation is evident in his various images of the lower Pelouse Falls, a site he visited in July 1847 and noted in his journal. In Lower Falls on the Pelouse River, 1847, Kane offers a highly articulated view in graphite and watercolour, his vantage point being a short distance up the northwest bank of the river, allowing for a focus on the waterfall and the spectacular craggy rock formation. The judiciously applied watercolour suggests the colours found in nature.

Falls of Pelouse, 1847, reveals that Kane ascended the bank that offered a sweeping view east, beyond the falls to a distant mountain range. Working in graphite only, Kane gives but general lines of the various elements of the landscape, as if he were trying to assess the compositional potential of this particular vantage point. However, it is his detailed drawing (with its hints of watercolour) that is obviously the basis for his highly worked-up oil-on-paper rendition, Lower Falls on the Pelouse River. The latter, possibly intended as both a finished work and the model for his large oil on canvas, would have unquestionably been painted in his studio rather than en plein air.

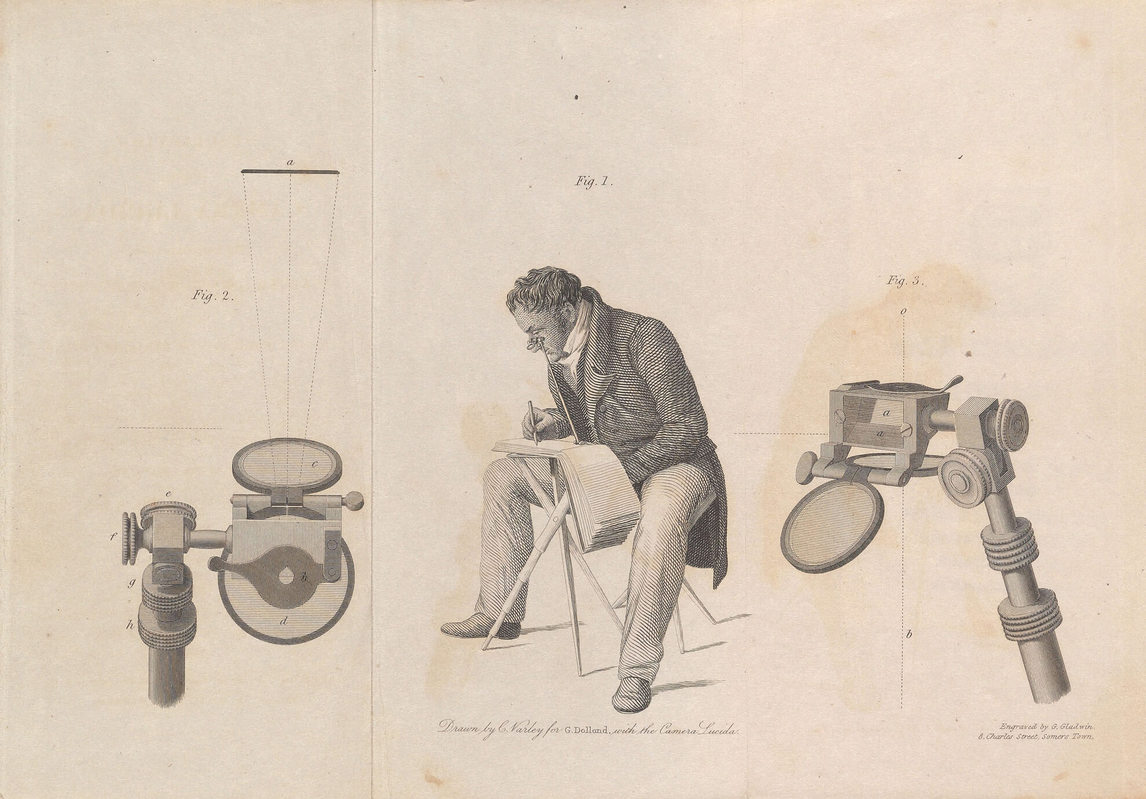

Sketches and the Camera Lucida

The disparity in perspective among Kane’s drawings is striking. Pictorial hints within some of his more accurately rendered drawings strongly suggest that for these he used a camera lucida, an optical instrument much favoured by artists since its invention in the early nineteenth century. It was often carried on expeditions to document the topography of a landscape (usually geological formations) and its inhabitants, in preparation for lithographic illustrations in exploration publications. Small and portable, the camera lucida is essentially a prism atop an extendable stem. The artist chooses a subject or scene, views it through the prism, and simultaneously sees an image of the actual scene projected onto a sheet of paper below; the adjustable stem makes the subject larger or smaller. Once the subject is decided upon, the artist can “frame” it within the sheet, trace the lines, and shade in tonalities as desired.

Lower Falls on the Pelouse River is suggestive of the use of a camera lucida. Kane records the general broader masses of the landscape but also highlights the lines to articulate a detailed sense of the geological forms and stratifications. The pressured notational marks that articulate the strata of the rock face function as register marks, ensuring Kane could properly realign the view and projected image should he have inadvertently shifted focus. The marks also functioned as a way for Kane to showcase essential elements of the landscape.

Truth and Accuracy

Kane embraced the idea that his work be perceived as “truthful” and “accurate.” Imitating the successful strategy of the American artist George Catlin (1796–1872), Kane solicited testimonials from people familiar with the subjects he had depicted. Certificates confirming the masterful qualities of Kane’s sketches were issued by Hudson’s Bay Company factors in the Columbia River region, all of whom were well acquainted with the area. The testimonial of John Lee Lewes of Fort Colville in the Oregon Territory is a prime example: “The sketches which Mr. Kane has taken, representing Indian Groups are most true and striking, their manners and customs are depicted with a correctness, that none but a Master hand could accomplish. The individual likenesses are also of a first rate class … most striking and perfect likenesses…. The Landscape Scenery … also most correctly delineated, and from their truth to nature … convey a Just Idea of the many Picturesque and romantic spots of the Columbia [River].”

Despite Kane’s apparent penchant for dispassionate observation, the aesthetic conventions and contrivances commonly found within the canon of Western art are evident throughout his oeuvre, including his works on paper. Kane uses elevated viewpoints, aerial perspective that leads the viewer’s eye into the distance, asymmetry of the landscape, and a variety of topographic textures within a single image. Even in watercolour drawings or oil sketches that are assumed to have been drawn on the spot, Kane has either actively sought out or modified what nature had to offer, creating views that are picturesque, such as Fort Edmonton, c. 1849–56. And, of course, Kane’s tendency to romanticize and idealize in some of his portraits also derives from aesthetic convention, as in his oil painting Kee-akee-ka-saa-ka-wow, c. 1849–56. Kane’s pictures were inspired as much by learned visual culture as they were by the raw nature that was his subject.

Kane would not have seen his use of aesthetic conventions as contradicting his pursuit of accuracy. For Kane, truth was not necessarily objective verisimilitude, but the transcendence of the particular in order to evoke a more profound essence of his subject.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements