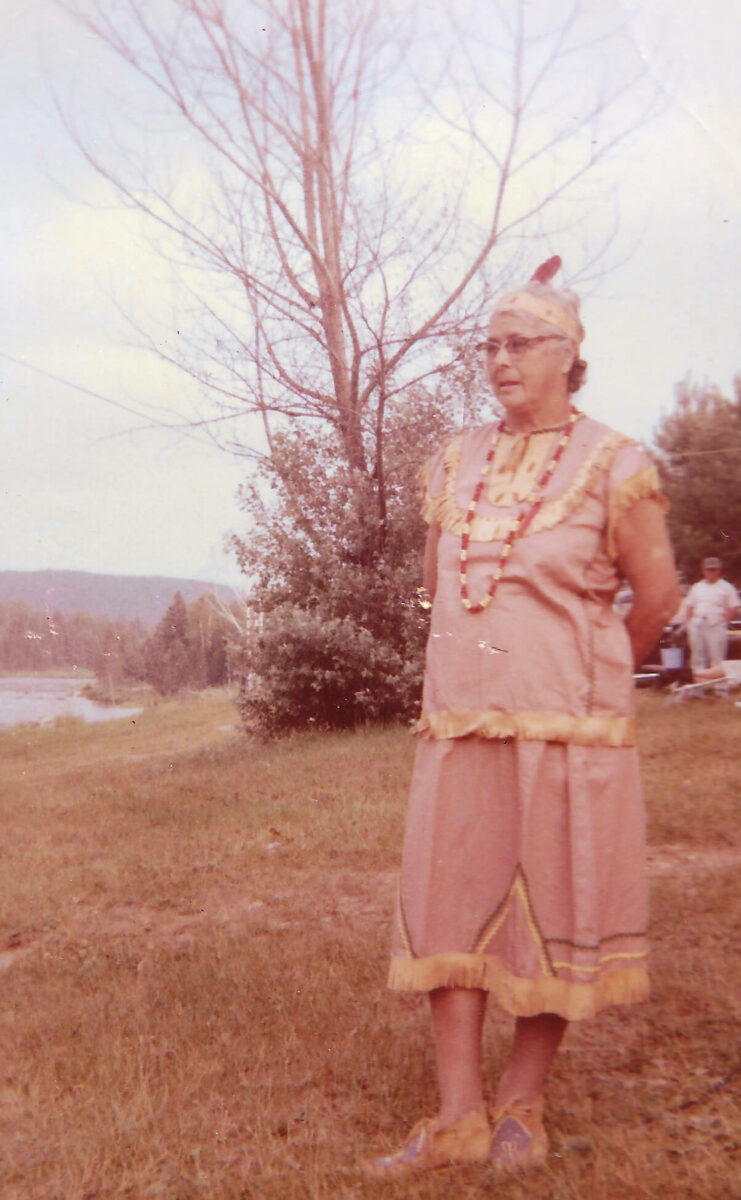

Sarah Lavalley

Sarah Lavalley, Pakigino kabodawayan [buckskin jacket], 1969

Pakigan [buckskin], beads, silk, thread, buttons, 68.6 x 43.4 cm

This buckskin jacket, made from two deer hides and embellished with beadwork on both front and back, is by Anishinābe artist Sarah Lavalley (1895–1991). She learned traditional crafts from her mother, Mary Ann Lamabe, and her mother-in-law, Annie Michell, and became well known for her skills in producing moccasins, mittens, jackets, and other types of hide clothing. She decorated them with beadwork, usually floral and geometric designs, as seen in this jacket. Like other Indigenous artists, including fellow Anishinābe Catherine Makateinini (Michel) (1871–1916) of Kitigan Zibi, or Mary McGregor-Ace (1900–1985), an Odawa of M’Chigeeng First Nation, Lavalley kept alive cultural practices that she passed on within her community.

Sarah Airth or Partridge (both names were used by her parents) was born on the Pikwàkanagàn First Nation on the shores of Golden Lake, Ontario, and grew up speaking only Anishinābe. She learned English in the reserve day school, which she attended until grade eight. She then went to high school in nearby Eganville, but quit soon after because white students made fun of her clothing and called her demeaning names. She spent a few years in domestic service in Eganville and Ottawa, leaving when a member of the family she worked for came down with tuberculosis. Seeking to become a nurse, she attended a Catholic nursing school in New Jersey for nine months before returning to Pikwàkanagàn. In 1916 she married James Lavalley, with whom she raised eight children.

During the 1920s, the family often subsisted on the income generated by her husband and brother-in-law’s hunting and trapping, and both men were subject to harassment and arrest for poaching. Eventually James became a Canadian National Railway trainman, while Sarah’s skills as a midwife and nurse, and her assistance to the local Catholic priests, made the family less dependent on a traditional livelihood. As well, her skills in cooking game led to work in hunting camps, and her abilities as a craftswoman enabled her to develop a market for her skin clothing, which she sold both on the First Nation reservation and at the annual Indian Arts and Crafts display at the Canadian National Exhibition in Toronto in the 1960s and 1970s. She also filled orders for clients in the United States and Europe.

The work of Indigenous artists such as Lavalley and her brother-in-law Matthew Bernard (1876–1972) kept the arts of the Anishinābe alive during a long period of neglect and colonial oppression. She was eventually recognized for her efforts, being named to the Order of Ontario and subsequently to the Order of Canada. She passed away in January 1991.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements