Paterson Ewen was unmistakably original. His work bridged figurative and abstract approaches, fused painting and sculpture to create a whole new medium, and broadened the definition of Canadian landscape, revitalizing national interest in this type of art. His legacy rests with how he successfully combined elements from the many influences he absorbed throughout his career, and from them created something unique. Moreover, his interest in the science of weather, celestial objects, and planetary vistas revealed an “earth” awareness that embraces key concerns of the day, such as our place in the universe at the beginning of the space age and the health of our planet.

Standing on the Shoulders of Giants

Paterson Ewen was called “the prospector” by his colleagues when he lived in Montreal, where he was working at the crossroads of a conventional figurative painting tradition and an emerging movement focused on abstraction. The nickname seems to portray the artist as someone who simply takes from each encounter without coming up with anything original. In Ewen’s case, this assessment is far from accurate. Because Ewen was largely self-taught, he inevitably turned to other artists for his lessons on art. However, he did not merely copy; rather, he always put his own stamp on his appropriations.

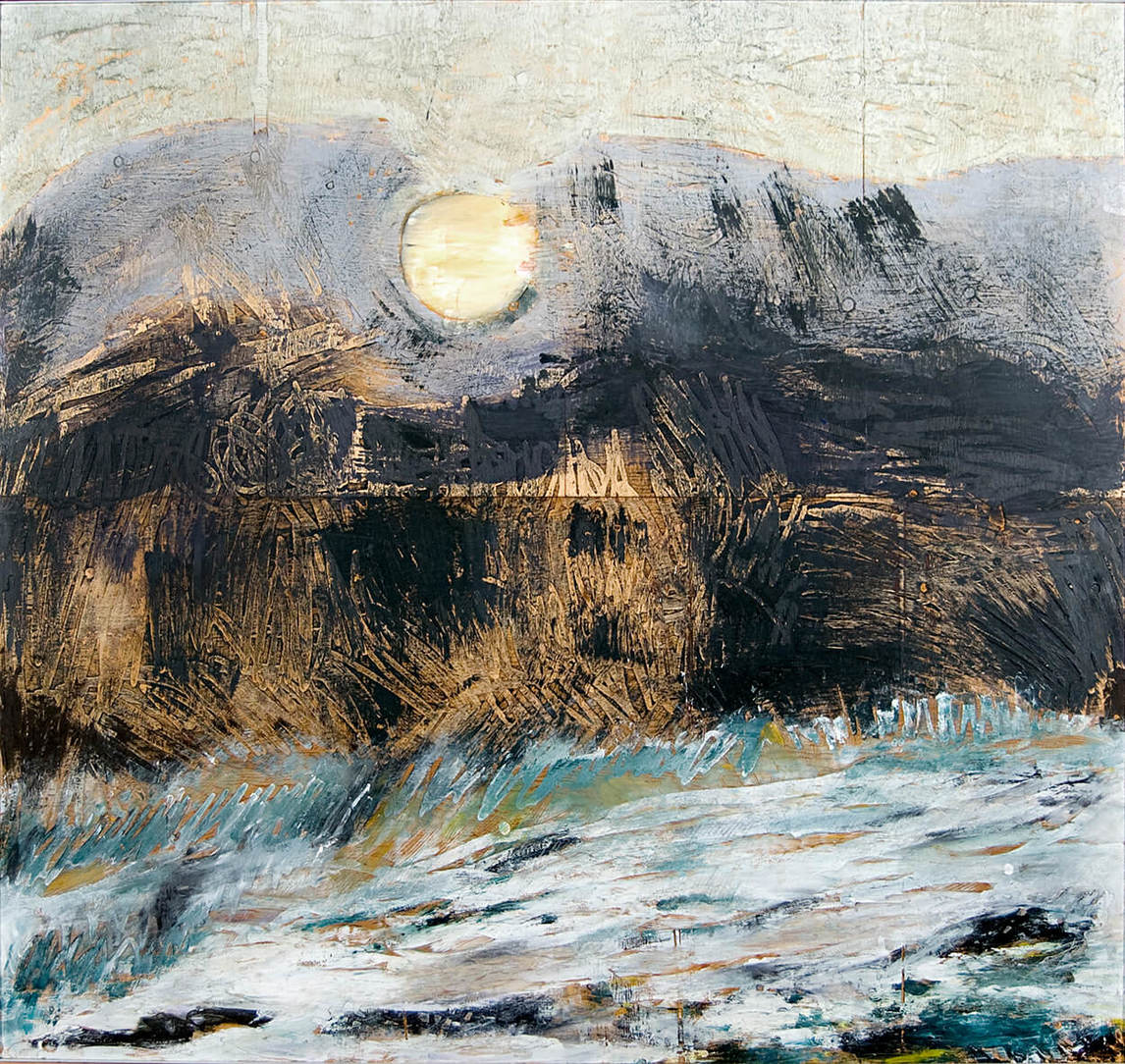

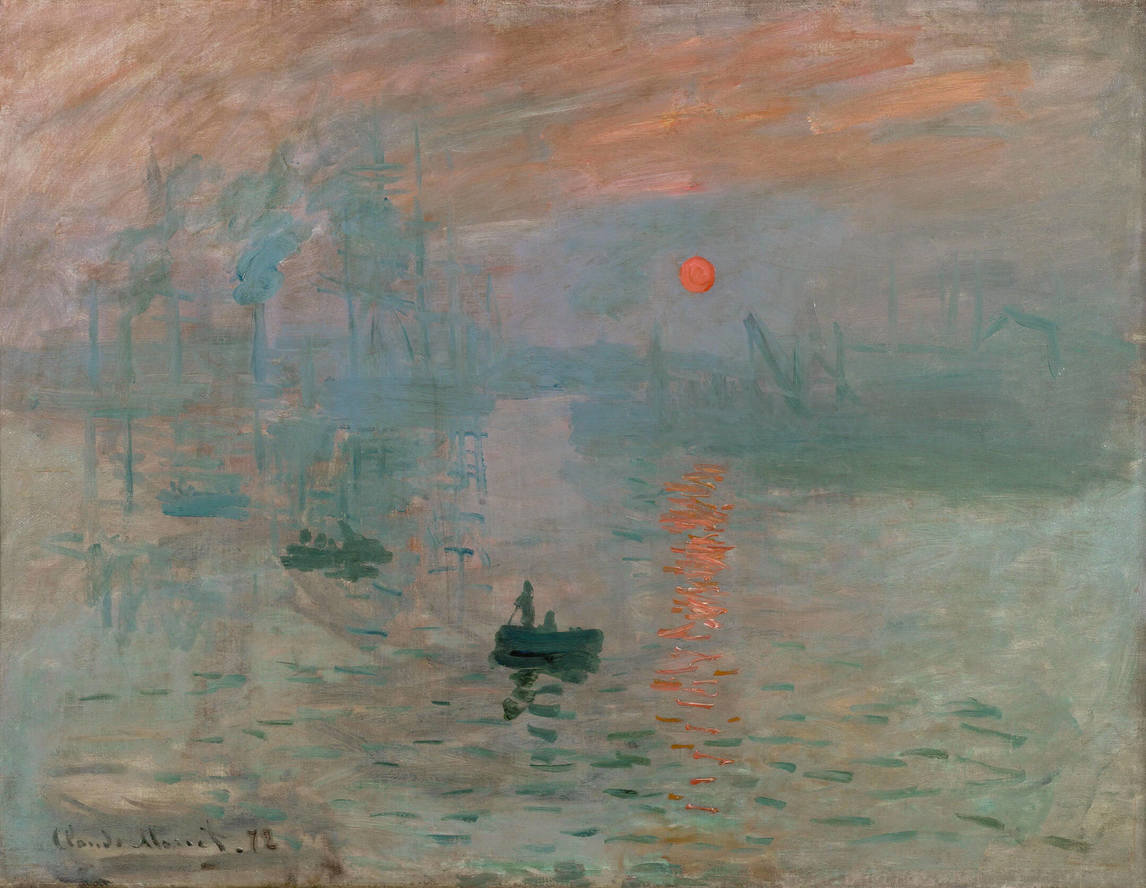

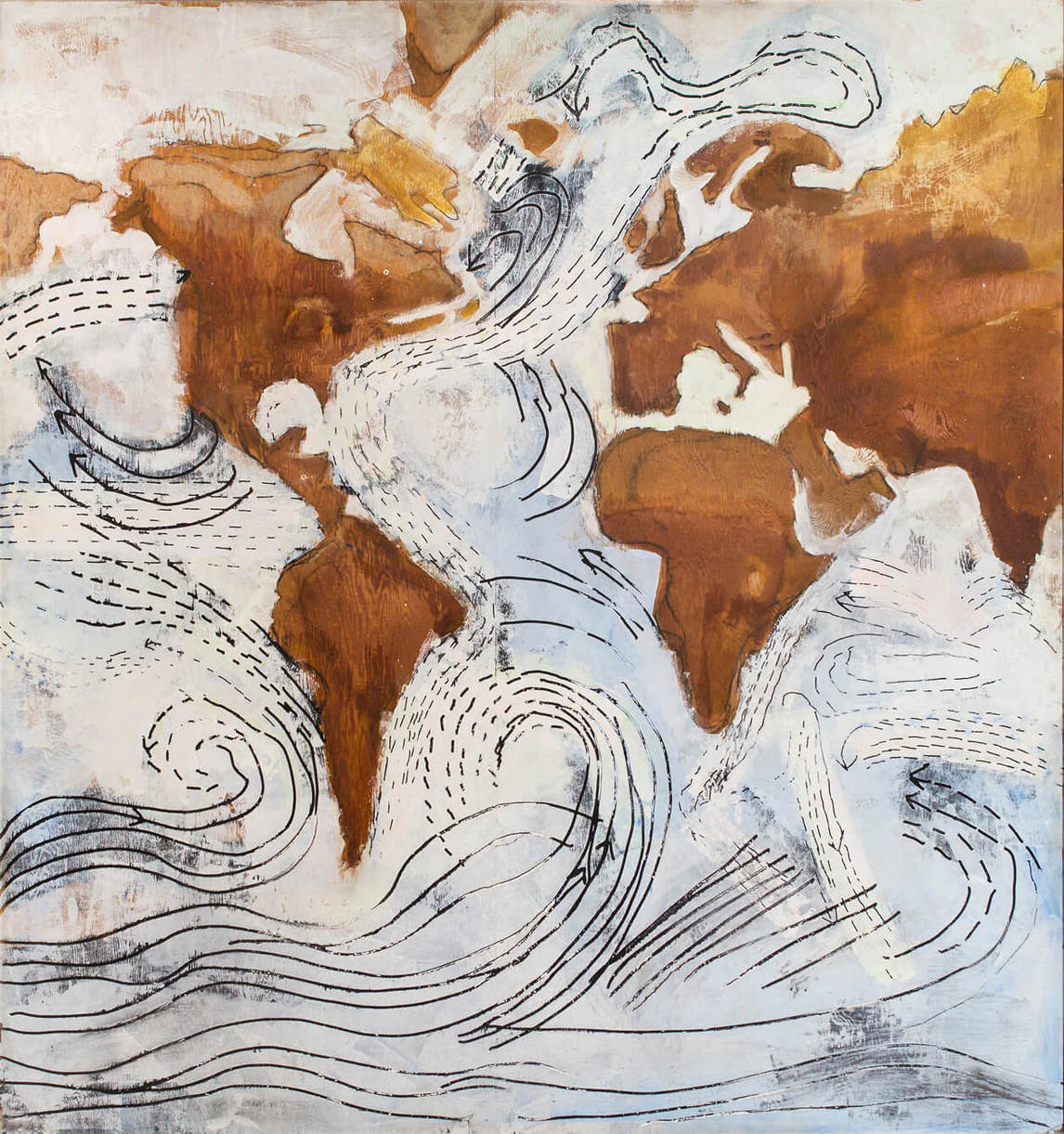

Like others before him, including one of his strongest influences, Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890), Ewen approached art as an ongoing dialogue with various trends both past and present. He was influenced first by Goodridge Roberts (1904–1974) and the Post-Impressionists, then by the Automatistes and the later work of Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960), the Abstract Expressionists, the Russian Constructivists, Claude Tousignant (b. 1932) and the Plasticiens, nineteenth-century Japanese woodcut artists, and so on. He never denied any of these; in fact, he embraced them. Ewen’s landscapes, for instance, beginning with Typhoon, 1979, often reference J.M.W. Turner (1775–1851) and John Constable (1776–1837) in terms of subject matter and treatment. Ewen stated:

I don’t mind being compared to [Claude] Monet at all. I don’t see how someone this decade could do landscapes that involved weather and atmosphere and not be connected to the Impressionists … They said of Constable that he painted the weather. And he has been a very direct influence. When he was painting his clouds over fields, he was, along with the scientists of the time, studying cloud formations. It is interesting that Turner (another one of my great heroes) painted the atmosphere and was a direct influence on the Impressionists. If I am influenced by the Impressionists to some degree, it’s quite true.

When Ewen borrows a subject directly, as with Ship Wreck, 1987, which is derived from Moonlight Marine, 1870–90, by Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847–1917), there is no confusing one work with the other. Similarly, Ewen combines Japanese woodcuts and van Gogh’s impasto brushwork, yet the resulting gouged plywood works are unique. His depiction of Halley’s Comet in Halley’s Comet as Seen by Giotto,1979, for example, one of Ewen’s most reproduced works, is taken from the Adoration of the Magi, 1304–06, by Giotto (1266/67–1337). Ewen has borrowed Giotto’s rendering and rich palette, but the plywood gouging and Ewen’s vibrant brushwork make this painting all his own. What many of Ewen’s contemporaries admired about him was exactly this: his constant mining of art, both contemporary and historical, and his ability to draw from it a new lesson, a new phrasing that is folded almost seamlessly into his current work. For Ewen, the history of art was a source of inspiration that he returned to over and over again.

Revitalizing the Landscape

Paterson Ewen’s return to figurative work in the early 1970s was part of a growing rejection of abstraction in favour of more representational work. In turn, it brought about a rejuvenation of painting at a time when the Minimalist sculptor Donald Judd (1928–1994) boldly declared, “It seems painting is finished.” Among the leaders of this new trend, which generated such movements as Neo-Expressionism, was Philip Guston (1913–1980), formerly an Abstract Expressionist, who exhibited new, figurative works at the Marlborough Gallery in New York in 1970. The show drew the attention of many artists and scathing reviews from critics. Ewen mentions having seen an issue of Art in America or another art magazine showing Guston’s work.

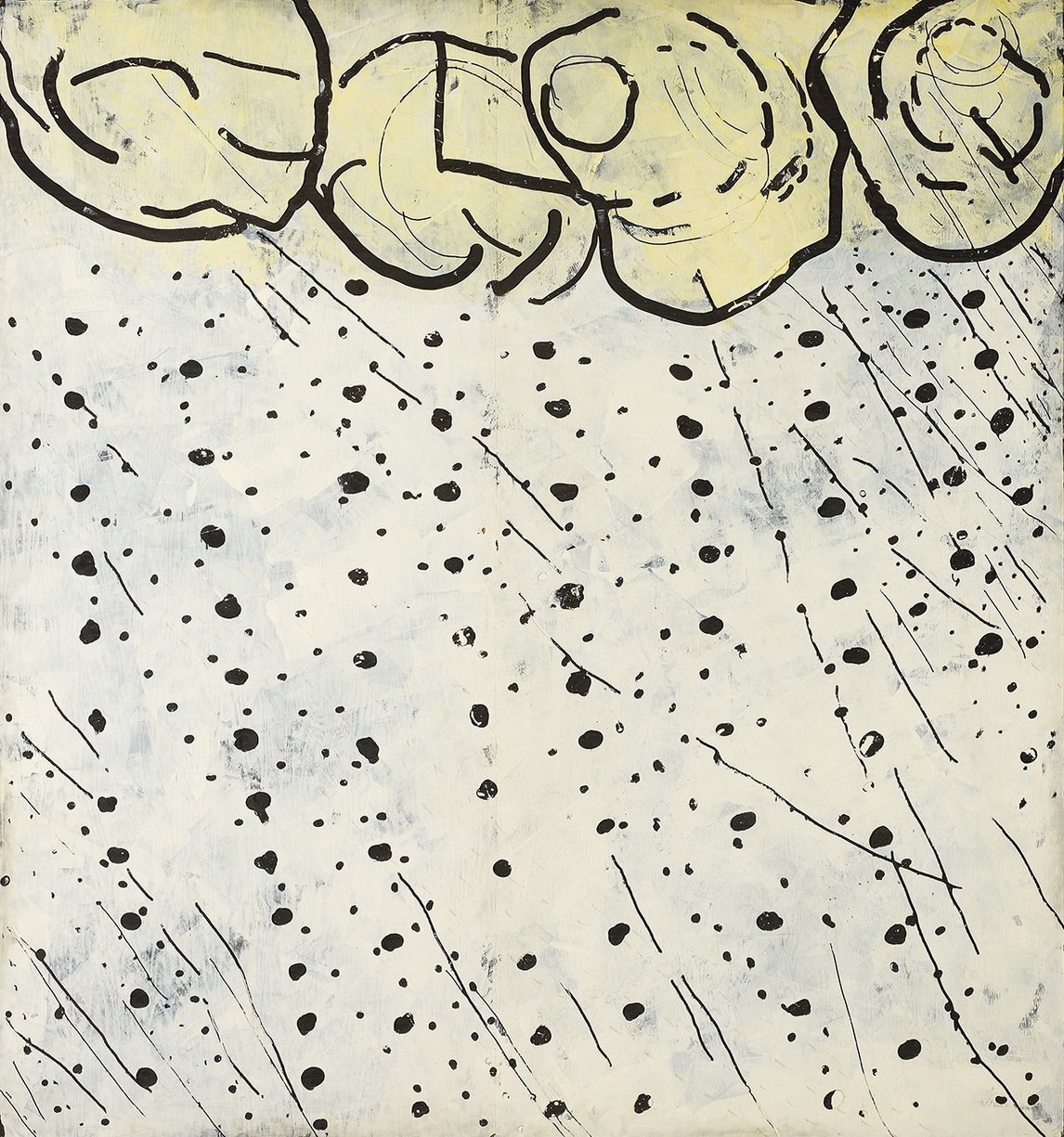

In Canada, contemporaries such as Jack Shadbolt (1909–1998), Joyce Wieland (1930–1998), Jack Chambers (1931–1978), and David T. Alexander (b. 1947) were trying to redefine the concept of the landscape. Ewen’s understanding of landscape was broader: in both his abstract and figurative works he conveyed land, water, and space. As art historian Roald Nasgaard noted about Ewen, “What always made him unique was his capacity, in a period when ‘real’ painting was abstract painting, to find a strategy to make landscape painting vital again.” It is doubtful that Ewen thought much about the implications of what he was doing. He tended to simply get an idea in his mind and forge ahead. However, Ewen’s return to figurative painting combined with his interest in representing weather and the cycles of nature in his first “phenomascapes”—for example, Precipitation, 1973—drew critical attention precisely because they were not a mere revival of the landscape painting the Group of Seven had done before him. They established a very different way of looking at nature.

As the American painter Eric Fischl (b. 1948) states, “In many ways Paterson Ewen’s paintings were a natural expression of what is, I think, a profound Canadian experience: namely, nature and the painting of the landscape. Here was someone who, in the 1970s, found a way of reinvigorating that tradition in an authentic way by recalling the power of nature.” His 1974 painting Full Circle Flag Effect shows the complete cycle of rain falling and bouncing back up. When tiny water droplets bounce off the surface of a body of water, they sit in a line for a microsecond. If the wind hits those droplets when they’re perfectly aligned, the lines become wavy, which is known as the flag effect. Ewen’s landscapes were big physical expressions of the force of the elements and the planets. “The sheer physical scale and power of the works,” contended curator Matthew Teitelbaum, “revitalized interest in painting and in landscape as a subject matter.”

In highlighting the processes of nature, its life stream, as Ewen called it, he not only broadened the definition of Canadian landscape painting but presaged an awareness of the earth and the ecocritical art of such later artists as Aviva Rahmani (b. 1945) and Mark Dion (b. 1961).

Prospecting Science

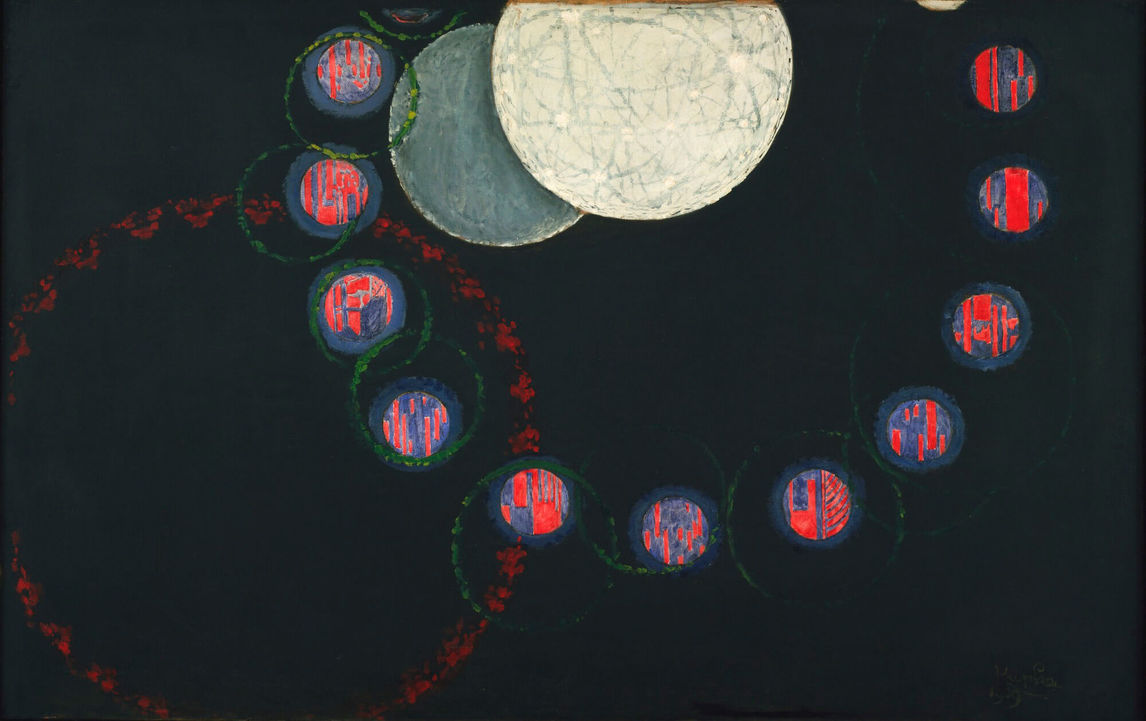

Paterson Ewen’s fascination with and use of science in his art heralded a new wave of artistic interest in astronomy in Canada and globally. Artists throughout history have occasionally delved into the sciences for technical and thematic inspiration, most notably Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) and more recently Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968). Ewen himself was influenced in this regard by John Constable (1776–1837) and František Kupka (1871–1957). Although Ewen spent “nights of searching, with a telescope, for the planets, moons, and stars with my sons,” he was not looking to science as inspiration for his work. Instead, it found him.

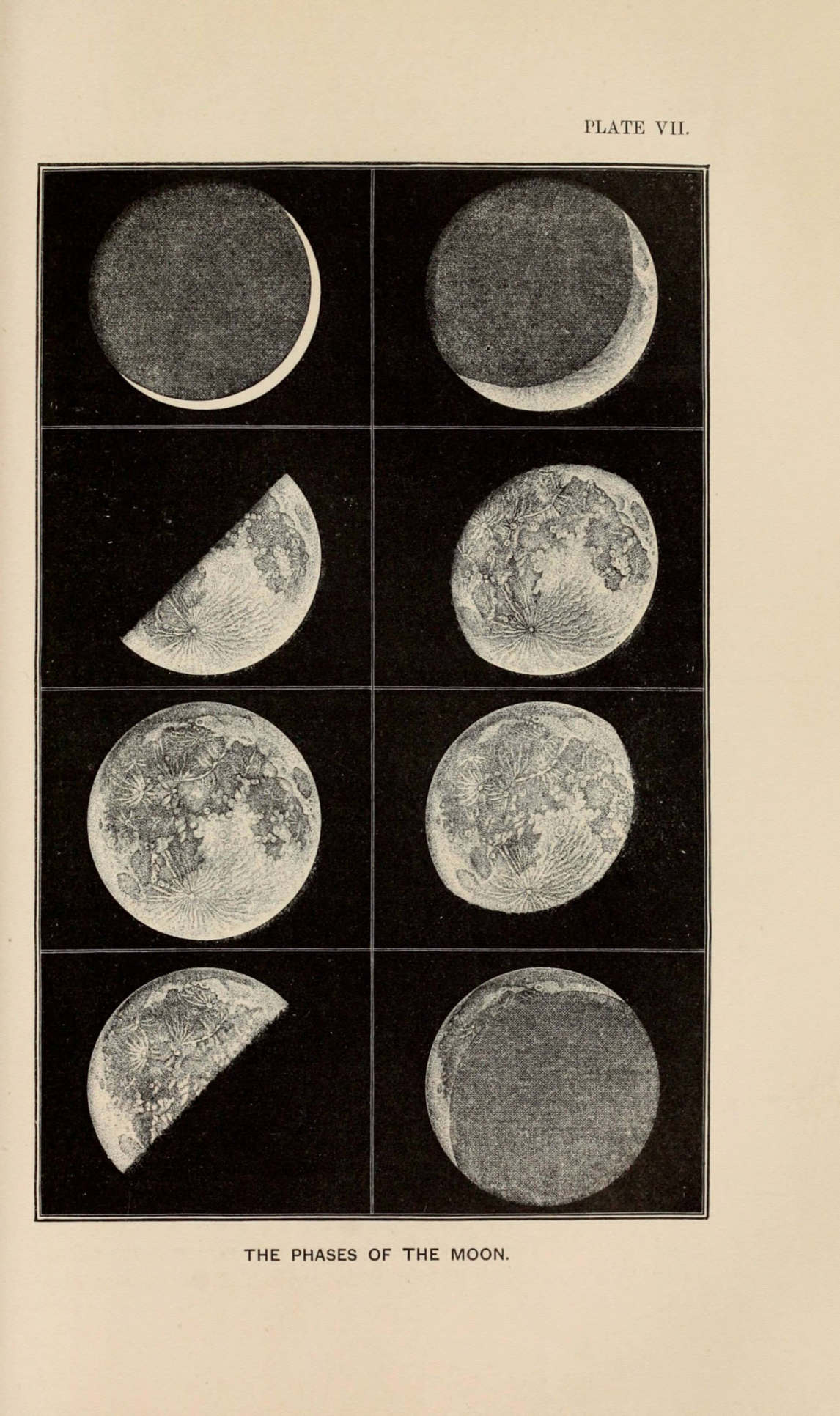

Throughout the 1960s, the “space race” between the United States and the U.S.S.R. was front-page news. But Ewen’s first celestial works, such as Blackout, 1960, occurred unintentionally. By the time he created his earliest gouged plywood works, specifically Solar Eclipse and Eruptive Prominence, both 1971, men had walked on the moon and telescopes were probing deeper and deeper space or examining closer celestial objects in greater detail. Yet, these were still highly unusual themes for artists, and source material was hard to come by. He turned his attention to the physical sciences, drawing initially upon the beautiful black and white photos in such old texts as Clarence Chant’s Our Wonderful Universe: An Easy Introduction to the Study of the Heaven (1928) and Robert and Woodville Walker’s The Origin and History of the Earth (1954) and the prints in Amédée Guillemin’s The Heavens (1871).

Ewen was at the vanguard of a diverse group of artists who have subsequently depicted celestial subjects in their work, including his student Thelma Rosner (b. 1941); Rafael Lozano-Hemmer (b. 1967), Adam David Brown (b. 1960), and Dan Hudson (b. 1959) in Canada; as well as Katie Paterson (b. 1981), Josiah McElheny (b. 1966), Björn Dahlem (b. 1974), and Zhan Wang (b. 1962) abroad. His paintings of planets, comets, galaxies, and other celestial features have encouraged others to explore beyond our immediate surroundings.

Teaching beyond Tradition

Paterson Ewen taught for nineteen years in London, Ontario, first at H.B. Beal Secondary School and then in the fledgling Department of Visual Arts at the University of Western Ontario. As Kim Moodie (b. 1951), who was first a student of Ewen’s and later his colleague at Western, recalled, “Ewen set a powerful example to students by his total commitment to art. He believed in the power of art as a personal statement and focused everything—his character, life-style, energy and spirit—to making art.” Ewen was very well versed in Canadian and international art trends, both contemporary and historical, and he stressed the need to be aware of art’s history. In turn, his intuitive understanding of aesthetics and the elements of composition, colour, and form, was exceptional.

With his gouged plywood works, such as Solar Eclipse, 1971, Ewen was breaking with tradition just as formalism was reaching its peak in America by the early 1970s. Art critic Clement Greenberg (1909–1994) and his followers, such as Michael Fried (b. 1939), were advocating for the integrity of each medium; for example, that painting should be restricted to two dimensions as its surfaces are inherently flat. In contrast, Ewen never imposed a style, philosophy, or theory on his students, and his assignments provided lots of room to explore. His main contribution to Canadian art was not, in this sense, a particular style or technique but encouraging his students—and other young artists—to experiment and to push the boundaries of art.

As a mentor, a teacher, and an artist, Ewen influenced Eric Walker (b. 1957), Peter Doig (b. 1959), Sarah Cale (b. 1977), and Yechel Gagnon (b. 1973), to name but a few, but his impact goes beyond painting. In the Vapor Trails concert tour book, drummer and lyricist Neil Peart of the Canadian rock band Rush acknowledges that a series of works by Ewen helped to inspire the 2002 song “Earthshine.” Poet rob mclennan wrote a tribute called “on the death of paterson ewen.” It is Matthew Teitelbaum, though, who perhaps best summed up Ewen’s achievement: “He was a leader, an innovator, a discoverer of new languages of art.… He gave us permission to dream and imagine.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements