Ozias Leduc is one of the first Canadian artists who can be seen as a philosopher. All his artworks are attempts to arrive at a response to the questions that drove his artistic mind: questions about the role of the artist, and about the cultural and social mission of art. Educated in the nineteenth century and active into the 1950s, Leduc created traditional art. And yet, he impacted each generation of artists with whom he engaged. His long and prolific career can be separated into two main bodies of work: church paintings and religious commissions that existed on the fringes of the Canadian art world, and easel paintings that were greatly in demand by a circle of the country’s art lovers. Although influenced by his immediate environment and those around him, Leduc distanced himself from his contemporaries in order to define his personal values and autonomous creativity.

A Personal Definition of Art

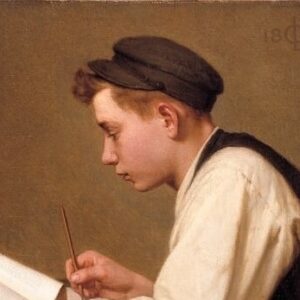

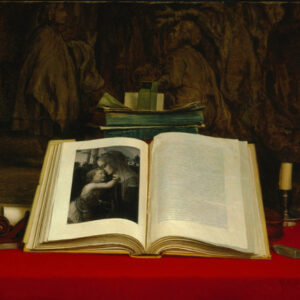

In Ozias Leduc’s practice, painting was a reflection on the nature of a work of art, its purpose, and its effect. The results of these interrogations are inscribed directly within his paintings. He evokes the process of creation, depicting the formal components and iconography of a work, such as in Phrenology (La phrénologie), 1892, or Still Life with Lay Figure (Nature morte dite “au mannequin”), 1898; or investigates a work’s reception, as in Boy with Bread (L’enfant au pain), 1892–99, The Young Student (Le jeune élève), 1894, and The Millworkers (Les chargeurs de meules), c.1950. These works and many others reflect the function of art as a way of learning about the self and nature, and how they are received and interpreted by each individual.

Throughout his long career Leduc also addressed these matters in written reflections, ceaselessly questioning the meaning and scope of his own production and that of others. He believed that art is a need; it provides the light and energy necessary to life. In his church decorations he presented elements that would impact the life of a Christian. In the Church of Saint-Hilaire, for instance, he represented the seven sacraments (The Baptism of Christ [Le Baptême du Christ]), 1899); in his still lifes and landscapes he composed interiorized scenes of emotional experience (Mauve Twilight [L’heure mauve]), 1921. In all of his work Leduc sought to touch and move the viewer with an approach that emphasized harmony and unity.

Through his art and writings we learn that Leduc understood creation as a process of constant effort. He aimed to interpret what he learned from nature, which was the source of all his work. For Leduc art is labour, a combat in which the intellect must battle its environment: “To apply yourself with all your strength to hard, necessary work, that is the making of Art. It is the struggle between thought and the rebellious material of the world. It is through struggle that a human being perfects his intelligence and penetrates ever deeper into the order of Nature.” The systems of nature are in his view governed by laws that are incumbent upon the artist to discover and explore.

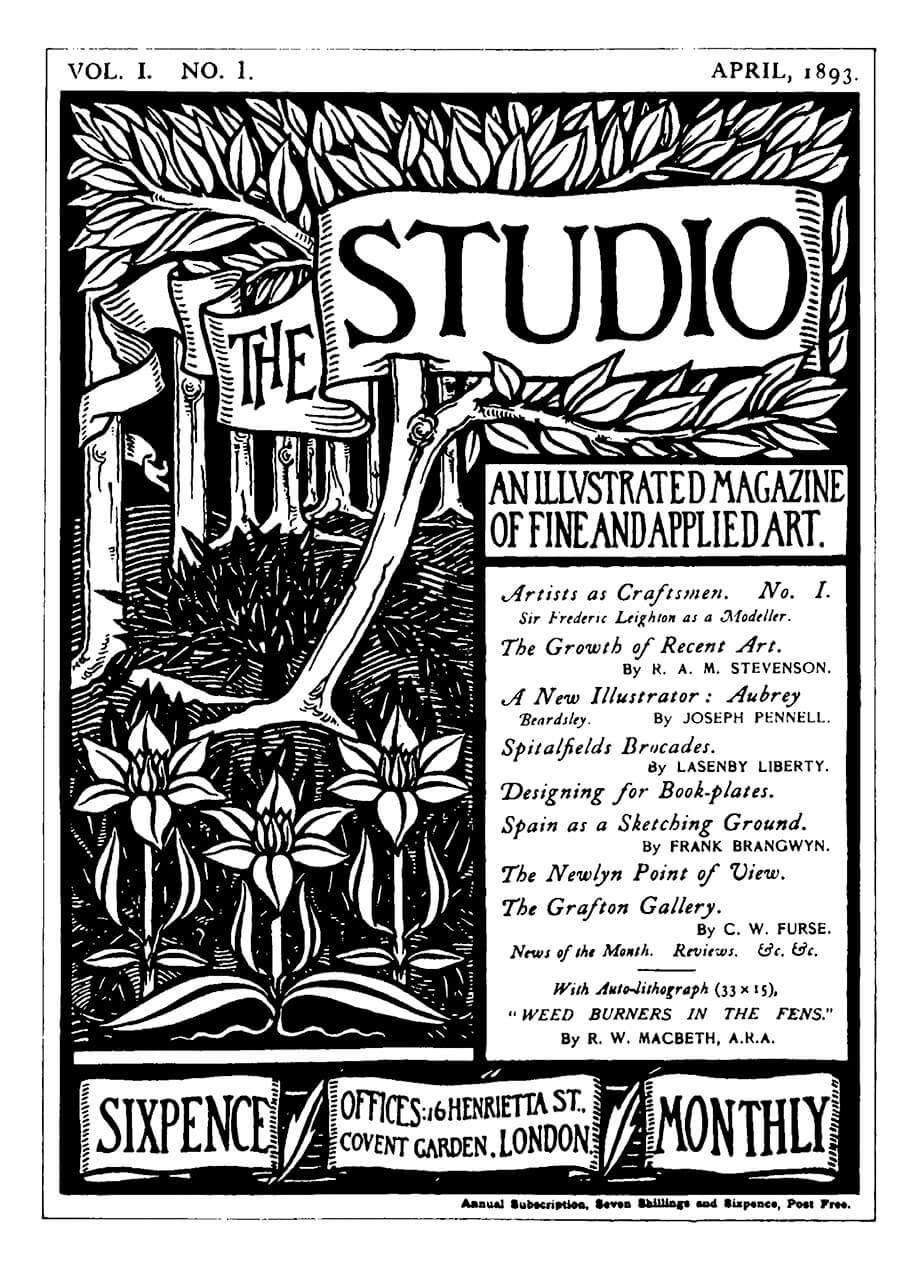

Leduc was influenced by the thinking of British artist William Morris (1834–1896), which was widely disseminated in the journal The Studio. Morris called for a utilitarian art, one that would introduce good taste and intellectual rigour into the design of everyday objects. This was one reason why Leduc invested so much in his decorations of Catholic churches, which at that time were bustling, busy places. He wanted to create, in the spirit of the Arts and Crafts movement, environments that were unified in their iconography, so that all aspects of the decor were in harmony—places where the desire for beauty, contemplation, and reflection was encouraged, such as in the church at Saint-Hilaire. Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960), who was Leduc’s student, said of this connection: “From my birth until the age of fifteen or so, these were the only pictures I was allowed to see. I cannot tell you how proud I was of that single source of pictorial poetry at an age when the smallest impressions penetrate our core and, unknown to us, establish our critical orientation.”

Leduc’s methods were not scientific. But his means, thanks to his imagination and the resourcefulness of his art, enabled him to draw upon the physical universe of the senses to create images of the spiritual world and of the marvellous: “The substance of my creative art comes from the wide open world of dream,” he wrote. “The substance of living imagination, rendered palpable, so to speak, by the signs of a play of lines, forms, colours, which are also substances of the universe . . . thus a somewhat unreal world but visually precise—the incarnation of the subtle, of magic, of the infinite, of contemplation—The contemplation that comes before creation.”

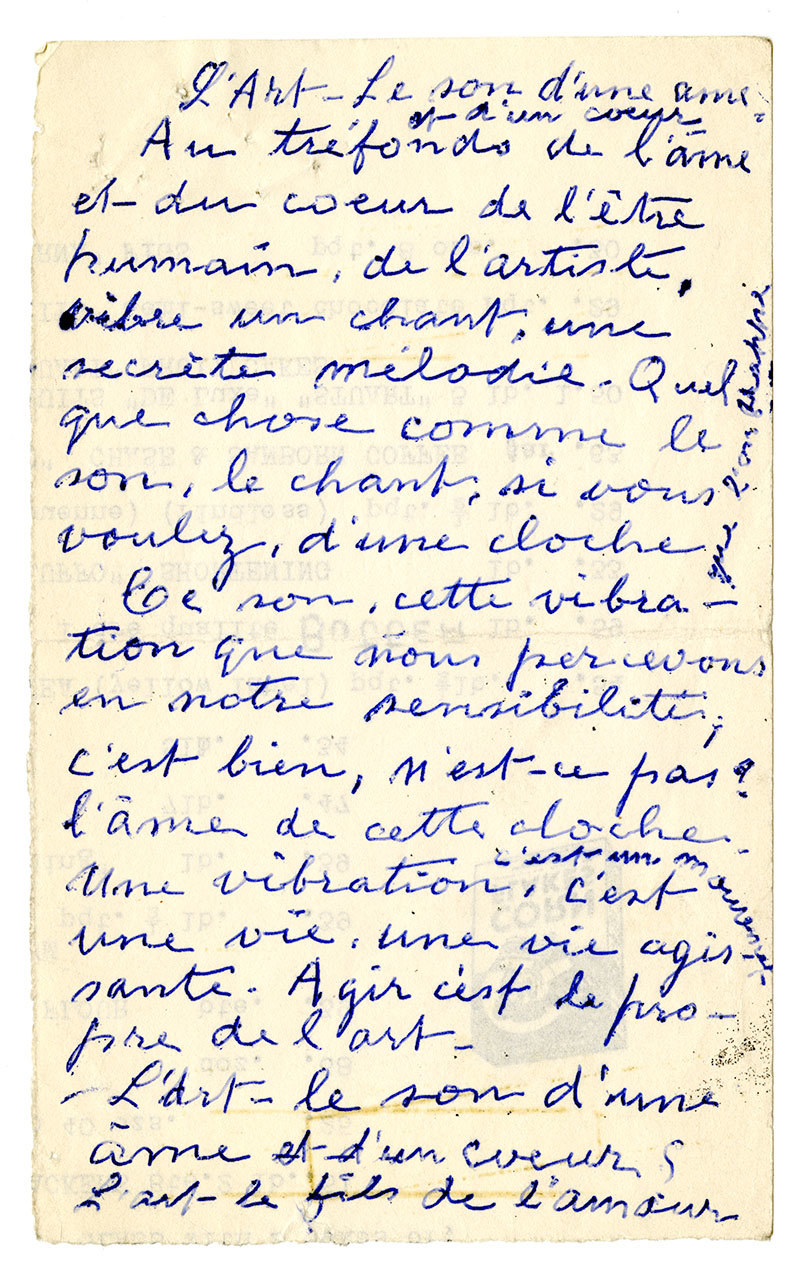

Leduc writes that contemplation must come before creation. Accordingly, the artist must be able to place themselves in this moment—where content is transformed into substance, opening a universe of renewal. Art, he states, exists in the mind of the artist before it is realized, and the resulting artwork is its material form. From this ideal first position, the creator reinvents the world, filling it with new arrangements that transcend time and reveal the primal essence. It is from this suspended view that the artist, even though he is active in a given context, still seeks to situate himself within the infinite, beyond the reach of contingencies and events that might turn him from his quest. “Art, the sound of a soul, of a heart,” he continues. In other words, it is an approach where the imagination and the intellect meet. The force of this encounter resonates outward. The artist, in tune with their senses, understands this tension and taps into it, and from it can project their unique voice. Art proves life and is its ultimate manifestation. By attending to those principles of thought, of action, and of sentiment, art inhabits and makes contact with the deepest recesses of the mind.

A Unique Artist

Leduc’s romantic belief that art was at the centre of life makes him an original personality in Canada. At the very moment he was achieving professional notoriety in the Canadian art world, Canadian art was undergoing a process of transformation. The art world was becoming more consolidated after the emergence of institutions that gave it greater visibility and confirmed the professional status of artists. The Royal Canadian Academy of Arts (1880) and other artists’ associations, the founding of the Art Association of Montreal (1860), the inauguration of art schools offering ambitious programs, and the establishment of important galleries are all indications that an appreciative public was growing, along with an increasingly serious art market. Leduc would receive important commissions as a result, such as his Portrait of the Honourable Louis-Philippe Brodeur (Portrait de l’honorable Louis-Philippe Brodeur), 1901–4, the Speaker of the House of Commons.

Yet at the end of the nineteenth century, foreign and new-immigrant artists—particularly those whose works were collected by or exhibited at the Art Association of Montreal (chiefly British artists or representatives of the Hague School ) or shown in galleries —still produced much of the art in circulation. By the start of the 1890s, however, a new generation of Canadian artists appeared. These were painters who had received their initial training in Canada and had gone on to study in Europe, principally in France. James Wilson Morrice (1865–1924), Maurice Cullen (1866–1934), and Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté (1869–1937) were perhaps the best known of this group. Although they did not participate directly in any of the movements that shook the art world, they retained some of the elements, and brought Impressionism, Symbolism, and Art Nouveau with them when they returned to Canada.

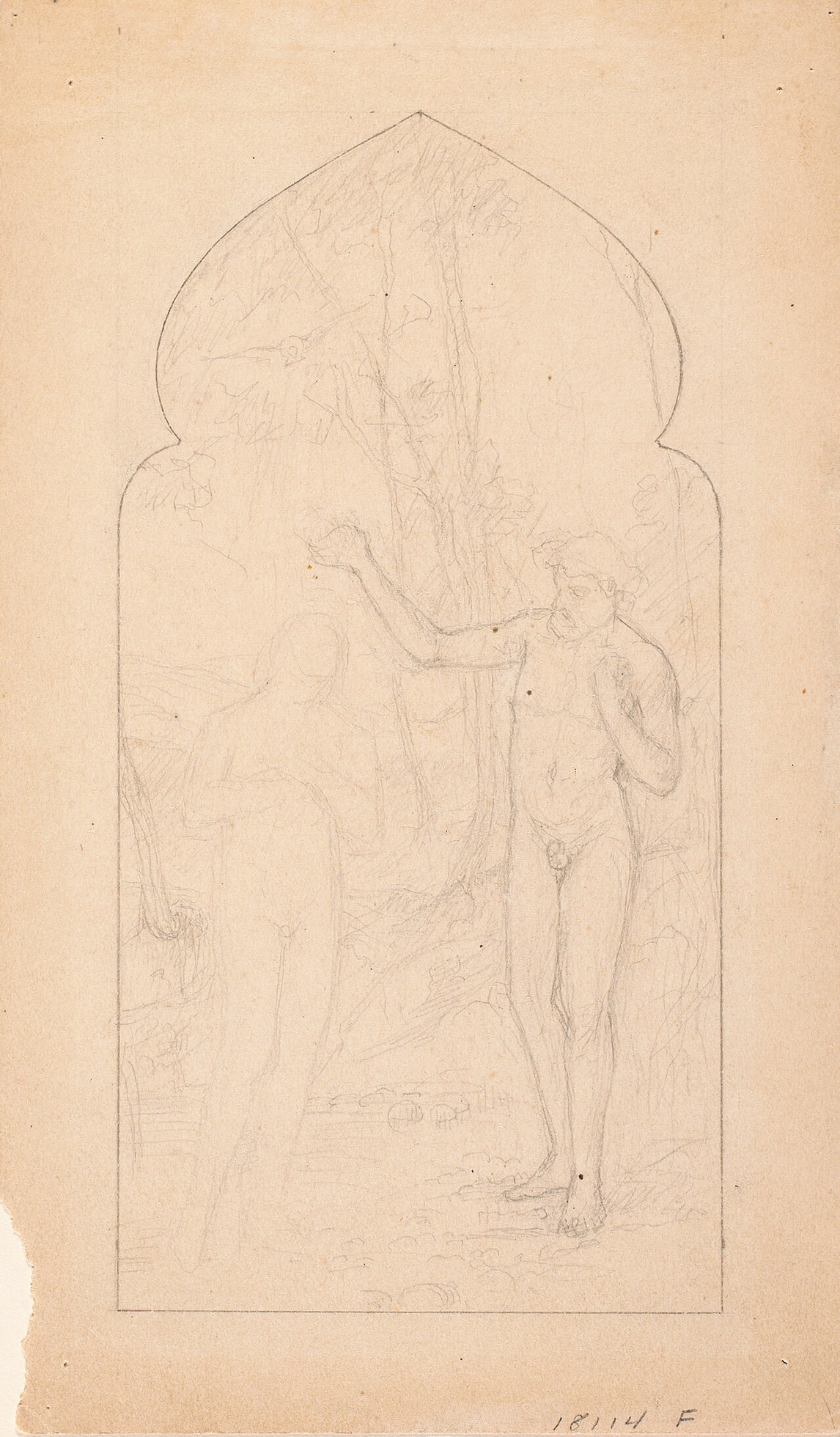

Leduc was acquainted with these new artistic currents, thanks to the periodicals to which he subscribed and to his sojourn in France in 1897. Allusions to the Pre-Raphaelites (for example, Edward Burne-Jones [1833–1898]), to Art Nouveau (in the decor of Saint-Hilaire), and a marked interest in Symbolism can all be found in his paintings. At first, he adopts a principle of Symbolism defined as the meaning attributed to colours and specific subjects. However, his interest did not stop there, and in the tempered spirit of the fin de siècle movement—Leduc never fell into decadentism or art for art’s sake—he rendered an ideal world where meaning lay hidden behind appearances and could be conveyed only by suggestion or metaphor. Form and content were intimately linked, and the work achieved its allusive purpose through the organization of content, colour, and form.

Not many Canadian artists followed this path. Some, such as Cullen and Suzor-Coté, were more drawn to exploring the influences of Impressionism, and others, including Joseph-Charles Franchère (1866–1921), Joseph Saint-Charles (1868–1956), and Edmond-Joseph Massicotte (1875–1929), pursued a more academic style that could be turned to the service of a patriotic or national cause. However, like the Montreal poet Émile Nelligan and Leduc’s friend Guy Delahaye, who were equally devoted to this aesthetic, Leduc would dedicate the rest of his life to his ideal, sustained by his attachment to Saint-Hilaire, which continued to nourish his imagination. He did not render the world in which he lived in a realist or documentary manner, but rather by an artistic practice dedicated to analysis, meditation, and contemplation, which is a unique contribution to Canadian culture.

A Living Legend

Ozias Leduc’s production proceeded along two distinct paths, in two separate fields of art, amounting to more than thirty church and chapel decorations and a small but significant output of easel paintings. Knowledge of his work was and continues to be hampered to an extent by its wide dispersal: to see and appreciate all of his religious work requires travelling to many different places in Quebec, Nova Scotia, and New Hampshire; in addition, many of his church decorations have been destroyed. His easel paintings were for a long time preserved by private collectors and have since been acquired by major Canadian public collections, where they are exhibited regularly.

The artist’s name and work acquired legendary status within his lifetime, due to the aura of mystery created by the rarity and uniqueness of his art. Critics responded to his public exhibitions by emphasizing the originality of his technique, subject matter, and thought. An entire myth grew up around his personality. Writing in L’Opinion publique, Lucien de Riverolles commented: “He was born in a parish where picturesque views abounded, and his love of nature began in his earliest youth. With the aid of no teacher, never having taken a lesson, he became an artist. ‘Art,’ he said, ‘cannot be taught. Nature calls forth art, because it contains within itself both the idea and the mode of its expression.’”

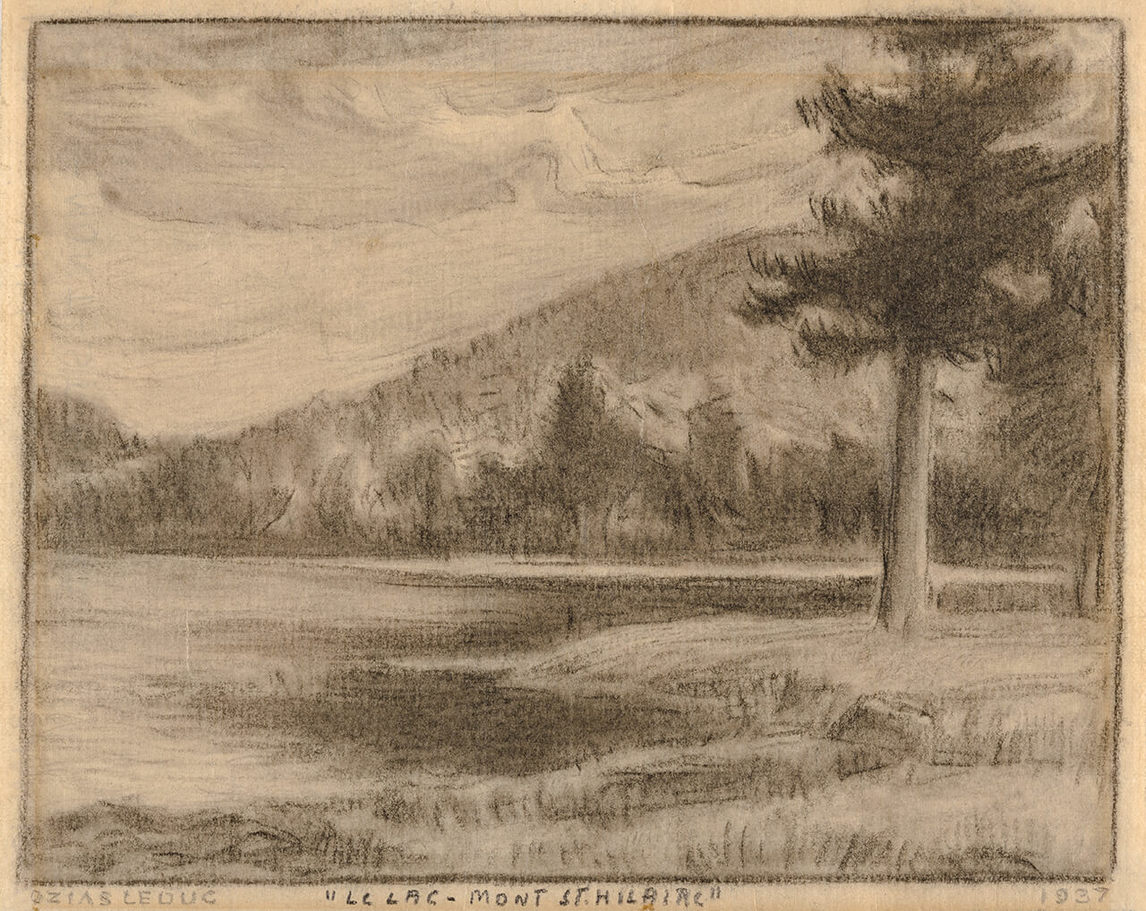

Such statements, no doubt encouraged by Leduc, constituted the basis of a romanticized popular image of the artist that would only increase with time. Leduc himself drew a distinction between how he as an artist self-fashioned and the approaches he made use of in his art. Without acknowledging the instruction and advice he had received from Luigi Capello (1843–1902) and Adolphe Rho (1839–1905) during his time in their studios, Leduc asserted that it was his contact with nature, and nature alone, that informed and cultivated his art. Nature had not only furnished the subjects of his paintings but also the artistic means for achieving their creation. The unique geographical and geological features of his environment had offered figures and forms that in themselves stimulated the work of the artist’s imagination, as seen in Day’s End (Fin de jour), 1913, Gilded Snow (Neige dorée), 1916, or Cloud on a Mountainside (Nuage à flanc de montagne), 1922. Leduc also omitted his study of art history and the dedicated interest he had taken in the works of certain artists who had been a constant source of inspiration.

The fact that Leduc was often away from home for months at a time working on church commissions in various places, together with the relative isolation of his studio at the foot of Mont Saint-Hilaire, gave rise to the myth of the “hermit,” or “sage”—terms often used to describe him in the 1920s, supporting the idea that his was an entirely original art, uncontaminated by any outside influences. Paradoxically, it was in these very years that his studio was most heavily frequented by the Quebec intelligentsia, as artists, intellectuals, and students flocked to meet the artist who lived “in isolation in his remote part of the country.”

Leduc’s art attracted the interest of different groups of admirers at different points in his career. In 1918 it was the young intellectuals associated with the magazine Le Nigog; later, in the 1940s, the Automatistes were frequent visitors to his Saint-Hilaire studio. An interest in his work manifested at the time of his death in 1955 but dimmed in the 1960s and 1970s. In those decades, mentions of his name in print usually identified him only as the teacher of Paul-Émile Borduas, leader of the Automatistes, as if Leduc’s influence on the younger painter had been his principal contribution. (Borduas would go on to exercise a decisive influence on modernism in Quebec, and was at that time the focus of a great deal of critical attention.)

Since 1955 Leduc’s name and his art have continued to hold their unique aura. His easel paintings are rare and jealously guarded by collectors, and very seldom appear on the market. Many of his other works are held by museums across the country and exhibited in their permanent collections. His paintings have been shown successfully at various events, including retrospectives in 1974 and 1996. Unfortunately, many of his church murals have been disfigured by unsuccessful attempts at restoration, in which the images were overpainted rather than cleaned. But it is notable that a younger generation of artists continues to discover Leduc and find inspiration in his work. Sheila Ayearst (b.1951) referenced several of his paintings in her exhibition Still Life at Mercer Union in 1988. More recently, Daniel Olson (b.1955) created a sonic interpretation of Boy with Bread, 1892–99, in his video Love and Reverie, 2001. These artists, like the viewers who experience Leduc’s work, celebrate the slowness and reflectiveness of his art, which measures the beauty of the world.

Posthumous exhibitions of Leduc’s work occurred at the National Gallery of Canada in 1974 and Concordia University in 1978. These exhibitions marked the beginning of academic interest in the artist. Theses and dissertations began to be devoted to specific aspects of his oeuvre, such as the decoration of a certain church or his work in different artistic genres (still life, for example, or portraits). Other works explored his artistic milieu and the critical reception of his work. A major retrospective in 1996 represented a synthesis of the work of the previous twenty years, over which time research had focused on a complete reading of the archives and a systematic study of his entire career.

Yet despite these numerous publications devoted to Leduc’s oeuvre, thought, and personality, much remains to be learned. Many aspects of his career have not been explored. For example, there has been no serious research into his photography, and many of his writings on art are still unexamined and unpublished.

Some of Leduc’s church decorations have not yet been studied, and the task is only growing more complicated, as many of them are in a poor state of conservation. Several of the artist’s most important religious paintings have been destroyed, among them his first such project, the Church of Saint-Michel (Rougemont), and the churches of Notre-Dame-de-Bonsecours (Montreal) and Saint-Edmond (Coaticook); others, including Saint Ninian’s Cathedral (Antigonish), Saint-Enfant-Jésus (Mile End, Montreal), and Saint-Anges (Lachine, Montreal), are badly disfigured by overpainting. Nothing is left of these works but archival documentation. Leduc’s unique and important art deserves closer analysis to increase our understanding of the complex interworkings of its many manifestations. His thought remains current and its significance has much to offer today’s contemporary artists.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements