Paul Kane’s legacy is found in the images he created that were based on his travels through Canada’s West, complemented by his travelogue Wanderings of an Artist among the Indians of North America. The range and importance of his field sketches and oil paintings of Aboriginal peoples, their culture, and lands are undeniable. However, this legacy has been understood and appreciated by ethnographers, historians, art historians, and literary critics in remarkably different ways.

Illustrating an Unknown Country

Kane was the first and only artist in Canada to embark upon a pictorial and literary project featuring the country’s Aboriginal peoples, using the medium of portraiture in a time before the dominance of photography. Kane was working within a model initiated by Swiss artist Karl Bodmer (1809–1893) and American artist George Catlin (1796–1872) and adopted by Americans such as Alfred Jacob Miller (1810–1874), John Mix Stanley (1814–1872), and Seth Eastman (1808–1875), all of whose public profiles were enhanced through exhibition and publication.

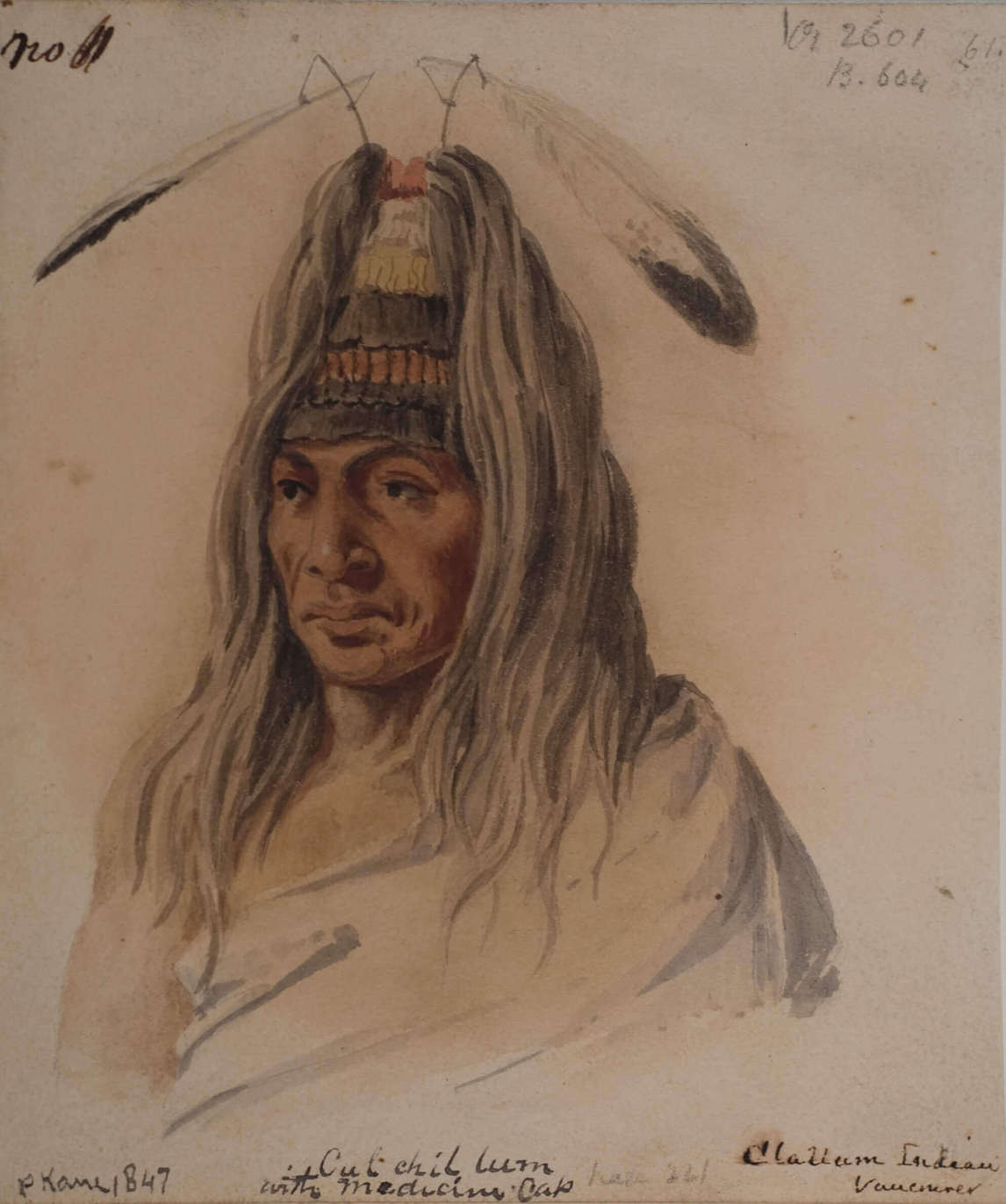

Kane’s objective, according to the preface of his book Wanderings of an Artist among the Indians of North America, was to “sketch pictures of the principal chiefs, and their original costumes, to illustrate their manners and customs, and to represent the scenery of an almost unknown country.” It was a challenge to which he rose, despite the numerous obstacles, such as cultural differences, harsh terrain, and the difficulty of obtaining patronage. During his travels Kane encountered over thirty different tribes, and he painted their vibrant cultural traditions as well as individual portraits.

Kane’s legacy, which documents a unique aspect of Canadian history, is threefold: the hundreds of sketches and drawings; the ensuing cycle of one hundred studio paintings; and the journal he wrote, with its subsequent incarnation as an illustrated book. The works he produced reflect the prevailing attitudes toward Aboriginal peoples held by white society in the mid-nineteenth century. The oil paintings were particularly compelling in the artist’s day because they reinforced the trope of the “noble savage,” a stereotype that was a product of the Western world’s Romantic vision of indigenous people and their ancestral lands, which had been colonized by Europe. Wanderings of an Artist likewise reinforced this attitude. By today’s sensibilities it is the hundreds of sketches that Kane produced that are most compelling. Regarded as fresh and immediate, the sketches are valued as bearers of authenticity, created by an eyewitness with a fine talent for capturing the subject matter before him.

The Salvage Paradigm

Kane’s mission to record the life of Aboriginal peoples of the Northwest has all the hallmarks of what later became known as the salvage paradigm in which a dominant society attempting to save through documentation the culture of another that it considers to be at risk of vanishing. This motivation is particularly clear in George Catlin’s Indian Gallery project, created in direct response to the U.S. government’s agenda to remove the Aboriginal people to reservations. Although Canadian policy was less overt, this idea did have currency in Canada and was mentioned in 1852 in the context of an exhibit of Kane’s paintings. Kane’s attitude seems to have supported the salvage imperative as he accepted the inevitability of the Aboriginal peoples’ demise caused by the relentless encroachment of Western civilization.

Yet a conundrum lies at the heart of Kane’s work. Contemporary critical analysis pegs Kane as an appropriator who profited from picturing the lives of disempowered indigenous peoples, and even as a racist who failed to adequately respect the cultures he encountered and portrayed. However, Kane did make copious detailed and accomplished renderings of individuals and their thriving and vital culture. His work has no photographic parallel, for no one had yet turned a camera on the prairies and beyond. Kane thus built an enduring and valuable primary visual record of a culture that we otherwise would not have.

Field Sketches and Studio Paintings

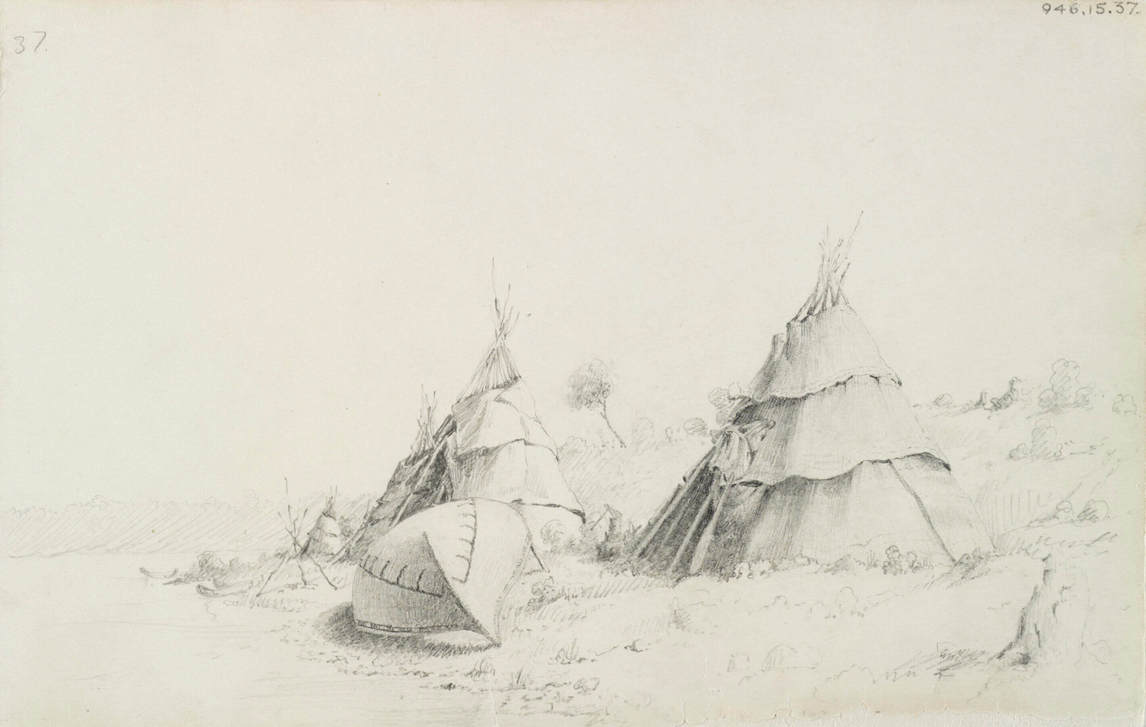

During his travels Kane generated a great quantity of pictorial material—his field sketches. Once he was back in his Toronto studio, these sketches were essential as he developed his cycle of one hundred oil paintings on canvas.

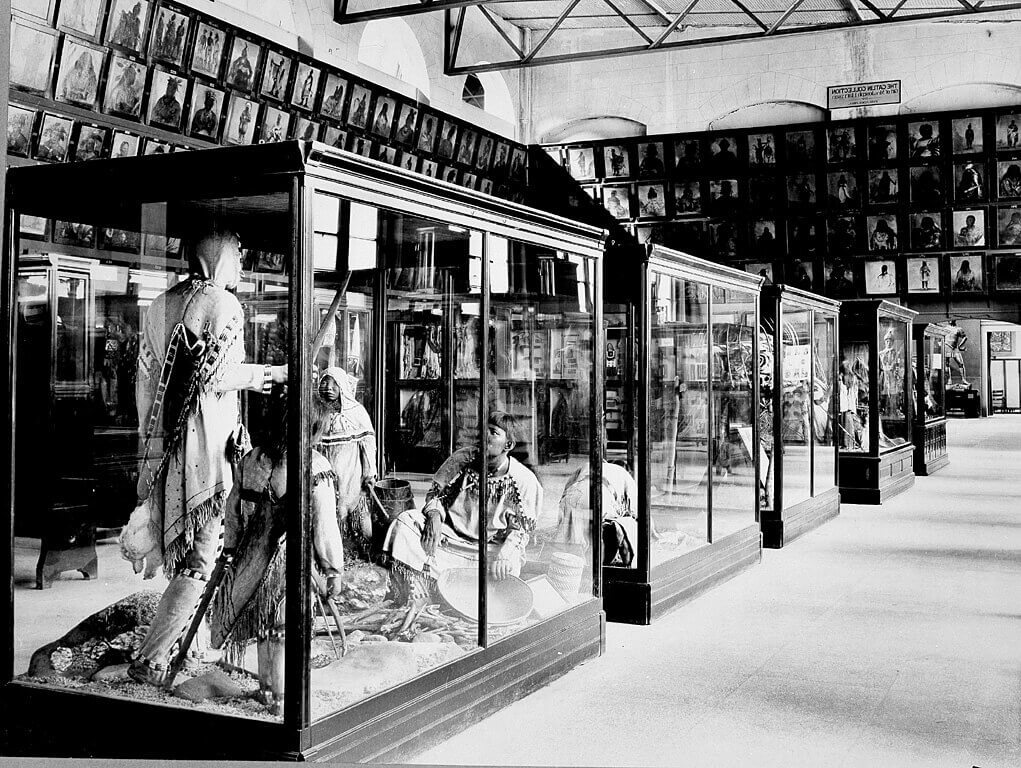

The fieldwork and the studio paintings are often treated as discrete categories within the artist’s “Indian project.” Historically the oil paintings have had a high public profile: the set of one hundred was exhibited in 1904 and was acquired by the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, in 1912. By virtue of their relatively stable medium, the oil paintings have been on display more often than the sketches. The majority of the sketches remained in private hands for over a century, with the exception of one significant group acquired by the ROM in 1946. As works on paper, the sketches are more vulnerable to light degradation and for conservation reasons have been kept in protective storage for extended periods even when they are held by a public institution.

The sketches were generally assumed to have been executed on the spot or, if not directly from life, then close in time and location to their subject—the artist’s goal being to produce an accurate likeness. They have been of particular interest to ethnographers, who assume Kane engaged in dispassionate observation. Art historians view the sketches as fresh and vibrant in comparison to the more laboured and contrived studio paintings. This dual perspective has helped to determine Kane’s creative process and his place within the spectrum of visual culture in Canada. Yet to be addressed by either group of researchers are the differences and nuances in approach, production, and function of various types of sketches; some of them may not be fieldwork at all but rather preparatory studio studies. Additional research will lead to a better understanding of the development of Kane’s cycle of paintings.

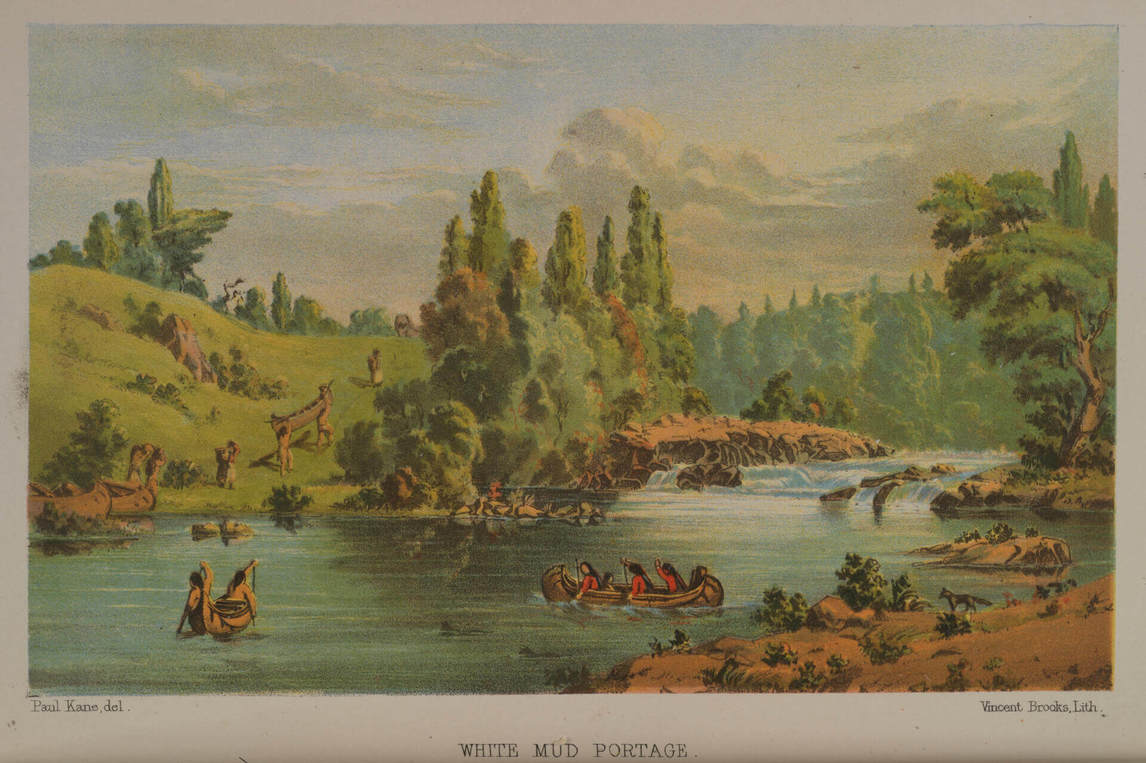

The oil paintings, while based on the sketches, have been recognized by all as unabashedly romanticized images: the landscapes are painted in the tradition of the sublime, and some of Kane’s human subjects are transformed into the “noble savage,” whether through modifications to stance, clothing, or accoutrements or through additions of mood-evocative backgrounds. Some of the paintings, as noted in current ethnological commentary, show blatant ethnographic inaccuracies. Kane’s romanticization of his subjects may be a result of his need to fulfill the stylistic expectations of his client, or it might simply indicate how Kane was a painter of his time. To date, Kane’s reputation has not been affected by the changing evaluation of his artistic strengths or the perceived shortcomings of his works.

The book Wanderings of an Artist among the Indians of North America, based on Kane’s field journal, was published in 1859. A venture inspired by George Catlin’s earlier publication, this fleshed-out account of Kane’s travels was in the making at least as early as 1852, when an exhibit review quotes at length from “Kane’s journal.” Wanderings of an Artist is a hybrid, a travelogue that includes detailed ethnographic descriptions as well as accounts of events not directly experienced by the artist. It is illustrated with twenty-one images, much fewer than Kane had hoped for and far shy of the hundreds of sketches and paintings he made. The eight chromolithographs and thirteen woodcut engravings are based on Kane’s paintings, sketches, or combinations of these.

Wanderings of an Artist is known to have been ghostwritten. Comparisons between the field journal and the published book reveal significant differences in diverse aspects such as content, spelling, and length of text. The text’s anachronistic telling of events belies the authenticity of the author’s experience and highlights the constructed nature of the book’s contents. Moreover, the book’s overt imperialist sensibility—so different from the neutral language and expression found in Kane’s journal—suggests a much different voice from that of Kane.

To what extent then can Wanderings of an Artist be used as a framework in which to assess Kane’s cultural attitudes and his oeuvre? Do we consider Kane complicit in its overt imperialist discourse, if only by association? Or is the ghostwriter’s voice so dominant that we should consider Kane’s artwork distinct from the text of the publication? To date, analysis of Kane has taken a middle ground, by assuming that his pictorial oeuvre—his preliminary works and finished paintings—was the tangible basis if not for the entire text then for a significant part of it. This gives the text some credibility despite its huge departures from Kane’s original journal.

The Mystery of the Copies

The set of one hundred oils on canvas executed for Kane’s patron, George W. Allan, and delivered in 1856, is considered the core of Kane’s painted output. However, additional versions of some of the paintings exist—in most cases just one copy but in some cases two or even three.

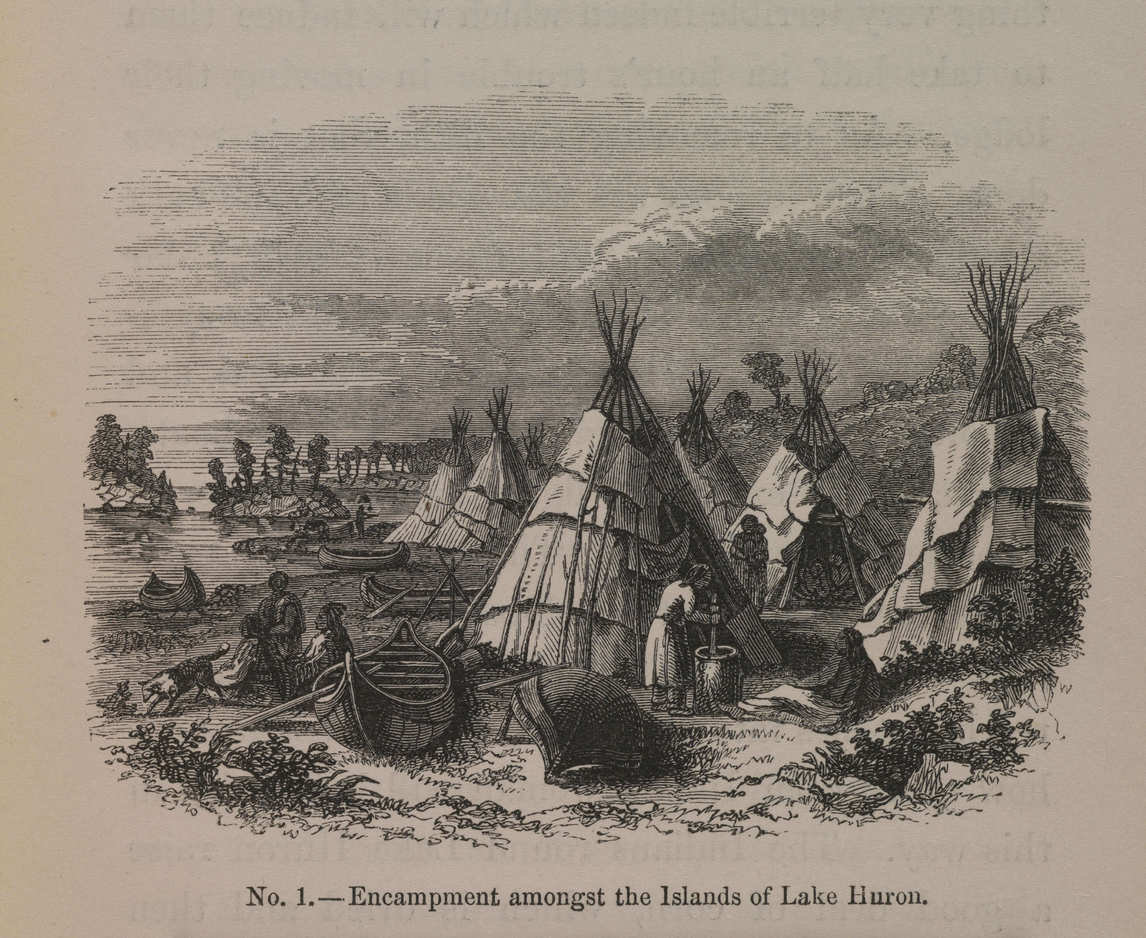

We know that Kane was under immense pressure to honour the contract for twelve paintings commissioned by Canada’s colonial government. It may be that the threat of a lawsuit for non-compliance compelled Kane to simply duplicate subjects under the pressure of time. But how do we explain triplicate versions of a single image, such as with Running Buffalo, c. 1849–56, Assiniboine Hunting Buffalo, c. 1851–56, and Assiniboine Running Buffalo, c. 1849–56? And how should we think about the duplicate renderings of works outside of the twelve? (For example, A Sketch on Lake Huron, 1849–52, and Indian Encampment on Lake Huron, c. 1845; or Flat Head Woman and Child, Caw-wacham, c. 1849–52, and Caw-wacham, Flat Head Mother and Child, c. 1848–53.)

In the book The First Brush: Paul Kane & Infrared Reflectography (2014), Royal Ontario Museum curator and anthropologist Ken Lister and ROM paintings conservator Heidi Sobol present their research on Kane’s paintings using current scientific methods. They are particularly interested in investigating instances of multiple versions to establish which painting is the original, and in analyzing Kane’s technique and execution to better understand the development of a painting’s content.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements