For many first-time visitors, Ottawa comes as a surprise. Drawn to the city as a national capital, they seek out the Parliament Buildings, the war memorials, the national museums, the boat cruises on the Ottawa River and the Rideau Canal, and other cultural amenities. They also discover a metropolis in the middle of a northern wilderness, with stunning geographic features and a diverse, well-educated, and multilingual population. One of Canada’s largest cities, Ottawa has a history that is little known to most Canadians. A place where Indigenous people have met since time immemorial, it was a modest settlement until its random selection as the country’s capital by a Queen who never set eyes on it. Since then, Canada’s rapid growth in the nineteenth century, two World Wars, and surges in immigration have all left their mark on the city and shaped Ottawa’s cultural landscape today.

First Nations Culture in the Ottawa Region

Ottawa exists because of its unique geographical position: it lies at the junction of the Gatineau, Rideau, and Ottawa Rivers—which, along with their tributaries, extend for thousands of kilometres into the continent—and on a geological fault line, which created the Chaudière Falls. This region has been the ancestral territory of the Algonquin (Anishinābe) peoples for millennia. Their seasonal movements included stays at winter encampments in the remote highlands on either side of the Ottawa River, known to the Anishinābe as the Kichi Sibi, and summer fishing and trading camps at the mouths of the various tributaries. Such transitory activities resulted in a limited number of identifiable cultural artifacts from the Ottawa-Gatineau region, and only a few pictographic representations found at Mazinaw Lake, Oiseau Rock on the upper Ottawa River, or elsewhere in eastern Ontario have survived. Floods, erosion, and more recent human activity may have effaced others that existed. Little is known about their creators, but the images may have had spiritual and ritual purposes.

In addition to pictographs, Anishinābe culture also included the decoration of clothing and other belongings. Geometric designs may have had either secular or personal meaning, but they also may have fulfilled sacred or religious purposes. Women created clothing, wove baskets, carved tools, and made clay pottery, and their artistry was often complex and beautiful. Design patterns survived European contact, as Indigenous materials (quills and pigments, copper ornaments, shells) were gradually replaced by European-manufactured goods (beads, silver, buttons), and traditional knowledge can be seen in works such as Wigwemod (bark container), c.1925, by an unknown artist, and Lena Nottaway’s Tikinagan (baby carrier), 1962.

While the Anishinābe moved seasonally, specific places in the region were particularly important. The falls on the Ottawa River where the city eventually emerged were known to Indigenous peoples as Asticou and were always sacred to the Anishinābe. Shamans and warriors engaged in spiritual practices (such as fasting and dreaming) made offerings to the powerful beings believed to dwell there.

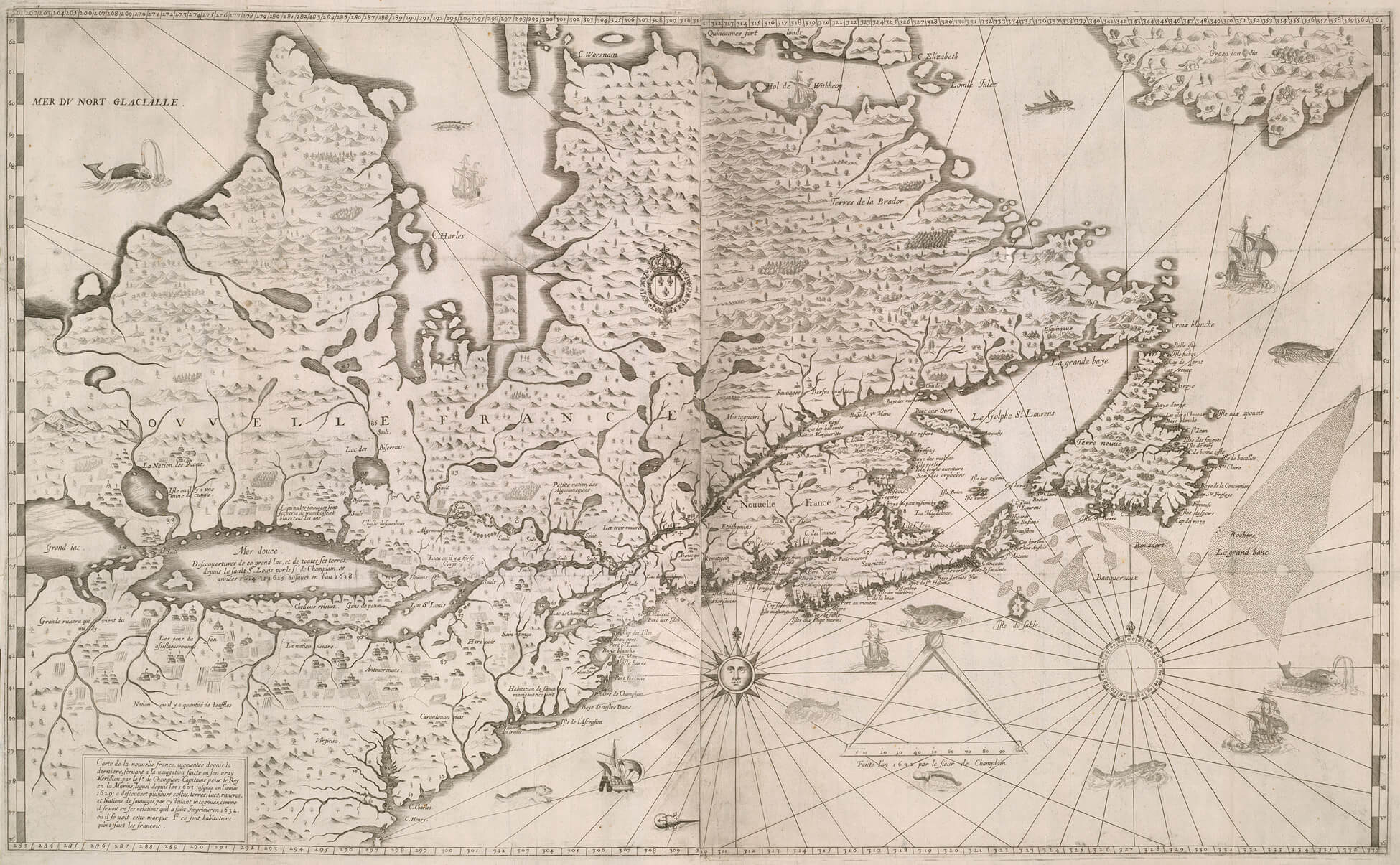

In 1613, Samuel de Champlain encountered the Algonquins in his journey up the Kichi Sibi, or “Great River.” Early contact had an immediate impact: French explorers renamed the falls the Chaudière, a name which is still in use, and Champlain published maps documenting his knowledge of the river. Although European settlement began in the Saint Lawrence River valley, Algonquins continued to inhabit the Ottawa valley. Today, their descendants carry on the cultural and artistic traditions of their ancestors, with the two largest First Nations being Pikwàkanagàn (Golden Lake, Ontario) and Kitigan Zibi (Maniwaki, Quebec).

1613–1763: The Beginnings of European Settlement

After his journey into the interior of North America in 1613, Samuel de Champlain renamed the Kichi Sibi as the Outaouais (Ottawa) River, a derivation of the Anishinābe word meaning “to trade.” The name is fitting, since Ottawa has been, and continues to be, a site of trade in thought and practice among peoples of different origins, languages, and religious beliefs.

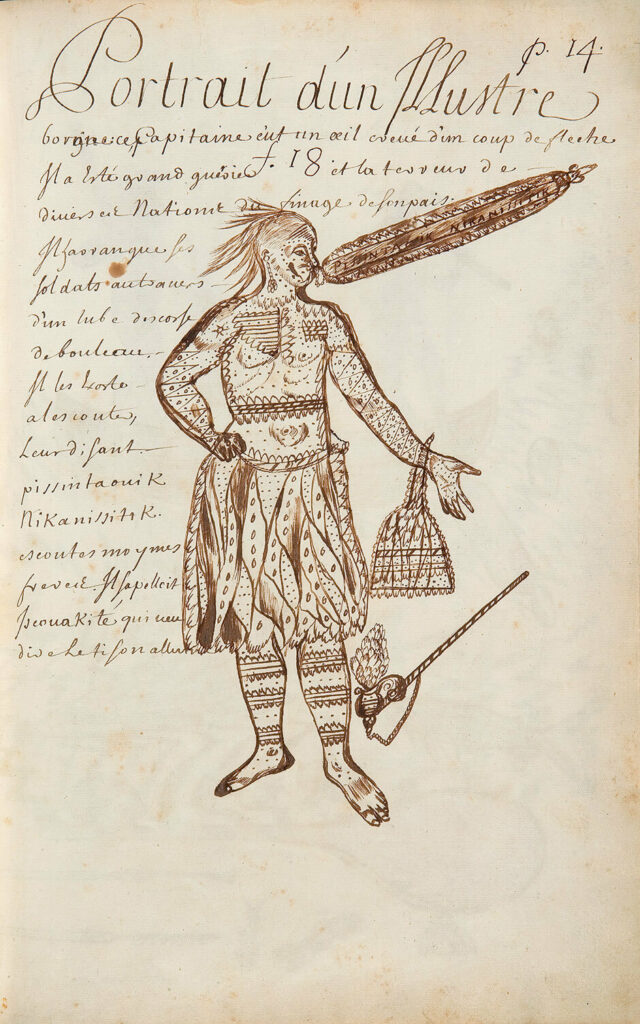

The era of French settlement in Canada, beginning in the early 1600s, had little impact on the Ottawa region. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, French fur traders and military expeditions used the great river to penetrate further into the continent. Priests also sought to convert Indigenous peoples to Christianity. No permanent settlement appeared in the seventeenth century, and few visual records of the Ottawa Valley exist. However, in 1632 Champlain published some highly stylized engravings in Paris, and one of them recorded four Algonquins whom he had met on Lake Huron. Champlain’s original drawings and maps have not survived. As such, the best-known visual depictions of French interactions with the First Nations are those created by the artist Louis Nicolas (1634–post-1700) between 1664 and 1675, such as Portrait of a Famous One-Eyed Man (Portrait d’un Illustre borgne), date unknown.

The Beaver Wars of the late seventeenth century, pitting the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy against the northern Algonquians and their French allies, severely restricted the scope of French settlement. The Great Peace of Montreal was signed between the two sides in 1701, at which point the French colony began to expand. The establishment of the Hudson’s Bay Company in England in 1670 for fur trading and its southern expansion toward the Great Lakes and the Ottawa River catchment area also had an impact on Indigenous trade patterns.

In the eighteenth century, settlers from Britain living on the Atlantic seaboard began to encroach on the lower Great Lakes and the Saint Lawrence River region. The French, in turn, built a series of forts to defend their territories. As European conflicts extended to North America, Indigenous peoples were drawn into them. The capture of New France in 1760 during the Seven Years’ War meant that Britain gained control over eastern North America. The Treaty of Paris of 1763 affirmed British sovereignty. While France ceded power, French-speaking settlers remained, continuing to farm, trade for furs, and practise their Catholic faith.

The conclusion of the war was also meaningful for Indigenous peoples. In the Royal Proclamation of 1763, George III established principles for the negotiation of future treaties with Indigenous peoples and declared all lands west of the Appalachian Mountains as theirs. Because it imposed limitations on settlement, the proclamation angered American colonists, becoming one of the causes of the American Revolution in 1775. In spite of wars, disease, and threats to their way of life, the Anishinābe peoples would continue to live in their ancestral territories, even as European settlement increased.

1763–1815: Postwar Settlement, Officialdom, and Souvenirs

The 1763 Treaty of Paris gave Britain unchallenged power in eastern North America. British military officers, trained in topographical representation, began to travel into the interior of the continent to map the land, garrison forts, and better understand the territory they now controlled. These officers administered the newly won colonies and worked with First Nations in the context of the Royal Proclamation of 1763. One such person was Royal Artillery officer Thomas Davies (c.1737–1812), who received art lessons as part of his training at the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich, England. This enabled him to draw dozens of sketches and topographical images that were highly accurate, effectively functioning as intelligence documents. Like other British officers, Davies was well connected to the English art world and aware of aesthetic theories and practices of the time.

After the American War of Independence (1775–83), Britain reinforced control over its colonies (including what later became known as Canada), assisted by an influx of United Empire Loyalists from the United States. In the following decades, many Americans also sought opportunities north of the border, especially in the Ottawa Valley. The Chaudière Falls, which offered commercial possibilities for mills to exploit the virgin forests of the Ottawa Valley, attracted New Englander Philemon Wright, who, with his family and five others, including one led by a free Black man named London Oxford, began to farm in the region from 1800 onwards. The settlement they created was known as Wright’s Town (today the city of Hull), and it grew rapidly. The vast majority of newcomers were white and anglophone, and the Black community remained relatively small until the 1880s.

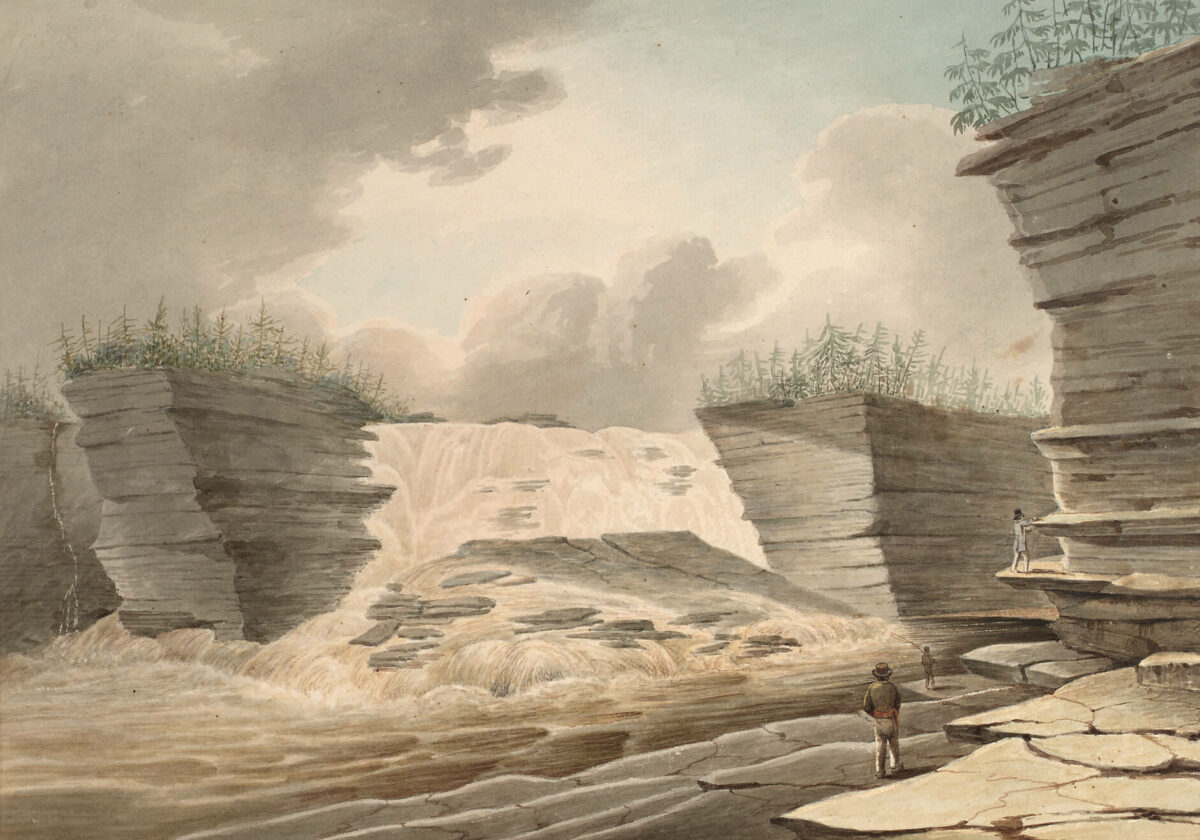

Colonial officials and their families also played a part in artistic endeavours in the region, collecting works by Indigenous artists, including clothing and objects such as basketry and quillwork, and creating their own pieces. While army engineers and surveyors made views for official purposes, many of their works were intended as souvenirs of stays in North America. The majority were watercolours—a portable medium popularized in England in the late eighteenth century. North American waterfalls inspired sensations of fear and fascination, and although Niagara Falls was the great wonder of the continent, other sites, including the Chaudière Falls, inspired artists well into the nineteenth century.

Before he left Canada in 1791, Davies painted View of the Great Falls on the Ottawa River, Lower Canada, 1791, a minute delineation of nature that includes an Indigenous group identifiable by their ear-loops as Anishinābe Ottawa or Ojibwe. Many colonial visitors would record the same scene over the next few decades. Their views at the Chaudière Falls invariably depict a wilderness in which the awesome power of the river is on full display, and the surrounding forests stretch off into seemingly limitless distances—but the land would soon change.

Determined to defeat France during the Napoleonic Wars, from the 1790s onwards, the British Navy blockaded Europe and was, in turn, cut off from continental supplies. This had a twofold effect on the Ottawa region. Britain needed to maintain its enormous fleet using timber, which from 1806 was supplied from the forests of the Ottawa Valley. The continental blockade impeded American ships, and the United States declared war on Britain in June 1812, resulting in the three-year conflict known as the War of 1812. The British government recognized the vulnerability of its Canadian colonies and of the Saint Lawrence water route during the war.

After the conclusion of peace in 1815, Britain strengthened its hold on the colonies by establishing military veterans and their families in the Ottawa Valley, in the mistaken belief that eighteenth-century treaties had extinguished Anishinābe claims to the territories. As well, the British government decided to build a canal from the Ottawa River to Lake Ontario via the Rideau River. Its construction would irrevocably change the Ottawa region and was fundamental to the growth of the future city.

1815–1854: Canal Building and the Establishment of Bytown

Lord Dalhousie, the Governor-in-Chief of British North America from 1820 to 1828, undertook a tour of Upper Canada in 1821, including a journey along the Ottawa River. His official draftsman, John Elliott Woolford (1778–1866), recorded several scenes at the Chaudière Falls. Aware of the area’s strategic importance, Dalhousie was particularly interested in the future site of the proposed Rideau Canal.

The canal’s construction was entrusted to Royal Engineer Colonel John By (1779–1836), who arrived in the region in 1826; a year later, the settlement that became Ottawa was named Bytown in his honour. By was also an artist, and a lithograph after a pencil sketch attributed to him shows the Chaudière Falls dwarfing the stick-like figures scrambling among the rugged rocks. The falls assert the power of nature, but human ingenuity would soon tame the river.

The First Nations, who had played a key role in maintaining British hegemony in Canada, were quickly being displaced. The Anishinābe attempted to protect their traditional lands in negotiations with the colonial government but succeeded only in obtaining tiny reserves, including at Kitigan Zibi in 1845 and at Pikwàkanagàn in 1873. Settlers from England, Scotland, and Ireland flooded in. Construction on a bridge across the Ottawa River to connect Upper and Lower Canada began in 1825. When the Rideau Canal opened in 1832, it provided a link to Kingston on Lake Ontario; moreover, this new route to Upper Canada and the Great Lakes ensured the military would no longer be reliant on the Saint Lawrence River.

The village of Bytown had become a centre for the lumber trade. Connected by steamboat to Montreal and Kingston, the canal route attracted British military artists and officials who travelled to see and record the landscape. By the early 1840s, Bytown was an integral part of the “Northern Tour,” a route broadly covering the passage from Quebec City to Niagara Falls via the Ottawa and Rideau Rivers, returning via the Saint Lawrence or by way of New York City.

Civilian surveyor-artists created works that are powerful statements of European notions of progress. A continuing focus of artistic interest was the Chaudière Falls, but many also depicted the canal, especially its locks and dams, since it was considered one of the world’s most impressive engineering feats. Watercolours by John Burrows (1789–1848) are among the most attractive official documents one might see anywhere: Bridges Erected Across the Ottawa River at the Chaudière Falls (Truss Bridge), after 1827, demonstrates a mastery of draftsmanship and perspective as well as an aesthetic approach beyond that of a straightforward engineering drawing, including the use of figures and a wagon to provide a sense of scale. The similarly named Thomas Burrowes (1796–1866) would record beautiful scenes along the canal, as well as settlements and farms in what is now eastern Ontario.

The work of officers from both the military garrison established on Barrack Hill and the few stationed in Bytown dominates this period of Ottawa’s art history. However, in contrast to other garrison towns like Halifax, Toronto, or Quebec City, the military establishment in Ottawa played no significant role in nurturing an artistic “scene” by organizing art exhibitions, commissioning works from local artists, or even producing printed views of the region.

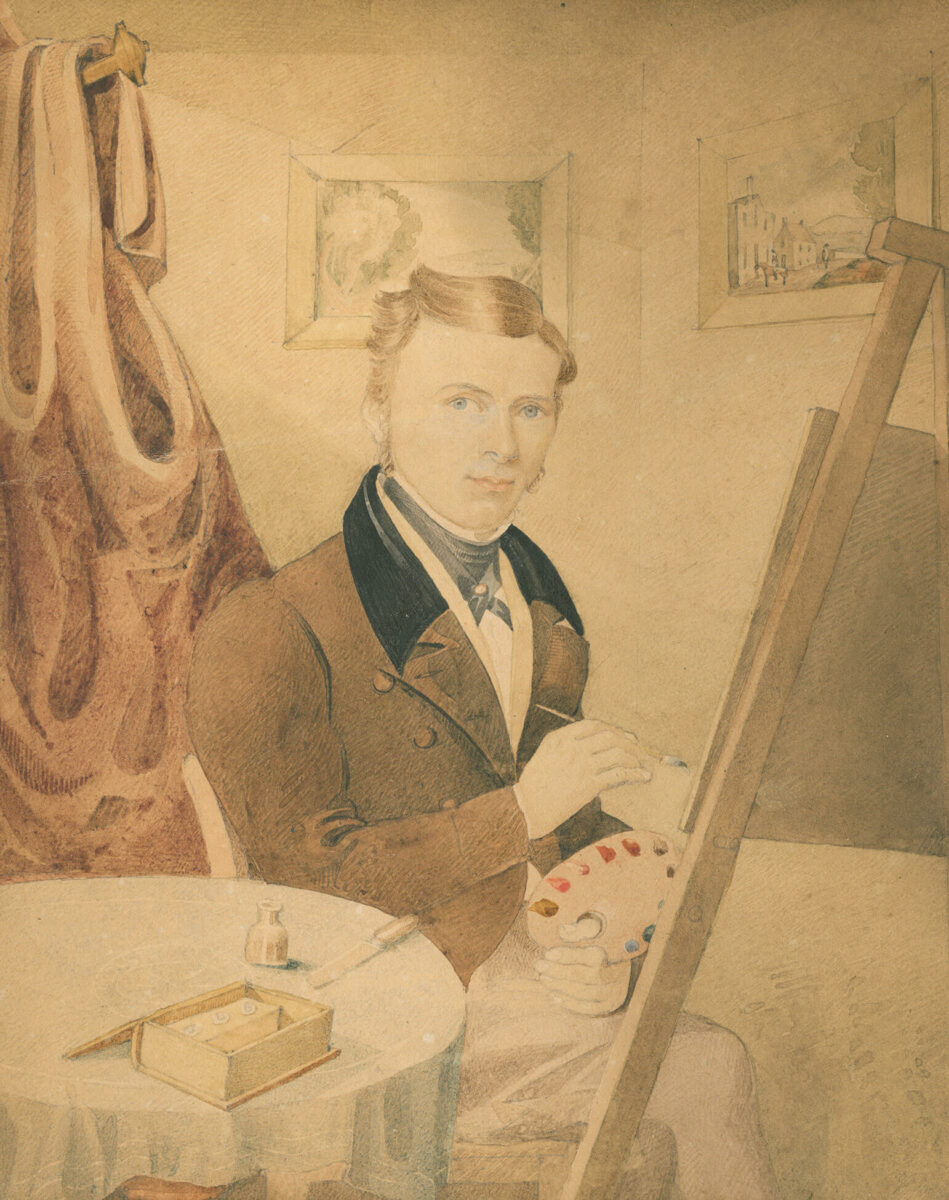

In the mid-1830s, Bytown had a population of 1,300, but by 1851 it had reached almost 7,000. Seeking marketable landscape subjects, professional artists from Montreal, Quebec City, and even the United States began to arrive, including Robert Bouchette (1805–1879) in the 1820s, Godfrey Frankenstein (1820–1873) in the 1840s, and Cornelius Krieghoff (1815–1872) in the 1850s. Other than the notable exceptions of Robert Auchmuty Sproule (1799–1845) and William S. Hunter Sr. (active 1836–1853), none of these artists played a part in the city’s cultural development. As early as 1836, Hunter had advertised in the Bytown Gazette as a painter and music teacher. Little is known of his work, but the 1853 art exhibition of the Bytown Mechanics’ Institute included six of his oil paintings of local scenery. Sproule, a miniature painter and drawing master, advertised an evening drawing class at his house in Upper Town in 1844 and offered to “produce good likenesses in Miniature.”

William S. Hunter’s son, William Stewart Hunter Jr. (1823–1894 ), also became an artist of note. By 1855 he had published Ottawa Scenery, which includes illustrations by both his father and himself. Photographers also settled in Bytown, offering competition to miniaturists, silhouette artists, and portrait painters, with a daguerreotypist arriving in March 1844. The first permanent photography studio was established in 1851 by Joseph Lockwood (1817–1859).

William S. Hunter Sr. had been the first of many people who offered to teach drawing and painting. Advertisements for other drawing classes and art schools appeared in Bytown newspapers throughout the period, many placed by female practitioners. For young women, when nineteenth-century social restraints limited prospects for employment outside of marriage, pursuits such as music, embroidery, and drawing were considered acceptable. Private academies supplied this training until the 1850s, and students likely participated in what seems to have been the town’s first public art exhibition, organized by Burrows in August 1846. Such exhibitions were then common throughout British North America and often provided the impetus for more serious artistic endeavours.

By the late 1840s, four distinct communities had emerged in Bytown: an “American community” (mostly businessmen in the lumber trade); a French Canadian mercantile class; a British landowning and mercantile class; and a working class made up of many Irish Catholic and French Catholic labourers and household servants. There is no evidence of Black domestic servitude in the mid-nineteenth century, nor of other visible minority communities.

Intellectual life had quickened with the foundation of the Mechanics’ Institute in 1847, which held its first exhibition in August 1853—artworks were among the variety of products displayed. The College of Bytown (now the University of Ottawa), founded in 1848, provided courses in linear and wash drawing. The town’s artistic scene had patrons, art schools, and organizations tailored to a certain class of white citizen, but Indigenous and working-class artisans engaged in other forms of artmaking such as beadwork and textiles, which were also recognized aspects of colonial artistic enterprise.

In 1841, the Province of Canada was formed with two components: Canada West (formerly Upper Canada) and Canada East (formerly Lower Canada). The provincial capital was not yet permanently fixed and moved from Kingston to Montreal to Toronto to Quebec City, back to Toronto, and again to Quebec City over the course of almost two decades. Meanwhile, Bytown was growing rapidly due to the strength of the lumber trade and increased settlement. It incorporated as a town in 1850, and within a few years it gained city status and changed its name to Ottawa.

1855–1880: Ottawa, a National Capital

In 1851, the opening of the Bytown and Prescott Railway created a new link from Ottawa to the outside world. With its growing population and position on the border between Canada East and Canada West, Ottawa harboured ambitions to become the permanent capital of the united Canadas. The success of its bid would determine the fate of the city.

In 1854, American artist Edwin Whitefield (1816–1892) arrived in Bytown, and he soon published two large lithographs: one with a view looking west from Barrack Hill up the Ottawa River, and the other looking east toward Lower Town and the Rideau Canal. These prints were a key element for Ottawa City Council’s 1857 memorial to the British Colonial Office in the competition to become the new capital. The bid was also accompanied by William S. Hunter Jr.’s Ottawa Scenery (1855), as well as a map prepared by engineer and artist William S. Austin (1829–1898). These visual documents may have helped persuade Queen Victoria to select Ottawa from a number of submissions.

Ottawa became the capital of the Province of Canada on December 31, 1857, and the capital of the wider Dominion of Canada on July 1, 1867. The impact on the city’s artistic development was significant. Ottawa was transformed from a remote lumber town into the political centre of a country that eventually spanned a continent. As historian John Taylor has noted, the dichotomy between Ottawa the city and Ottawa the capital arose almost immediately—a situation that persists today and pervades every sphere of city life, whether political, social, economic, or cultural.

Ottawa’s new status meant increased public support for painting, sculpture, and architecture; the influx of an educated and culturally aware group of senior public servants and viceregal representatives; and the arrival of artists seeking patronage, commissions, and buyers. By 1859 the city was changing, as construction began on the new Parliament Buildings designed by the Ottawa firms Stent & Laver and Fuller & Jones. A watercolour by Montreal artist James Duncan (1806–1881), who had visited the city on several occasions, depicted the Parliament Buildings from Nepean Point, which is still a favourite viewpoint for aspiring artists today. Alfred Worsley Holdstock (1820–1901), another Montreal-based painter, became the first of many to record not just the city but also its hinterland. His watercolours of the valleys of the Ottawa and Gatineau Rivers were highly popular.

The 1870s brought an influx of portraitists attracted by possible commissions, the best known being John Colin Forbes (1846–1925). The eccentric Delos Cline Bell executed an unusual allegorical composition that used Parliament Hill as a backdrop for a romantic celestial vision. Toronto artist Lucius Richard O’Brien (1832–1899) appears to have made annual sketching trips to Ottawa and vicinity in the mid-1870s. His watercolour Ottawa from the Rideau, 1873, a view from the banks of the Rideau River, is suffused with clarity and light. When the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts was established in 1880, O’Brien became its first president.

The civil service, which was transferred to Ottawa in the 1860s, included many individuals with artistic interests. W.H. Cotton (1817–1877), a member of the Governor General’s staff, was a competent watercolourist. Walter Chesterton (1845–1931), an English-born architect, painted many city views. His fellow architects John William Hurrell Watts (1850–1917) and Thomas Fuller (1823–1898) both played important roles in the city: Fuller, the designer of the Centre Block of Parliament, became the chief architect in the Department of Public Works, while Watts became Ottawa’s chief architect.

Photographer William J. Topley (1845–1930) returned to Ottawa from Montreal in 1868 to operate a branch of the Notman Photo Studio, eventually taking it over himself in 1872. Topley Studio would play a key role in city life until 1923. In the following decades, other photographers also established practices, including A.G. Pittaway (1858–1930), whose portrait of Paul Barber and his family is one of the earliest visual representations of Ottawa’s small Black community.

There were few opportunities for artistic exhibitions. James Wilson & Co. held art displays and occasional auctions of Ottawa views. Fine art and “Ladies Work” appeared in provincial agricultural society exhibitions, but there was nothing comparable to the Art Association of Montreal or the Toronto-based Ontario Society of Artists. Two Governors General, the Earl of Dufferin (in service 1872–78) and the Marquis of Lorne (in service 1878–83), who was married to Princess Louise, the daughter of Queen Victoria, were avid amateur artists and collectors and deeply interested in the arts, as were their wives.

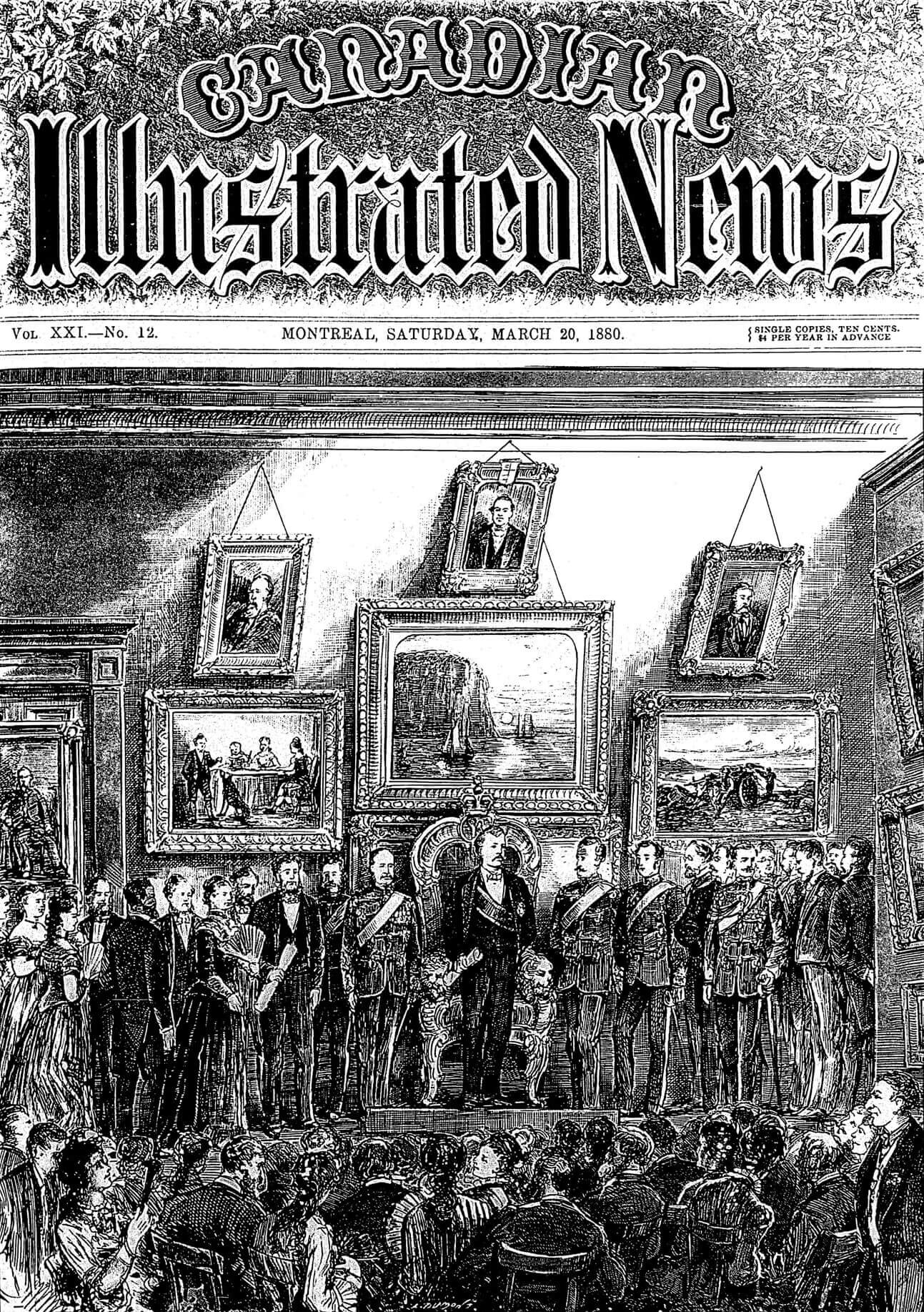

With viceregal encouragement, prominent Ottawa citizens met in May 1879 to discuss the foundation of the Art Association of Canada and a goal to encourage “knowledge and love of the fine arts, and their general advancement throughout the Dominion.” The first Grand Dominion Exhibition was held in Ottawa in September of that year, and artists from many parts of the country participated. Soon after, the Canadian Academy of Arts (the Royal being added in 1882) was created. Its first official exhibition opened in Ottawa on March 6, 1880, under the patronage of the Marquis of Lorne and the Princess Louise. The Royal Canadian Academy of Arts (RCA) also became responsible for the National Gallery of Canada and annual exhibitions held in Ottawa and other cities throughout the Dominion. Ottawa artists and architects were involved in the RCA from the beginning: Chesterton and Watts were among the first associates, while Fuller joined in 1882. Only one woman, Charlotte Schreiber (1834–1922) of Toronto, was a member.

Canada expanded its borders during this period. In 1870, Manitoba joined Confederation, followed by British Columbia in 1871 and Prince Edward Island in 1873. With the acquisition of Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory from the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1869, Canada stretched from sea to sea to sea. A series of treaties with First Nations peoples irrevocably changed their status within the new nation, and the influx of minority groups such as Chinese railway labourers and formerly enslaved people from the United States changed entire communities. Following the completion of a transcontinental rail network in 1885, Ottawa found itself at the heart of one of the largest countries on Earth.

1880–1914: The City Grows

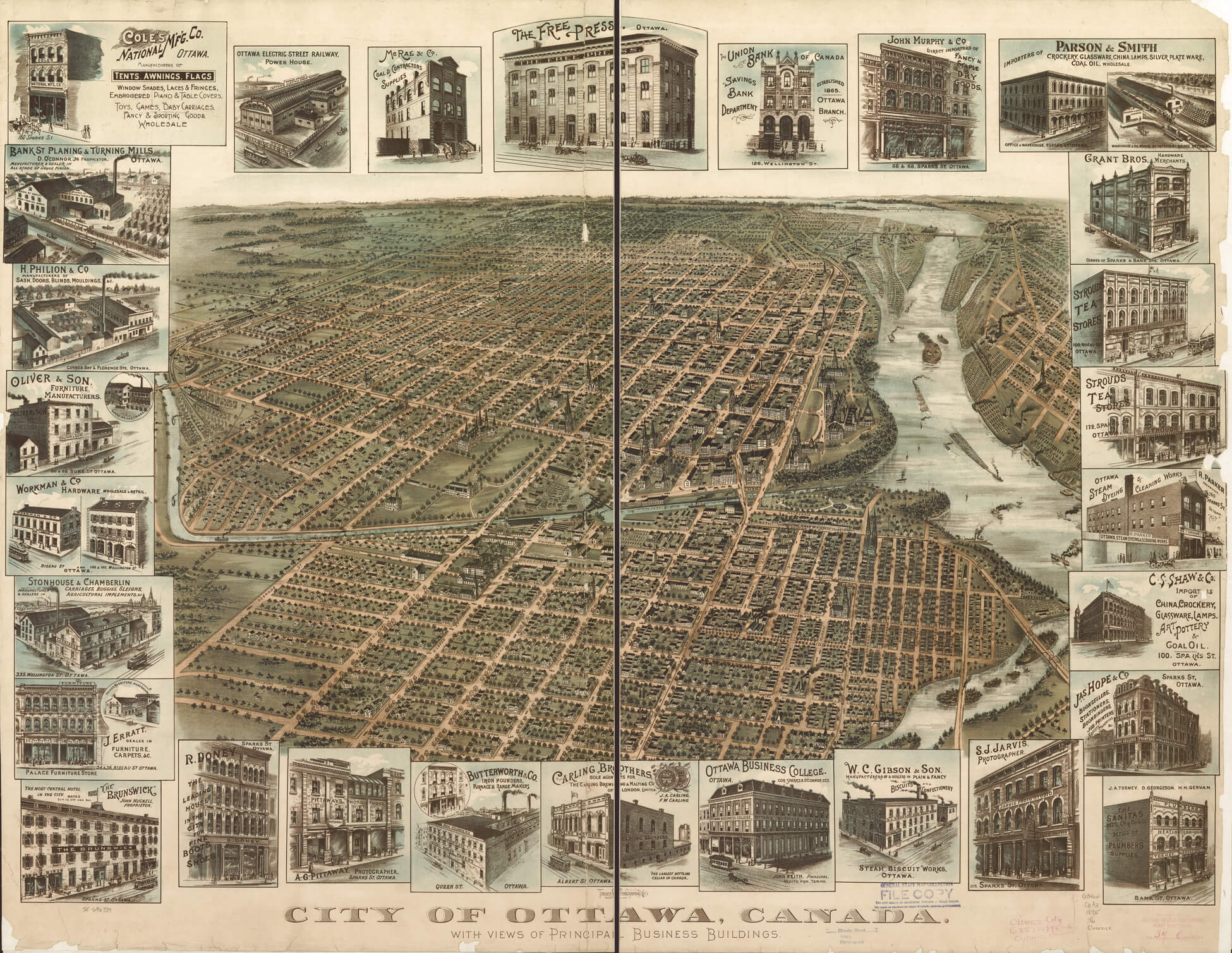

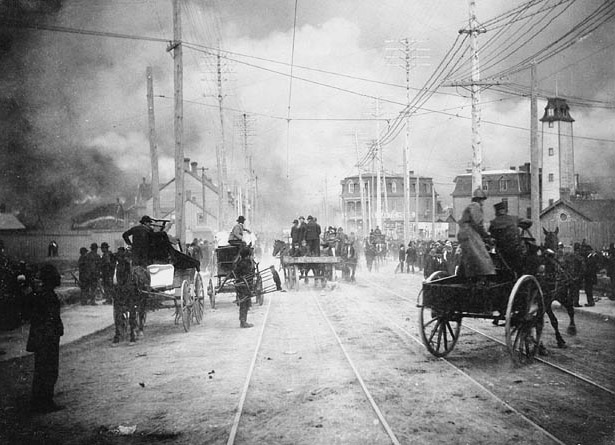

As Canada grew, Ottawa’s population tripled in thirty years, from 27,412 in 1881 to 87,062 by 1911. The city changed from an industrial centre largely dependent on lumbering into a city dominated by a federal public service. Economic growth was stalled by a worldwide depression in the 1890s and the disastrous Great Fire of 1900, but new railroad links, better municipal infrastructure, interprovincial bridges, an expanding civil service, and the growth of light industry offset these setbacks. The construction of Union Station and the Château Laurier hotel, both iconic buildings that survive to this day, transformed the urban centre. There continued to be an Anishinābe presence in the city and the Ottawa and Gatineau Valleys, while several new ethnic groups began to appear—the largest being German, with smaller communities of Jewish and Italian immigrants. A tiny Chinese population of about one hundred first appeared in the 1911 census, and the number of Black citizens was even smaller.

Spurred by the examples of Governors General Dufferin and Lorne, succeeding viceregal representatives were responsible for such cultural initiatives as the Women’s Art Association (formed in 1887), with an Ottawa branch opened in 1898, and the Women’s Canadian Historical Society, which was also founded in 1898. Though these groups did important work, they were problematic for Ottawa itself. The viceregal court at Rideau Hall and Ottawa’s position as the capital of a far-flung nation were more attractive to the well-to-do, diverting their energies from championing municipal improvements. Many community leaders saw greater prestige in developing national institutions with an impact throughout Canada rather than organizations that focused only on Ottawa.

Nevertheless, there were local initiatives. The Ottawa Art School opened in April 1880, part of the Fine Arts Association of Ottawa, which incorporated in 1883 as the Art Association of Ottawa. It was supported by the Marquis of Lorne and Princess Louise, and the association’s board of directors and executive committee included a mix of merchants, civil servants, collectors, and artists. The art school provided education to aspiring artists (male and female), and with modest admission fees, it was accessible to a wide range of citizens. In its early years, the school’s teachers included William Brymner (1855–1925), Frances Richards Rowley (1852–1934), Charles E. Moss (1860–1901), and Franklin Brownell (1857–1946). In the 1890s, the art school ran into financial difficulties, and the withdrawal of provincial funding in 1900 led to its closure. In its twenty years of existence, it trained many students who would go on to distinguish themselves in the fields of art, architecture, and design, including Werner E. Noffke (1878–1964), Marie-Marguerite Fréchette (1878–1964), and Ernest Fosbery (1874–1960).

Many artists still came to Ottawa in search of government and private patronage, the most prominent being John Colin Forbes and Andrew Dickson Patterson (1854–1930). Conversely, artists from the area, such as John Charles Pinhey (1860–1912) and Mary Bell (1864–1951), left to study elsewhere. Pinhey eventually moved to Montreal, and Bell, after marrying English artist Charles Herbert Eastlake (1867–1953) in 1895, resided in England. She only moved back to Canada in 1939.

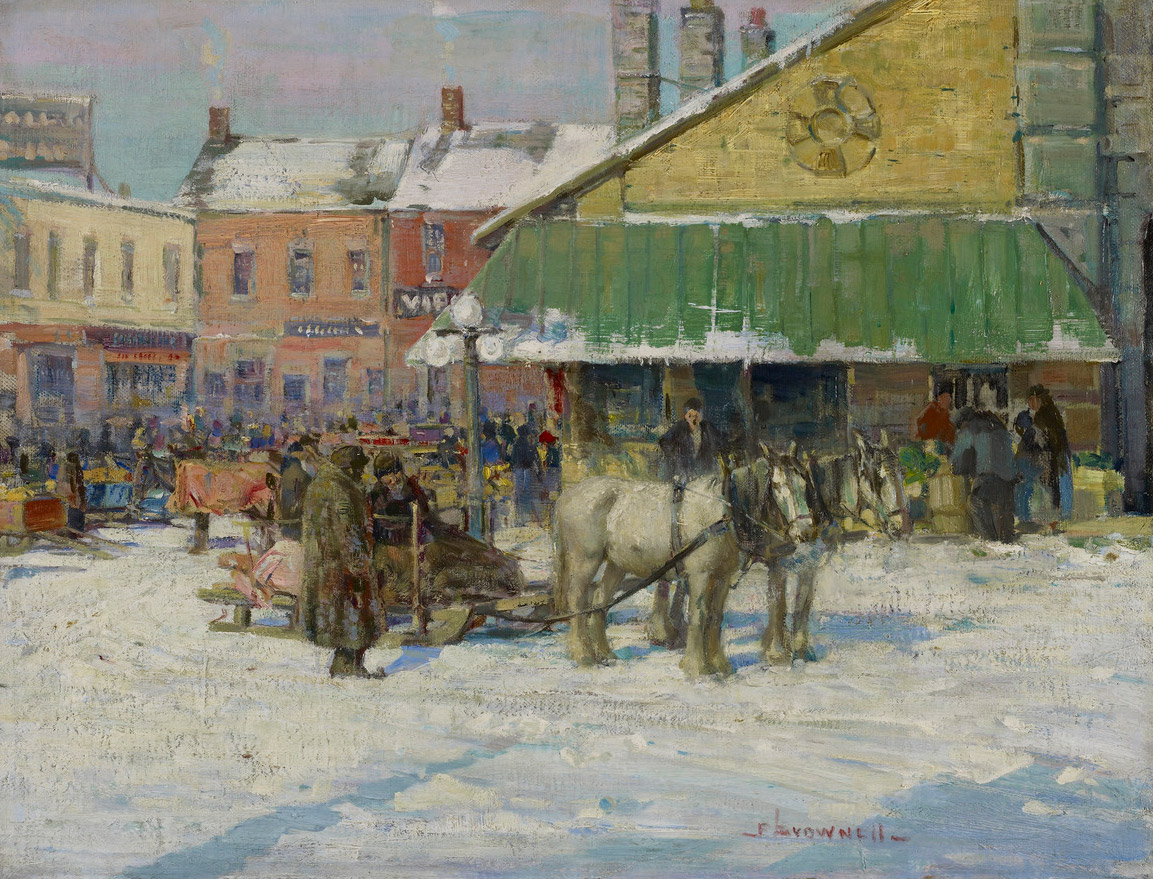

Although the absence of a larger commercial market hurt artistic prospects, an Ottawa art scene was established by the end of the nineteenth century. Brownell, Moss, and Harold Vickers (1851–1918) were assured of a small but supportive local art community, although the tastes of their patrons were attuned to traditional academic painting. James Wilson & Co. held annual exhibitions featuring the work of local artists and Ottawa Art School students, who were mostly drawn from the city’s anglophone and francophone communities. The Royal Canadian Academy of Arts also had exhibitions in Ottawa several times. Ottawa artists, including Brownell, Moss, John William Hurrell Watts, and Hamilton MacCarthy (1846–1939), a distinguished sculptor who moved to Ottawa in 1899, played important roles as members and leaders on the RCA council.

Founded in 1894, the Camera Club of Ottawa, and its successors, would foster significant experiments and activities in the Ottawa cultural scene over the next five decades, as did many commercial photography studios. Like the Literary and Historical Society and the Ottawa Field-Naturalists’ Club, it attracted a mixture of individuals from many backgrounds interested in exploring aspects of cultural life in an organized setting.

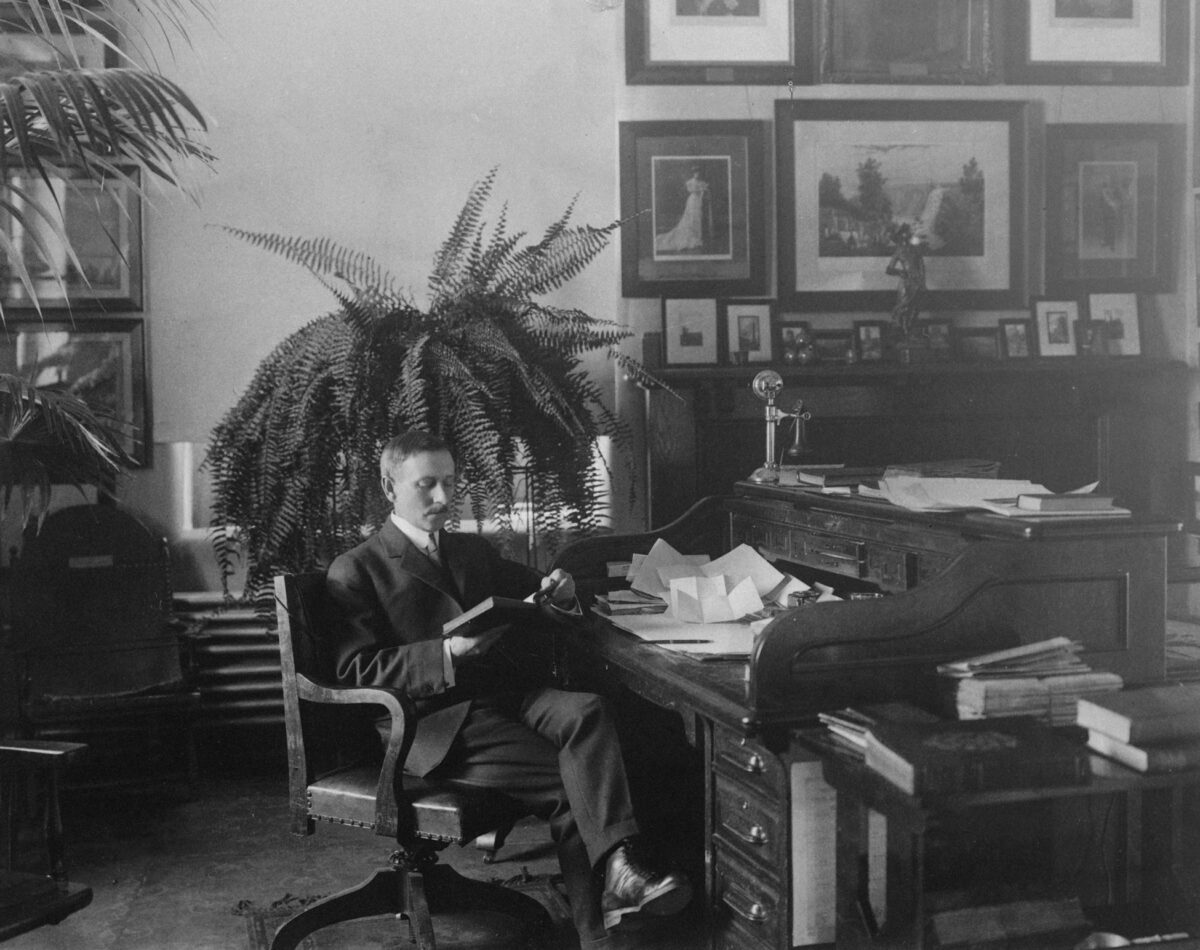

The opening in 1907 of the Public Archives of Canada’s new building on Sussex Drive was significant, as it became an important venue to see Canadian art. Dominion archivist Arthur Doughty was an enthusiastic arts supporter for decades, purchasing works by Brymner, Brownell, Watts, Henri Fabien (1878–1935), Henri Beau (1863–1949), and younger artists, including Graham Norwell (1901–1967) and Jobson Paradis (1871–1926). That same year, the federal government’s Arts Advisory Council severed ties between the National Gallery and the RCA, and recommended a new building for the gallery—it moved to the recently completed Victoria Memorial Museum in 1912. The first director, Eric Brown, would have an enormous influence on Canadian art over the next three decades. In 1910, the National Museum of Man (now the Canadian Museum of History), also installed in the Memorial Museum, launched an anthropology division, which began to acquire the work of Indigenous artists.

1914–1939: Winds of War and Times of Peace

The outbreak of the First World War was a defining moment for both Ottawa and the country. When Britain declared war on August 4, 1914, Canada, as part of the British Empire, was automatically engaged as well. The country eventually sent more than 600,000 troops overseas, while many others enlisted in the Royal Navy and Air Force. More than 67,000 Canadians and Newfoundlanders died, and another 170,000 were wounded. But the war also kindled Canada’s national aspirations, and the nation’s growing status was marked by its inclusion as a separate signatory to the Treaty of Versailles in 1919.

Ottawa’s population almost doubled in the interwar era, from 87,062 in 1911 to 154,951 in 1941, transforming the city’s shape and infrastructure. However, Canadians of British and French heritage still made up more than 90 per cent of the population. By 1939 the federal public service was the city’s largest single employer, and the Second World War would accelerate its growth.

The First World War also had an impact on local artists. Ernest Fosbery joined the Canadian Army, was wounded at the Somme, and played a key role in creating the Canadian War Memorials project. Born in Whitby, Ontario, artist Florence Helena McGillivray (1864–1938) returned from Europe, settled in Ottawa, and began to influence the work of Canadian artists who had not been abroad during the war. Franklin Brownell, who had made regular sketching trips to the West Indies and Lower Saint Lawrence, concentrated instead on painting scenes of the ByWard Market and the Gatineau River Valley.

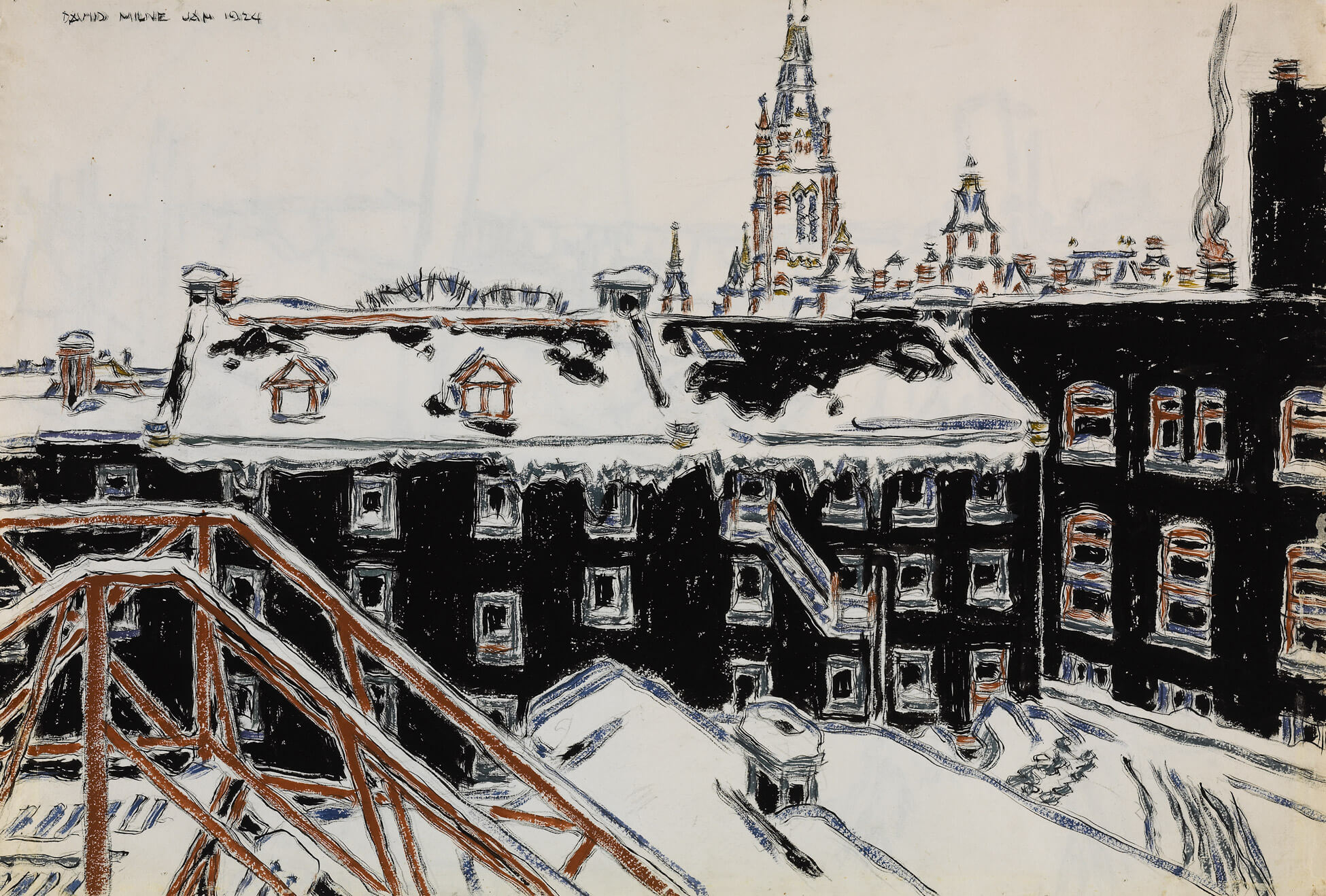

The postwar growth of the city and its public service would affect the artistic scene in several ways. While standard Canadian art histories of this period reveal few references to Ottawa (except to the National Gallery), many artists, including David Milne (1882–1953), Kathleen Moir Morris (1893–1986), Mabel May (1877–1971), and F.H. (Frederick) Varley (1881–1969), came to the city in search of patronage. In 1923, Milne hoped to find a job in the federal government and sell works to the National Gallery and other buyers. He noted in a letter to a friend: “Working for the government is the correct thing here, even artists work for the government…. Ordinarily they seem to have quite a bit of free time. They don’t know how lucky they are, it is practically a subsidy to art.” While Milne sold some pieces to the National Gallery, such as Old R.C.M.P. Barracks II, 1924, and made friends, he was unable to find employment. He left for New York in April 1924, not returning to Canada until 1929.

What Ottawa lacked, unlike Montreal and Toronto, was a robust and large-scale industrial economy that could contribute to artistic endeavour either through direct patronage or indirect support in the form of jobs. With the notable exception of the federal Exhibits and Publicity Bureau, founded in 1917, and small design sections within larger government departments, there were limited opportunities for commercial art, and few if any design and printing companies existed.

In spite of this, a lively artistic scene developed. The Art Association of Ottawa and Ottawa Art School were revived, providing a new impetus for professionals and students alike. A number of creative groups formed, including the Studio Club (1921) and Les Confrères artistes Le Caveau (1933). Many prominent artists were born and trained in Ottawa, contributing to the national scene while making Ottawa their permanent home. Brownell, McGillivray, Fosbery, Graham Norwell, Frank Hennessey (1894–1941), Harold Beament (1898–1984), Pegi Nicol MacLeod (1904–1949), Henri Masson (1907–1996), Wilfrid Flood (1904–1946), and Jean-Philippe Dallaire (1916–1965) are among the better-known artists who worked in Ottawa between 1914 and 1939—and many of them created modern paintings of the city and surrounding area, such as Flood’s Approach to Hull, 1937. Madge Macbeth and Newton MacTavish were well-known art critics.

Many local artists took part in the activities of the National Gallery and the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts as well as the Canadian Art Club, the Canadian Society of Painters in Water Colour, and the Canadian Group of Painters. In the field of artistic photography, a particularly gifted group of practitioners, including Johan Helders (1888–1956), Harold F. Kells (1904–1986), Charles E. Saunders (1867–1937), Clifford M. Johnston (1896–1951), and Yousuf Karsh (1908–2002) made Ottawa a centre for international salon photography.

One key moment for the city’s artistic scene was the landmark Women’s Art Association exhibition in 1921. The energy and connections that came out of this show led to the growth of other organizations. The Ottawa Art Club, formed in January 1921, held weekly meetings for members to discuss art and critique each other’s work. The club’s fall exhibitions included the work of such artists as Moir Morris, in Ottawa from 1922 until 1929; Nicol MacLeod; Emily M.B. Warren (1869–1956); and Norwell. Another member was artist Lysle Courtenay (b.1900, active until 1937), whose art gallery gave Goodridge Roberts (1904–1974) a solo exhibition in 1930 and Nicol MacLeod her first in 1931. The Studio Club’s membership formed the core of the “Ottawa Group” that exhibited at the University of Toronto’s Hart House in January 1924—Paul Alfred (1892–1959), Beament, Hennessey, McGillivray, Norwell, Milne, and visiting Japanese printmaker Yoshida Sekido (1894–1965) were among the artists represented. The club’s members were also part of Canada’s contingent at the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley Park, England, later in 1924, which showcased works by Alfred, Norwell, Hennessey, Milne, and Morris.

Another significant organization was Les Confrères artistes Le Caveau, founded by Father Gaudreault, a Dominican monk, in 1933. It included an art school whose principal teachers were Masson and Flood. The group also held annual exhibitions until 1941; the 1938 catalogue listed contributions by Flood, Masson, Jack Nichols (1921–2009), Gordon Stranks (1913–1993), Tom Wood (1913–1997), Gladys Pike, and artists from the French Embassy. As well, Stranks and Harry Kelman co-founded Contempo Studios, which organized a show for Roberts in 1941 and offered evening art classes.

Many artists worked or began their careers in Ottawa during the interwar period. Varley, who was in the city intermittently from 1936 to 1943, complained that it was a “Christian Scientist” town, and his pupils “dilettantes.” Varley came at the wrong time—with the Depression, federal budgets were slashed, jobs dried up, and few people had money to spend on buying art. Still, he did get hired to record a trip on the Eastern Arctic patrol ship Nascopie, and he carried out work for the Department of Agriculture. He was also commissioned to execute a portrait of H.S. Southam, who sat on the National Gallery’s board of trustees.

To make a living, Roberts opened a summer art school in Wakefield, north of the city on the Gatineau River, in 1930. He barely scraped by during his three-year stay, although he received encouragement from local supporters. In 1932, Roberts had a breakthrough exhibition in Montreal, and in November 1933 he became a resident artist at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario. By 1936 he had moved back to Montreal. Little is made of Roberts’s temporary interregnum in Ottawa, but his artistic career took off during those years.

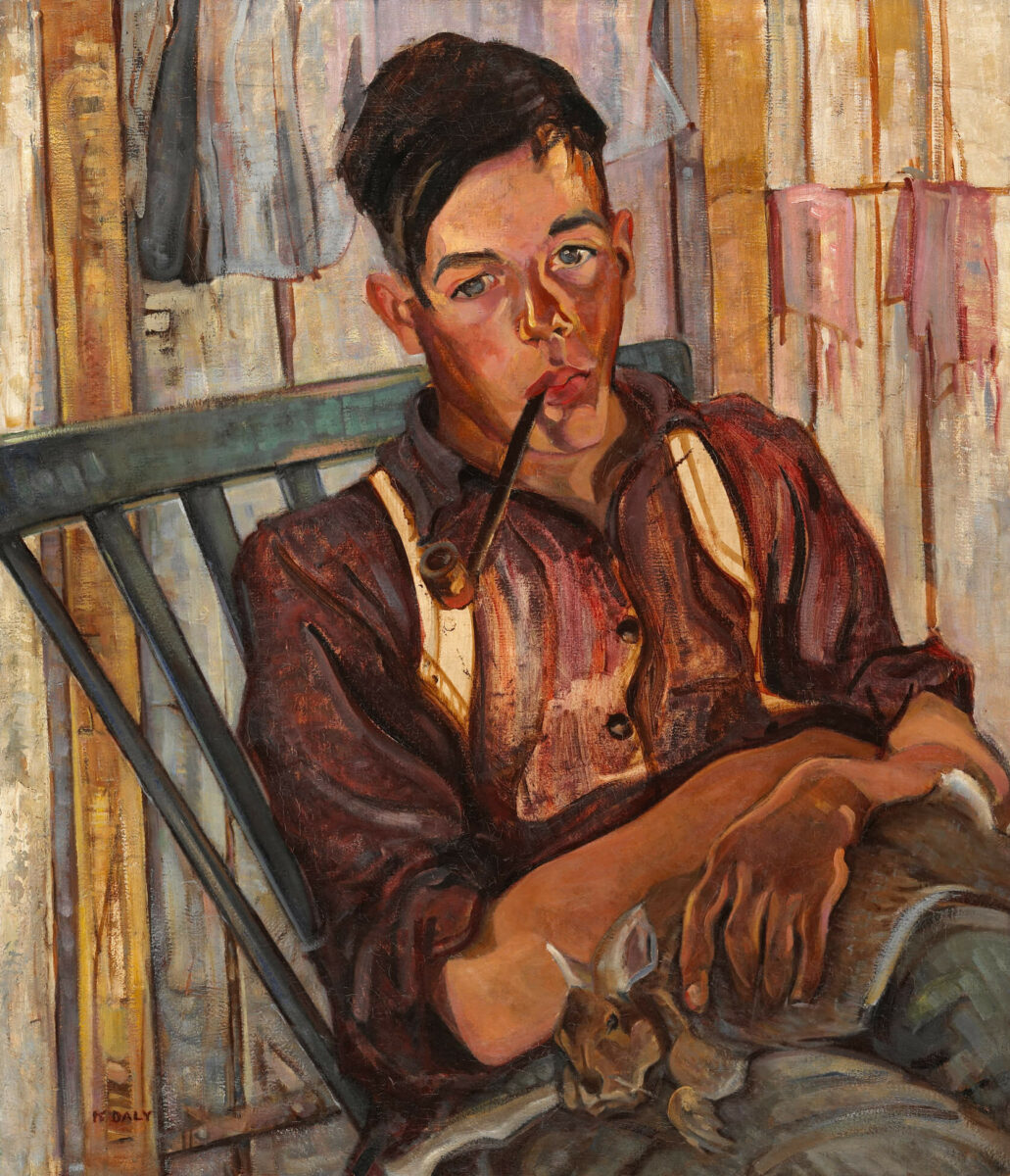

The decades of the 1920s and 1930s saw continuous development in the fine arts in Ottawa, centring on several resident artists, the most prominent being Brownell and Fosbery. Yet at the same time, there were artists who left the city, such as Kathleen Daly Pepper (1898–1994) and George Pepper (1903–1962), who moved to Toronto. Many long-time arts supporters passed away, including photographer William J. Topley in 1930, art dealer James Wilson in 1932, Dominion archivist Arthur Doughty in 1937, and National Gallery director Eric Brown in 1939. Talented younger artists began to emerge, while others came to Ottawa hoping to improve their position in the capital’s art world. National institutions provided some local benefits, but they also hindered efforts to create a more dynamic art scene. No civic gallery appeared, nor was the rich history of regional artistic achievement documented. It would take four more decades before the situation would change.

1939–1950: The Second World War and the Emergence of a New Art Community

The declaration of war on Germany on September 10, 1939, brought enormous changes to Ottawa. Almost overnight, the machinery of a nation at war needed to be coordinated by a vastly expanded bureaucracy. “Temporary” buildings were erected throughout the city, an influx of workers crowded living quarters, and the population grew to over 200,000, aided in part by the annexation of large portions of neighbouring townships. By 1945 the public service employed 34,740 people, and it had become a more professionalized and well-educated organization, led by leaders who had studied abroad and practised a deeply felt sense of Canadian identity.

In 1940, “frivolous” activities, such as the classes of the Art Association of Ottawa and the international photographic salons at the National Gallery, were suspended. But the creation of the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) in 1939 attracted a new generation of talented artists to the capital, including Ralph Foster, Albert Cloutier (1902–1965), Laurence Hyde (1914–1987), and Art Price (1918–2008). The NFB would prove to be a bright spot in artistic life during the dark war years.

The National Gallery continued to share an inadequate space in the Victoria Memorial Museum with the Museum of Man, and it had an insignificant acquisition budget. Nevertheless, it played an important role in the war effort, leading the Canadian War Art Program, which employed Canadian artists (including several from Ottawa) to record the war at home and abroad. The National Gallery also sponsored the Sampson-Matthews silkscreen print program, launched in 1942, which saw the distribution of reproductions of Canadian paintings for display at armed forces bases and administrative offices around the world as a reminder of what they were fighting for.

Many younger artists joined the armed forces, including Charles Anthony Law (1916–1996), Robert Hyndman (1915–2009), Tom Wood, and Paul Alfred. Hyndman, Goodridge Roberts, and Ottawa-born Alan Beddoe (1893–1975) became official war artists, while Pegi Nicol MacLeod, Wood, and Law would contribute on an unofficial basis. Hull-born Jean-Philippe Dallaire, who had studied art with Le Caveau, went to study in France in 1939 but was interned as an enemy alien by the Germans in 1940.

Some artists worked in government offices, while others, like Henri Masson, continued to teach and paint. The Federation of Canadian Artists (FCA) was established in 1941, with an Ottawa branch created in 1945. Masson was president, Wilfrid Flood was a committee member, and Laurence Hyde was vice-president. Hyde had arrived in Ottawa to work for the NFB under John Grierson (1898–1972) in 1941, as had Harry Mayerovitch (1910–2004), Hubert Rogers (1898–1982), Norman McLaren (1914–1987), and Alma Duncan (1917–2004). Flood’s death in 1946 meant the end of the local FCA branch, but many Ottawa artists continued to belong to the national organization.

In 1944, the House of Commons Special Committee on Reconstruction and Re-Establishment called for culture to be included in postwar planning. The Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, then led by Ottawa artist Ernest Fosbery, was among the organizations advocating for such inclusion. This would lead to the 1949 Royal Commission on National Development in the Arts, Letters and Sciences, popularly known as the Massey Commission.

In 1943, Walter Abell moved to Ottawa from Wolfville, Nova Scotia, to take on the position of director of education at the National Gallery of Canada. He brought with him Maritime Art magazine, founded in 1940. With his move, the magazine was renamed Canadian Art—a title signalling the intention to embrace a broader view. He encouraged other National Gallery staff to contribute, with pieces by Kathleen Fenwick, Robert Hubbard, and Donald Buchanan gracing future issues.

Many veteran war artists returned to the city at the end of the war. Hyndman took on various mural and portrait commissions, and later he began a long career as a teacher at the Ottawa School of Art. Wood’s job with the Canadian Government Exhibition Commission enabled him to hire many younger artists to work on projects. Ralph Burton (1905–1983) befriended A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974) after the latter’s move to Manotick outside the city in 1955, and he became known for his local street scenes, such as Salvation Army Depot Lloyd Street, 1963–64, and views of eastern Ontario and western Quebec. In the postwar period, Ottawa’s art scene flourished, and in succeeding decades it became not a place to come from but a place to be. Changes were coming to both Ottawa and the country as a whole, as governments began to utilize the power of art to build Canadian society.

1950–1988: Coming to Maturity

From the 1950s onwards, Ottawa grew into a nationally significant centre of artistic expression. Developments over this period continued to reflect the problematic nature of the city’s creative fabric—artists relied on government jobs to support themselves, talented individuals sought opportunities elsewhere, national concerns outweighed local ones, and patronage continued to be very conservative—but an era with different expectations arose. Artists took greater control of their own careers within a framework of new schools, galleries, and organizations. By 1988, a fully supported and publicly funded municipal art gallery would be established, as would a major artist-run centre.

In the years after 1945, Ottawa witnessed the arrival of new immigrant communities and talented individuals from around the globe. At the same time, work by First Nations, Inuit, and Métis artists began to be appreciated, and this contributed significantly to changing ideas about the role of art. Long-time practitioners of traditional crafts, such as Sarah Lavalley (1895–1991) of Pikwàkanagàn, kept Indigenous worldviews alive, and others, including Ron Noganosh (1949–2017) and Gerald McMaster (b.1953), experimented with new media while telling Indigenous stories, as can be seen in McMaster’s painting Conversation With…, 1988. Even though some Ottawans regretted the loss of a small-town feeling, the city of the 1980s was a more exciting and energizing place to live than it was in the 1940s. The population grew to over 675,000 by 1991—a substantial increase in four decades.

The establishment of new post-secondary institutions—Carleton University, founded in 1942, and Algonquin College, the successor to the Eastern Ontario Institute of Technology, created in 1965—and the evolution of the University of Ottawa into a secular, bilingual institution also transformed intellectual life. The relocation of the National Film Board to Montreal in 1956, with the exception of the Still Photo Division, was a real loss.

In Canada as a whole, the introduction of modernism and Abstract Expressionism in art is well known, but these movements also had their champions in Ottawa. A preoccupation with the Canadian landscape continued, but some artists also focused on the urban environment, including Gordon Stranks and Ralph Burton. The beginning of the 1950s saw several important initiatives. John Robertson left a job at the National Gallery of Canada in 1953 to found Robertson Galleries, which featured younger artists including Takao Tanabe (b.1926), Eva Landori (1912–1987), and Gerald Trottier (1925–2004). Robertson was determined to showcase contemporary movements, and these artists were highly innovative—Tanabe, for instance, was experimenting with abstraction in works such as Interior Arrangement with Red Hills, 1957. As well, Robertson helped revive the Ottawa Art Association in 1951, and two years later he became the first director for the new Municipal Art Centre (MAC). He hired such individuals as James Boyd (1928–2002), David Partridge (1919–2006), and Duncan de Kergommeaux (b.1927) to teach at the MAC, which became an important gathering place for local artists.

Artists among the new immigrants to the city included Hungarian-born sculptor Victor Tolgesy (1928–1980), American Frank Penn, and Dutch-born Theo Lubbers (1921–2013), who together would form the Guild Studio for Contemporary Liturgical Art, along with Trottier. They shared a common interest in religious expression through art, which was rewarded in the construction of numerous modern churches to serve a postwar population boom. Juan Geuer (1917–2009), another Dutch-born immigrant, would have a huge impact as well.

Younger Ottawa-born artists also emerged to make their mark. In January 1950, Kenneth Lochhead (1926–2006) introduced studio courses in painting and drawing at Carleton University before leaving to take up the same position at Regina College, only to return in the 1970s. Trottier studied in New York and Europe before coming back. Boyd also went to New York, but by the mid-1950s he was an active member of the city’s artistic scene. Robert Rosewarne (1925–1974), who had studied under Mabel May and Lionel Fosbery (1879–1956), worked for the federal government from 1951 onwards, and with his wife, Fran Jones, he led the local printmaking scene, creating works such as 5 O’Clock #3/5, 1959.

Post-secondary institutions in Ottawa began to play a much larger role in the city’s art scene. In 1943, Carleton University launched a program in the history of art and introduced studio classes. Trottier taught art at the University of Ottawa in the mid-1960s, after it established a fine arts program that developed into one of the most innovative in the country. The program eventually employed Lochhead, Leslie Reid (b.1947), Evergon (b.1946), Michael Schreier (b.1949), and Lynne Cohen (1944–2014). Ottawa-born Richard Gorman (1935–2010) returned from Toronto to teach painting and drawing at the Ottawa School of Art and the University of Ottawa.

Ottawa’s most famous artist in this period was photographer Yousuf Karsh. His 1941 portrait of Winston Churchill had brought him worldwide fame. Karsh’s success in taking photographs of internationally known figures drew attention to the city and enabled his brother Malak Karsh (1915–2001) and other Ottawa-based photographers to build significant careers as well.

The move to Ottawa of such artists as de Kergommeaux, Partridge, Pat Durr (b.1939), Jerry Grey (b.1940), and Brodie Shearer (1911–2004), and the return of Trottier and Boyd, generated a critical mass for cultural evolution in the city. Some, like Geuer, continued to depend on full-time jobs in the federal government. Others taught with organizations such as the Civil Service Recreation Association Art Club or MAC, where Durr, Shearer, and Alma Duncan taught. By the late 1960s, the Municipal Art Centre had outgrown its aging quarters, and in 1977 it was rechristened as the Ottawa School of Art (OSA) in order to link to a historic past. The OSA then moved to its present quarters in the ByWard Market, where it continues to play a significant role in the life of the city.

While Robertson Galleries was the most notable commercial space, Le Foyer de l’Art et du Livre fostered a strong thread of cross-connections, particularly with the Montreal scene, as artists such as Jean-Philippe Dallaire and Henri Masson exhibited and worked in both cities. Other new galleries introduced younger artists and contemporary art to a wider public. Blue Barn Gallery opened in 1962 and operated until 1967; Lofthouse Gallery, Blue Barn’s downtown successor, opened in 1967; and Wells Gallery opened in May 1965. All three featured Toronto and Montreal artists such as Léon Bellefleur (1910–2007), Harold Town (1924–1990), and Aba Bayefsky (1923–2001) alongside local figures. A significant development was the increased visibility of the work of Inuit artists such as Kananginak Pootoogook (1935–2010), Pitseolak Ashoona (c.1904–1983), and Kenojuak Ashevak (1927–2013), who had been encouraged by federal bureaucrat and artist James Houston. Their art was exhibited and sold by Robertson Galleries from the late 1950s onwards. The Robertsons also formed a large personal collection of Inuit art—Contest of Strength, 1955, was one of the earlier works they acquired.

The demand for artistic training in the fields of design and applied art resulted in the emergence of two new programs in the 1970s: one at Algonquin College in Ottawa and another at the CEGEP (Collège d’enseignement général et professionnel), a general and vocational college, in Hull, Quebec. The development of one of Canada’s first artist-run spaces, the Sussex Annex Works, in 1973, which evolved into SAW Gallery, was another key moment. SAW was a pioneer for a distinctly Canadian system of artist-run centres that have helped democratize art in cities throughout the country, bypassing the big institutions and bringing artists to the forefront as leaders.

While there were more private collectors and arts-minded citizens than ever during this time, it was difficult to see the work of Ottawa artists in a public institution. In 1969, Tolgesy led a famous protest against the National Gallery for its failure to show the work of local artists. In the gallery’s defence, director Jean Sutherland Boggs admitted the truth of this, but she also stated, “Our parish is the entire country, and as a result we’re not here to support local talent… But we don’t discriminate…. We do have works by local people in our collection.”

The community finally took matters into its own hands, organizing the Visual Arts Ottawa Survey Exhibition No. 1 at Lansdowne Park in June 1975, which included more than 300 works by 156 artists from the Ottawa area. Critic Walter Herbert wrote the following in his introductory essay to the exhibition catalogue: “In 1967… When the municipal art centres and galleries of Vancouver and London and Yarmouth and Pointe Claire and Calgary and Levis and Kitchener and Brandon exhibited the works of their regional artists with great pride the Ottawa Valley was sadly invisible. Except for the National Gallery and, as the Prince of Denmark said, there’s the rub.” At the time, collecting in Ottawa was dominated by federal government economist O.J. Firestone, but members of the Edwards, Southam, Torontow, Loeb, and Teron families also built substantial collections that included works by regional artists.

In 1972, the Firestone Collection of Canadian Art, which was pan-Canadian in scope and importance, became accessible to the public after its donation to the Ontario Heritage Foundation. At the time there was no municipal body capable of accepting it. This situation spurred people to action. By 1985, the Ottawa Arts Centre Foundation (formed in 1984) had begun considering the possibility of transforming the old Carleton County Courthouse into a major arts centre. The city established a Visual Arts Office and a municipal art acquisition fund in 1985, as well as a percent-for-art program for all new municipal buildings. In 1988, the Gallery at Arts Court was finally established in the courthouse, more than a century after it had initially been proposed. With the opening of a new National Gallery building the same year, the fine arts in Ottawa entered a new era.

1989–2018: New Directions, New Perspectives

Ottawa in the 1980s offered people opportunities for growth. The federal public service remained the city’s biggest employer, growing from 217,000 in 1986 to 283,000 in 2010. The high-tech sector was increasingly important—new companies formed the core of what came to be called “Silicon Valley North.” In 2001, the old regional government of Ottawa-Carleton was replaced by a larger single municipality. Ottawa amalgamated with the surrounding cities of Nepean, Gloucester, Cumberland, Vanier, and Kanata, as well as the village of Rockcliffe and four outlying townships, to create the largest city in terms of physical area in Canada.

The overall population of Ottawa and its sister communities in 1986 was 606,636; by 2018 it was almost a million, with nearly 340,000 more living on the Quebec side of the river. In 2018 and 2019, Ottawa was the second-fastest growing city in Canada, and economic opportunity attracted a more diverse citizenry. By 2011, almost 24 per cent of Ottawa’s inhabitants were visible minorities, including substantial East and South Asian and Black communities, while 2 per cent were First Nations, Métis, or Inuit.

For the arts, population growth and a new economic engine meant more funding as well as patronage. The Gallery at Arts Court, under new director Mayo Graham, could count on the support of such activist artists as Pat Durr, Jerry Grey, Alex Wyse (b.1938), and Jennifer Dickson (b.1936). Exhibition spaces were renovated in 1991, and the renamed Ottawa Art Gallery (OAG) was officially designated as the city’s municipal gallery in 1992. The Firestone Collection of Canadian Art became the centrepiece of the new exhibition spaces when they opened.

Taking over as director in 1993, Mela Constantinidi led the gallery for seventeen years, during which time innumerable exhibitions of contemporary art featured an increasingly diverse community, with such artists as Dennis Tourbin (1946–1998), Eliza Griffiths (b.1965), Penny McCann (b.1960), Jeff Thomas (b.1956), Jinny Yu (b.1976), and Annie Pootoogook (1969–2016) achieving national and international attention. The history of Ottawa’s artistic legacy was also celebrated in a series of three survey exhibitions held in 1993, 1994, and 1995. An acclaimed new building opened in April 2018, largely due to the exertions of director Alexandra Badzak. With the establishment of the Carleton University Art Gallery (CUAG) in 1992, under the dynamic Michael Bell, there existed two institutions capable of hosting major exhibitions.

The Ottawa artistic community has flourished. Twenty-five organizations, including the artist-run SAW Gallery, the Canadian Film Institute, the Ottawa Arts Council, the Ottawa International Animation Festival, and the Ottawa Fringe Festival, all share space in the old courthouse. Other organizations are located throughout the region: Enriched Bread Artists, for example, formed in 1992 by Laura Margita and graduates of the University of Ottawa fine arts program, is a cooperatively run studio that has acted as both an art studio and an artistic laboratory. Gallery 101, Axenéo7, Daïmôn, and Central Art Garage are all important commercial galleries. Others, including Wall Space Gallery (2004) and Cube Gallery (2005), joined established venues such as St-Laurent + Hill, Galerie d’Art Vincent, Wallacks, and the OAG’s art sales and rental program to offer more outlets for artists to sell their work.

Ottawa’s active photographic community has also gained recognition from the city itself. In 2003, the city created the Karsh Award for professional photo- or lens-based artists, in acknowledgement of the immense contribution of Yousuf and Malak Karsh to the city’s cultural heritage. The award, which includes a monetary prize, has been won by Lorraine Gilbert (b.1955), Justin Wonnacott (b.1950), and Jeff Thomas, among others. Ottawa also created another exhibition space, the Karsh-Masson Gallery, which has shown the work of established and aspiring artists. In 2005 the School of the Photographic Arts of Ottawa opened, offering collaborative learning experiences and strengthening the city’s camera arts community.

During the 1990s and beyond, Ottawa developed a strong and rich contemporary Indigenous art community, including such practitioners as Joi T. Arcand (b.1982), Barry Ace (b.1958), Simon Brascoupé (b.1948), Rosalie Favell (b.1958), Meryl McMaster (b.1988), Frank Shebageget (b.1972), and Leo Yerxa (b.1947), to name a few. There has also been an explosion of interest in multimedia and performance art, and in exploring subjects of gender and sexuality, geographical space, and technology. The twenty-first century has seen a wide range of artistic threads being woven into new and extraordinary works.

None of this would have been possible without the support of collectors and community leaders, who rightly deserve recognition for their efforts. The new Ottawa Art Gallery building, the existence of the Carleton University Art Gallery, a mature artistic community, and imaginative and risk-taking curators and arts administrators have enabled Ottawa to take its rightful place as a centre of artistic excellence. From a rough and tumble lumber town, Ottawa has become a vibrant metropolitan centre. The arts no longer languish in the shadows of the National Gallery. The city’s artists, curators, dealers, and collectors have responded with creativity, energy, and unique approaches to the business of making art.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements