Paterson Ewen (1925–2002) was fascinated by science and the landscape. After serving in the Second World War he found solace for depression in making art. He enrolled at the Montreal Museum School of Fine Art and Design, where he was influenced by Goodridge Roberts. Soon he also discovered the Automatistes. Yet Ewen’s early success as an artist was tempered by a failing marriage and his subsequent struggle with depression and anxiety. A move to London, Ontario, in 1968 gave him new energy, and there Ewen developed a unique approach to painting the landscape that became his hallmark. He died in 2002, leaving an indelible mark on Canadian art history.

The Early Years

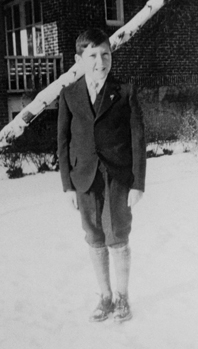

Paterson Ewen was born in Montreal on April 7, 1925. His father, William (Bill) Ewen, was born in Aberdeen, Scotland, in 1888, and raised in a tough working-class district. At seventeen, Bill was recruited by the Hudson’s Bay Company and came to Canada to work as a fur trader. Paterson’s mother, Edna Griffis, was born in St. Catharines, Ontario, in 1886. The couple met in northeastern Manitoba and married in July 1917, living briefly in Bersimis (today Pessamit) on the north shore of the St. Lawrence River and in Winnipeg before settling in Montreal, where Bill took a position with Canadian Fur Auction Sales. Paterson’s only sibling, Marjorie, was born in 1920.

It is difficult to pinpoint when the young Paterson’s affinity for art first emerged. As a toddler, he apparently asked his mother for wax, which she provided and he used to make small figures and a tree. The Ewen household was nearly devoid of artistic ornament. As his maternal cousin noted, Paterson’s mother “was a perfectionist housekeeper, and she used to say she never wanted to own anything that she’d be upset if it broke.… There was certainly nothing to inspire an artist.” To her credit, though, Edna did purchase reproductions of The Blue Boy, 1770, by Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788); The Gleaners, 1857, by Jean-François Millet (1814–1875); and Boy with a Rabbit, date unknown, by Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1725–1805), after her son complained at age thirteen about how little art there was in the house. (In interviews Ewen identified the works his mother purchased; however, there is no known painting by Greuze titled Boy with a Rabbit. It likely was Boy and Rabbit, c. 1814, by Henry Raeburn (1756–1823), which like The Blue Boy was popular and widely reproduced at the time.) At sixteen, Paterson learned that his paternal grandfather had been an amateur sculptor of some repute in Aberdeen. At that point, he attempted a clay bust of his sister, Marjorie—his first substantive artistic endeavour.

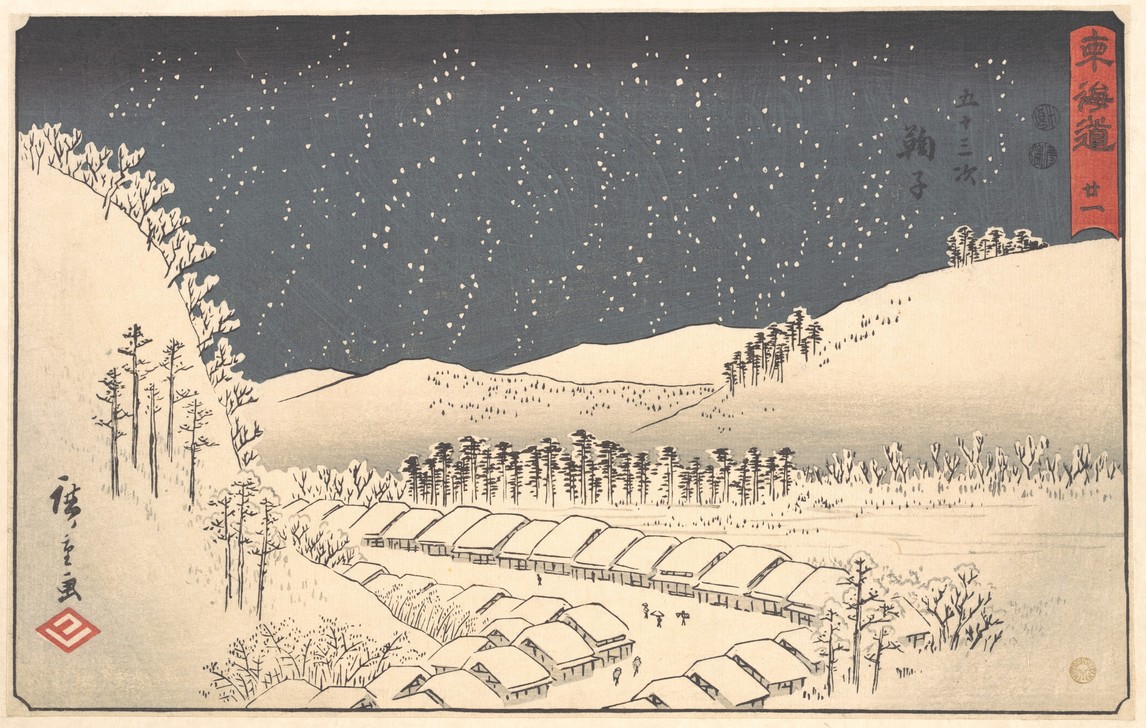

Probably the most influential experience of art in Paterson’s childhood was his visits to his maternal aunt Emma’s home in Ottawa, where he frequently went to the National Museum of Man (today the Canadian Museum of History) to study rock samples, dinosaur bones, and Group of Seven landscapes. His aunt’s family was friendly with a Japanese diplomat who gave Paterson a book of Japanese woodblock prints by Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) that he treasured. Years later, landscape, science, and Japanese art would all figure technically and thematically in Ewen’s artwork.

Paterson subsequently related, “I came to art on my own. I had only periodic classes in grade school—you know, how to make rainbows—and even my high-school classes never got much beyond caricature. None of my friends had any connection with art. Other than Grandfather, I had no role models as an artist. I liked drawing and trying to make something out of wood or plasticine, but I was always discouraged that my cows never looked like cows. I thought you needed a special gift from heaven to be an artist, and I didn’t have it.”

Military Life and Art Education

Paterson Ewen in his army uniform, c. 1944, photographer unknown.

The Second World War broke out when Ewen was fourteen, and four years later he convinced the doctor doing his physical exam to record his eyesight as “perfect” rather than “shortsighted,” so he would not be rejected for service. He worried that the war would end before he had a chance to join the conflict. In 1976 he recalled, “Most of the town’s young men who were two or three grades ahead of me got wiped out in the air force, and all the younger ones were very eager to go and get wiped out too. There is something about a death wish—I don’t know anything about that, but I do know that it was going to be a terrible disgrace for me if I didn’t get in the war.” In December 1944, Ewen was assigned to a reconnaissance regiment scouting out enemy troops on the Western Front but saw no action. He was decommissioned after the war, but as a veteran he qualified for an allowance of $120 a month as long as he was in school.

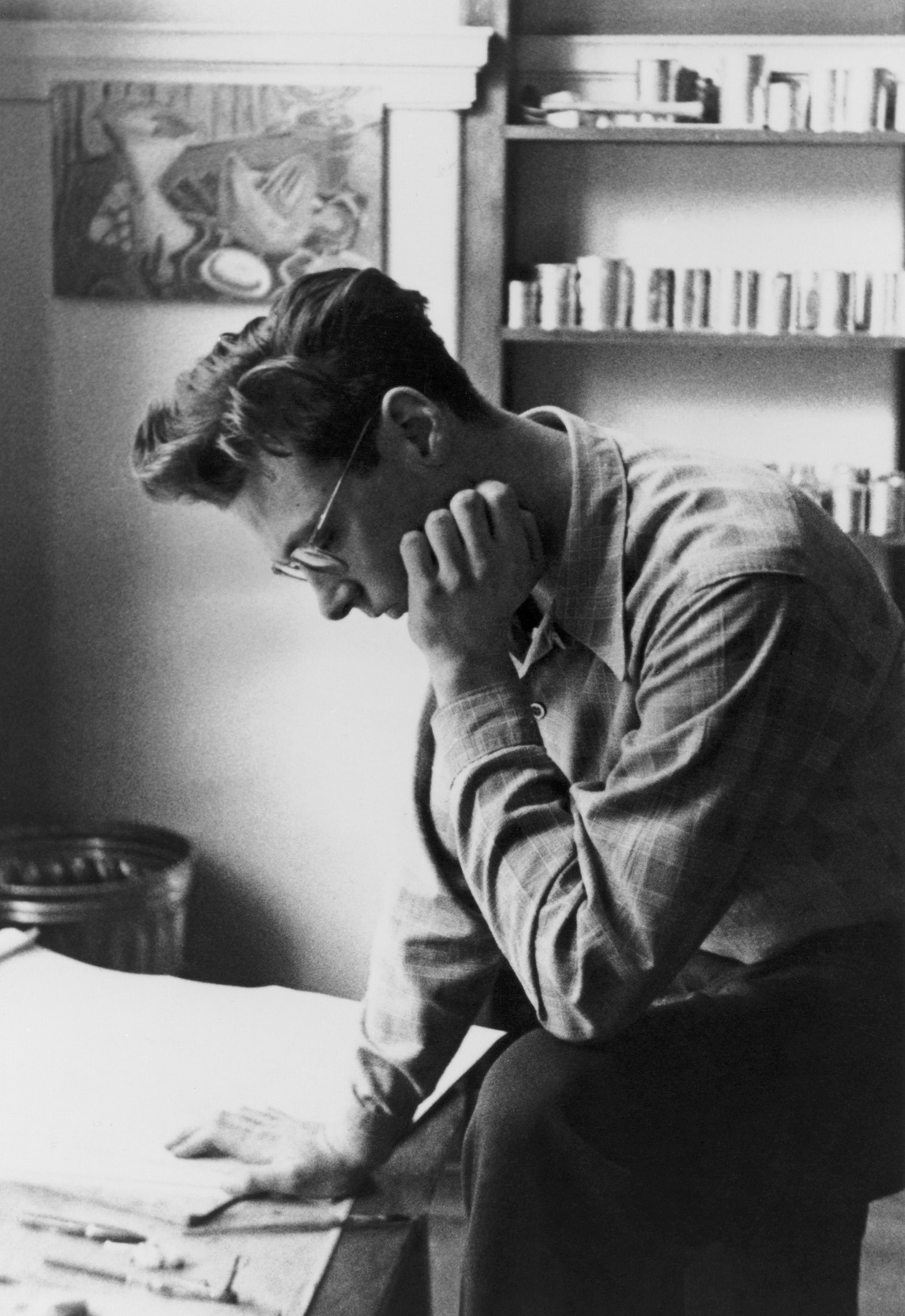

In June 1946, therefore, Ewen enrolled in a Bachelor of Arts program at McGill University in Montreal, where he declared a science major because of his fascination with geology. Ewen barely passed his first year of university because he was struggling with depression, and over the summer he joined the Canadian Officers Training Corps at Saint-Gabriel-de-Valcartier near Quebec City, with the idea that he might re-enlist full-time. Had he not taken up drawing and painting, his future might have been very different.

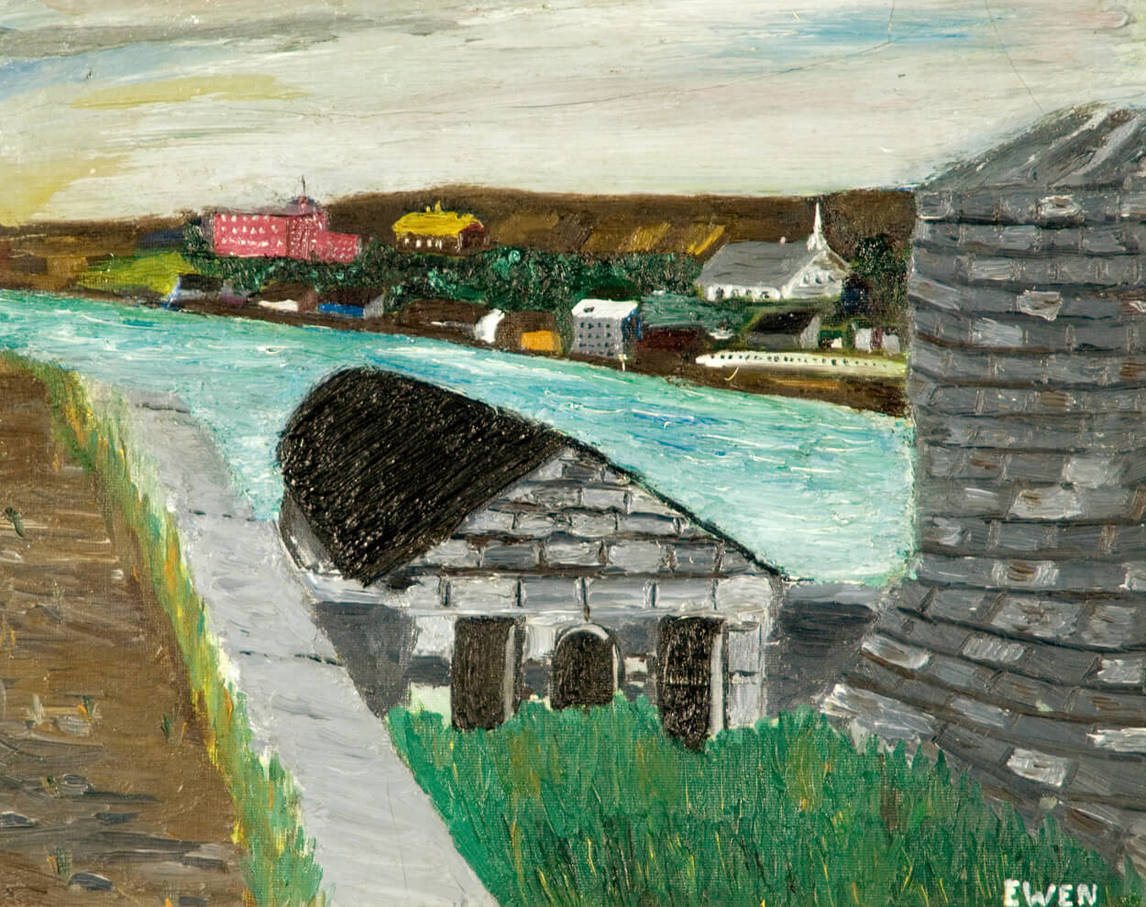

Ewen started by copying magazine covers, then sketched the landscapes in and around Quebec City. He eventually bought some paints and produced Citadel, Quebec, 1947, and Landscape with Monastery, 1947, his first two works, both figurative, as all of his output would be until the end of 1954. Although naive in style, they demonstrate potential for an artist who was essentially self-taught to that point. Having possibly found his vocation, Ewen transferred that fall to the Bachelor of Fine Arts program at McGill, where he enrolled in a figure-drawing course taught by John Lyman (1886–1967). The American-born artist was influenced by Henri Matisse (1869–1954) and the Fauves in France, and although Lyman’s style was more restrained, lacking the striking colours and contrasts of Matisse and the Fauves, his paintings were poorly received by Montreal audiences and critics. Despite Lyman’s desire to introduce modernism to Canada, his star was on the decline when he started teaching at McGill, and his students bore the brunt. As Ewen noted: “I decided to become an artist. I prepared myself for the worst—and it came … Lyman was a nasty person and I think he may have been jealous of me as the only other man in the room.”

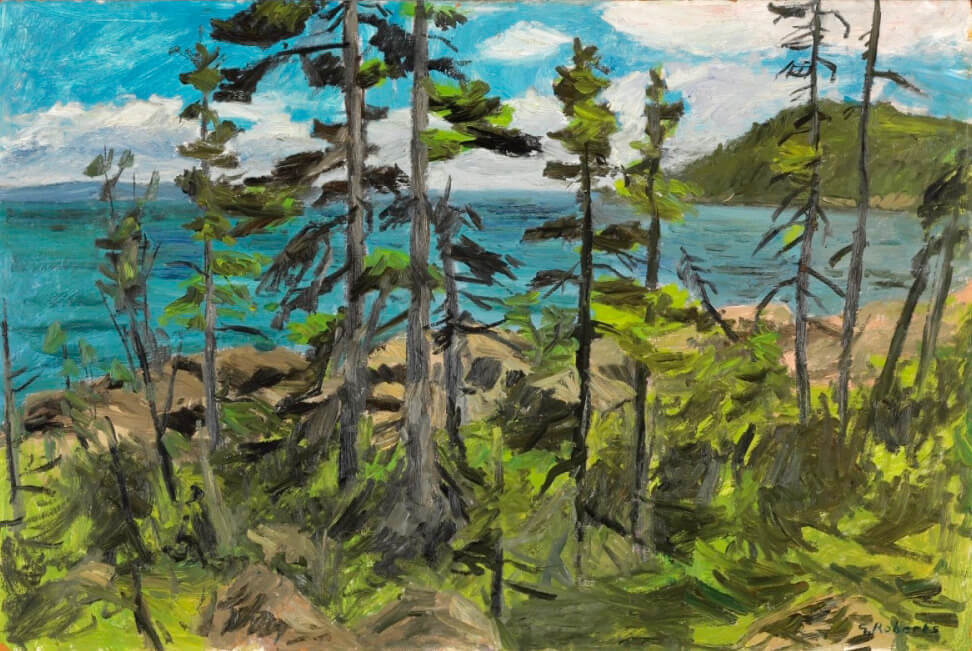

Ewen went to the dean who, he recalled years later, told him, “We have enough people around the university who are just here because everybody else is, or they don’t know what else to do, and if you have this keen interest in art … why don’t you go and study art?” On the dean’s recommendation, Ewen transferred to the Montreal Museum School of Fine Art and Design, which was headed by Group of Seven artist Arthur Lismer (1885–1969) and offered sculpture, painting, drawing, printmaking, and commercial design. There Ewen found an environment that suited him, “a very sympathetic atmosphere,” as he put it, “the happiest days of my life.” Among the teachers were strong figurative artists such as Lismer, Marian Scott (1906–1993), Jacques de Tonnancour (1917–2005), Moses “Moe” Reinblatt (1917–1979), and William Armstrong (1916–1998). Ewen became particularly attached to Goodridge Roberts (1904–1974), whose “movie star aura,” eccentric behaviour, and mental health struggles drew Ewen to him. In his paintings, particularly the landscapes, Ewen adopted Roberts’s loose, rapidly applied brushstrokes and his teacher’s preferred vantage points when selecting scenes. Ewen occasionally painted with Roberts on class outings. Although their vantage points and techniques are similar, Ewen’s palette tends to be brighter and more intense.

Goodridge Roberts, Trees, Port-au-Persil, 1951, oil on canvas, 60.7 x 91.5 cm, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa.

Bridging the Two Solitudes

In the spring of 1949, Ewen attended a talk where he met Françoise Sullivan (b. 1923), a painter, dancer, and member of the Automatistes, a group of avant-garde Québécois artists. Ewen was completely taken by Sullivan, and she by him. Soon she introduced him to other Automatistes. Inspired by the Surrealists, they had released the Refus global in 1948. The manifesto declared freedom by using the subconscious as a tool of liberation from the oppression of the Roman Catholic Church and the traditionalist conservative politics of Quebec premier Maurice Duplessis. These had dominated the political landscape from 1936 to 1959, a period referred to as La Grande Noirceur (The Great Darkness). Artistically, the Automatistes sought to develop an abstract language of the subconscious that avoided the perceived ineffectiveness of figurative analogy, just as the Abstract Expressionists were attempting to do in the United States.

“I integrated into the French side without completely losing the English side,” said Ewen, who another time explained, “I don’t have a flair for languages, so I would sit without taking part in the conversation all that much, but of course it was very enriching.” As can be seen in Portrait of Poet (Rémi-Paul Forgues), 1950, the influence of the Automatistes on Ewen’s work is not obvious at first; his work remains figurative. However, stylistically his brushwork becomes far looser, to the point that one strains at times to identify specific objects in a scene, and he begins to experiment with colour combinations and contrasts that recall those in the abstract paintings of the French Canadian artists. The Automatistes recognized this affinity, writing favourably about Ewen’s figurative paintings and inviting him to exhibit with them.

By the fall of 1949 Sullivan was pregnant, and she and Ewen married in December. The following year, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts chose two of Ewen’s works for its 67th Annual Spring Exhibition, held in March. The jury, however, rejected all of the Automatistes’ submissions, except one by Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960). The group countered with its own show, L’Exposition des Rebelles, which included a couple of Ewen’s landscapes. Borduas and Ewen were the only artists represented in both exhibitions, and these were the first public showings of Ewen’s art. What should have been a time of great joy for Ewen—with works in two high-profile shows and the birth of his first son, Vincent (b. 1950), named for Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890)—suddenly turned difficult. As Ewen later recounted, “Lismer … came up to me towards the end of the second year and he [handed] me the diploma, and said, ‘There’s no point in you hanging around an art school anymore. It’s obvious you’ve decided to be a painter.’” Ewen’s veteran’s allowance would automatically be cut off—which meant he had to find a job, and quickly.

After a few months working in a hat factory, Ewen was hired at Ogilvy’s department store as a rug salesman. The work left him very little time to paint, but he did manage to pull together his first solo exhibition in May 1950 in the rented basement of a store on Crescent Street. He sold most of the work. The show, which included a range of early works from Landscape with Monastery, 1947, to Bay in Red, 1950, was reviewed favourably in the Montreal Herald and Le Devoir. Soon Ewen’s father-in-law, John Sullivan, contacted his old friend Maurice Duplessis, who found the two of them municipal jobs at the rent control board. Ewen ended up earning a healthy salary of $3,000 a year as the assistant secretary to the chief administrator—his father-in-law. The irony, of course, was that Ewen got his job from the politician the Automatistes despised the most, who embodied all that they believed was wrong with Quebec at the time. Nonetheless, the position provided some much-needed financial security for the artist, though there were few exhibitions, at least until 1955.

Abandoning the Figurative

Ewen painted his first abstract work near the end of 1954. His involvement with the Automatistes certainly contributed to his move away from the figurative, though he could never paint as spontaneously as they did since he always needed structure to form his images. Nor could he fully embrace the hard-edged geometric canvases of the Plasticien painters, led by Guido Molinari (1933–2004). Nevertheless, or maybe because of this, Ewen moved fluidly between the waning Automatistes and the emerging Plasticiens. He showed his abstract work for the first time publicly at Espace 55, organized by Claude Gauvreau (1925–1971) at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Soon afterwards he exhibited at Molinari’s newly opened Galerie L’Actuelle, and he became a founding member of the Non-Figurative Artists’ Association of Montréal that Molinari helped create in February 1956. Ewen also got his first one-man show outside Montreal, at the Parma Gallery in New York. The reviews were positive, though most identified his work as derivative of Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) and Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944).

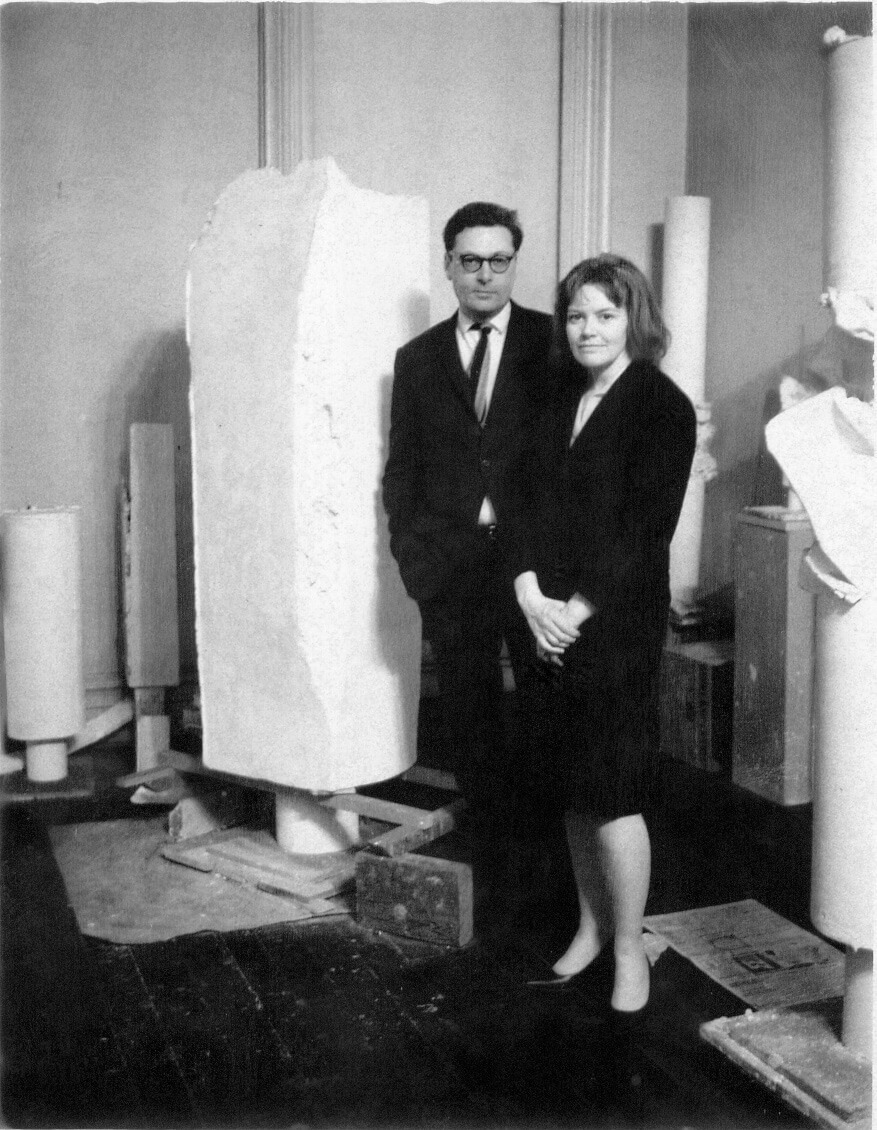

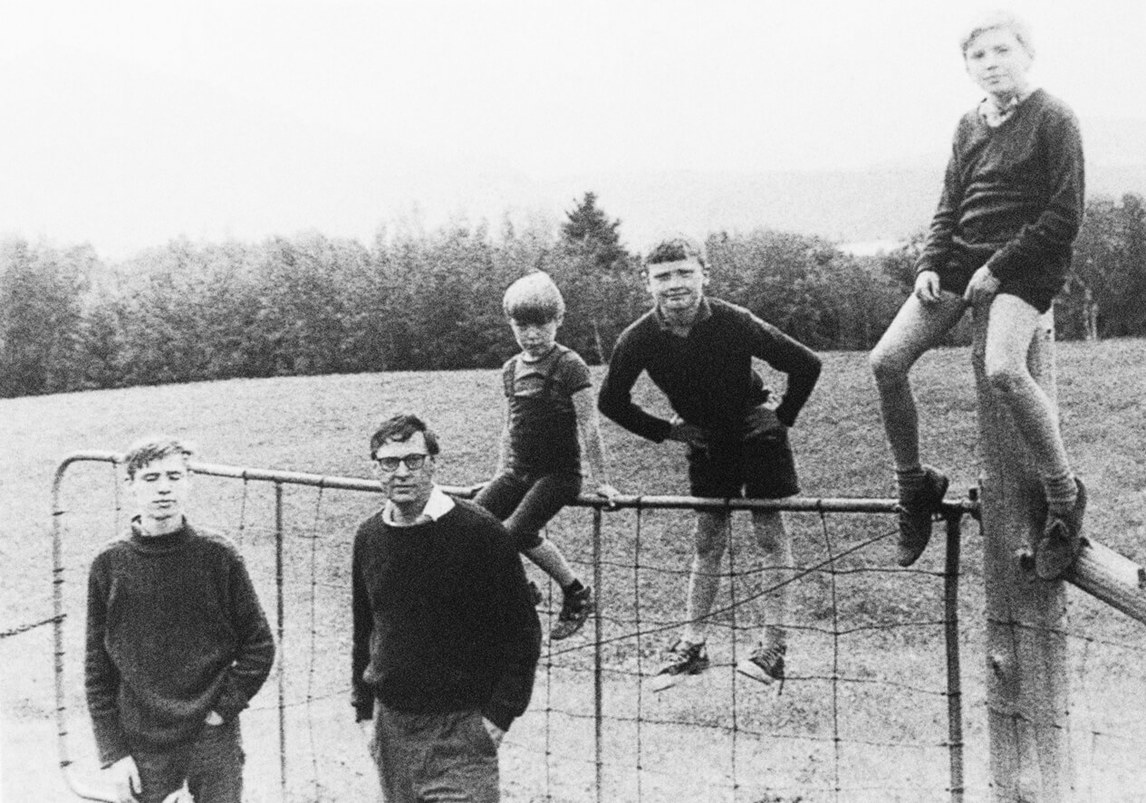

In the winter of 1956 Ewen took a job as an employment supervisor at Bathurst Containers. Sullivan had just given birth to their second son, Geoffrey (b. 1955), and Jean-Christophe (b. 1957) and Francis (b. 1958) were soon to follow. Over the next ten years Ewen’s artistic output was limited but nevertheless impressive. He continued to exhibit regularly, including in many solo shows. In August 1957 he was awarded second prize for painting in the Concours artistiques de la province de Québec, an important province-wide competition. The following year the Galerie Denyse Delrue hosted an exhibition of Ewen’s work, which it continued to do almost every year until 1963, when Ewen’s productivity dropped dramatically due to a promotion at Bathurst. In fact, the years between 1958 and about 1965 were punctuated by a variety of experiments in painting, perhaps because he could not devote himself to his vocation full-time or because he had yet to find his artistic voice.

In the summer of 1958 Ewen visited Toronto and was mesmerized by Northwest Coast artifacts at the Royal Ontario Museum, which fuelled memories of his father’s stories about living in the north while working with the Hudson’s Bay Company. Ewen describes the inspiration for his first Lifestream paintings, a series of abstract works emphasizing movement along the horizontal: “I was just thunderstruck by the designs along the sides of the canoes and … it seemed like insignia or stylization of the Haida … [I] went back and did a few paintings at least somewhat influenced by them.” By the summer of 1961 he was working on his Blackout series, large monochrome paintings that evoke the night sky and may have been inspired by the black and white paintings of Borduas, such as The Black Star, 1957. Ewen talked about a visit to Borduas in New York: “He had got rid of the figure-ground distinction. He was doing white paintings, with black … and they were great.… Later he was doing monochromes and they were works of genius.”

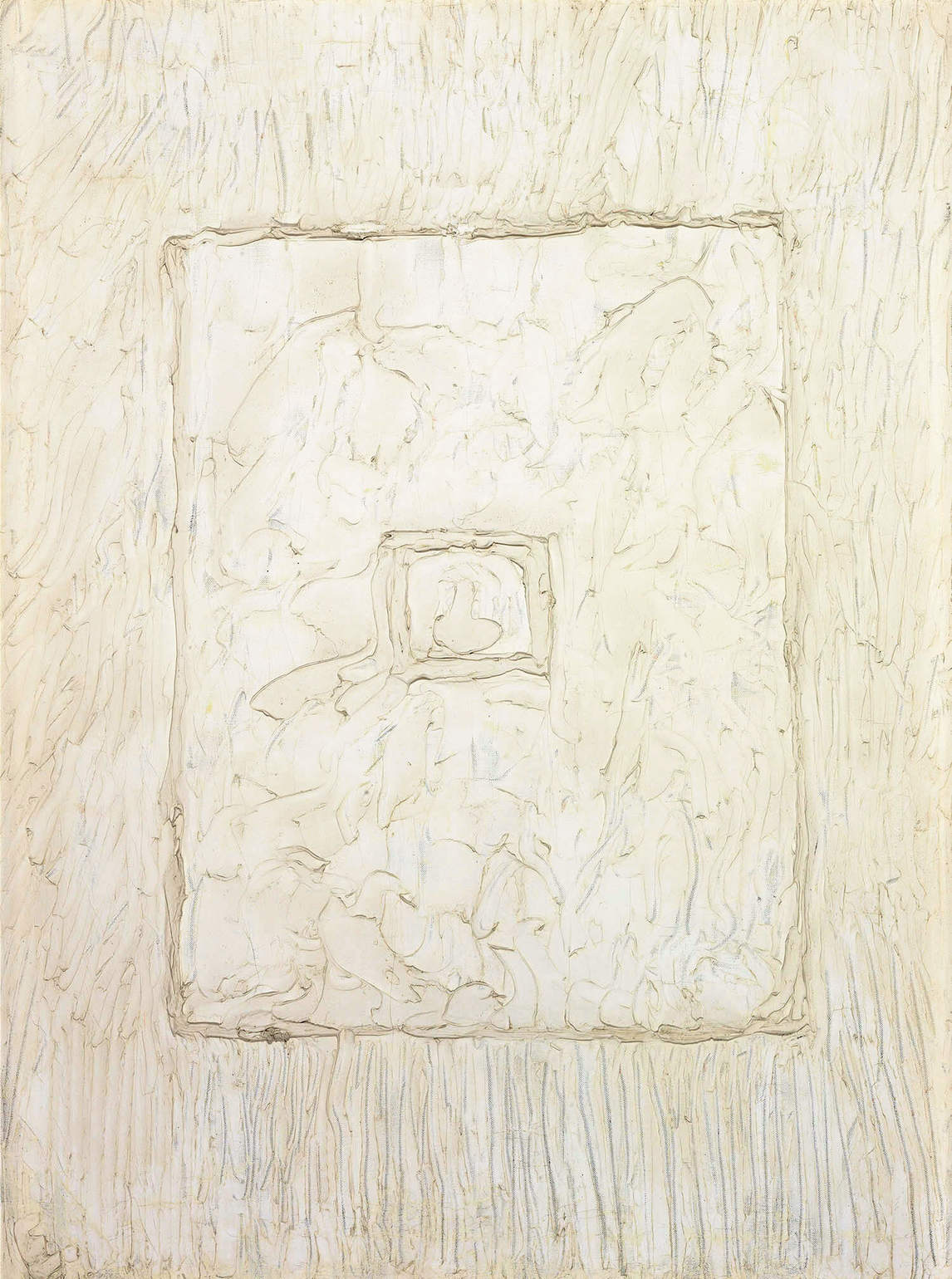

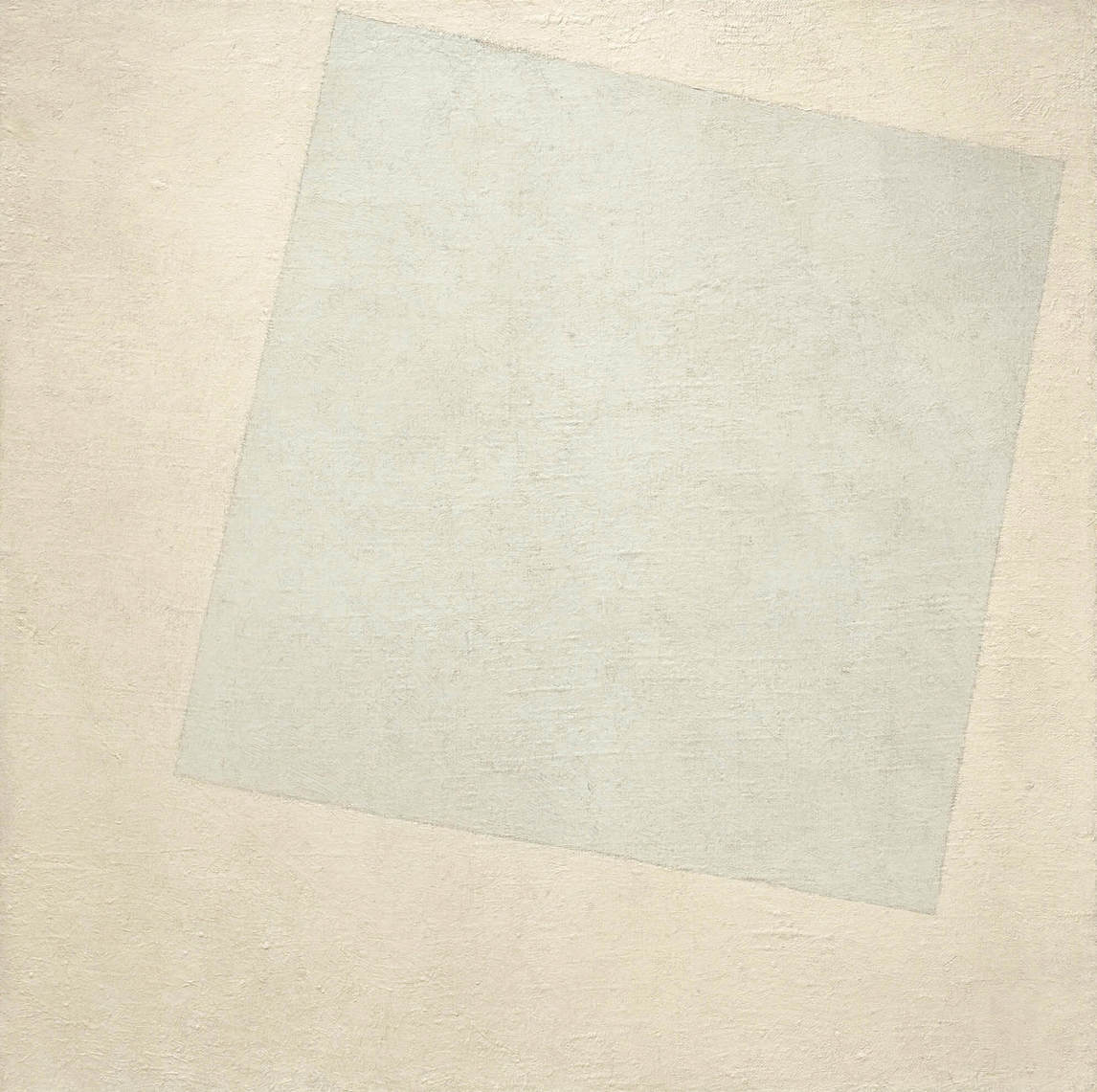

In 1962 Ewen produced a curious series of pastels on paper, including Untitled, 1962, in response to reading The Great Experiment: Russian Art, 1863–1922, a seminal text on modern Russian art by the British scholar Camilla Gray, which had just been published. Gray’s study was especially notable for its discussion and reproduction of a range of works from the 1910s and 1920s, long suppressed with the rise of Stalinism and largely unknown. Ewen’s white abstractions, such as White Abstraction No. 1, c. 1963, may have taken their lead from the White on White series of Kazimir Malevich (1878–1935), one of the earliest-known artists to produce monochromes, as well as further acknowledging Borduas’s late work. However, the American Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), the French artist Yves Klein (1928–1962), and the Italian Piero Manzoni (1933–1963) were producing similar works in the 1950s and early 1960s, and Ad Reinhardt (1913–1967) was painting dark monochromes, which Ewen records having seen in New York in the late 1950s.

Paterson Ewen, Untitled, 1962, oil pastel on paper, 66.2 x 47.7 cm, Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal.

For his monochromes and Russian Constructivist–inspired works, Ewen was awarded a Canada Council fellowship in 1964, which funded a turn to geometric paintings that would adopt a variant of the hard-edge style of the Plasticiens. Ewen recalled: “[Claude] Tousignant was doing targets and Molinari was doing vertical stripes and I was doing neither of those things. But … sharing a studio with both of them … I picked up the technique … of how to lay on paint and how to get a perfect line. Molinari was fanatic about that.” Turning to a geometric style was certainly a way of seeking control at a time when Ewen’s crumbling family life was resulting in increased personal struggles, as suggested by such works as Diagram of a Multiple Personality #7, 1966.

Ewen’s Grande Noirceur

By November 1966, Ewen and Sullivan formally separated. Ewen’s response was to work and drink more heavily and to experiment with a bohemian lifestyle that finally caught up with him when he was fired from his job at RCA Victor, one of a series of jobs he got after leaving Bathurst Containers. Shortly thereafter, he sold five large paintings to Ben and Yael Dunkelman, who owned the Dunkelman Gallery in Toronto. Although they gave him two shows, one a solo exhibition, this success did not prevent Ewen from falling into a deep depression. He made visits to Montreal’s Royal Victoria Hospital, where he was treated for acute depression, and to the Queen Mary Veterans Hospital, also in Montreal, where he received a controversial treatment known as insulin shock therapy. The therapy induced a brief coma and caused seizures that appeared to have a beneficial effect on mental health patients. Ewen felt the treatment worked in his case.

With his life spinning out of control, Ewen was invited to stay with his sister, Marjorie, and her husband in Kitchener, Ontario, in the summer of 1968. Unfortunately, his depression worsened to the point that he stopped talking and making art. Marjorie sent him to her psychiatrist who recommended Ewen admit himself immediately to the Westminster Veterans Hospital in London, Ontario, where at the end of the summer he submitted himself to electroconvulsive therapy. This yielded encouraging results: “The treatment did me a lot of good … I came out of there in a state of good physical and mental health.” He had thoughts of returning to Montreal and rejoining his wife and family, but his doctor strongly advised against it. Ewen decided to settle in London.

The London Years

In London, Ewen picked up his Lifestream series again, working with colour fields and his looser variant of the hard-edge style. Almost immediately, he was introduced to the city’s vibrant art scene, led primarily by Greg Curnoe (1936–1992), who had visited Ewen during his stay at Westminster. As well, Doreen Curry, a friend of Ewen’s sister, took him to the London Public Library and Art Museum to see the Heart of London exhibition organized by the National Gallery of Canada, which showcased the work of the London Regionalists. Although the London artists embraced him, Ewen did not become a part of the various cliques that formed, for example, around Curnoe and Don Bonham (1940–2014). As was the case in Montreal, Ewen made friends with everyone and antagonized no one, but he remained fiercely his own person; he was highly adaptable without ever being co-opted. The London Regionalists were known for their willingness to experiment and for their emphasis on materiality, and their influence on Ewen is evident in such pieces as Rocks Moving in the Current of a Stream, 1971.

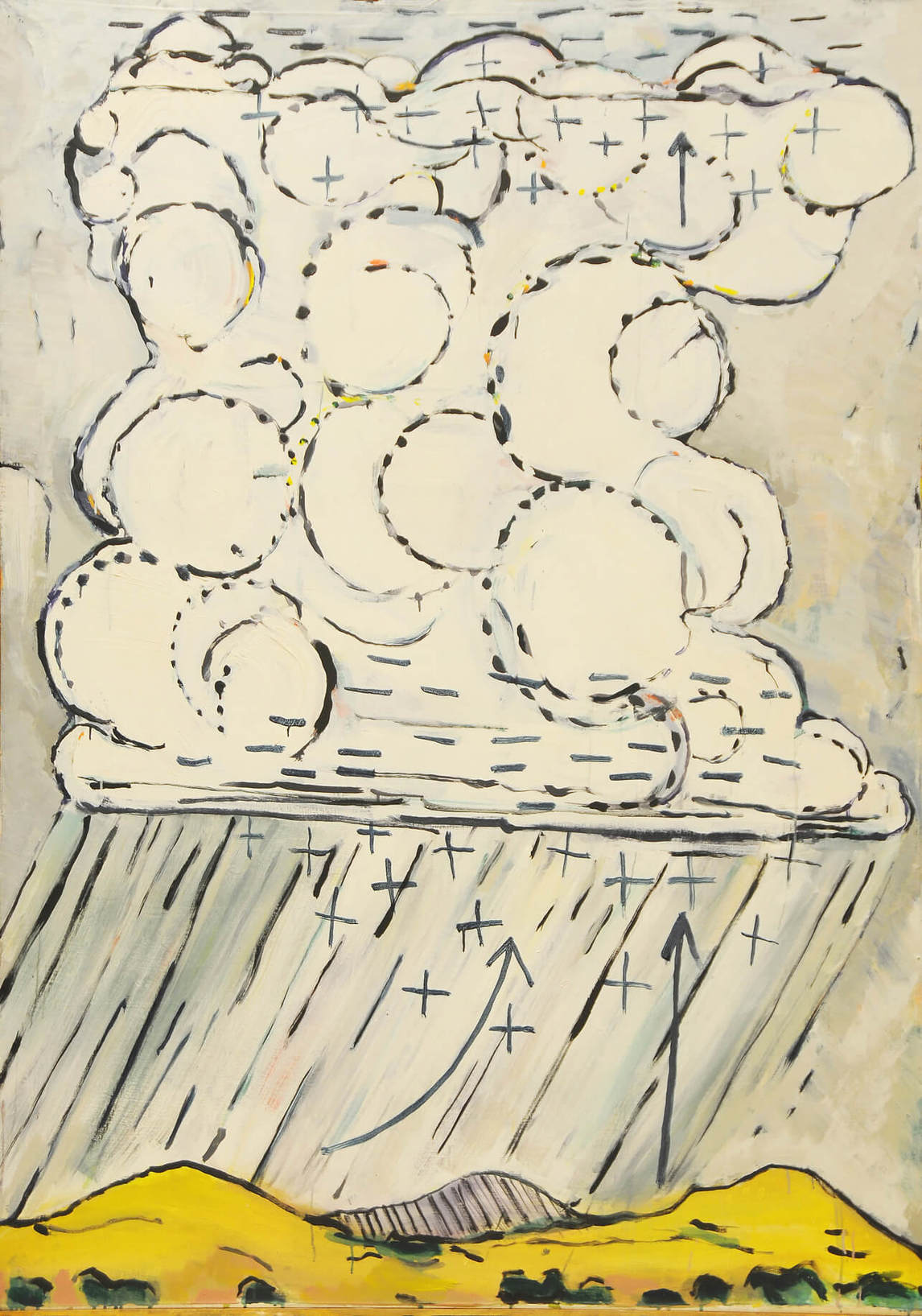

On the recommendation of the abstract painter David Bolduc (1945–2010), Ewen joined Toronto’s Carmen Lamanna Gallery in 1969. Subsequently, he was hired as a teacher at the H.B. Beal Secondary School in London, a position he held until the spring of 1971, which allowed him to focus fully on his artwork. Around late 1970 or early 1971, Ewen purchased a piece of felt while helping with arrangements for the Pie in the Sky group show that opened in March 1971 in Toronto. Instead of using his brush, he tried dipping pieces of the felt in paint and dabbing them across a gessoed canvas. He later stated, “What do you do for an encore, once you have a colour field and a single line. You either repeat yourself endlessly or you go into something else.” The result of this artistic experiment was Traces through Space, 1970, a transformative work whose rows of dots suggested to Ewen rain and other natural phenomena. Several subsequent pieces show, in various ways, different weather and celestial phenomena. He had essentially returned to where he had started—landscape—though the works were newly informed by old scientific texts and expanded beyond the terrestrial. Several of these works, including Drop of Water on a Hot Surface, 1970, were presented at the Pie in the Sky exhibition.

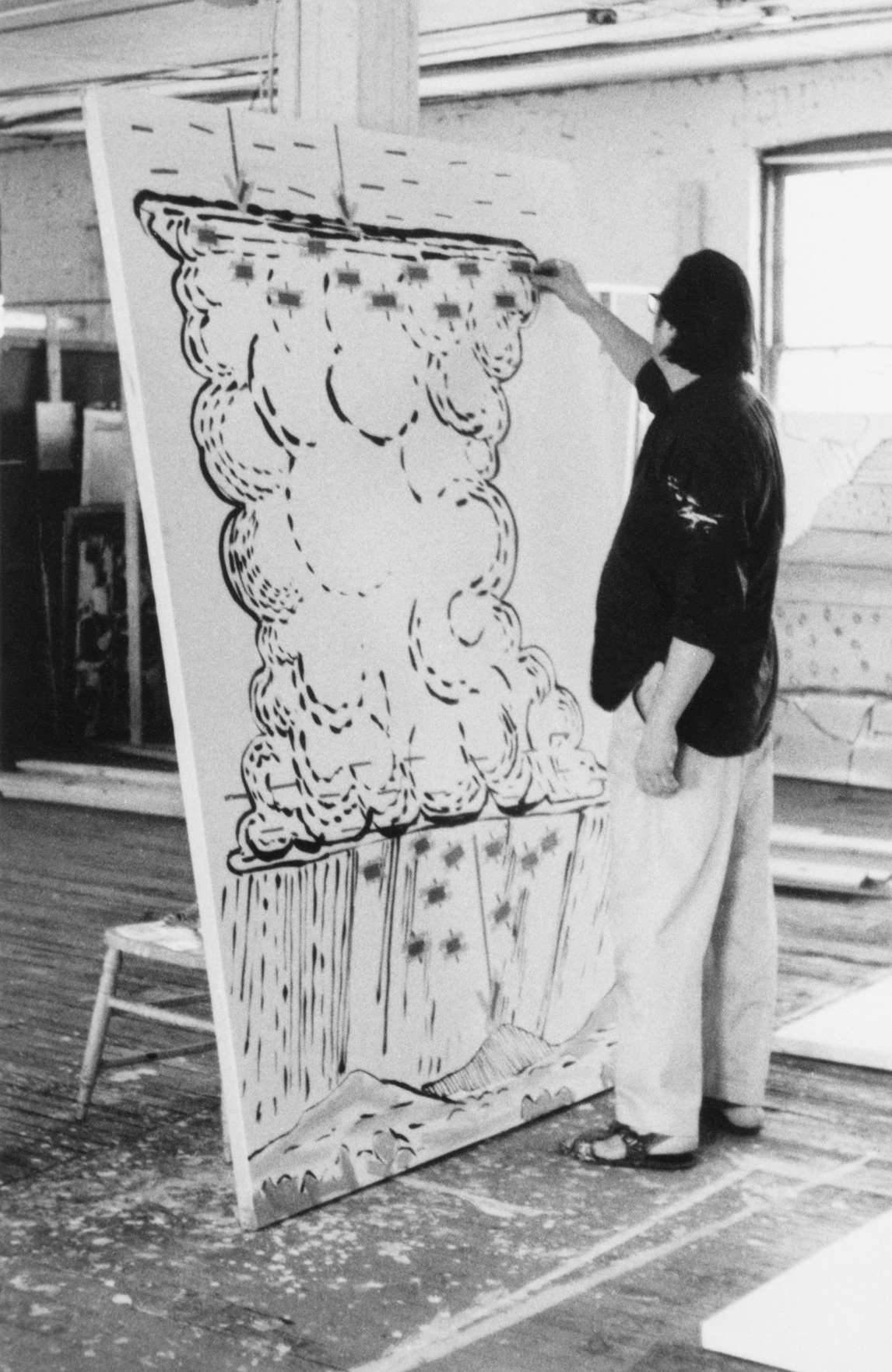

Having received a senior Canada Council grant in June 1971, Ewen took a leave of absence from teaching at Beal and spent time living and working in Toronto. He began working with standard sheets of four by eight by three-quarter inch plywood with the idea of producing a massive woodcut print like those of the Japanese artists he had admired since childhood. As he told Nick Johnson in a 1975 interview, “I was sick of canvas and stretchers and paint.” First he used hand tools to carve the plywood, but while rolling the paint onto the board on his first attempt he realized that he had devised a new type of painting. Instead of creating a print, he decided to simply display the painted, carved plywood as a painting. Eventually Ewen exchanged hand tools for an electric router and, as he put it: “I enjoyed the physicality of it, particularly after the meticulousness of the hard-edge painting. It was like a kind of therapy. I may not have felt the tension and anger pouring out of me when I did it, but it felt awfully good afterwards.”

As he was about to return to teaching at Beal, Ewen was advised that his position had been assigned to someone else. However, as luck would have it, the University of Western Ontario’s Department of Visual Arts was looking for a painting instructor to replace Tony Urquhart (b. 1934). Ewen was initially made a lecturer and eventually a full professor with tenure, which gave him his own studio, time to paint, and, with financial security, the stability he had craved since leaving Françoise Sullivan. Though he was still struggling with depression, and he continued to drink on and off again, he began to experience a measure of success. In 1973, he finally sold out a solo show—his third with the Carmen Lamanna Gallery—and to buyers that included the National Gallery of Canada, the Canada Council Art Bank, and the Art Gallery of Ontario. He was starting to become recognized as a major player on the Canadian art scene.

The late 1970s and early 1980s were a golden era of art for Ewen. He met Mary Handford, who would become his second wife in 1995, at the University of Western Ontario (now Western University) in 1979. They travelled to Paris and Barcelona together in 1980, the first of many trips that proved to be a continuing source of inspiration for Ewen. He absorbed new influences ranging from the work of J.M.W. Turner (1775–1851) to Claude Monet (1840–1926) to Georges Seurat (1859–1891) while also revisiting some old favourites such as Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847–1917) and Vincent van Gogh. His early experiments with landscapes and gouged plywood blossomed into the striking celestial works and powerful earthly scenes that have etched Ewen’s name in the annals of Canadian art.

Paterson Ewen, Lethbridge Landscape, 1981, acrylic on plywood, 243.8 x 487.7 cm, University of Lethbridge Art Gallery.

From that point on, his career was marked by a series of important exhibitions; guest lectures; visiting-artist stints (for example, at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design and the Banff School of Fine Arts); and by awards and recognitions that included being elected to the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts in 1975, representing Canada at the Venice Biennale in 1982, and receiving Honorary Doctor of Laws and Letters degrees from Concordia University in Montreal and University of Western Ontario in London in 1989, as well as the Jean A. Chalmers National Visual Arts Award in 1995 and the Gershon Iskowitz Prize in 2000. This success was marked by a major solo exhibition curated by Matthew Teitelbaum at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) in Toronto in 1996. The AGO made a commitment to collect Ewen’s work after it received a substantial donation of his paintings from Richard and Donna Ivey, important art collectors and philanthropists from London, Ontario, and from Ewen himself. Ewen was the first contemporary artist to be so honoured by the Toronto institution. Possessing the largest and most comprehensive collection allowed the AGO “to refer to itself as the study centre of Paterson Ewen’s work,” as the chief curator at the time, Matthew Teitelbaum, announced.

Ewen’s achievements were clouded by his depression. Mary Handford took up residence with Ewen in 1980, but tensions arose as she moved to Waterloo, Ontario, to pursue an architecture degree. Ewen had trouble dealing with the long-distance relationship. In 1986, he checked himself into an alcohol treatment centre. Not only was he forced to stop drinking, but he was also denied the anti-anxiety and antidepressant drugs that other doctors had prescribed and on which his body had grown dependent. At a time when he should have been celebrating the success marked by two major shows of his work, at the Mendel Art Gallery in Saskatoon and the Art Gallery of Ontario, he was instead made to take early retirement from the University of Western Ontario as a consequence of his illness.

Only after Handford came back into his life in 1988 did Ewen recover somewhat. He did, however, suffer another major setback after undergoing surgery in 1992. The operation itself went well, but he was taken off his usual medication, which, again, severely affected his mental health. He was admitted to the psychiatric ward at the Old Victoria Hospital in London, where it took about six months to find a combination of antidepressants to restore Ewen’s health. During this period, he lost a lot of weight, which left him physically weak. His ongoing medical issues and advancing age were taking their toll, and his ability to work with the router became more limited.

Ewen persisted, however, and found ways to fuel his rich imagination. For example, when he accidentally cut through a sheet of plywood, he created a new body of work, including Satan’s Pit, 1991, in which he intentionally bore holes into the plywood to represent everything from the mouth of hell to celestial bodies. He used watercolour on handmade paper to parallel the gouged look of his plywood paintings. He incorporated materials such as nails, lead, livestock fencing, and even crushed pastels on paper in a new series of drawings. And he continued to produce his large plywood works with the help of his occasional assistant, Iain Turner (b. 1952). Ewen may have created fewer large works during his later years, but his output did not diminish, and the number of exhibitions that included his work grew substantially. Much of this was made possible by his wife, Mary, who was a constant and diligent supporter of Ewen’s work, whether helping him find supplies or through her photography, and she was an invaluable companion whom Ewen cherished. Ewen’s health, though, finally gave way and he died at home in London on February 17, 2002, with Mary by his side.

Paterson Ewen, 1996, photograph by Ken Faught, Toronto Star Photograph Archive.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements