For Ottawa, as elsewhere, there have been many occasions when its citizens have taken significant steps forward in their efforts to build a better city, establishing institutions and organizing associations. As well, there have been many critical events that shaped the city’s art community, some high profile and others that did not seem transformative at the time but were capable of rapidly changing public perceptions and attitudes later. Many forces—political, financial, cultural—are always at play in the arts, and everything from a bazaar to clubs, a national gallery to a local one, a protest to an award have played a part in creating the artistic community in Ottawa today.

August 1846: Pictorial Bazaar

Anishinābe cultural practices, such as storytelling and shamanistic rituals, have been used to pass on Indigenous knowledge for hundreds of years, but the sale or trade of such objects as baskets, clothing, and jewellery are part of the colonial history in the Ottawa area. In 1846, a Pictorial Bazaar took place in Bytown (as Ottawa was then known)—the earliest known public display of artistic products in the region. Such “bazaars” had been a feature of other Canadian cities since the 1830s. In an age when government funding for education, social services, and the poor was almost non-existent, bazaars allowed the public-minded an opportunity to show their charitable side. They also contained the seeds for more artistic endeavours.

The Bytown Gazette advertised the bazaar on August 20, 1846. The admission fees were to be directed to the chapel funds of the British Wesleyan Society to assist in missionary work in Canada and overseas. Almost 200 watercolour drawings were offered for sale, including flower paintings and views of Bytown, the Chaudière Falls and Bridge, New Edinburgh, and other locations. Also on offer were decorated boxes, albums, fire screens, and needlework.

John Burrows (1789–1848), who organized the event, had arrived in Canada in 1815 and settled in Nepean Township (as Bytown was then known). He became a surveyor, and his artistic talent was immediately appreciated by government officials. As a clerk of works on the Rideau Canal in 1827, he executed many watercolours as part of his job, and he created several views depicting the area, such as Bytown Bridges, c.1835. Burrows settled in Bytown, became a town councillor, and acquired considerable property. His works may have been for sale at the bazaar, but the majority of products were probably crafted by students.

For young women of a certain economic milieu, social mores limited prospects for employment. Drawing was one of the pastimes they could pursue. Mary-Anne Pinhey (1821–1896), for example, recorded her family’s property on the Ottawa River in 1837. She later published a lithograph depicting the estate—View of Horace-ville [sic] on the Ottawa River, Upper Canada, was printed in London, England, around 1839. Little is known about the teachers or students from private drawing academies, and few works from this period survive.

Burrows’s death in July 1848, coupled with the passing of painter and drawing master Robert Auchmuty Sproule (1799–1845) in late 1845, deprived the community of two important artistic leaders who could have rapidly built an appreciation of the arts in a growing community.

1847–1853: Bytown Mechanics’ Institute

For many nineteenth-century Canadian cities, the establishment of a Mechanics’ Institute was a demonstrable mark of progress in terms of education. Providing access to every segment of society, both men and women, Mechanics’ Institutes featured lending libraries containing inspirational and vocational reading matter for tradesmen and workers, as well as newspapers and popular fiction. They also offered lecture courses and laboratories, and sometimes they contained a museum. There was a Mechanics’ Institute in Montreal in 1828, York (Toronto) in 1830, and Halifax in 1831.

The original Bytown Mechanics’ Institute was founded in 1847 by a group of businessmen, professionals, and clergymen, but it closed only two years later. This has been attributed to high subscription fees, poor fundraising efforts, the existence of a rival organization, and the withdrawal of French Canadians from the Institute in 1849. The Bytown Mechanics’ Institute and Athenaeum (BMIA) was re-established in January 1853, seeking to pursue scientific, literary, and artistic learning. The new organization held an art exhibition in August of that year, which included works by William S. Hunter Sr. (active 1836–1853) and F.B. Hely (active 1853–1867). It also began to accept donations, including ornithological specimens and, significantly, Indigenous artifacts. Its library included dozens of rare illustrated books, such as Sir William Jackson Hooker’s book Victoria Regia: or, Illustrations of the Royal Water-Lily (1851) and Illustrations of the American Ornithology of Alexander Wilson and Charles Lucian Bonaparte (1835).

The BMIA evolved over the next several years, becoming the Ottawa Literary and Scientific Society in 1869. This organization disbanded in 1907, and historian John H. Taylor notes that much of its role—especially lectures and intellectual discourse—was subsequently assumed by the Ottawa Arts and Letters Club (1916), which in turn would be dissolved in 1937.

In its heyday, the Mechanics’ Institute reflected the stratification of Ottawa’s social and cultural milieu, being overwhelmingly Anglo-Protestant in its membership and orientation. French Canadian and Catholic interests were served by the bilingual College of Bytown (now the University of Ottawa) and the Institut canadien-français d’Ottawa. It was only in the later twentieth century that other ethnic and cultural organizations, such as the Goethe Institute, would appear. The role of the original Mechanics’ Institute and its successors merits recognition, as for several decades it was the only public library in the city. Its sponsorship of art exhibitions, music, debates, and lectures provided an intellectual stimulus within a rising middle class in a relatively isolated community. Its collections, including Indigenous artifacts, would one day be incorporated into municipal and national museums.

1879: Fine Arts Association of Ottawa

Until 1879, Ottawa had no artistic organization to compare with the Art Association of Montreal, founded in 1860, or Toronto’s Ontario Society of Artists, established in 1872. Spurred on by a call to action from the Governor General, the Marquis of Lorne, several prominent citizens, including Supreme Court judge Sir William Johnstone Ritchie, lumber merchant Allan Gilmour, architect John William Hurrell Watts (1850–1917), photographer William J. Topley (1845–1930), engineer Sandford Fleming, public servant Edmund A. Meredith, and lawyer Mr. Leggo, met in May 1879 to discuss the foundation of an art association in Ottawa.

They formed a society, and at a public meeting at City Hall on July 8, expressed their aims as “encouragement of knowledge and love of the fine arts, and their general advancement throughout the Dominion. As means of obtaining this object, it is proposed to open a School of Art and Design in Ottawa; to establish an Art Union, and hold annual exhibitions in that City, and to use the influence of the association in promoting the creation of a National Gallery at the seat of government.” These ambitious aims perfectly demonstrated the conflicting ethos among the leading citizens of Ottawa, torn between the promotion of national institutions and local ones. Their twofold efforts rapidly succeeded: the Canadian Academy of Arts (after 1882 the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts [RCA]) and the National Gallery were founded in March 1880, while the Ottawa Art School opened the following month.

The early years of the Fine Arts Association of Ottawa were highly successful. Support from the Marquis of Lorne and his wife, Princess Louise, the RCA, and the local community enabled it to purchase quarters on Sparks Street in downtown Ottawa in 1883, the same year it took the name the Art Association of Ottawa.

In exchange for modest fees and with no enrolment restrictions, the school educated aspiring painters, sculptors, architects, and practitioners in applied arts. Like the Ontario School of Art (now the OCAD University) in Toronto, its training was intended to “help to mould and elevate the general feeling of the public in all that pertains to art… the manufacturing skill and capacity of the country would be enormously increased if every young mechanic could be induced to attend [classes].”

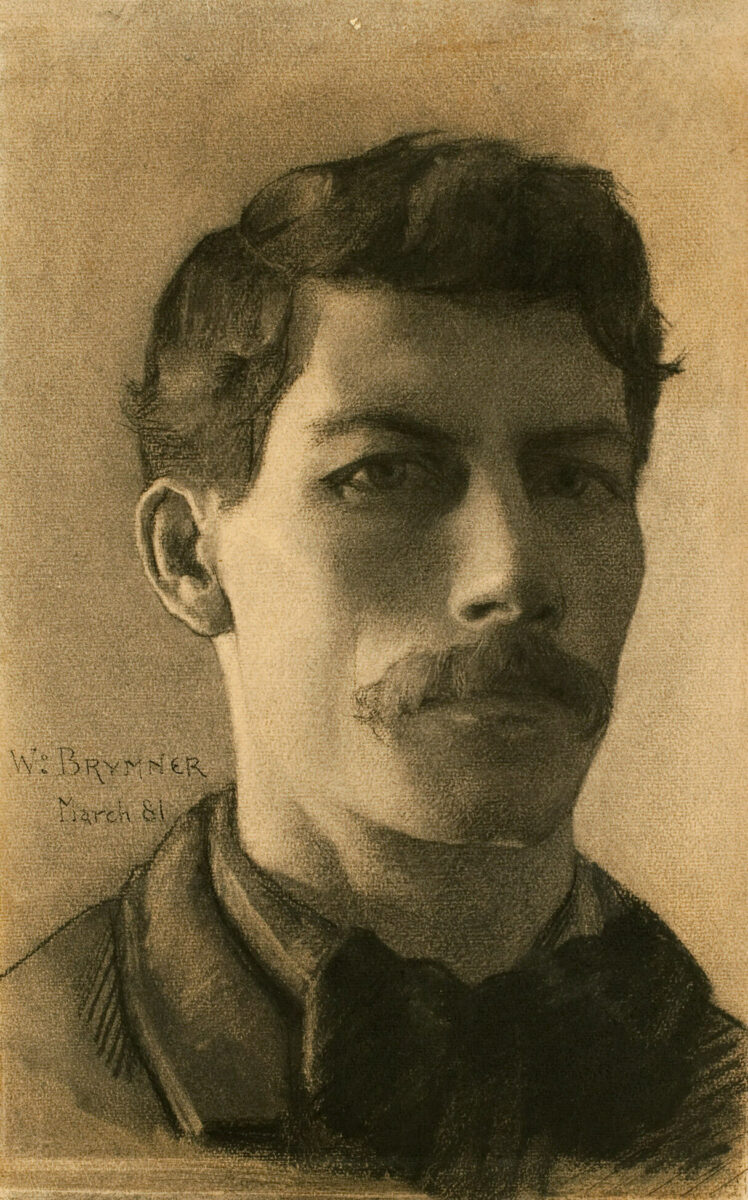

The program prospered under the direction of its first headmaster, William Brymner (1855–1925), assisted by Mrs. Cowper Cox and Frances Richards. After Brymner returned to Paris in 1883, his successor was American-born and Paris-trained Charles E. Moss (1860–1901), under whose tenure the teaching staff grew from four to nine. In 1886–87, enrolment peaked at 184 students with the introduction of courses in freehand drawing, clay modelling, and art needlework.

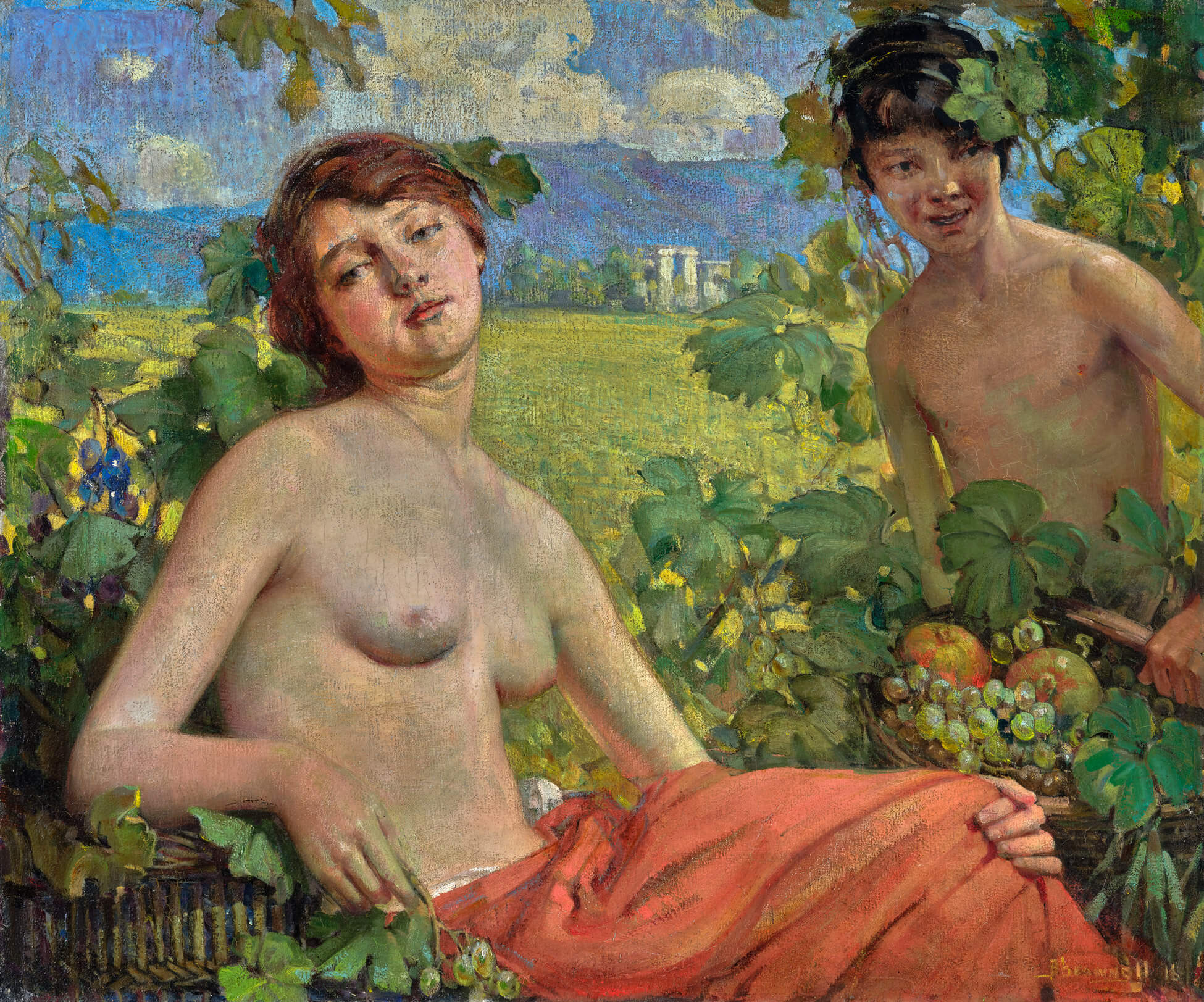

In 1887, Franklin Brownell (1857–1946) became the headmaster until 1900, when the school closed due to financial difficulties. In its first twenty years of existence, the school had launched the careers of such artists as Robert Weir Crouch (1865–1943) and Ernest Fosbery (1874–1960), architects Moses Edey (1845–1919), Werner E. Noffke (1878–1964), and J. Albert Ewart (1872–1964), and photographer May Ballantyne (1864–1929), among others.

1880: National Gallery of Canada

Perhaps the most influential single institution in the history of the fine arts in Ottawa is the National Gallery of Canada, the idea for which originated with the Governor General, the Marquis of Lorne, and his wife, Princess Louise. He first broached the subject in a private meeting with the vice-president of the Ontario Society of Artists (OSA), Lucius Richard O’Brien (1832–1899), in Ottawa in February 1879, and he then stated it publicly at the dedication of a new building for the Art Association of Montreal (AAM) on May 26, 1879. Two days later, several prominent Ottawa citizens held a meeting to organize the Art Association of Canada, and to promote a “National Gallery” in order to encourage “knowledge and love of the fine arts, and their general advancement throughout the Dominion.”

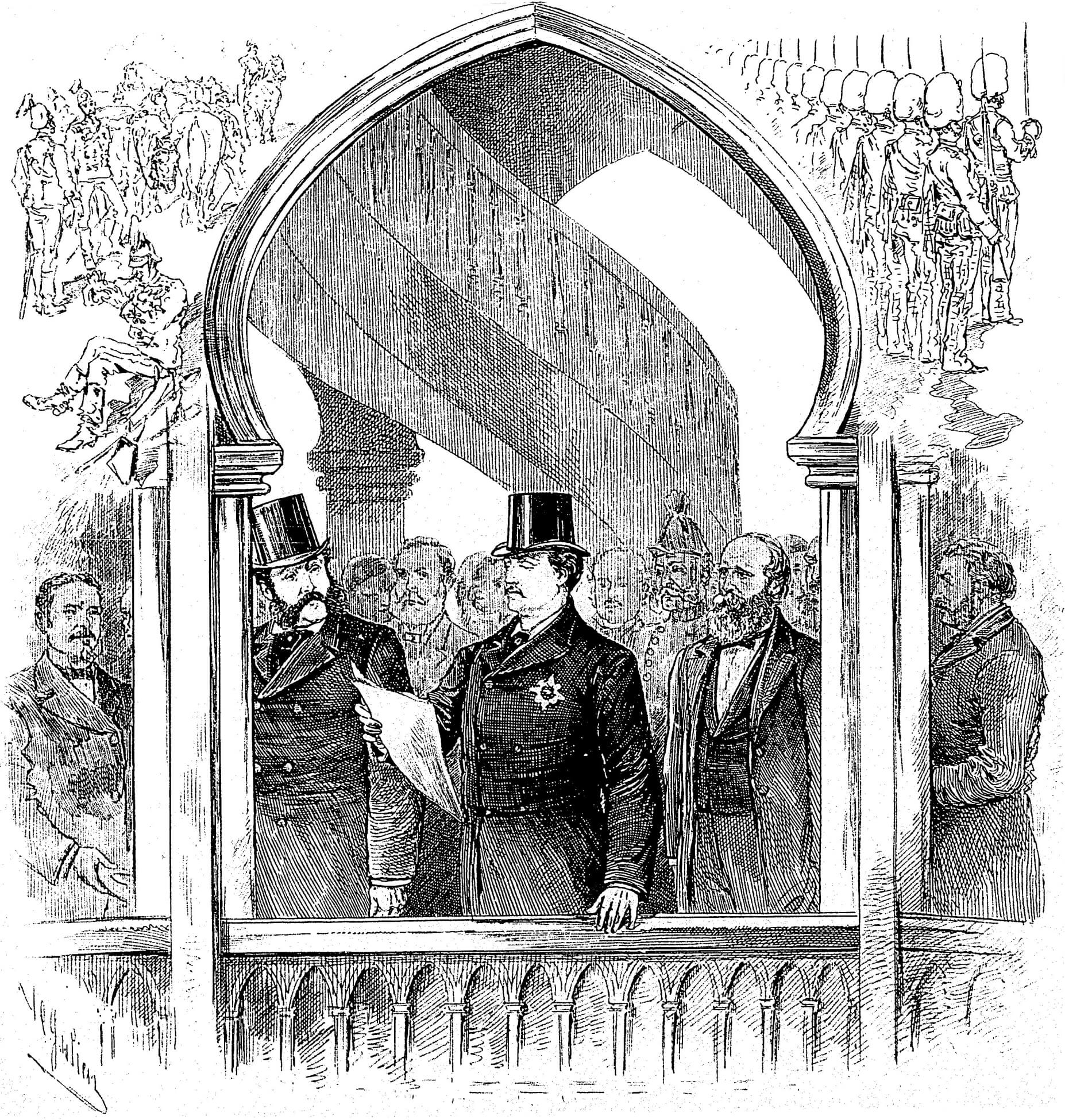

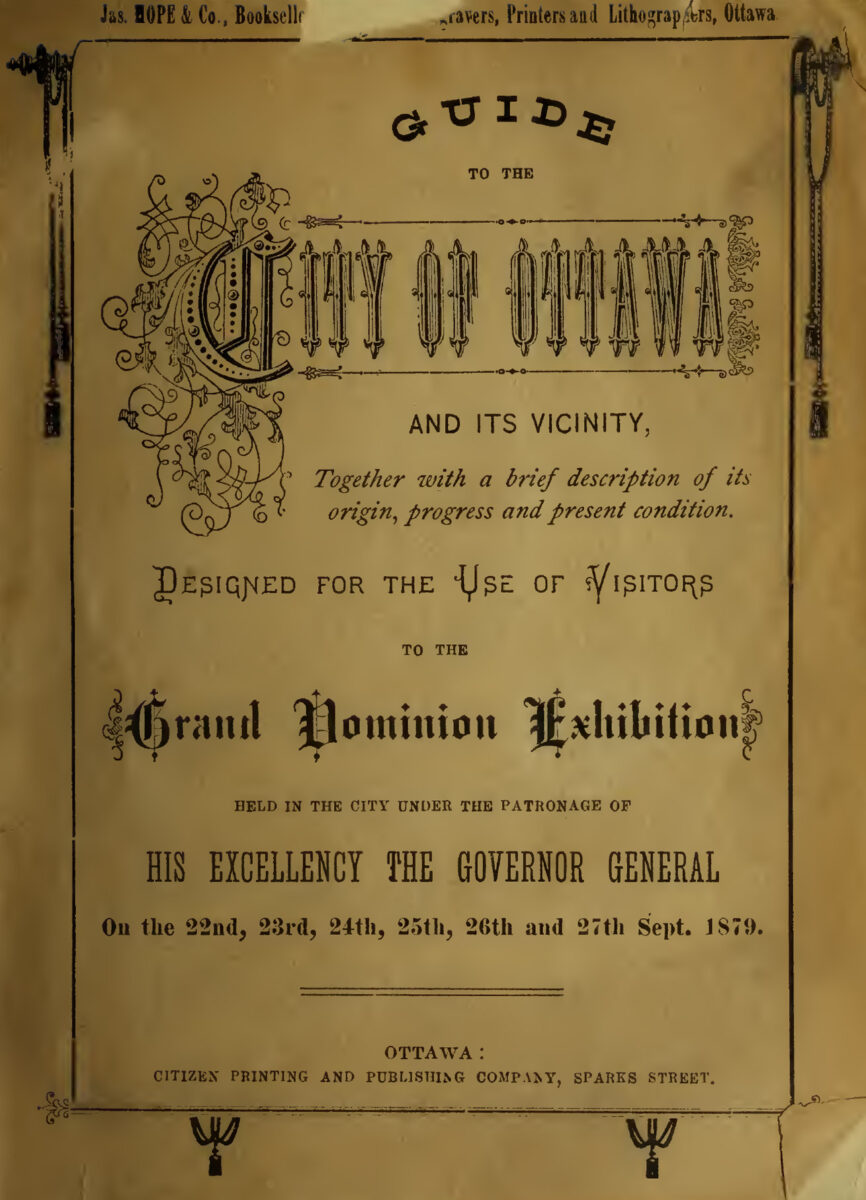

The Marquis of Lorne sent a letter to O’Brien on June 8, 1879, outlining the proposal for a Dominion art association, including an appointed membership, annual exhibitions of art from across Canada to be held in centres outside of Toronto and Montreal, and a permanent national gallery. Lorne also stated that cities that failed to develop local art schools and institutions would not be allowed to host shows. Working with both the OSA and the AAM, Lorne presided over the Grand Dominion Exhibition in Ottawa in September 1879, which included the first presentation of art from throughout the country in one location.

Within a few months, the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts (RCA), with O’Brien as its first president, and twenty-one selected academicians (although only one woman), had become a reality. The first exhibition opened in Ottawa on March 6, 1880, in a building made available by the federal government. The RCA became responsible for the National Gallery and for organizing annual shows. When members were appointed academicians, they were required to submit a work of art or diploma piece to help form the national collection, which was displayed in a space in the original Supreme Court building from 1882 to 1888. The first curator was public works architect John William Hurrell Watts. In 1888, the National Gallery moved to the second floor of Victoria Hall, where it remained until 1911.

Watts was succeeded by another government architect, Lawrence Fennings Taylor (1862–1947), in 1897. The collection grew slowly as diploma pieces were deposited, and gifts, such as a group of plaster sculptures for educational purposes presented by Princess Louise in 1890, were added. Acquisition funding was almost non-existent, and few Ottawa artists, with the exception of Franklin Brownell, were represented in the collection. In its first two decades, the gallery attracted fewer visitors than the neighbouring fisheries exhibit.

In 1910, Toronto businessman Byron Edmund Walker became chair of the government’s Arts Advisory Council. He arranged the move of the National Gallery to a wing of the new Victoria Memorial Museum and hired its first independent curator, Eric Brown, who eventually became the director; as well, a budget for acquisitions was established. Brown and his wife, Maud, quickly became part of the Ottawa establishment, and they ensured that the city’s artists were represented in the gallery, purchasing such works as Brownell’s Golden Age, 1916, the year it was painted, and Ernest Fosbery’s mezzotint The Storm, c.1918, two years later. In the 1930s, an annual International Salon of Photography was held at the National Gallery due to Brown’s support for that art form.

The effects of the Great Depression, Brown’s death in 1939, and the onset of the Second World War had significant impacts on gallery activities. New director Harry McCurry began a wartime program, commissioning artists to serve overseas with Canadian forces and record military efforts—participants Tom Wood (1913–1997), Harold Beament (1898–1984), Robert Hyndman (1915–2009), and Charles Anthony Law (1916–1996) were from Ottawa. McCurry also launched a Canadian art reproduction program in conjunction with the Sampson-Matthews company in 1942.

At the end of the war, the gallery resumed its acquisitions. Vincent Massey made important donations, and significant works were purchased from the Edwards family, whose success in the lumber industry had enabled them to form a collection of modern European art. Exhibition spaces remained wholly inadequate, and after a failed effort to construct a new building, the gallery moved to a repurposed office building on Elgin Street. This move enabled the National Museum of Canada (now the Canadian Museum of History) to increase its space devoted to Indigenous art and culture, including a large birchbark canoe newly built by Anishinābe craftsman Matthew Bernard (1876–1972) of Pikwàkanagàn.

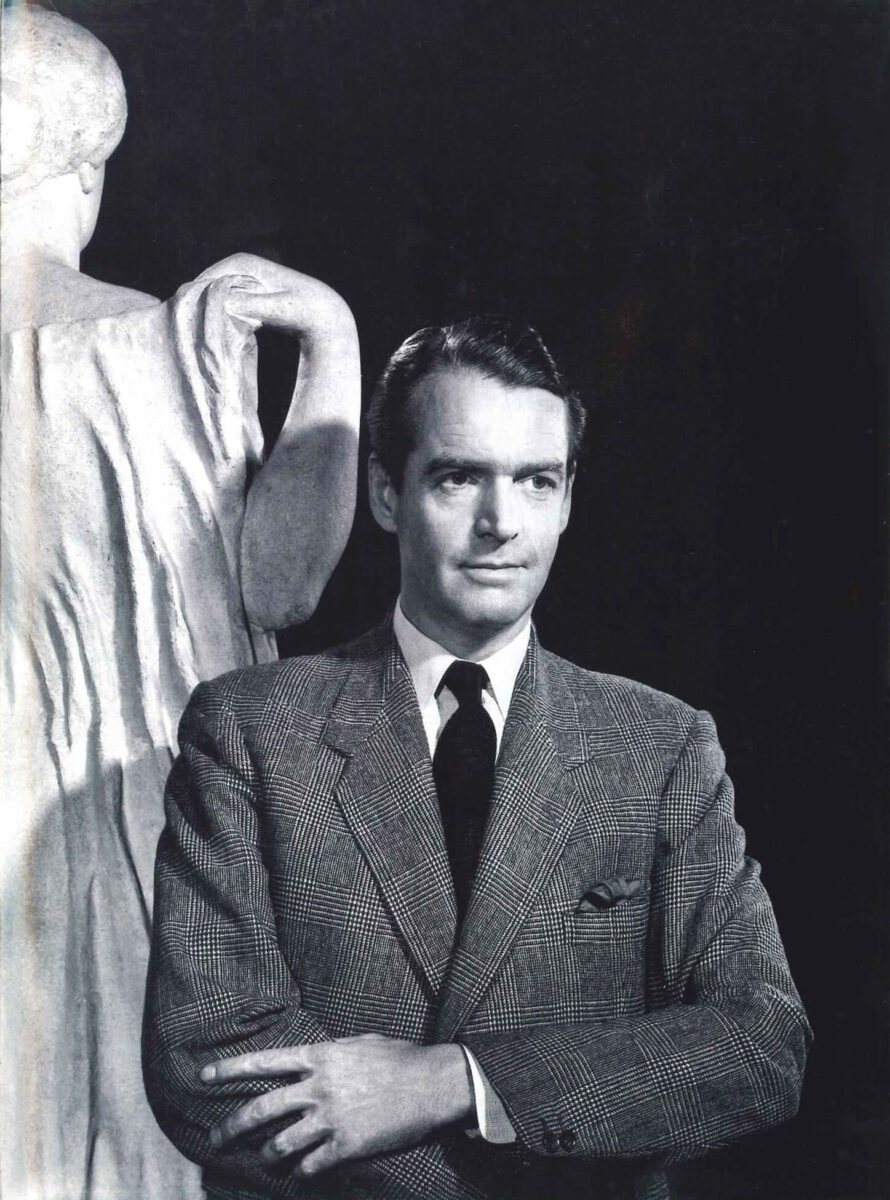

Alan Jarvis succeeded McCurry as director in 1955. He promised to promote Canadian art and design, but his tenure was cut short by disputes with the Conservative government and health issues. Artist Charles Comfort (1900–1994) became director in 1959, disappointing many because of his conservativism and lethargic approach. He was succeeded by the dynamic Jean Sutherland Boggs seven years later.

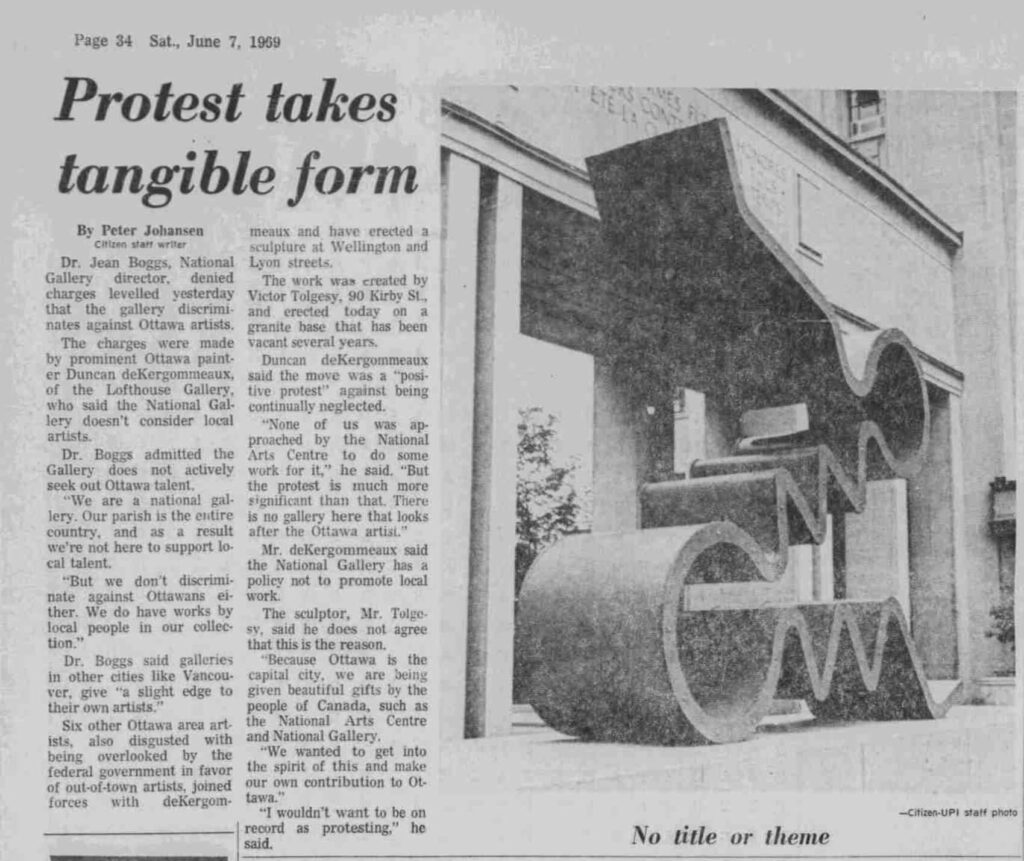

In the 1960s, Ottawa artists were so dismayed by the gallery’s perceived lack of interest in their community that they held a symbolic protest in June 1969. Boggs responded, “We are a national gallery. Our parish is the entire country… we’re not here to support local talent. But we don’t discriminate against Ottawans either.” The realization that the gallery was primarily a national institution finally spurred the local arts community into action. By the mid-1970s, the push for a municipal art gallery was well under way, even as the National Gallery itself was planning to move. Its new building, designed by Moshe Sadfie (b.1938), opened in May 1988.

The relationship between the National Gallery of Canada and the Ottawa community continued to be ambivalent. Under the directorship of Shirley Thomson, controversy arose in 1995 over the cancellation of a display of work by Ottawa-based artist Dennis Tourbin (1946–1998). Then, a 1998 Ottawa Art Gallery exhibition on Brownell brought to light the fact that none of his works were on display in the National Gallery itself.

While the National Gallery owns pieces by many Ottawa artists, they are still under-represented in both permanent and temporary exhibitions. The creation of the Ottawa Art Gallery and the Carleton University Art Gallery, as well as many artist-run spaces, has enabled Ottawa artists to become more visible, but the difficulties of establishing historical figures within a national canon remain.

1894: Ottawa Camera Club

Popular interest in photography exploded in Canada in the late nineteenth century after the introduction of dry plate gelatin photography in the 1870s and the Kodak camera in 1888. The Ottawa Camera Club first met in December 1894; membership was a very affordable $1.00 per year, and the nearly one hundred members who joined included both men and women. Like the Literary and Historical Society and the Ottawa Field-Naturalists’ Club, the club attracted a mixture of public servants and professionals interested in exploring cultural life. The desire to engage in outdoor activities, including excursions to the Gatineau Hills and Britannia Park, also animated such organizations.

Participants were mostly enthusiastic amateurs, with a sprinkling of artists, scientists, and professional photographers. Original members included William Ide (1872–1953), a senior public servant and private secretary to several Cabinet ministers who became one of the most distinguished amateur photographers in Canada, and Ottawa manufacturer James Ballantyne, whose daughter May held a senior position with the club. Being involved was an opportunity to learn about photographic techniques through lectures such as “Summer Photography,” “Retouching the Negative,” “Platinotype Printing,” and “Composition.”

The Ottawa Camera Club fostered significant changes on the cultural scene over the next several decades. Twelve members, including Charles E. Saunders (1867–1937), Madge Macbeth, William J. Topley, John S. Plaskett (1865–1941), and Charles Macnamara (1870–1944), broke off from the club in 1904 in order to bring Ottawa closer to contemporary developments in art. Plaskett’s experiments in colour photography, and Ide’s work with different media, such as platinum printing, and his investigations of pictorialism (evident even in early works like The Watering Place, 1895–96), as well as similar stylistic explorations by Frank Shutt (1859–1940), all demonstrated photography’s possibilities as an artistic medium. Biannual exhibitions or salons of local work attracted other Canadian and international photographers. The Photographic Art Club was reconstituted as the Camera Club of Ottawa in 1922.

While older members continued to play important roles, younger photographers, including Clifford M. Johnston (1896–1951) and Harold F. Kells (1904–1986), led the way in advancing the cause of artistic photography in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s—Johnston, for instance, is recognized for experimental compositions like The Toilers, after Millet, prior to 1948. Both men exhibited widely in salons in Canada, the United States, Europe, and elsewhere. Johan Helders (1888–1956), born in the Netherlands but living in Ottawa from 1926 to 1939, also had an international reputation. Along with Kells and Johnston, he persuaded Eric Brown to organize the first Canadian International Salon of Photographic Art at the National Gallery in 1934. This groundbreaking event featured the work of Canadian photographers alongside images by famous pictorialists from around the world, with more than 200 pieces exhibited in Ottawa, followed by a highly successful coast-to-coast tour. The success prompted the gallery to make it an annual event, but with the onset of the Second World War, sponsorship was withdrawn in 1940, and an effort to revive the salon in 1946 did not succeed.

The Camera Club of Ottawa, however, still exists, and the impact of this organization in fostering public interest in photography helped create an appetite and a market for it that remains to this day. The National Gallery established a photography curator position in 1967. The Still Photography Division of the National Film Board has for several decades exhibited photographic work from throughout Canada in downtown Ottawa. As well, the visual arts department at the University of Ottawa, from the outset, has had a strong photographic component led by internationally recognized instructors. Finally, Ottawa boasts the School of the Photographic Arts (SPAO), established in 2005 and led by noted local practitioners, among them Whitney Lewis-Smith and Olivia Johnston.

1898: The Ottawa Branch of the Women’s Art Association

The place of women in Canadian art history has only been seriously addressed in the past four decades, but women have always been active as artists, whether pursuing traditional crafts or working as painters and sculptors. History has traditionally celebrated patriarchy, and women artists were for centuries denied access to academies and life drawing classes. All but a few were excluded from the most respected artistic circles, though it should be noted that “Ladies Work” and traditional Indigenous crafts formed part of provincial and international exhibitions, such as the Colonial and Indian Exhibition held in London, England, in 1886. In Canada, this discrimination began to be addressed to some degree with the foundation in 1887 of the Women’s Art Association of Canada (WAAC), which initially provided opportunities for middle- and upper-class women.

The WAAC was begun by a group of artists led by Mary Ella Dignam (née Williams) (1857–1938), who had studied with Paul Peel (1860–1892), as well as in New York and Paris. Informal in its early years, the WAAC was incorporated in 1892 and patronized by Lady Aberdeen, the wife of the Governor General. It encouraged women to work together to paint, draw, and sketch from still life and living models. In 1893, the WAAC extended its mandate to include “handicrafters,” recognizing an area of artistic endeavour where women from more modest economic backgrounds could participate and share their knowledge of traditional crafts.

The Ottawa branch was founded in 1898, with its honorary president being Lady Minto, wife of the new Governor General. It held weekly “art conversations” and annual exhibitions of its students’ work, and it sponsored lectures on the fine arts, including one given by Dignam herself in 1902. In 1907, Franklin Brownell began teaching art classes under the auspices of the WAAC at his studio on Sparks Street. The organization continued to receive support from wives of later Governor Generals, including Evelyn Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire, whose husband was Governor General from 1916 to 1921. Today, the Ottawa WAAC’s activities, membership, and operations remain relatively obscure, although the organization’s archives hold valuable information.

WAAC sponsored a major exhibition in 1921, reviewed by Madge Macbeth in Saturday Night: “The exhibition held… last week in the Chateau Laurier, was not only a notable success but it was a revelation… the first of its kind ever attempted in the Capital…. Its object was to bring the Ottawa artists together, and… [in] providing a ’gallery’—temporary though it was—in which their creations could be shown.” Exhibition organizers included Florence McGillivray (1864–1938), whose own work was featured alongside that of Brownell, Ernest Fosbery, Marie-Marguerite Fréchette (1878–1964), Jules Henri Chaume, Hamilton MacCarthy (1846–1939), and many other artists practising in the capital. A second show took place in 1922, but the Ottawa branch of the WAAC ceased operations in 1923. For three decades it had kept the spirit of art alive in the city and provided a training ground for women, many of whom became full-time artists and art teachers.

1924: Ottawa Artists at Hart House and at the British Empire Exhibition

Sometimes a key moment in artistic life provides the impetus for a complete change in public attitudes. The initial exhibition of the Group of Seven in Toronto in May 1920 is one such example. Inspired by the idea that a distinct Canadian art could exist through direct contact with nature, their work is now considered to be the first major national art movement, and they dominated Canadian art for decades. A similar key show for Ottawa artists failed to ignite public acclaim and, consequently, has been largely ignored. But the Ottawa Group show, held at Hart House at the University of Toronto in 1924, resulted in the selection of a number of their works for the British Empire Exhibition in Wembley, England, and launched the careers of several artists, demonstrating that they too could play an important part in the national scene.

In November 1921, the Studio Club in Ottawa was formed, counting among its members Graham Norwell (1901–1967) and Frank Hennessey (1894–1941). The club’s application for a Royal Canadian Academy Life Study subsidy showed their desire to be recognized for their commitment to art. More needs to be learned about the club’s activities, but the Ottawa Group exhibition at Hart House included both Hennessey and Norwell, as well as Harold Beament, Florence McGillivray, Paul Alfred (1892–1959), and David Milne (1882–1953). Like Montreal’s Beaver Hall Group, the Ottawa Group wanted “to keep alive a healthy interest in art, modern Canadian art in particular.”

The selection process for the Canadian section in Wembley highlighted the debate between traditionalists and modernists. As Douglas Ord has noted, Eric Brown “skilfully organized the juries that chose the paintings, against the opposition of more traditional landscape and portrait painters… wrote the catalogue essays and… arranged the rooms [in Wembley] to keep the hostile sides apart….” The jury included Franklin Brownell, who was seen as a link between younger artists and the older, more conservative establishment. Works by the Group of Seven were well received by the British public and critics alike, but there was little commentary about other pieces. Ottawa was well represented—works by Hennessey, Norwell, Alfred, Beament, McGillivray, Milne, and Kathleen Moir Morris (1893–1986) were on display, including Milne’s Across the Lake I, 1921, and Hennessey’s Wolf Crossing a Lake, 1923.

The Ottawa Group did not last. Beament and Norwell soon left for Europe, and Milne returned to upper New York State. The remaining artists carried on, individually or in conjunction with the activities of the Art Association of Ottawa. Beament and Hennessey would go on to have distinguished careers as artists, although the latter’s tragic death in 1941 cut short what might have been a more significant contribution.

1939: The National Film Board of Canada

One of the most influential cultural institutions ever created by the federal government was the National Film Board of Canada (NFB), envisioned in the midst of the Great Depression, but only brought into existence by the exigencies of the Second World War. It would become a central player in shaping Canada’s self-image and international reputation.

The NFB’s predecessor was the Canadian Government Motion Picture Bureau (CGMPB), founded as the Exhibits and Publicity Bureau in 1917 to document and promote Canada, and plan its participation in international fairs. By 1938 the CGMPB was in disarray, and the government commissioned British filmmaker John Grierson (1898–1972) to assess its future. His report resulted in an act of Parliament establishing the National Film Board in May 1939, with a renewed mission to promote Canada abroad and foster national unity at home.

When war was declared in September 1939, the NFB still lacked a commissioner. Grierson took the job and presided over an increasingly powerful organization, which merged with the CGMPB in 1941. That same year, a Still Photography Division was created, and in 1943 the NFB became responsible for the Wartime Information Board (WIB).

The NFB coordinated the government’s public information activities and the release of war news. Several artists, animators, photographers, and filmmakers were hired and came to Ottawa, contributing both to the war effort and the local artistic milieu. Scottish-born Norman McLaren (1914–1987) arrived in 1941, and he in turn hired filmmakers René Jodoin (1920–2015), Grant Munro (1923–2017), and Evelyn Lambart (1914–1999). Albert Cloutier (1902–1965) came from Montreal to become art director of the WIB, while Ralph Foster headed the Graphic Arts Division. Other artists, including Harry Mayerovitch (1910–2004), Laurence Hyde (1914–1987), Alma Duncan (1917–2004), and Hubert Rogers (1898–1982), also moved to the city. Hyde would become vice-president of the Ottawa branch of the Federation of Canadian Artists in 1945. Cloutier and Duncan both left the NFB in the postwar period, but they stayed in Ottawa, the latter turning her talent to filmmaking in the early 1950s.

The NFB remained an important presence in Ottawa until it moved to Montreal in 1956, making that city a hub of Canadian filmmaking. The Still Photography Division was in Ottawa until the 1980s under the direction of Lorraine Monk (1922–2020), and it eventually became the core of the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography.

1962: Blue Barn Gallery

In the 1960s, Blue Barn Gallery was Ottawa’s major contemporary art space. In conjunction with Toronto and Montreal galleries, it hosted exhibitions by many Canadian artists, such as Victor Tolgesy (1928–1980), Gerald Trottier (1925–2004), James Boyd (1928–2002), David Partridge (1919–2006), Norman Takeuchi (b.1937), Georges de Niverville (1928–1984), Harold Town (1924–1990), and Toni Onley (1928–2004), among others, often providing them with their first national exposure. Blue Barn also placed their work before Ottawa collectors.

Duncan de Kergommeaux (b.1927) was initially responsible for Blue Barn’s artistic program. In 1960 he had been recruited by David Torontow (whose parents were well-known Ottawa art collectors), who urged him to move back to Ottawa, where he had lived in the mid-1950s, to help run the Little Blue Barn furniture store. De Kergommeaux accepted, hoping to work part-time while devoting the rest of his week to art. The store, which sold modern Danish furniture, was very successful, and it moved to a custom-designed building in the Ottawa suburb of Bells Corners. The new premises included a separate space for Blue Barn Gallery, which they hoped, in de Kergommeaux’s words, would “provide a community service, help our friends, and perhaps attract some customers.”

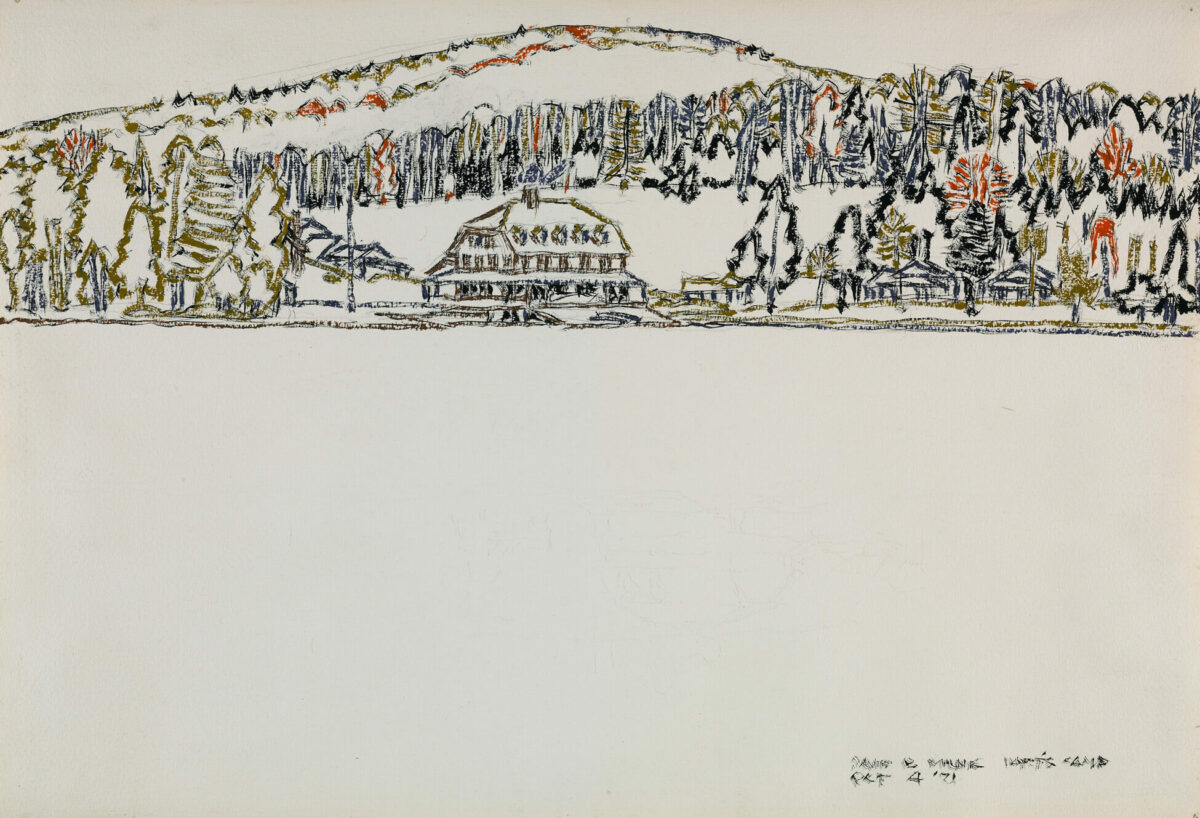

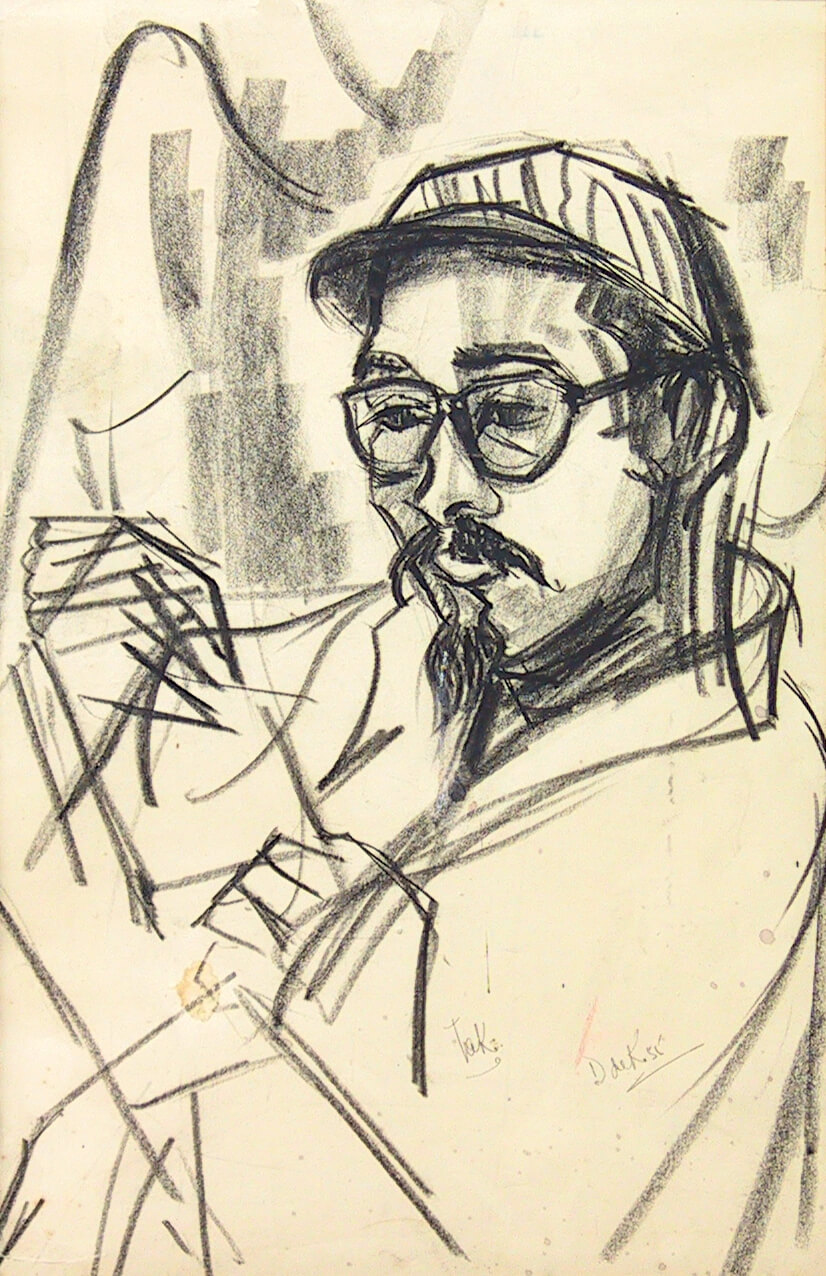

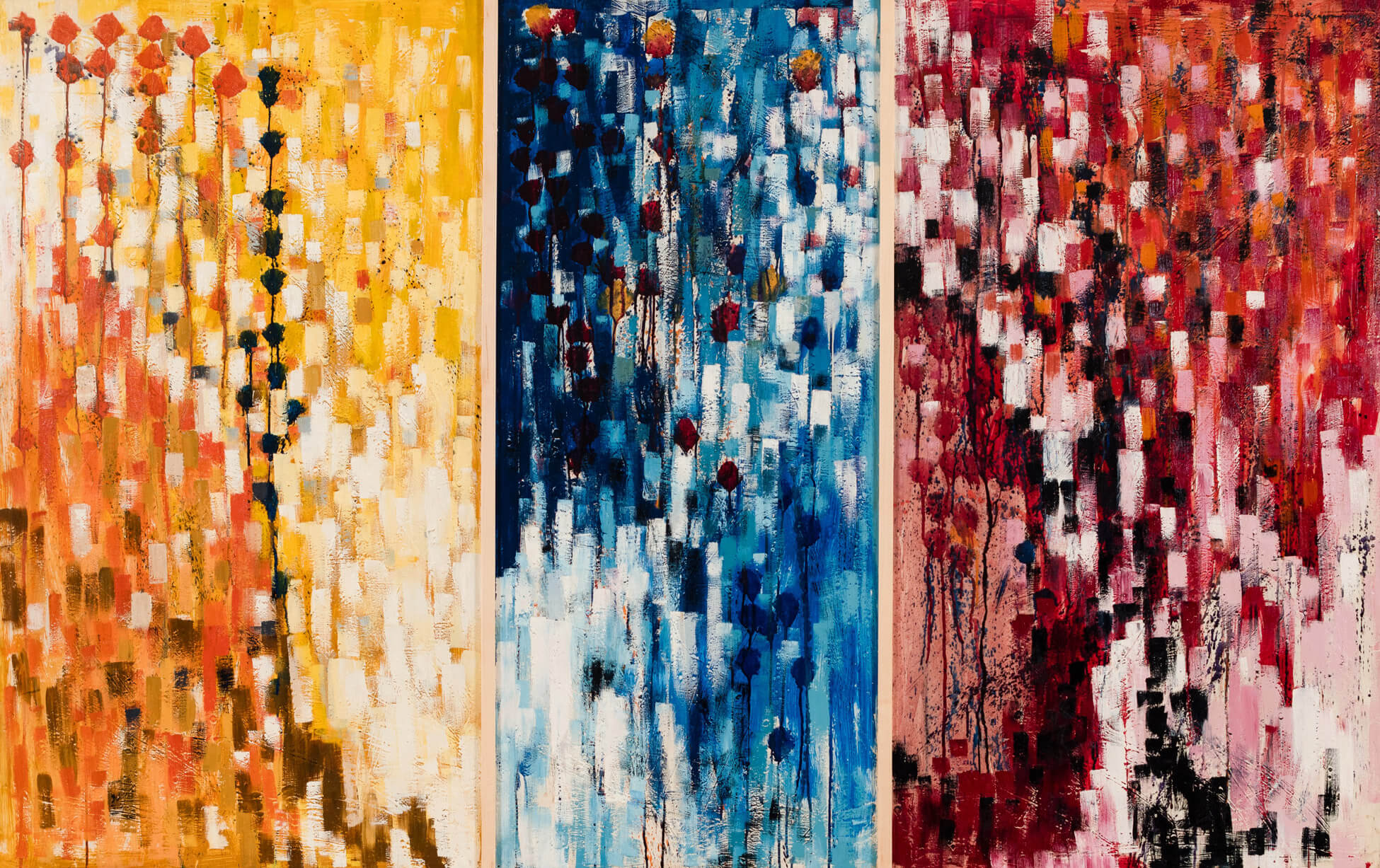

For most of the 1960s, de Kergommeaux was not only a critically acclaimed painter—Yellow, Blue, Red, 1956, is one of his early works—but he was also one of the leaders of Ottawa’s artistic community, along with fellow artists Tolgesy, Trottier, and Boyd. They all exhibited at Blue Barn Gallery, forming what Trottier’s daughter Denise has referred to as “Ottawa’s Group of Seven.” Critics W.Q. Ketchum of the Ottawa Journal and Carl Weiselberger of the Ottawa Citizen were generally supportive of the gallery’s packed exhibition program. Weiselberger wrote in a January 1965 column about the “lively spring and summer season of exhibitions… being prepared,” including one-person shows by Jean McEwen (1923–1999), Takao Tanabe (b.1926) (whose portrait de Kergommeaux drew in 1955), Tony Urquhart (1934–2022), Richard Gorman (1935–2010), and others. The exhibitions attracted many collectors, including John and Mary Robertson, Glenn and Barbara McInnes, Hans and Bela Adler, and Dick and Ruth Bell.

Blue Barn’s greatest impact was probably on Carleton University, which had moved to a campus on the Rideau Canal. Trottier had been working as an artistic adviser and studio instructor there, but when he left Ottawa in 1965, de Kergommeaux inherited his post. He convinced faculty members to hang contemporary paintings from Blue Barn’s inventory in office spaces and asked fellow artists to donate their works. When Carleton finally established its own art gallery in 1992, these pieces would form the core of the university art collection.

Blue Barn Gallery closed in 1967 and was succeeded by Lofthouse Gallery, itself a key site for contemporary art, and by Wells Gallery, which for many years showcased the work of local artists.

1969: Local vs. National: Artists’ Protest and the National Gallery’s Role

Ottawa’s cultural life has been shaped by the existence of national institutions including the National Gallery of Canada, the National Archives, and the National Library. For many Ottawans, there was no need for a municipal art gallery, museum, or archives when the national capital already provided them with access to such institutions at little or no cost. But local artists increasingly came to believe, beginning in the 1950s, that the Canadian focus on the National Gallery came at price, with their work being largely ignored in favour of art from other metropolitan centres.

Like others before him, Duncan de Kergommeaux had first moved to Ottawa in 1954 to work in a public service job while pursuing a desire to “paint freely” in his spare time. He initially viewed the era with optimism, noting, “By the mid-1950s, the nation was experiencing a level of prosperity that allowed people to make a greater commitment to the arts. Ordinary people were starting to write poetry, visit the galleries and contemplate issues beyond their basic needs. Economic prosperity led to a period of cultural liberation.” He encountered an Ottawa scene in which artists, led by Henri Masson (1907–1996), Jean-Philippe Dallaire (1916–1965), and Gerald Trottier, had begun to take up abstraction, contemporary palettes, and social realism. De Kergommeaux and James Boyd both explored traditional subjects in innovative forms, as seen in de Kergommeaux’s Painting from a Pine Forest, No.1, 1957. Boyd was seeking to investigate the natural world in non-realistic form, an approach exemplified by Anthropomorphic Fusion No. 2, 1958. The sculptor Victor Tolgesy was also moving toward a more broadly non-representational sculptural style by the end of the decade. Ottawa artists were building a strong network, particularly with the Montreal scene, as they displayed and worked in both cities, and increasingly with Toronto as well.

When Alan Jarvis was appointed as the National Gallery director in 1955, many hoped that his energy, connections, and charm would bring new life to the institution and local scene. Jarvis promoted the idea of “a museum without walls,” brought in contemporary art, and shook the general public out of a period of national complacency, but he was hounded out of office in 1959, just before the gallery moved from the Victoria Memorial Museum to the Lorne Building in 1960. His replacement, Charles Comfort, could be relied upon to maintain the status quo. Under his administration, thanks to the excellent curatorial staff whom Jarvis had nurtured, the gallery maintained a steady pace of exhibitions. But there were fewer major acquisitions, and Ottawa artists, who had seen their works enter the national collection in greater numbers during Jarvis’s tenure, felt left out.

In 1966, new director Jean Sutherland Boggs sought to revitalize the gallery, sponsoring more touring exhibitions and hiring a number of dynamic new curators, including Brydon Smith in contemporary art, James Borcoman in photography, and Pierre Théberge, Dennis Reid, and Charles Hill in Canadian art. The energy of Expo 67 and other events held in Canada’s centennial year also provided many opportunities for artists, with the works of such rising stars as Christiane Pflug (1936–1972), Jack Chambers (1931–1978), Greg Curnoe (1936–1992), Michael Snow (b.1928), and Joyce Wieland (1930–1998) gaining currency—Wieland’s Balling, 1961, and Snow’s Lac Clair, 1960, were important acquisitions during this period. Some Ottawa artists believed that not enough was being done for them and were determined to try and change the perception of art within the city itself.

A protest planned by de Kergommeaux and Tolgesy took place in June 1969, when one of Tolgesy’s sculptures was mounted on an empty plinth on Wellington Street, west of the Parliament Buildings. It remained there for two days before being removed. The protest was widely covered in the press as a tangible expression of the artists’ frustration. Boggs publicly admitted that the National Gallery did not actively seek out local talent, but she pointed to its sponsorship of various exhibitions, such as 1965’s Ottawa Collects Sculpture, which had included works such as Birds of Welcome, by Art Price (1918–2008), and to the touring exhibitions of works by de Kergommeaux and Georges de Niverville in 1967–68.

The protest became a legendary moment in the arts in Ottawa, although it failed to ignite any immediate action. The work of artists from Montreal, Toronto, Vancouver, and increasingly London, Ontario, dominated the gallery’s walls through the 1970s, but Ottawa had yet to build a permanent institution to celebrate the city’s artistic heritage.

1971: A New Arts Building at the University of Ottawa

Many internationally recognized artists began their careers in the corridors of the fine arts building of the University of Ottawa. By 1965, the institution had evolved from its beginnings as a Catholic teaching college founded in 1848. To become eligible for government subsidies to develop facilities and programs, it divided into Catholic Saint Paul University and the sectarian University of Ottawa. In 1970, art studio programs, as well as art history and photography courses, were moved into a building at 100 Laurier Avenue East, built in 1894, now the oldest building on the university campus.

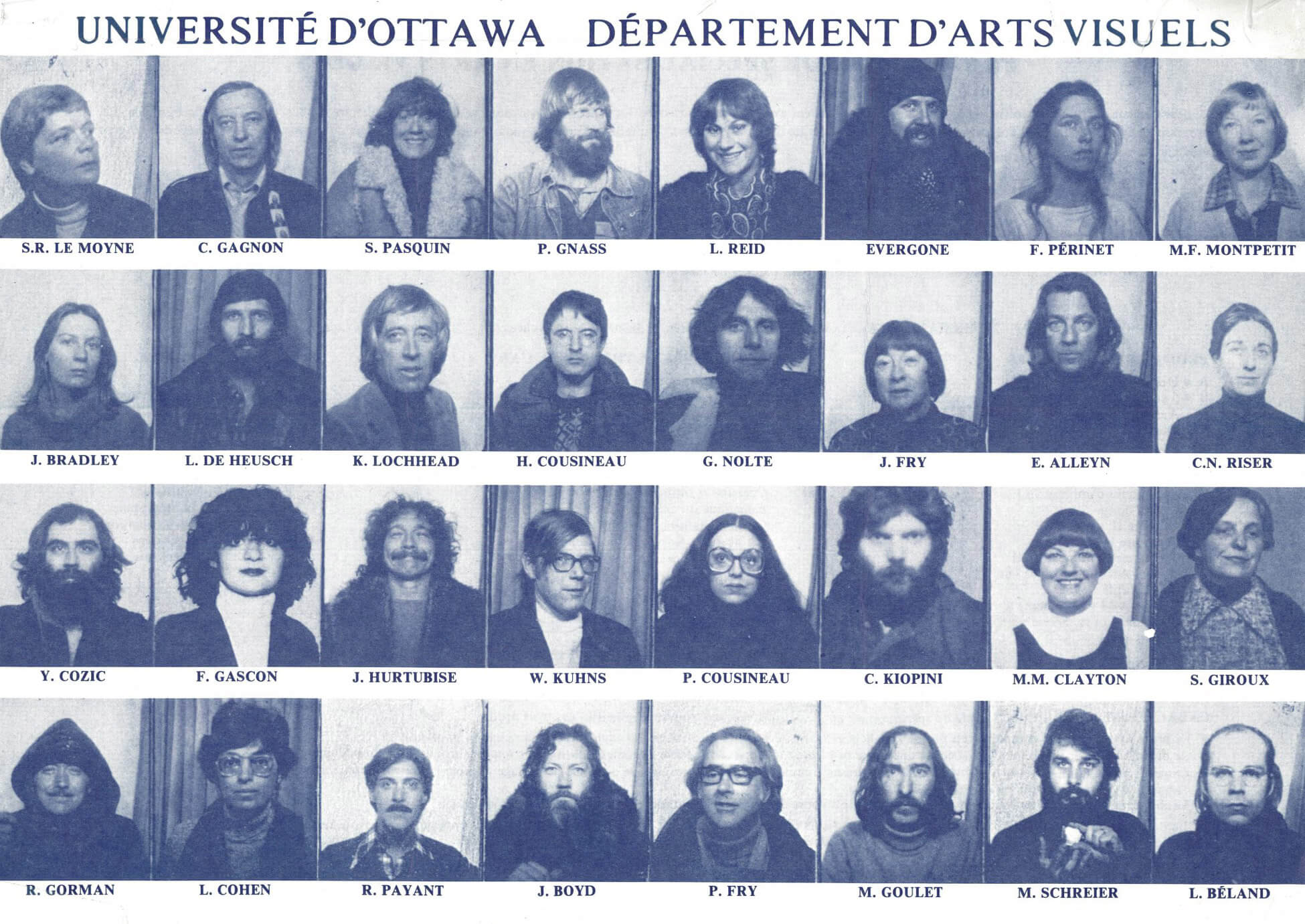

Four years after the move, in response to increasing interest in post-secondary education, the university established a visual arts department that offered a bachelor’s degree in fine arts as well as programs in art history. Its first director, Suzanne Rivard-Lemoyne, formalized the program and hired an impressive range of instructors. The teaching staff included artists Richard Gorman and James Boyd, photographer Alain Desvergnes (1931–2020), and art historian Constance Naubert-Riser.

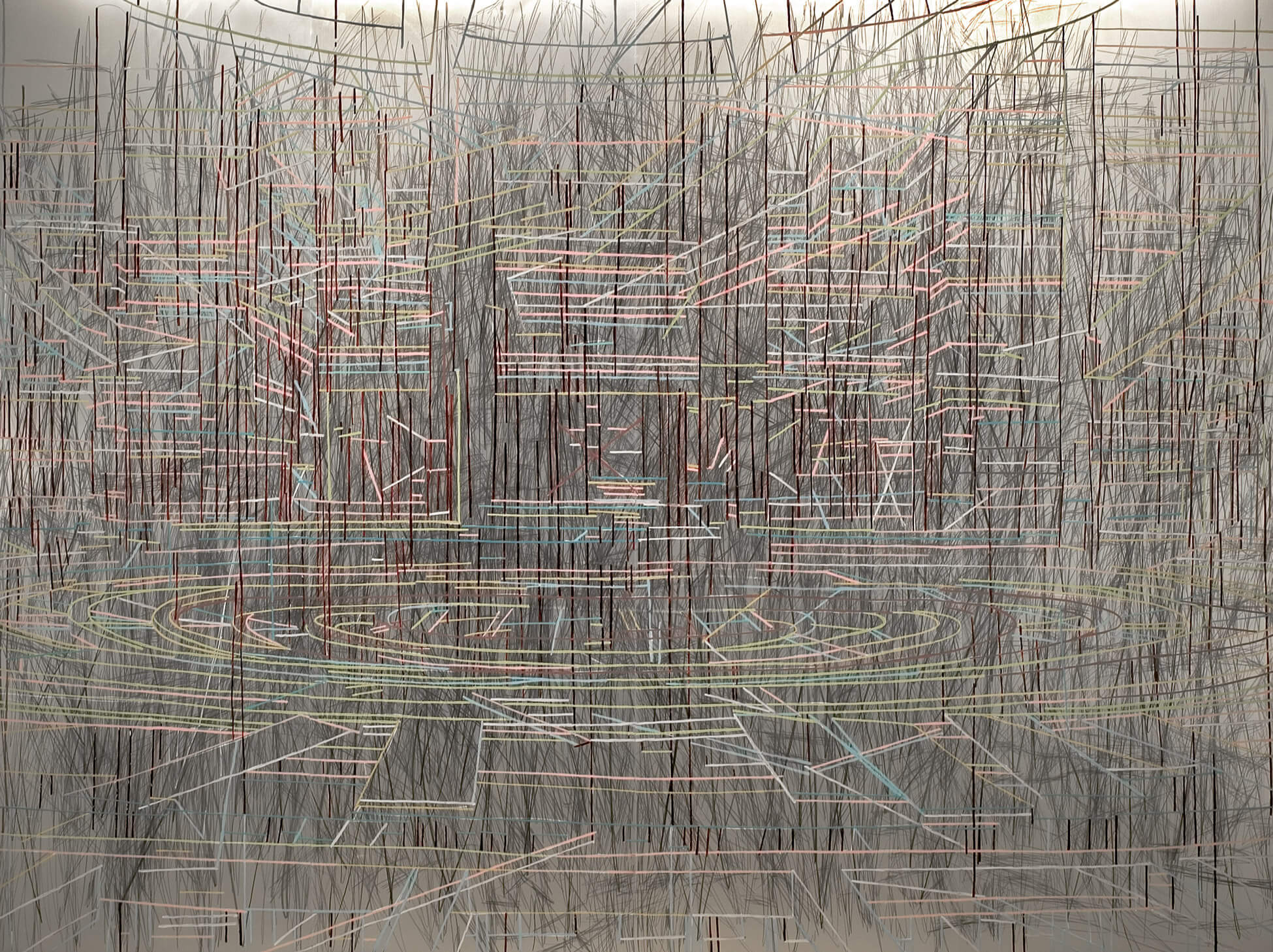

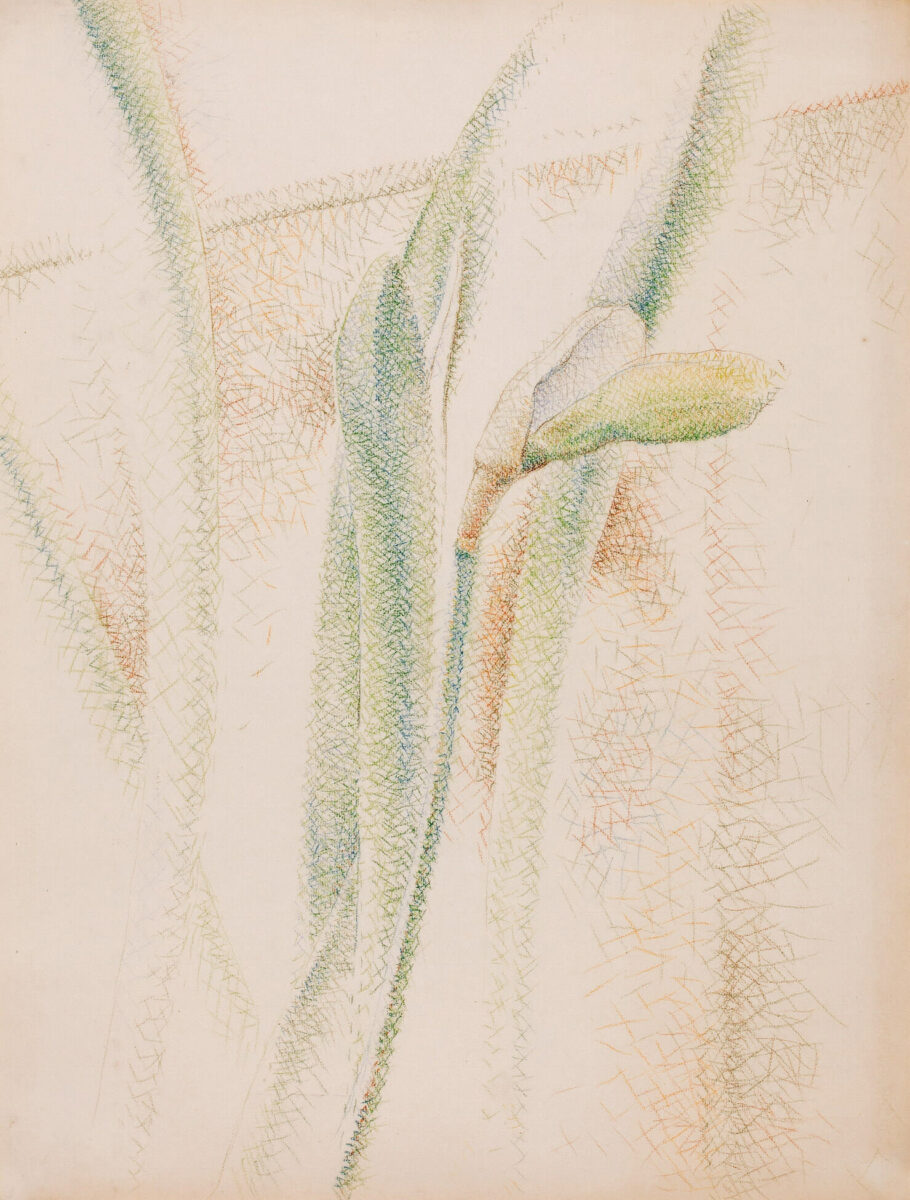

As the program expanded, it also hired Ottawa-born Leslie Reid (b.1947) as well as Michael Schreier (b.1949), Edmund Alleyn (1931–2004), Lynne Cohen (1944–2014), Kenneth Lochhead (1926–2006), Charles Gagnon (1934–2003), and Gunter Nolte (1938–2000). By the mid-1970s, there were more than thirty teaching staff. A list of the painters, sculptors, filmmakers, and photographers who have taught in the Department of Visual Arts includes some of Canada’s most celebrated artists. In addition to teaching, many were making art in the city—Cohen’s Military Installation, 1999, is one notable example—and displaying their work in exhibitions and public installations, such as Boyd’s Les Yeux, 1973.

The program’s graduates, among them such notable individuals as Ron Noganosh (1949–2017), Eliza Griffiths (b.1965), Joseph-Alexandre Castonguay (b.1968), Cara Tierney (b.1979), and Chantal Gervais (b.1965), have distinguished themselves in different communities associated with fine art. The BFA program continues to teach the more traditional disciplines of drawing, painting, sculpture, and photography, but it has also branched into new technologies, including media arts.

In 2006, the Department of Visual Arts introduced a Master’s of Fine Arts program—another enormous contribution to the growth of the Ottawa arts scene. Artist Jinny Yu (b.1976) and critic Penny Cousineau-Levine have been among the directors of this program. Some graduates have in turn become faculty professors. Today the department continues to be a significant force in the artistic milieu of the city.

1973: Sussex Annex Works Gallery

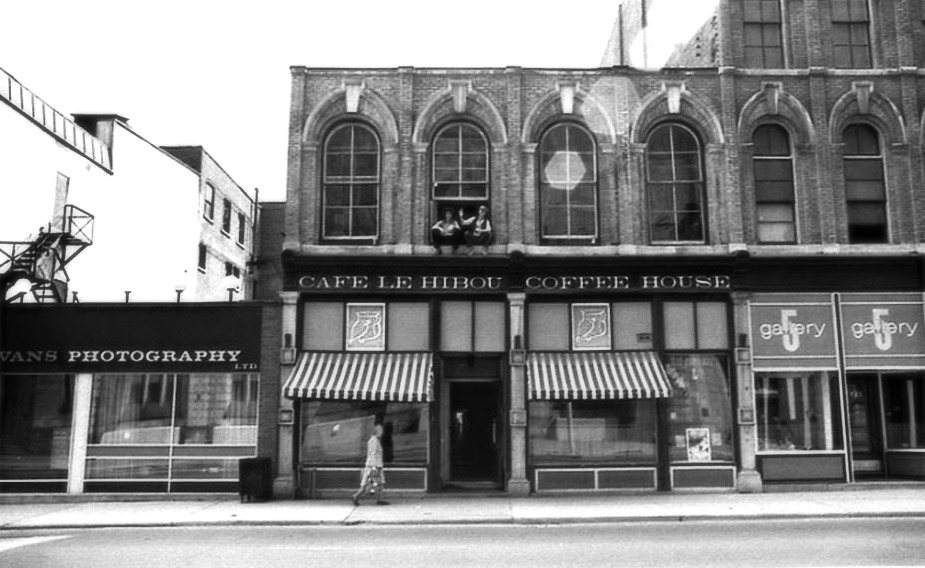

Sussex Annex Works (SAW) Gallery, one of the earliest artist-run organizations in Canada, has only formally existed since 1973, but it originated from the avant-garde scene centred on the 1960s coffee house Le Hibou. Artist Pat Durr (b.1939) recalls

It was the summer of 1964…. The most exciting thing about downtown Ottawa was the train leaving for Montreal… [but] on Sussex an oasis called Le Hibou buzzed with conversation until the late hours. Le Hibou was Hull’s only rival on this side of the river: Hull, the magic island, where rock and roll and jazz clubs flourished until early morning…. In the late 1960s, a small group of young artists cleaned up the second floor of Le Hibou in anticipation of holding regular exhibitions. They also offered facilities for photography, silkscreen and offset printing. They called themselves Sussex Annex Works.

SAW’s original co-founders in late 1972 were photographer Peter W. Lamb and painter Arthur II (b.1950), who were joined by several others, including photographer John Garner (1897–1995) and sculptor Alyx Jones. Le Hibou owner Pierre-Paul Lafrenière came up with the name Sussex Annex Works. Dennis Tourbin, Marlene Creates (b.1952), and video artist Michael Balser (1952–2002) would become involved later in the 1970s.

From the outset, SAW was unique in being an artist-run space. It supported politically and socially engaged art, especially performance art, such as Tourbin’s FLQ/CBC piece, staged originally in 1977 and remounted in 1995 in the midst of the Quebec referendum, generating enormous controversy. Later projects, including Of Intimate Silence, a 1978 exhibition featuring prints by Richard Nigro (b.1950), as well as performances by Nigro and Mark Frutkin (b.1948) in 1981, also attracted public attention. SAW proved to be a model for other Canadian-run artist centres, such as Ottawa’s Gallery 101, a non-profit gallery formed in 1979, and Axenéo7, founded in Gatineau in 1983.

All these centres were committed to “contemporary art, which is socially engaged and, indeed, risky and oppositional,” in the words of Creates. During the 1980s, both SAW and Gallery 101 organized performances, poetry readings, and music events alongside their regular exhibition programming. Media arts—including sound art, video, and experimental cinema—became an important part of programming in all three venues in the 1990s.

SAW hosted exhibitions by many of Canada’s best-known artists in the early stages of their careers. In 1981, SAW Video co-operative was founded to support independent video artists and documentarians. SAW also launched Club SAW, which evolved into the most important multidisciplinary space in the region. In 1989, the three entities moved into the historic Arts Court building and began a long, co-operative relationship with the Ottawa Art Gallery. In 2001, SAW Gallery and SAW Video became separate organizations, but they remain based at Arts Court and continue to collaborate.

By 2014, SAW Gallery was hosting more than 150 cultural events a year and welcoming more than 35,000 visitors. It is still an innovative multidisciplinary venue, hosting programming ranging from the Ottawa International Animation Festival to the Mòshkamo Indigenous Arts Festival. The inaugural exhibition in SAW’s renovated venue, Sex Life: Homoeroticism in Drawing, opened in August 2019 and honoured the gallery’s roots as an activist space. As a nationally recognized artist-run centre, it has contributed immensely to the Ottawa region’s cultural landscape, supporting generations of artists.

1975: Visual Arts Ottawa Survey Exhibition No. 1

In May 1975, a group calling itself Visual Arts Ottawa organized an exhibition of more than 300 works by 156 different artists at the Hall of Commerce Building in Lansdowne Park. The opening attracted more than 1,400 people, and thousands more saw the show before it closed on June 28. Its impact was profound, creating a long-term effect on the visibility of the region’s artists.

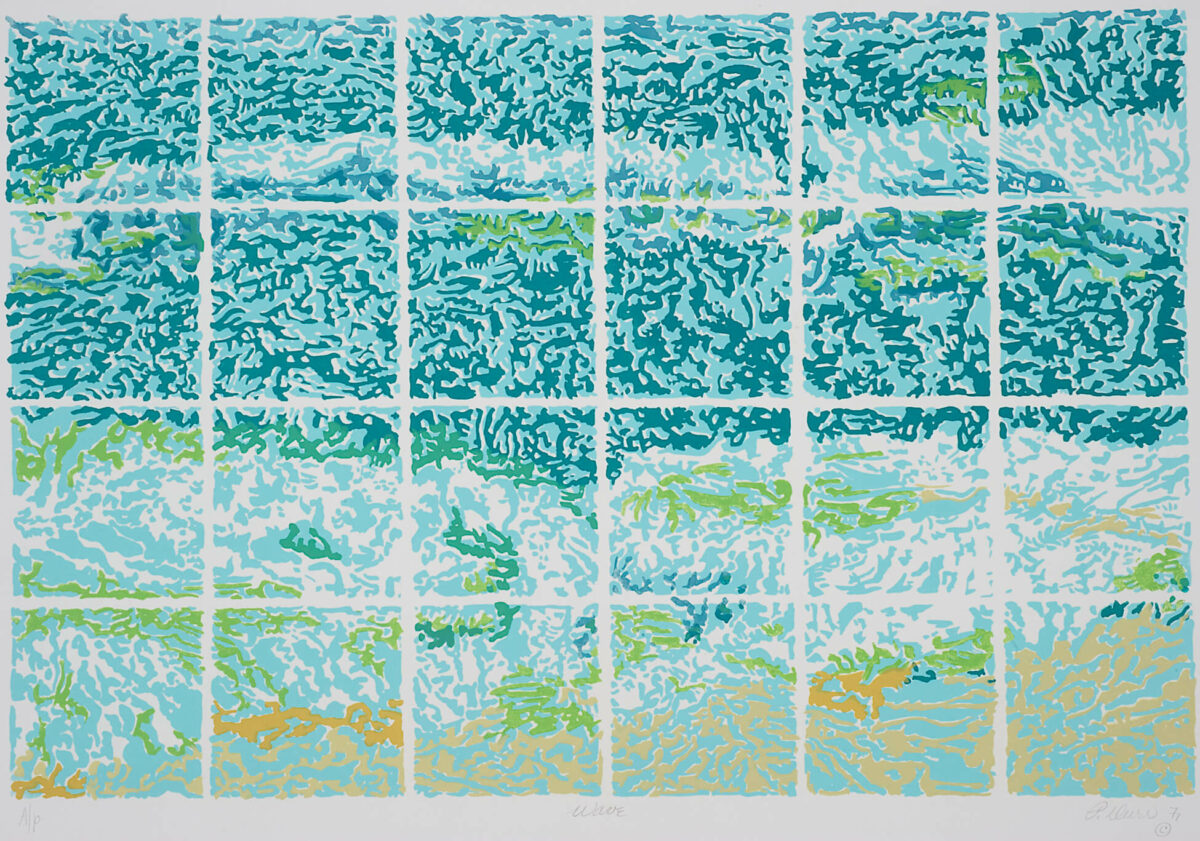

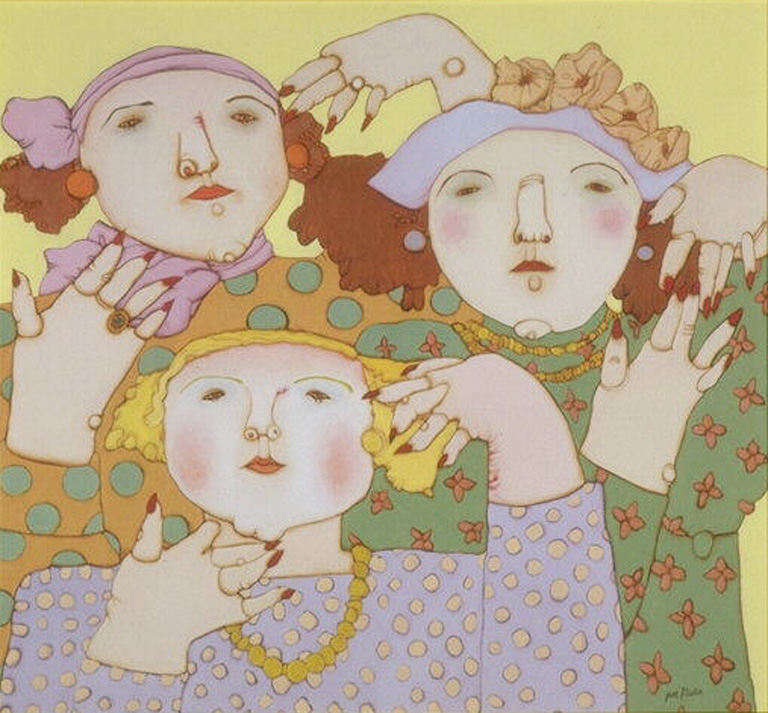

In the early 1970s, the ongoing failure of municipal leaders to respond to the need for a city-run art gallery frustrated many art lovers, who began lobbying for action since the transfer of the O.J. Firestone Collection to the Ontario Heritage Foundation in 1972. Visual Arts Ottawa, formed in 1974, was led by artists Victor Tolgesy, Gerald Trottier, Pat Durr, James Boyd, Michael Schreier, Jerry Grey (b.1940), and Hilde Schreier (b.1926); arts supporters Anna Babinska, Rosita Tovell, and Suzanne Joubert; dealers John Robertson, Jean-Claude Bergeron, Claire Wallack, and Barbara Ensor; and collectors O.J. and Isobel Firestone and Mrs. G.H. Southam. The Globe and Mail later summarized their efforts with the headline, “Ottawa valley artists bid… to get rid of the backwater syndrome.” Such a reputation was entirely undeserved: many of the city’s artists had been creating highly contemporary work for years, as can be seen in Trottier’s mural The Pilgrimage of Man, 1962, Durr’s Wave Prints, 1971, and Three Women, 1972, by Jane Martin (b.1943), to name only a few examples.

Visual Arts Ottawa invited local artists to submit works for the proposed exhibition. Almost 600 accepted the challenge, and three jury members sifted through more than 2,000 entries. Their final selection included paintings, photographs, sculptures, and examples of craft work, such as textiles and wall hangings.

The event crossed geographical and linguistic boundaries: anglophone and francophone artists from both the sides of the river participated. Unfortunately, there was little representation from visible minorities or Indigenous artists. Still, it marked an important turning point in the history of art in Ottawa. While there had been exhibitions in the city for decades, no other was as large, nor did they draw upon such a range of important players in the cultural scene. The show galvanized the artistic community into longer-term action. Within two years, the rebranded Ottawa School of Art would move into more high-profile quarters in the ByWard Market. By 1980, Ottawa mayor Marion Dewar had convened a special advisory group including Durr, Grey, and Richard Nigro, which recommended the creation of a municipal arts centre with a permanent art collection.

1987: Victor Tolgesy Arts Award

After arriving in Ottawa in 1951 from his native Hungary, the energetic and creative Victor Tolgesy played a key role in promoting his own work and that of his fellow artists in the community and the wider national scene. His unexpected death in January 1980 at the age of fifty-one deprived the city of both a talented sculptor as well as one of its cultural leaders. The city of Ottawa, in co-operation with the Ottawa Arts Council, inaugurated the Victor Tolgesy Arts Award in 1987. It recognizes the accomplishments of residents who, like its namesake, have contributed substantially to enriching local cultural life.

To be eligible for the Tolgesy Award, candidates had to be nominated by an individual or group and have lived in the National Capital Region (defined as seventy-five kilometres from Parliament Hill) for the previous five years. The first award in 1987 went to not one but two recipients: long-time arts supporter Trudi Le Caine, who had supported musical education since 1942 and had been involved with Le Groupe de la Place Royale dance company and Opera Lyra Ottawa; and former gallery owner John Robertson, who had been active as an arts administrator, dealer, and collector for several decades.

In 1988, the award was given to artist and arts policy champion Pat Durr. Since that time, a series of recipients have been named, including artists Jennifer Dickson (b.1936) (2001) and Robert Hyndman (2003); and arts administrators Penny McCann, the director of SAW Video (2006); Mela Constantinidi, director of the Ottawa Art Gallery (2010); Victoria Henry, director of the Canada Council Art Bank (2014); and Alexandra Badzak, also director of the Ottawa Art Gallery (2019).

The Tolgesy Award continues to be a tangible and important honour, not just for artists and arts supporters, but also for individuals working in theatre, music, and other disciplines. Each winner since 1987 has received a bronze cast of Tolgesy’s sculpture Seed and Flower, 1963, as well as a cash prize of $5,000.

1988: Gallery at Arts Court / Ottawa Art Gallery

The Ottawa Art Gallery (OAG), originally named the Gallery at Arts Court, represents the culmination of a long-time vision for an institution devoted to acquiring the works of artists with strong regional ties and to exhibiting works relating to Ottawa. Art history students in the 1970s found it difficult to believe that the city still lacked a space where the works of artists that they knew personally, such as Robert Hyndman or Juan Geuer (1917–2009), could be found, or that the city actually had a history of art at all. When the Gallery at Arts Court was finally established in 1988, one of its major goals was to build a contemporary art collection and to provide exhibition spaces for Ottawa-area artists within the confines of Arts Court itself, a converted courthouse building. In 2018, a new gallery building opened that was capable of hosting national and international touring shows.

By the mid-1970s, pressure had begun to grow for a city art gallery, due to a variety of concerns: the realization that the National Gallery had a national rather than local mandate; the donation of the O.J. Firestone Collection to the Ontario Heritage Foundation, because no municipal body existed to which it could be transferred; and the growing artistic and cultural scene that lacked a dedicated exhibition space.

The mayor’s Advisory Committee on the Arts recommended the establishment of the Ottawa Arts Council in 1982, which in turn proposed a municipal gallery. In 1985, the city initiated one of the first visual art policies and programs in Canada, including a Visual Arts Office that, under the management of ex–National Gallery curator Mayo Graham, developed an art acquisition fund and a percent-for-art program for all new civic buildings. The office also enabled the city to bid, successfully, for the stewardship of the Firestone Collection of Canadian Art, which was transferred to Ottawa in 1991.

At the same time, the Ottawa Arts Centre Foundation had advocated for the renovation of the former county courthouse as a home for local arts organizations. This body brought together many artists, community activists, and collectors, among them Graham, Pat Durr, Susan Geraldine Taylor, Leta Cormier (b.1948), Susan Annis, Glenn and Barbara McInnes, Lawson Hunter, and Glen Bloom. In 1988 their efforts succeeded, and the Gallery at Arts Court opened to the public, with its initial exhibition featuring the work of fourteen artists, including Durr, Alex Wyse (b.1938), Richard Nigro, Ron Noganosh, Justin Wonnacott (b.1950), and Russell Yuristy (b.1936).

On June 6, 1992, the renamed Ottawa Art Gallery inaugurated a newly renovated space within the courthouse building with the exhibition Treasures from the Firestone Art Collection. This gift had brought major works to the gallery, among them Evergreen, 1958, by Kazuo Nakamura (1926–2002) and In The Nickel Belt, 1928, by Franklin Carmichael (1890–1945). An art rental service was launched, which continues to operate to this day, generating acquisition funding and showcasing local artists. In 1993, Mela Constantinidi succeeded Graham. During her tenure, the OAG embarked on an ambitious historical and contemporary program.

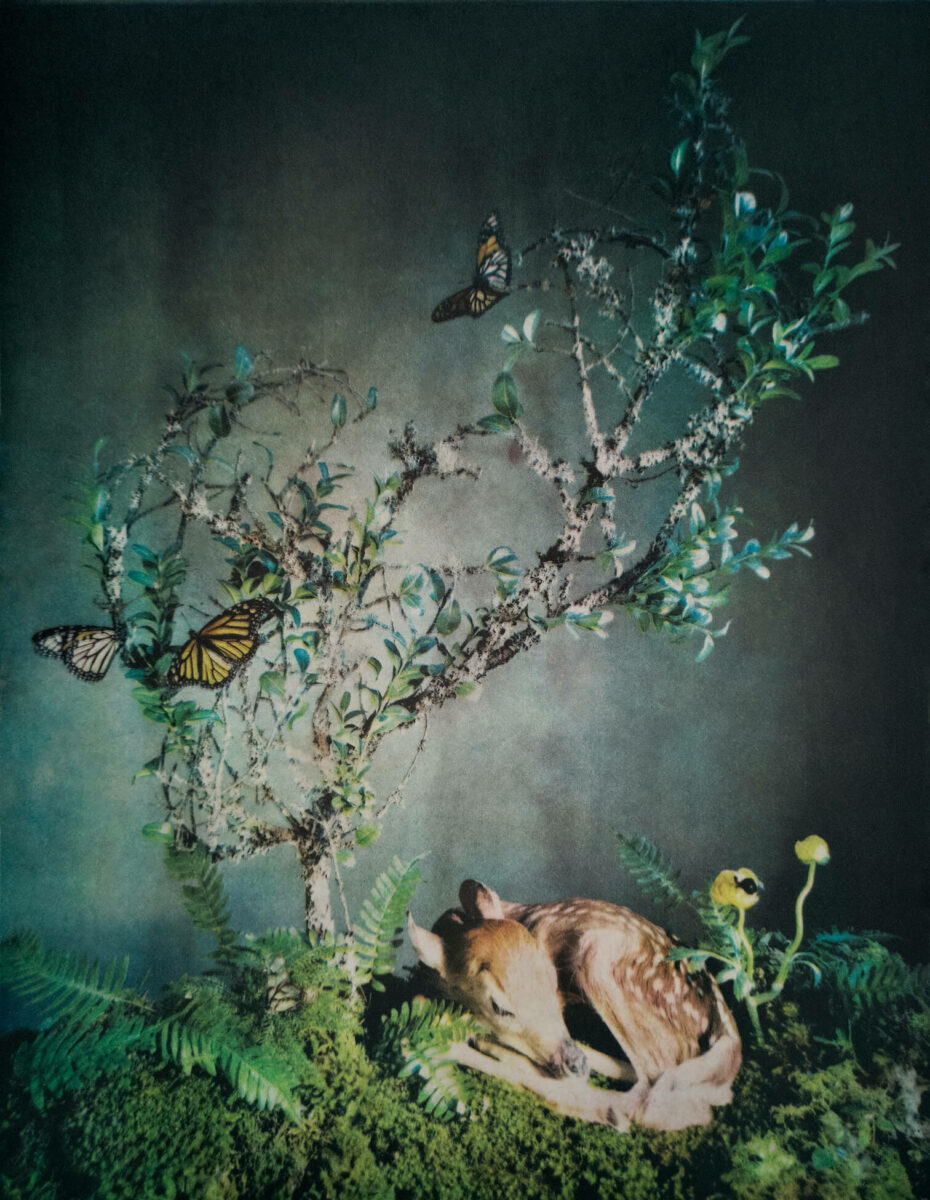

Three major exhibitions on the history of art in the Ottawa region appeared—in 1993, 1994, and 1995. As well, major surveys of contemporary art took place several times a year. Retrospectives highlighting historical figures Franklin Brownell, Gerald Trottier, Henri Masson, and Alma Duncan, and contemporary artists Jennifer Dickson, Catherine Richards (b.1952), Max Dean (b.1949), Adrian Göllner (b.1964), and Evergon (b.1946) were held. Group and themed shows were organized, and special exhibitions related to the Firestone Collection of Canadian Art also appeared regularly. The OAG has championed the work of Indigenous artists, featuring the work of Noganosh, Jeff Thomas (b.1956), Frank Shebageget (b.1972), and Greg Hill (b.1967).

By 2010, the OAG had become known for its experiments in curatorial practice. That year, a new director, Alexandra Badzak, took over and guided the gallery’s ambitious plan to build a large-scale addition, which opened in April 2018. This expansion was marked by the hugely successful inaugural exhibition Àdisòkàmagan / Nous connaître un peu nous-mêmes / We’ll All Become Stories: A Survey of Art in the Ottawa-Gatineau Region. The gallery has given Ottawa a much-needed landmark building to highlight its art and artists.

1992: Carleton University Art Gallery

Carleton University was founded as a college in 1942. Only a year later, it introduced art history courses, taught by National Gallery curator Robert Hubbard. The art history department was established in 1966, under the direction of Mary-Louise Campbell. In the 1970s and 1980s, there were several proposals for a university art gallery, with support from such individuals as professor Nan Griffiths. The expansion of St. Patrick’s College campus provided the impetus for an institutional space, and in September 1992 the Carleton University Art Gallery (CUAG) opened, led by former National Gallery acting director Michael Bell.

The collection had been a work in progress for several decades. In the 1960s, the university had introduced a studio art program under artist Gerald Trottier, who began to advise on efforts to build an institutional art collection. His successor, Duncan de Kergommeaux, expanded it to more than eighty pieces by 1970, when the first proposal for an art gallery appeared. With the aims of supporting courses in art history and museology, enriching other academic programs, responding to the cultural needs of the community, and acting as a site to store and display the university’s art collection, it was ambitious.

From 1969 to 1974, Carleton hosted the annual Canadian Printmakers’ Showcase, resulting in more acquisitions, among them pieces by Greg Curnoe. A decade later, Ottawa collectors Frances and Jack Barwick gave the university fifty-seven artworks, a collection that included treasures such as Daffodil, c.1940, by Lionel LeMoine FitzGerald (1890–1956) and Bombed Out (Refugees), c.1943, by Will Ogilvie (1901–1989). They also donated substantial funding, and further contributions from the community enabled the opening of CUAG in 1992. Bell elicited additional donations from artists and collectors, including John and Mary Robertson.

Diana Nemiroff, Bell’s successor, built on the gallery’s reputation with a strong program of eight to twelve exhibitions annually. The current director, Sandra Dyck, has maintained this momentum, exploring the possibilities of diverse media, opening the institution to a broader range of subjects, working with BIPOC artists and curators, and building public programs. Emerging cultural workers, including students, play a significant role in organizing exhibitions and public programs.

The primary focus has been Canadian contemporary art, including shows featuring Lynne Cohen (2006) and Michèle Provost (b.1957) (2010). Exhibitions of the work of Frank Shebageget, Carl Beam (1943–2005), Robert Houle (b.1947), Shuvinai Ashoona (b.1961), and Christi Belcourt (b.1966) demonstrate the gallery’s ongoing commitment to Indigenous artists. Finally, the histories of specific Ottawa artists have been explored in Pegi Nicol MacLeod: A Life in Art (2005), A Pilgrim’s Progress: The Life and Art of Gerald Trottier (2006), Meryl McMaster: Confluence (2016), and Alootook Ipellie: Walking Both Sides of an Invisible Border (2018), and they have created online programming such as Future Rivers: Film and Video from the Desert River (2021), an initiative showcasing films by Algonquin artists Russell Ratt Brascoupe and Craig Commanda, among others.

Many Carleton graduates, guided by eminent scholars such as Ruth Phillips and the late Natalie Luckyj, now fill vital roles in the Canadian artistic community. A whole generation of curators attests to the success of the program associated with the art gallery.

2001: City of Ottawa Public Art Program

Though Ottawa has had a visual arts policy since 1985, after the city amalgamated with nearby suburbs in 2001 it established a new Public Art Program. Its goals were to make the public aware of Ottawa’s extraordinary visual art history and introduce many younger artists to a wider audience. It has also provided opportunities for mid-career and established professional artists, especially those who are from First Nations, Inuit, Métis, francophone, Black, Asian, and new Canadian communities.

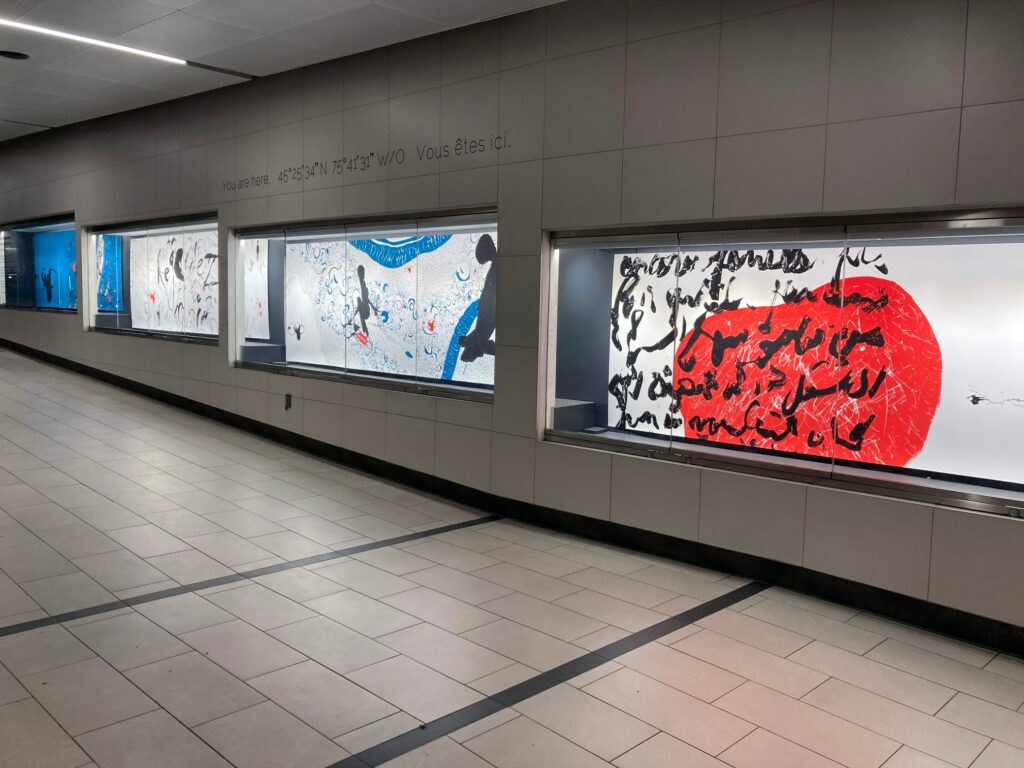

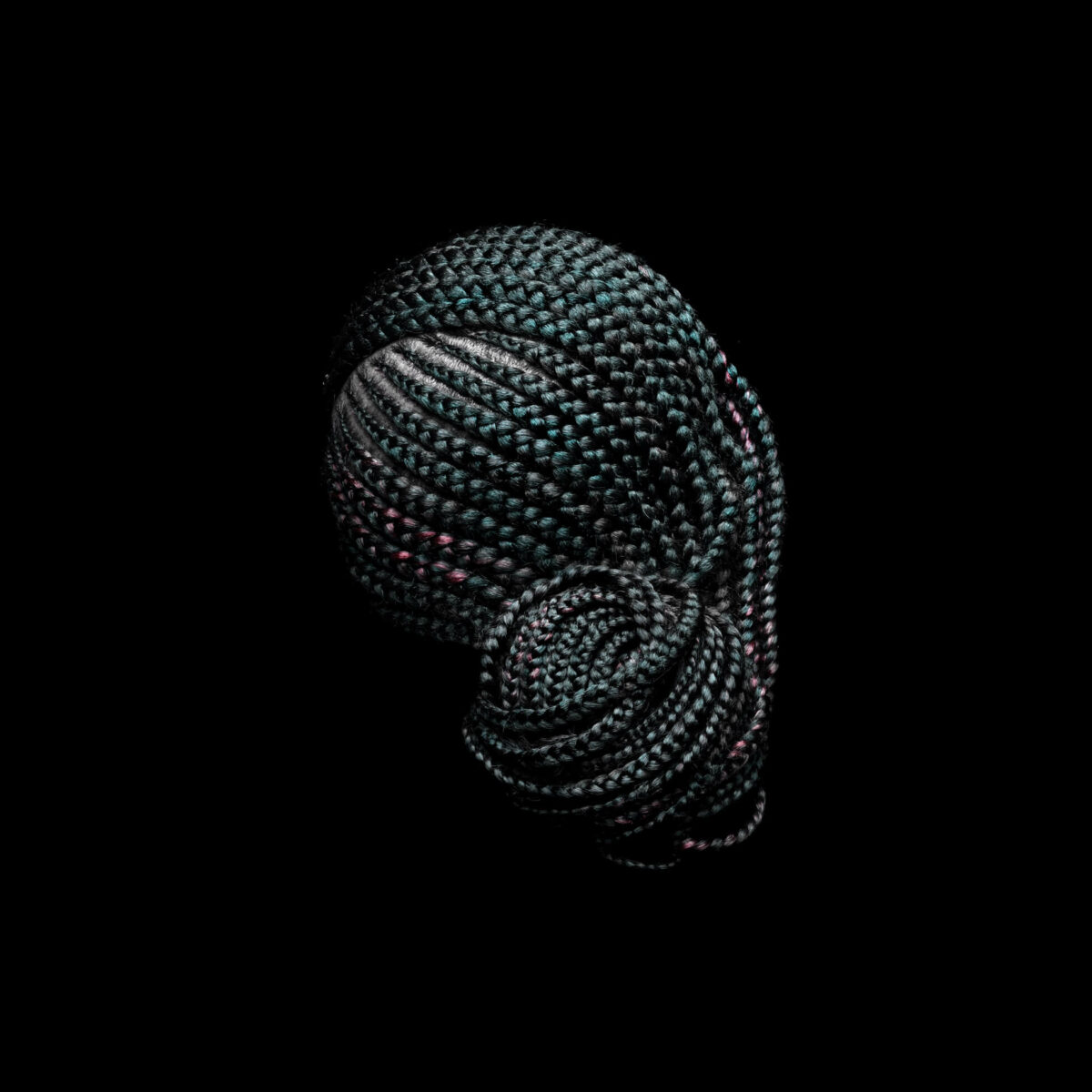

The collection is shown in exhibitions and events at three major spaces: the Karsh-Masson Gallery, the City Hall Art Gallery, and Corridor 45|75. Works are also displayed in many public buildings, on city streets and in parks, and even in the transit system. For example, Juan Geuer’s Carnavelesque, 1994, is installed at a bus station, and being | née | être | born, 2021, by Mana Rouholamini is in an underground passageway in the light rail system.

The Public Art Program has been emulated by Calgary, Edmonton, Moncton, Montreal, Surrey, Toronto, Kingston, and Vancouver. Ottawa’s art collection has now grown to more than 3,000 artworks, created by more than 800 artists. People pass by many of these pieces every day as they walk, cycle, ride a bus, or drive around the city. Some, like Strathcona’s Folly, 1995, by Stephen Brathwaite (b.1949), evoke medieval ruins, while others, like Rise/Levée/Kògahamog, 2020, by Amy Thompson, invite contemplation.

Not all public art is sculptural or painterly, nor is it on permanent display. The city also acquires what it classifies as “moveable” art, which consists of works such as drawings by Annie Pootoogook (1969–2016), or photographs by Jennifer Dickson, Meryl McMaster, and Yousuf Karsh (1908–2002). The collection stands out as a successful example of former National Gallery of Canada director Alan Jarvis’s 1950s call to build a “museum without walls.“

2003: The Karsh Award

Two of Ottawa’s most famous photographers were Yousuf and Malak Karsh, Armenian-born brothers who came to Canada in the 1920s. Yousuf, eventually known only as “Karsh of Ottawa,” built an international reputation, famous for his studies of Winston Churchill, Ernest Hemingway, Pablo Casals, and many others, in addition to his portraits of Canadian political figures, such as Pierre Elliott Trudeau, or cultural leaders, such as Robertson Davies. Malak Karsh (1915–2001), who adopted the singular name “Malak,” concentrated on still life, landscape, and genre work. One of his photographs was reproduced on Canadian currency, but he is also known for images promoting the annual Canadian Tulip Festival in Ottawa. Created in 2003, the Karsh Award honours the brothers’ enormous contribution.

The Karsh Award also speaks to the importance of photography in the history of art in Ottawa. The large-scale photographs showing the construction of the Parliament Buildings in the 1860s by Samuel McLaughlin (1926–1914) and William J. Topley’s composite photographs of Governor General’s Balls in the 1870s attest to the search for excellence and innovation in photography in the nineteenth century. The Photographic Art Club’s explorations of pictorialism from 1904 onwards and the annual International Salon of Photographic Art held at the National Gallery of Canada from 1934 to 1940 pushed the boundaries of the medium. New talent has been fostered by the University of Ottawa fine arts program that employed such renowned instructors as Michael Schreier, Lynne Cohen, and Evergon, who in turn passed on their passion to practitioners such as Chantal Gervais. The foundation of the School of the Photographic Arts of Ottawa in 2005 served to reinforce how consequential this medium is.

The Karsh Award is given to an individual whom the adjudicators deem to have created an outstanding body of work and whose contribution to lens-based art is of deep significance. A cash prize is given, as is an opportunity to hold an exhibition at the city’s Karsh-Masson Gallery, which has held many group shows, such as Holding Pattern (2021). Past award winners include Lorraine Gilbert (b.1955) (2003), Jeff Thomas (2008), Tony Fouhse (b.1954) (2010), Rosalie Favell (b.1958) (2012), Schreier (2016), and Andrew Wright (2019). Their works have had a major impact on artistic practice and the city, with explorations of such issues as environmental degradation, the recovery of Indigenous history, public art, and life on the edge of society. In 2022, the Karsh Award program also recognized emerging artists, with Wright selecting Stéphane Alexis, Shelby Lisk, and Neeko Paluzzi as honorees.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements