Paterson Ewen’s approach to painting was consistent throughout his career. On the surface, it appears merely eclectic, driven by interest and passion without any overarching structure or end goal. Ultimately, though, his explorations of new subject matter led him to experiment with styles and materials that transformed the specific subject he was focused on. Ewen’s ability to balance changing styles, themes, materials, and technique reflects how he internalized his artistic process and eventually embraced change as a constant in the world.

The Marriage of Gesture and Texture

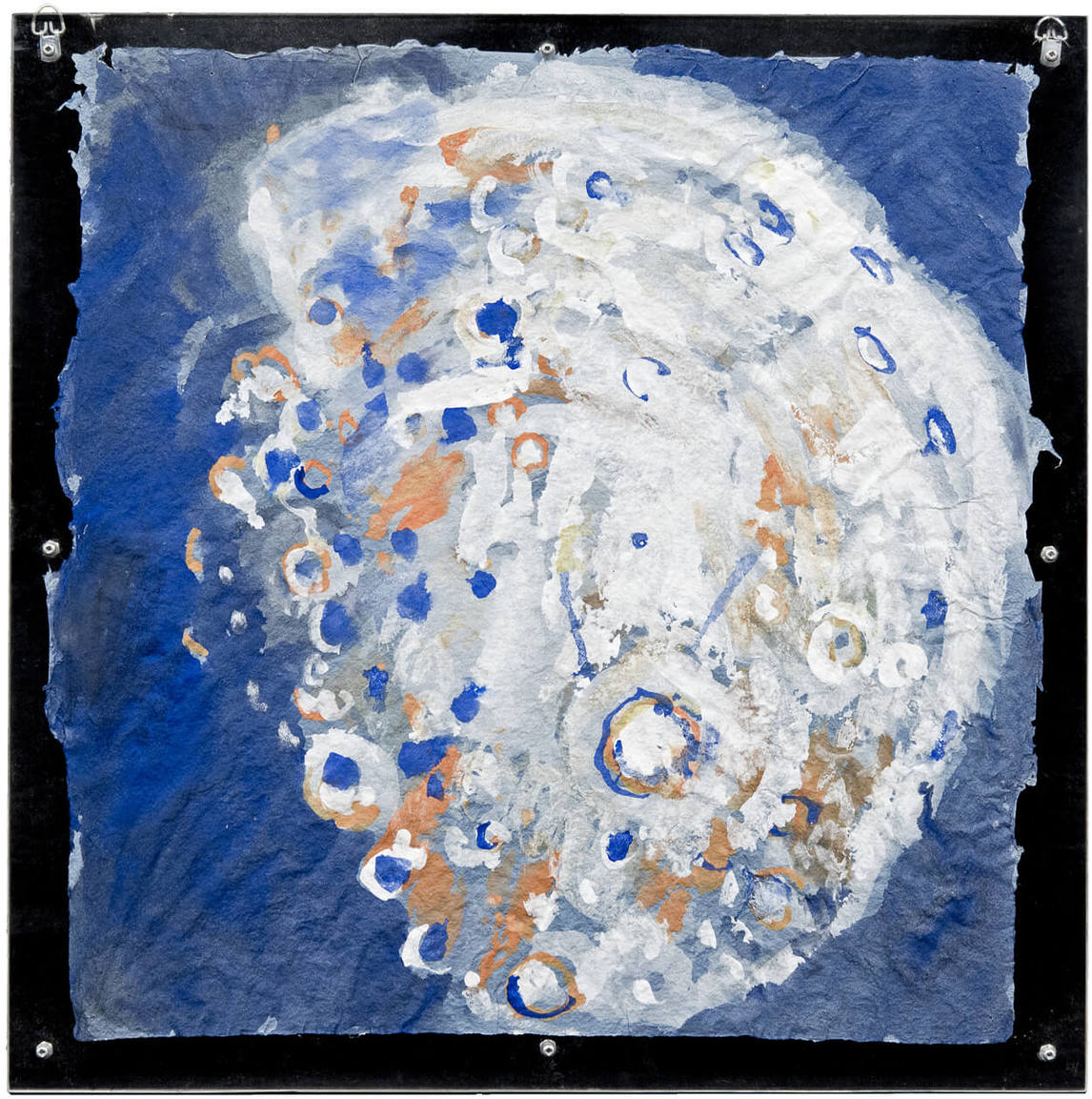

Common to all of Paterson Ewen’s works is his attraction to the physical process of making art. As an abstract painter in the 1950s, he embraced the expressive, exuberant brushstrokes typical of some of the Automatistes and Abstract Expressionists. In his untitled pastels on Fabriano paper in the early 1960s, Ewen was fascinated to see how “the texture of the paper showing through the pastel suggests that it’s happening now, that it is alive.” Of the mixed-media works he began in the 1970s, he said: “The work became a lot more fun when I was able to start nailing stuff on it.” And, of course, this physicality found its most potent expression in Ewen’s handmade-paper works, such as Moon, 1975, and especially in his signature gouged plywood works, such as Moon over Water, 1977.

Ewen’s gouging technique, which combined painting, sculpture, and even woodblock printing, defined a new kind of gestural painting in Canada and internationally. Ewen described his process:

I get an image in my head somehow or other, from someplace or other, and I live with that image for a while.… The image wants out, my hands and eyes are ready for the attack on the plywood, my intelligence exerts an automatic restraint, the adrenalin flows and the struggle begins.

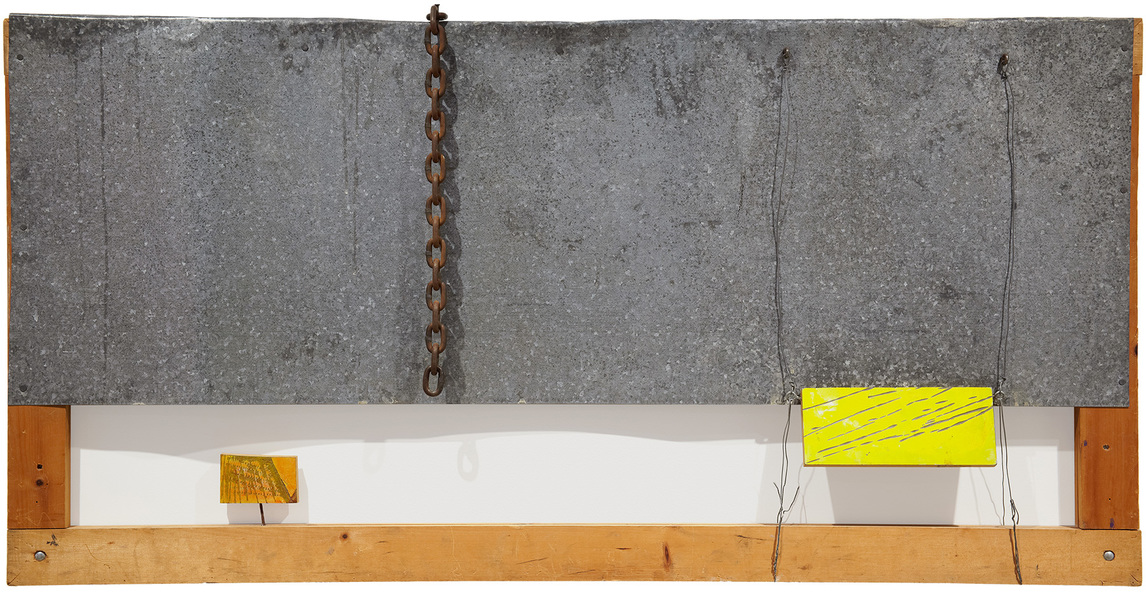

The physical beginning involves gathering materials and tools in advance of the struggle, wood, machine tools, hand tools, paint, and a myriad of things. A length of wire becomes rain, a piece of link fence becomes fog and so on, obviously a physical activity running parallel with the fermenting images in my head.

Once I place the plywood on the sawhorses and touch a magic marker to the surface to begin a vague drawing of the image, the activity begins to accelerate. Drawing is followed by routing and thoughts of colours, textures, materials rotate in my mind … things get nailed on, glued on, inlaid, or stamped on by a homemade stamp.…

Perhaps I can risk saying something that only the artist would know or dare to proclaim, and that is that once begun, the work cannot fail. This is so because I make it come out.

Ewen subsequently applied colour using rollers and brushes, depending on the surface and the area to be covered, roughly following the pastel drawing that preceded the routing. For the plywood works, he used acrylic paint, which adhered better than oil-based paint and had muted hues that better revealed the untreated wood underneath.

Paterson Ewen, Thunderchain, 1971, steel bolts, wire and chain, galvanized steel, engraved linoleum, and wood, 94 x 183 cm, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto.

Ewen’s richly textured, animated surfaces make tangible the forces of nature. In essence, nothing in his work is still. Ewen understood that change is the only constant, and rarely does he depict an idyllic landscape devoid of movement. Rain falls and is blown by the wind; ocean currents are driven by underlying forces, as shown in Ocean Currents, 1977. The rotation of stars around Polaris, the phases of the moon, the comets, sunrises and sunsets, solar eclipses, and even galactic cannibalism, as in Cosmic Cannibalism, 1994, all speak of motion in the universe. Whether it is the irregular patterns in the seemingly static Blackout, 1960, or the raw surface of the handmade paper in Coastline with Precipitation, 1975, or the deep gouges in plywood that recall those carved by insect larvae burrowing inside tree bark or those scoured by glaciers flowing over rock, Ewen reveals the mutability of the apparently immutable and makes us aware of unfamiliar forces within the familiar. His works appear to be undergoing transformation before our very eyes. As writer Shelley Lawson concludes, “The results are powerful work as rough-hewn and rugged as the Canadian landscape, as unmercifully omnipotent as the natural phenomena they represent and with a character as imposing yet sensitive as Ewen himself.”

Series and the Search for Meaning

Ewen appears to draw on Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890), whose landscapes attempted to visualize the creative energies of nature, and the first generation of German Expressionists, Die Brücke (The Bridge), whose landscapes were a tool for self-expression, as can be seen in Winter Moonlit Night, 1919, by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880–1938). Yet Ewen pushes these ideas a step further. Ewen internalizes the landscape entirely and makes it a register of the artist’s inner turmoil. As writer Adele Freedman notes, “Like his plywood panels, Ewen is scarred, but stubbornly he endures. His life seems to turn in cycles. Peaks and valleys. Highs and lows. Extremes.” In essence, “his work … deals in landscape as weather; landscape as psychological place and event.” It is perhaps unsurprising that Ewen created so many series, as he attempted to capture this mutability of the universe and with it the vagaries of his own life.

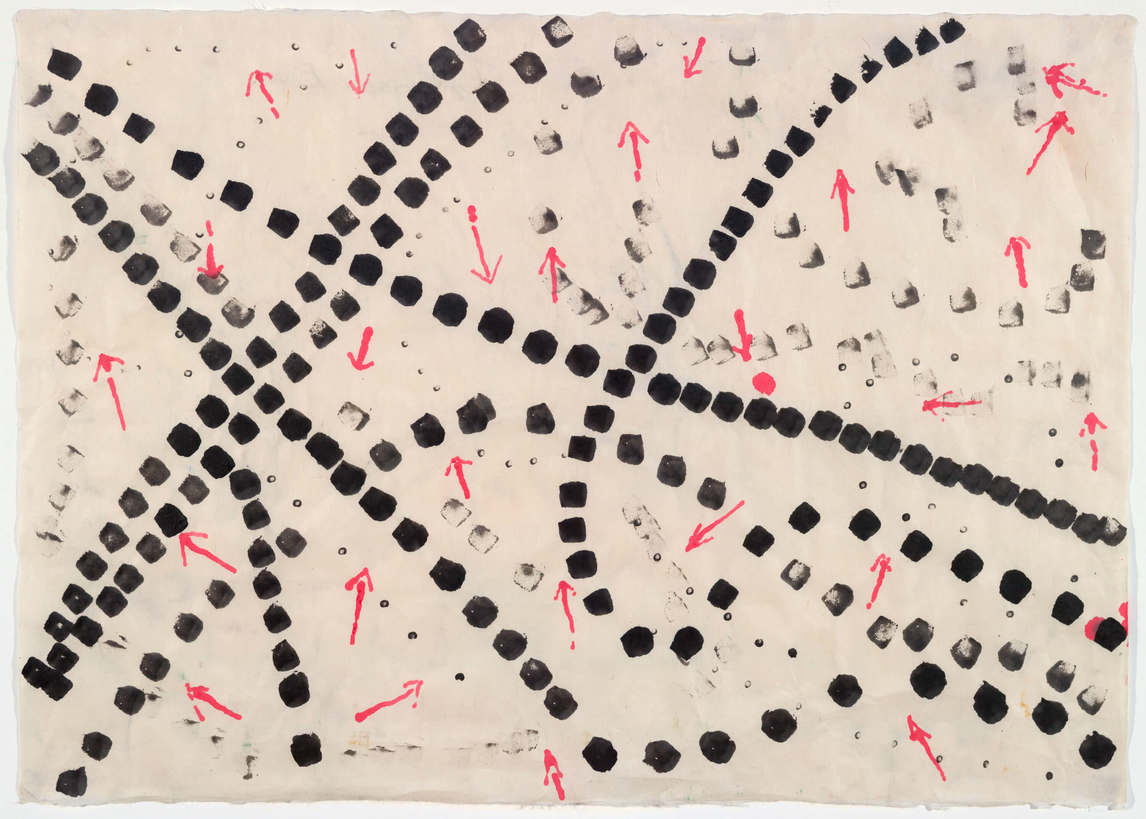

The idea of projecting human characteristics and beliefs onto the elements, whether terrestrial or celestial, goes back to the earliest recorded civilizations, but Ewen made that relationship intensely personal. The Lifestream series, for example, reveals Ewen’s discontent with the traditional conventions of painting but also reveals his own search for meaning. Many of his subsequent figurative landscapes are turbulent: they involve thunderstorms, hail, and rain, as in Thunder Cloud as Generator #2, 1971, and reflect something of the artist’s volatile life. At the same time, the arrows and other symbols of scientific diagrams early on show an attempt to keep the chaos under control and prevent viewers from delving too deeply into the autobiographical elements of the work. Perhaps the most important, however, is the Moon series.

Ewen explored moons in every phase, and returned to them again and again in every period of his life and in every medium in which he worked. Compare, for example, Moon over Water, 1977, a partially obscured full moon flanked by lingering black clouds that suggests Ewen’s ongoing anxiety, with Moon over Tobermory, 1981, a half moon surrounded by the archangel Gabriel possibly sheltering the artist and helping him overcome fear. And contrast these two with Many Moons II, 1994, highly colourful sculpted variations on a full moon that appear to be celebratory. By tying the moon’s many faces to constant change in the natural world, Ewen made sense of his own moods and affirmed his connection to the universe.

Of Lines, Daubs, and Dashes

Lines, whether solid or broken, run like a thread throughout Ewen’s oeuvre. In his early works, it is line as contour that predominates: it encloses colour, controls it, provides structure. Like Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890), he applies his colour in lines, whether straight or swirling, as opposed to dots like the Pointillists. Colour threatens to fall apart when it is left too much to its own devices, as in Interior, Fort Street, Montreal [#1], 1951. In Ewen’s most successful abstractions, line directs and encloses his forms. They are less successful when line runs amok, in works such as Untitled, 1955. The lack of a clearly defined linear pattern or rhythm in this painting shows just how important structure is to Ewen’s art generally. Its importance and success is revealed in works like La Pointe Sensible, 1957.

In the Lifestream works, line in both its straight and dotted forms represents the flow of life: blood flowing through one’s veins, water flowing across the land, electricity snaking across the sky. In his Untitled, 1960, and Linear Figure on Patterned Ground, c. 1965, Ewen briefly experiments with the vertical line made famous by the Abstract Expressionist Barnett Newman (1905–1970), who used it to express the link between the earthly and the heavenly. However, Ewen soon returns to the horizontal line, using it to divide earth and sky or, more often, water and sky.

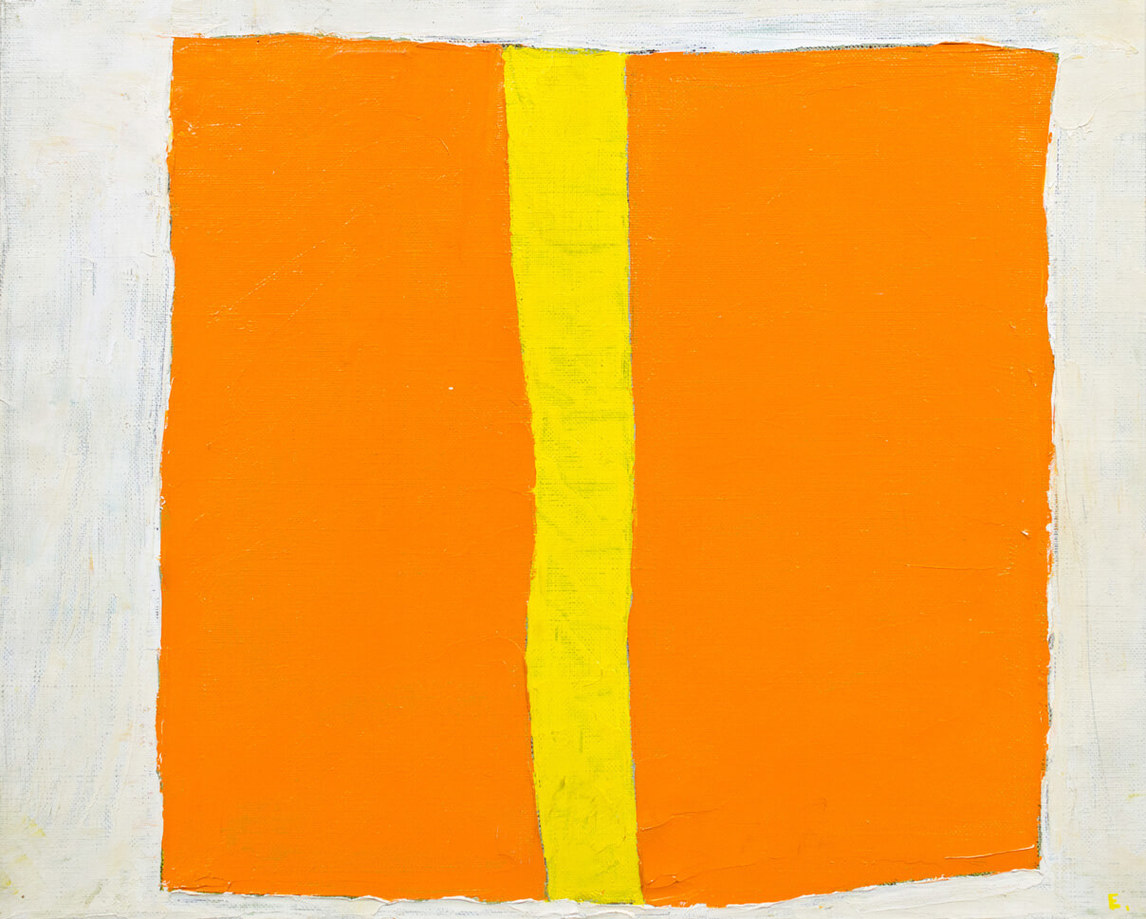

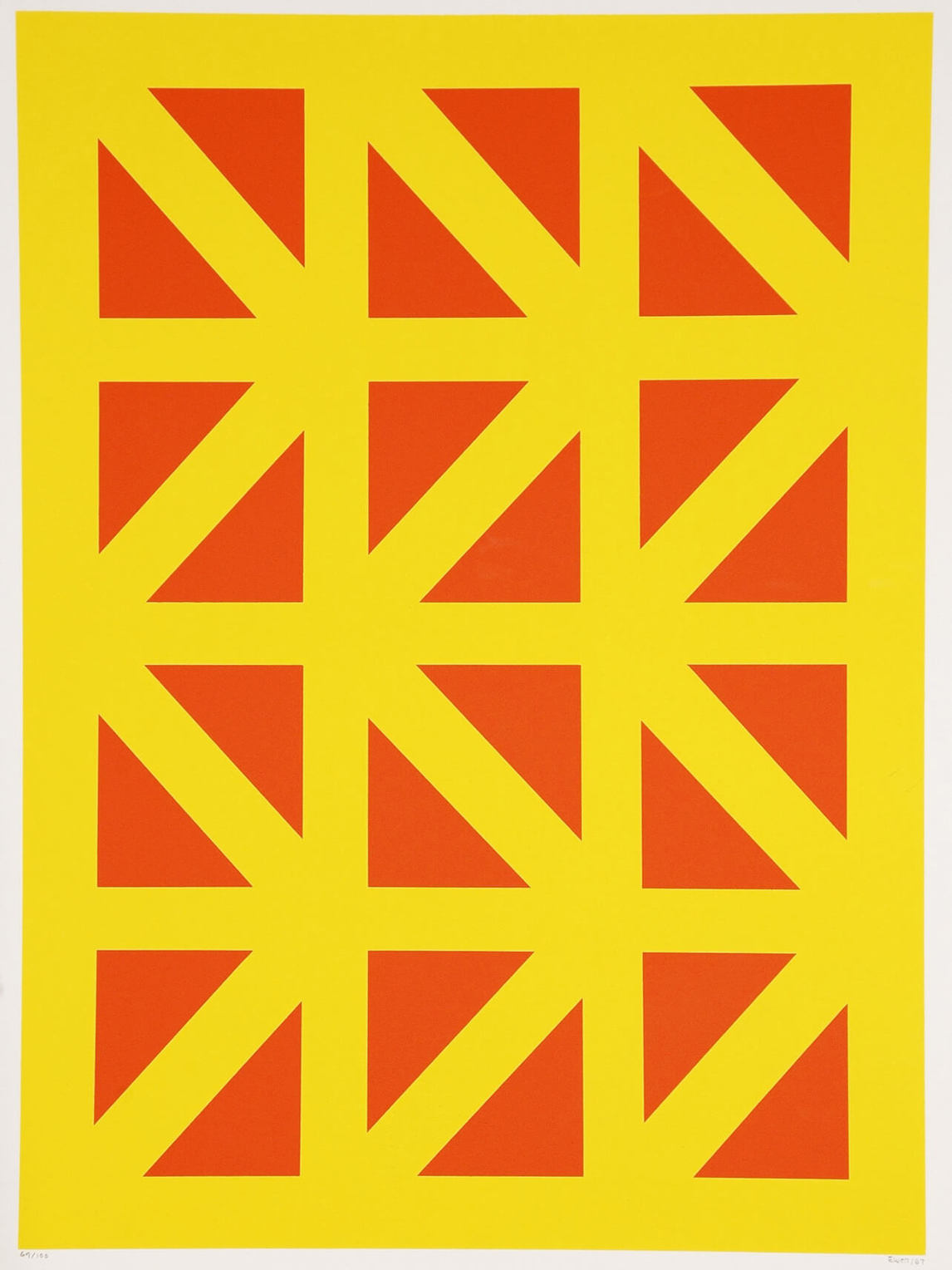

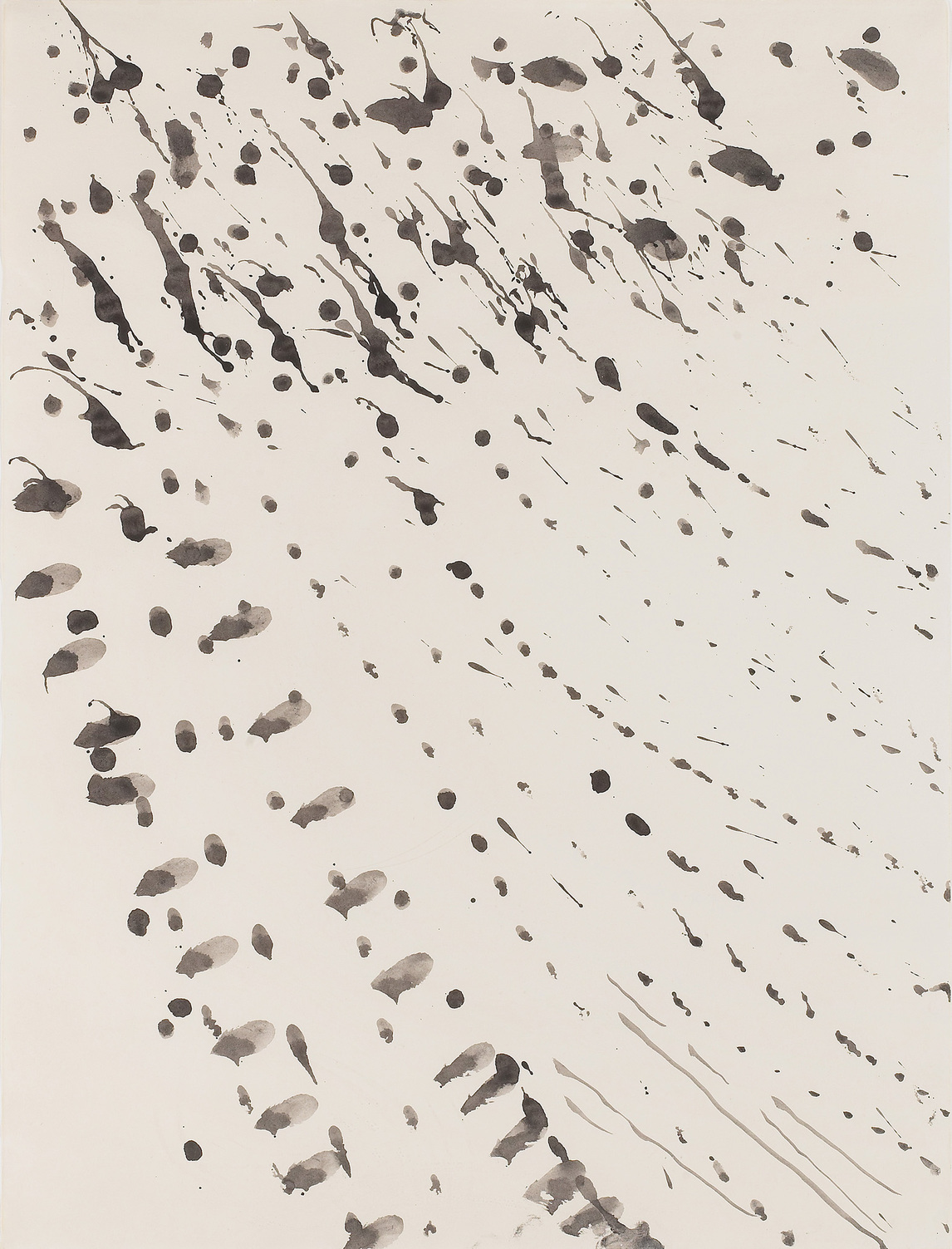

It is very likely that for Ewen, consciously or unconsciously, line was a metaphor for the stability and structure he sought in his own life and that his ability to master line meant he could master himself. When Ewen’s life was falling apart, he more fiercely attempted to rein it in. For example, when Ewen’s marriage to Françoise Sullivan (b. 1923) was disintegrating in the mid-1960s, he adopted the hard-edge style of the Plasticiens in such clean, straight-edged works as Untitled, 1967; Zig Zag, 1968; and Diagram of a Multiple Personality #7, 1966. By the 1970s, he had once again found his footing and the daubed lines are looser and more exuberant—for example, in Rain Hit by Wind #1, 1971, or The Great Wave, 1974.

Throughout Ewen’s works, we see this fluctuation between lines that are measured, subdued, and lines that are erratic, almost out of control. The effect is a range of moods: from the illusion of vast, ordered space created by the rigid lines in Galaxy NGC-253, 1973, to the celebratory, cosmic dance of the dynamic dashes in Star Traces around Polaris, 1973, and the chaotic exuberance of the every-which-way gouges in Decadent Crescent Moon, 1990. As Satan’s Pit, 1991, demonstrates, without colour Ewen’s work could survive, but without line it falls apart.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements