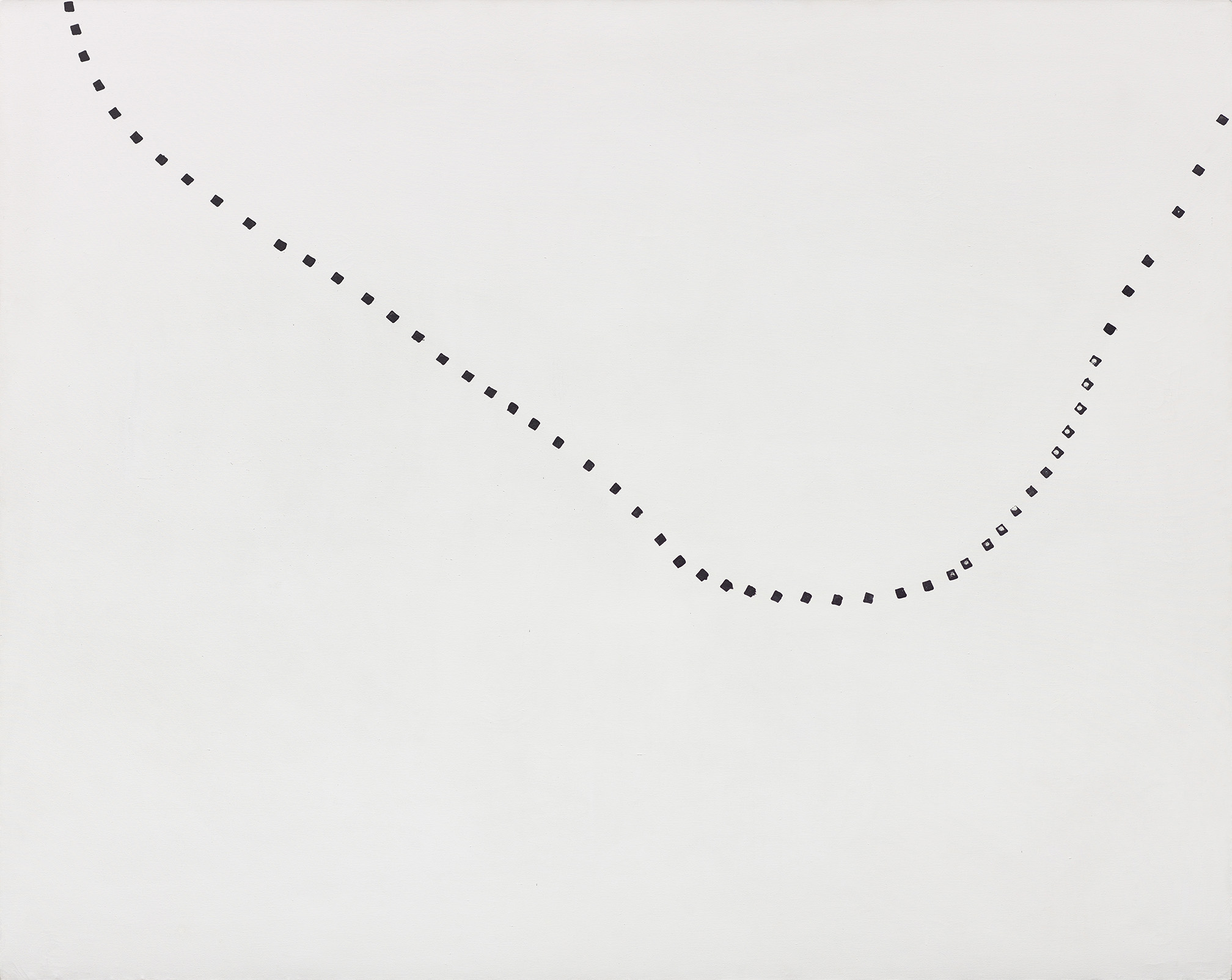

Traces through Space 1970

Paterson Ewen, Traces through Space, 1970

Acrylic on canvas, 172.7 x 213.4 cm

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Traces through Space, curiously enough, marks Paterson Ewen’s return to figurative painting. The work itself is abstract, involving an irregular curved, dotted line cutting across a white surface. It is much larger in scale than many of Ewen’s previous works and its human scale has a greater physical impact on the viewer. Ewen’s goal was to convey “the idea of a life stream that goes through everyone’s life and universal life.” He had recently undergone electroshock therapy, and here he may be signalling his own life force in an allusion to electronic waves.

Between 1958 and 1971, Ewen produced over two dozen paintings in his Lifestream series. In this, his second to last of the series, he explains: “I thought I was making an anti-art gesture in the formal sense with those last paintings. Daubing rows of dots on plain canvas with felt. But then somehow this turned out feeling like traces of things moving through space and this is what first suggested the idea of phenomena …” Thus began Ewen’s ongoing exploration of the weather and the cosmos, in works he called “phenomascapes.”

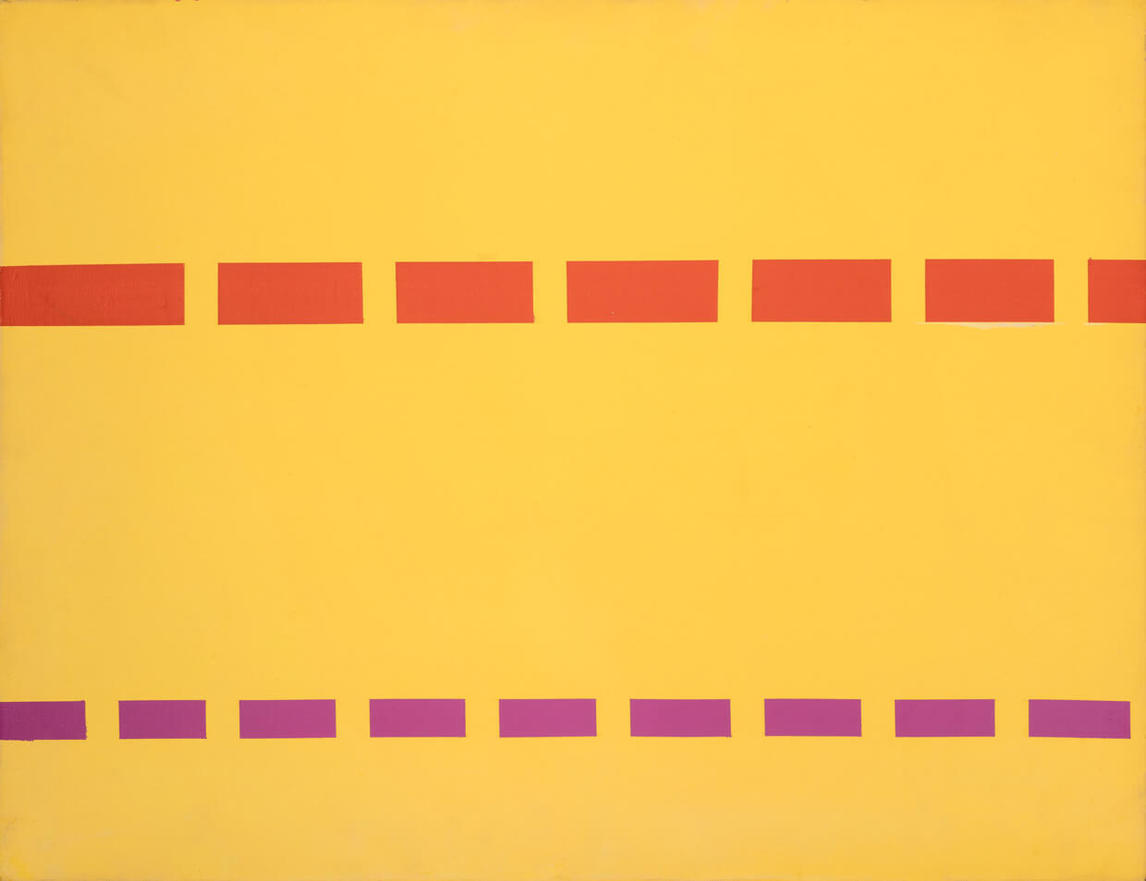

By the time he created Traces through Space, Ewen felt he had exhausted what he could do with abstraction. He had moved from complex and involved brushwork in his early pieces to the simplified lines and colour fields of his latest works. For example, Lifestream, 1959, sees Ewen shift from the Automatistes toward the more orderly nonfigurative works of the Plasticiens. By 1967, Untitled reveals a geometric abstraction with almost hard edges in the style of Claude Tousignant (b. 1932) and Guido Molinari (1933–2004). Untitled #3, 1969, created after Ewen relocated to London, Ontario, shows a further transition to the more minimal styles of David and Royden Rabinowitch (both b. 1943).

Key to all of the works in the series is the suggestion of movement across the canvas. Their emphasis on horizontality highlights the fact that Ewen never abandoned landscape painting entirely. Speaking of the Lifestream series in 1959, Ewen acknowledged that it “is a landscape, but it is stylized to the point of being almost symbolic. When you put it all together it flows. It’s about life in the most basic sense—mountains, rivers, boulders.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements