In the history of Ottawa’s artistic community, many individuals have led key initiatives that ultimately changed the city. Community builders included civic, business, and religious leaders, educators, social activists, and cultural entrepreneurs: what they have in common is that they became role models, morale builders, talent spotters, and inspirations. By highlighting the contributions of some of these leaders, we learn much more about the artistic history of Ottawa, its strengths and weaknesses, its lost possibilities, and its surprising successes. There remain many more stories to discover.

Leaders Remembered and Forgotten

The Ottawa Art Gallery’s chief curator, Catherine Sinclair, has written that trying to craft the story of the region through the lens of artistic practice is a complex effort, as the area has a variety of boundaries and includes several themes, events, and people. Many foundational stories about how the city came to be deserve to be told, featuring individuals from very different backgrounds. American-born settler Philemon Wright, who arrived on the site of the Chaudière Falls in 1806 and started the community, and British military engineer and Rideau Canal builder Colonel John By, whose decisions transformed the future city’s landscape, are well known. Many others, regrettably, are almost forgotten.

Who has heard of Amable Chevalier, Algonquin chief and War of 1812 veteran, who tried to defend Anishinābe territorial rights in the Ottawa River Valley from settler incursions? He unsuccessfully petitioned the colonial government on his people’s behalf, meeting and corresponding with Lord Dalhousie several times in the 1820s, and later with Dalhousie’s successor, Sir James Kempt. His pleas were ignored, and Chevalier died in 1833, leaving Indigenous peoples to continue their struggle against encroachments on their land and rights.

Or consider Joseph-Balsora Turgeon, who became the first francophone mayor of Bytown in 1853. Turgeon suggested the name “Ottawa” as a more historically appropriate name for the town. Dissatisfied with anglophone prejudice in the local Mechanics’ Institute, he helped found what would become the Institut canadien-français d’Ottawa in 1852. This organization promoted arts and letters and the sciences, such as a performance of a two-act play in 1853, which led to an ongoing commitment to francophone theatre. The institute also helped pay the tuition for francophone students of the College of Bytown (now the University of Ottawa) and launched the town’s first French newspaper, Le Progrès.

The predominance of the patriarchy in storytelling has until recently effaced the memory of many women who played vital roles in Ottawa. Furthermore, many communities have been overlooked. There is more to learn about Herbert and Estelle Brown, founders of one of the city’s first businesses owned by Black people (a dry cleaning and tailoring shop), recounted in the documentary Black in Ottawa, 2009, by Black filmmaker Patrice James. The same is true of William Poy, a refugee from Hong Kong who arrived in 1942 and became a successful civil servant and businessman—his daughter Adrienne Clarkson became Canada’s Governor General.

In the visual arts, many people contributed to Ottawa’s development and are worthy of attention. The following individuals have been highlighted, reflecting some of the city’s diverse communities as well as their individual contributions over the past two centuries.

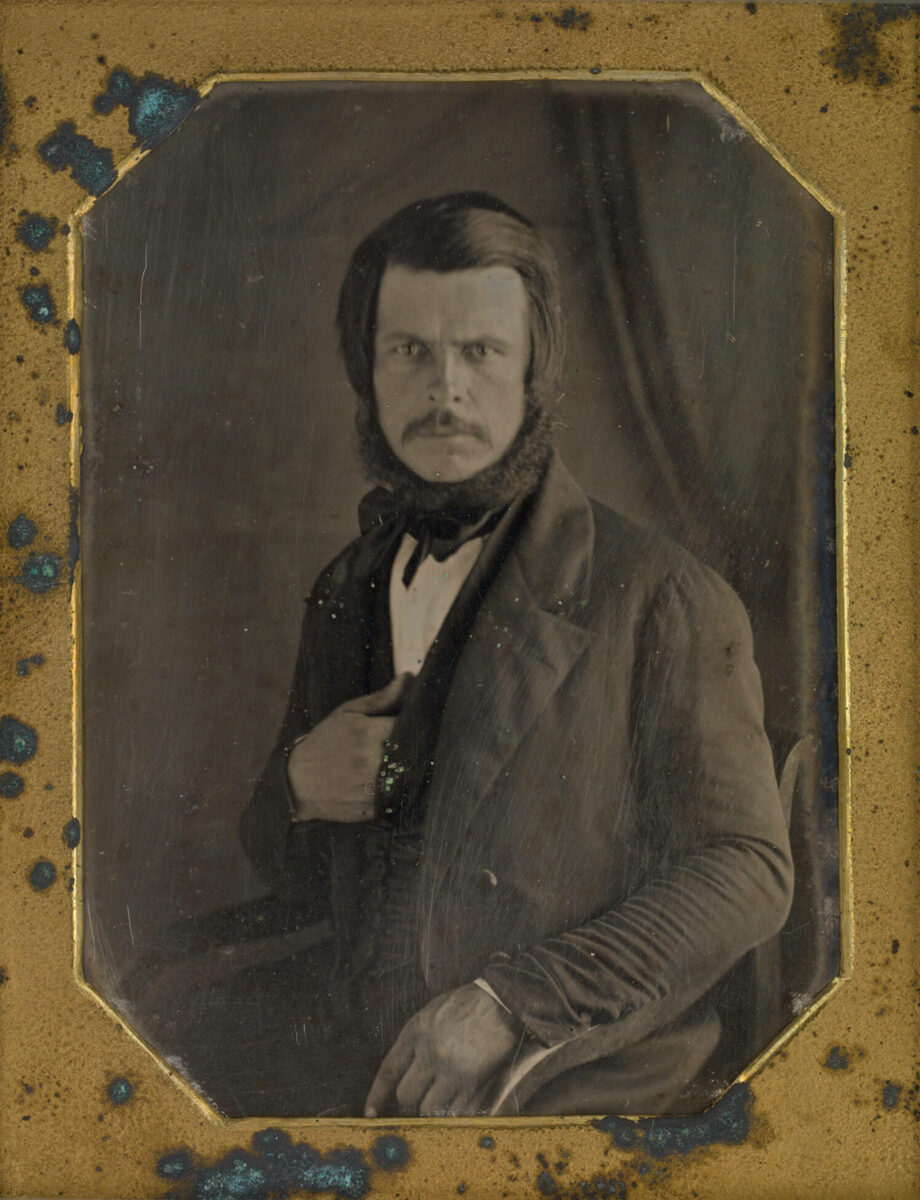

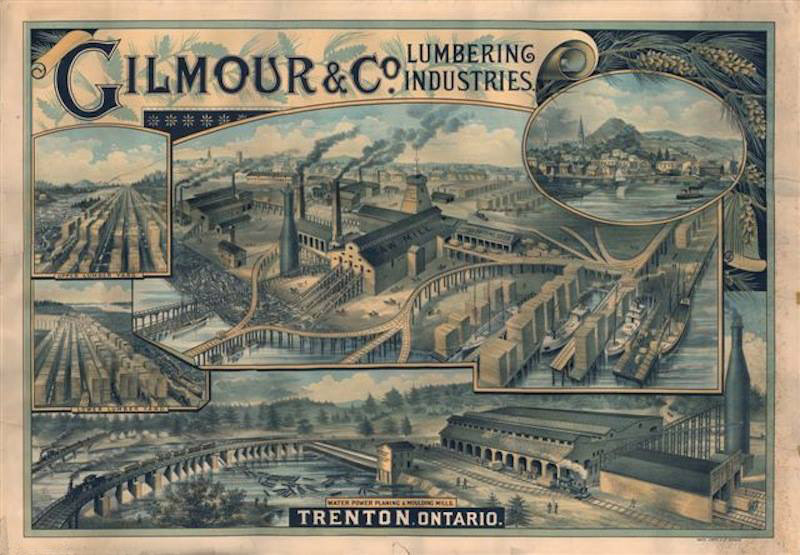

Allan Gilmour

Allan Gilmour was a timber merchant, lumber manufacturer, militia officer, art connoisseur, and collector. He played a prominent role in the group who met to discuss the formation of an art association in late May 1879, which included architects John William Hurrell Watts (1850–1917) and Frank S. Checkley, photographer William J. Topley (1845–1930), and engineer Sandford Fleming. The result was the Art Association of Canada, which proposed establishing a national gallery and an art school.

After the foundation of the Canadian Academy of Arts and the National Gallery in 1880, Gilmour remained active in artistic affairs as an honorary member of both the academy and the Ontario Society of Artists. He became one of the wealthiest men in Ottawa; when he died in 1895, his estate was valued at $1.45 million (almost $44 million in today’s dollars). His mansion on Vittoria Street was filled with an extraordinary collection numbering 146 artworks.

Born in Scotland in 1816, Gilmour was educated there before immigrating to Canada in 1832 with his cousin. They worked for a mercantile firm in Montreal, taking it over in 1840 and renaming it Gilmour and Company. In 1853, Gilmour moved himself and the company to Bytown to facilitate a shift into the sawn lumber market, and he eventually developed one of the largest timber operations in the country. When Gilmour retired from business in 1873, he travelled widely overseas before returning to Ottawa.

Gilmour became a major art patron, loaning works from his collection to the first Royal Canadian Academy of Arts exhibition in 1880. He was the best known of a group of Ottawa art collectors that included Fleming, James W. Woods, H.A. Bate, Edith Wilson, and members of the Edwards, Southam, and Powell families. He commissioned what might be Canada’s first horse portrait, Corbeau, a Trotting Horse, 1845, by Robert C. Todd (1809–1866), as well as two other paintings by this artist: The Timber and Shipbuilding Yards of Allan Gilmour and Company at Wolfe’s Cove, Quebec, Viewed from the South and The Timber and Shipbuilding Yards of Allan Gilmour and Company at Wolfe’s Cove, Quebec, Viewed from the West, both 1840. He also owned works by Cornelius Krieghoff (1815–1872) and Franklin Brownell (1857–1946). His remarkable collection seems to have been dispersed at his death.

Jennie (Jeanette) Russell Simpson

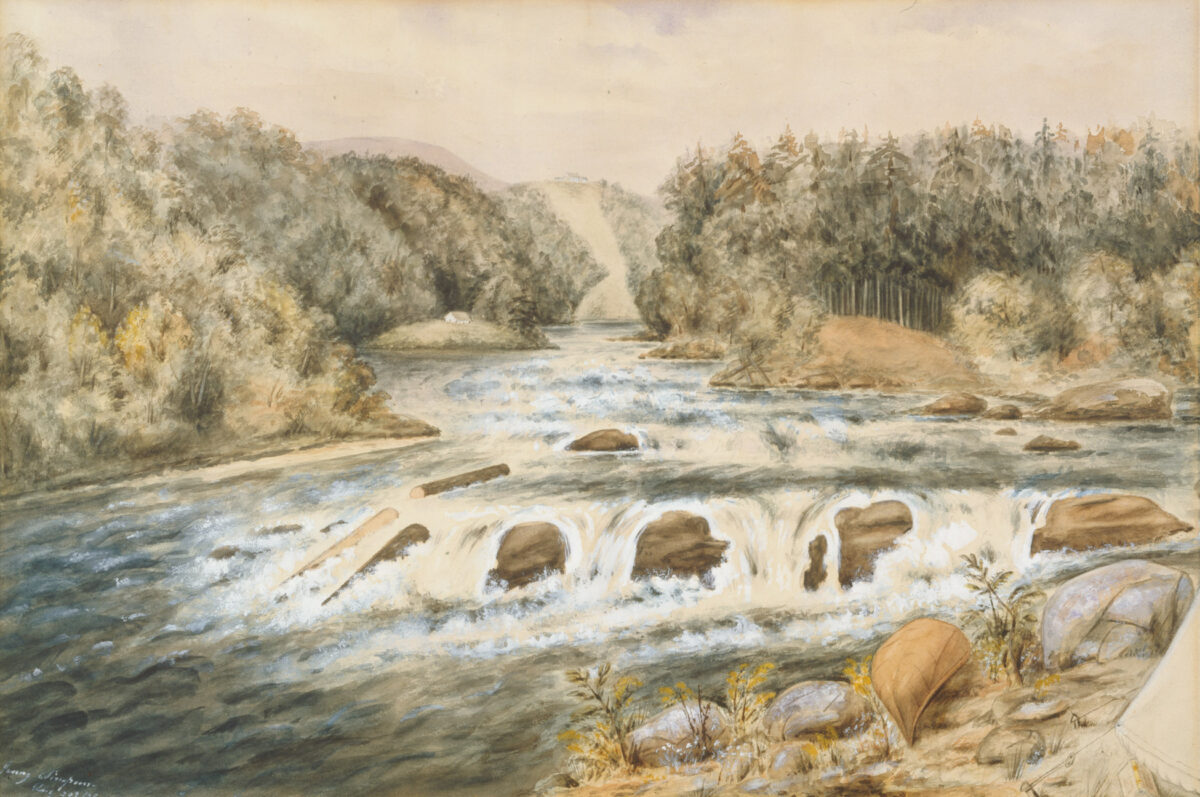

Jennie Russell Simpson was an artist and active member of several important organizations, including the Women’s Art Association of Ottawa, the Ottawa Women’s Canadian Club, the National Council of Women, the League of Nations, and the Historic Landmarks Association. Most of all, she is associated with the Women’s Canadian Historical Society of Ottawa and with the Bytown Museum, for which she was the first curator, yet her name is almost invariably omitted from the historical narrative.

Jeanette Russell was born in 1847 in Montreal, the daughter of Andrew Russell, a surveyor who eventually assumed a senior position in the Department of the Interior after Confederation. Her uncle Alexander Jamieson Russell was also a surveyor, public servant, author, and artist, whose creative talent seems to have been passed on to his niece. Little is known of Russell’s early life, although she may have taken art lessons while in Montreal. She moved with her family to Ottawa in 1866, marrying civil servant John Barker Simpson in 1869. She demonstrated her artistic abilities in her portraits of her father-in-law in 1879 and her father in 1880, and in View Taken from Wright’s Island on the Gatineau River at Farmer’s Rapids, 1879.

Simpson had a daughter, Amy, and seems to have moved within upper-class Ottawa social circles. In the 1890s she joined a number of women’s organizations, including the Women’s Art Association of Ottawa, founded in 1898. In the middle of the next decade, she was involved with the Women’s Canadian Historical Society, assisting with the preparation of its 1906 exhibition catalogue, as well as lending artifacts. She became the society’s recording secretary, was on the executive committee, designed their logo, and published in their journal Transactions.

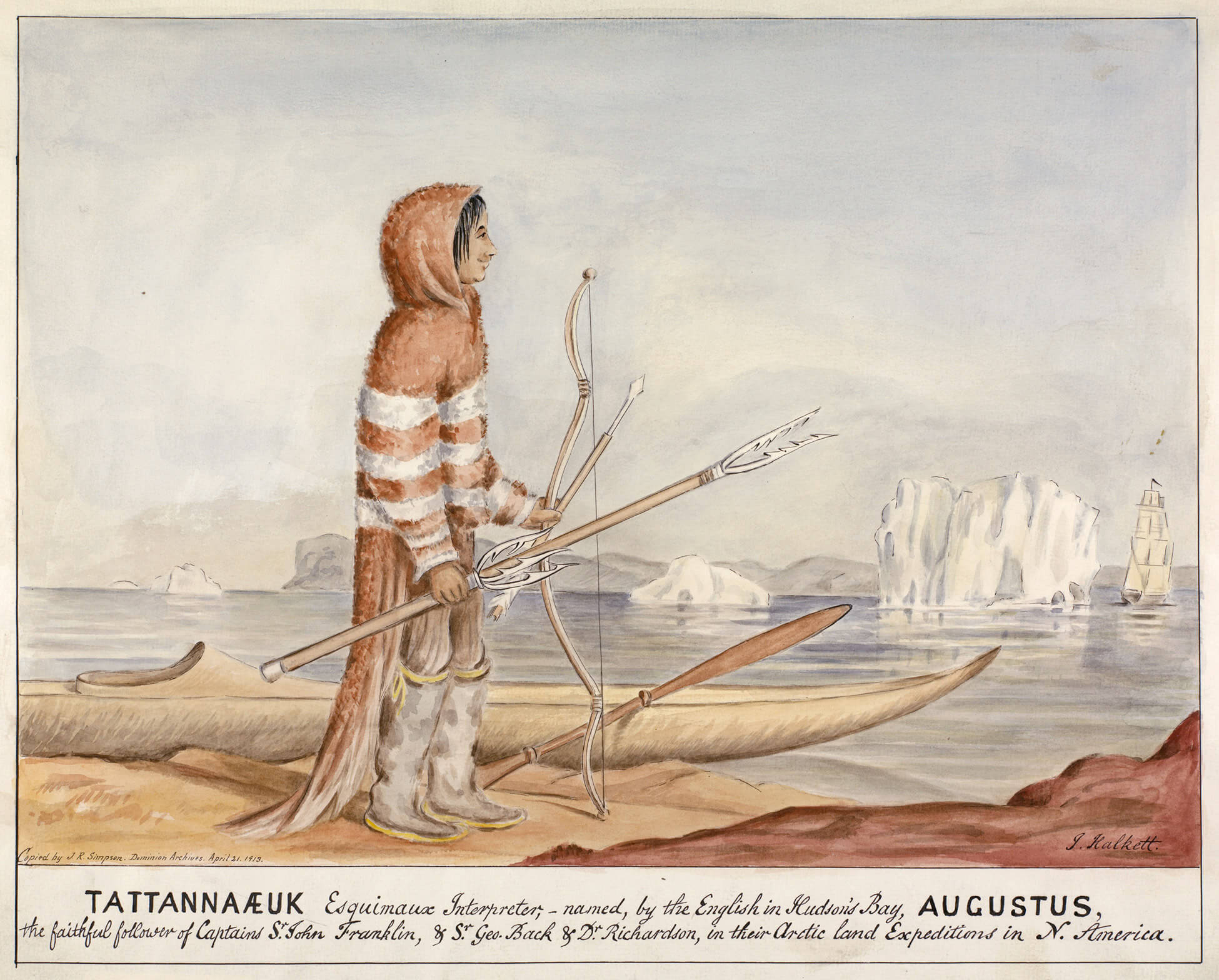

Simpson also began working as a copyist for the Dominion Archives, commissioned to provide watercolours based on printed sources. One of these, Tattannaaeuk, Esquimaux [Inuit] Interpreter—Named, by the English…Augustus, 1913, demonstrates remarkable skill and virtuosity. Her artistic career is otherwise difficult to trace, as no exhibit or sales records have been located.

Her lasting contributions to the arts were administrative. The male-dominated Royal Society of Canada, founded in 1882, created an initiative called the Historic Landmarks Association of Canada (HLA) in 1907 to prepare for the Quebec Tercentenary the following year. The organization then languished until Simpson was hired in 1914 as its only paid employee (at an annual salary of $50) to revive its fortunes. She initiated annual reports in 1915 and increased the membership almost fourfold in just four years. Upon her retirement in 1921, the HLA president acknowledged the association’s debt to her.

Simpson remained an active member of the Women’s Canadian Historical Society, and at the age of seventy-six she became the first curator of the Bytown Historical Museum, which the society had opened in 1917. She was responsible for major acquisitions and published the first collection catalogue in 1926. She died in April 1936. Her legacy, and that of many women like her, who kept the memory of the early history of Ottawa alive through their pioneering efforts, merits far more recognition.

Madge Macbeth

Madge Macbeth bridged several eras in Ottawa life, and she should be remembered for her long career as a writer, reporter, playwright, arts critic, and photographer—all accomplished as a single mother—in an age when women were negotiating their roles in society with great difficulty. She helped found the Ottawa Little Theatre in 1913, encouraged Yousuf Karsh (1908–2002) early in his career, and was the first woman president of the Canadian Authors Association.

Born Madge Hamilton Lyons in Philadelphia in 1878, she showed literary talent early on, attempting to revise the Bible at age three, and soon writing and producing neighbourhood plays. After her father died in 1888, her mother moved the family from place to place, eventually ending up in London, Ontario. Macbeth attended Hellmuth College there, where she ran the school paper. She then toured as a vaudeville musician and actress before marrying civil engineer Charles William Macbeth in 1901. They moved to Ottawa in 1904, but four years later Madge was left a widow with two sons to support after her husband died of tuberculosis.

She turned to writing and journalism, publishing her first two stories in Canada West and the Canadian Magazine. She became known for her interviews with Members of Parliament and released her first novel, The Winning Game, in 1910, followed by several more over the next five decades (two using the pseudonym Gilbert Knox). These included thinly veiled satires of Ottawa social life, such as Shackles (1923), in which her feminist beliefs are clearly expressed. She also wrote travelogues and local histories, as well as publicity brochures for the Canadian Pacific Railway. Her Ottawa Citizen column, “Over My Shoulder,” highlighted her presence as a personality in the city. Her work appeared in Saturday Night, Maclean’s, the Winnipeg Free Press, and the Toronto Star Weekly.

Perhaps as early as 1905, Macbeth also learned photography, eventually taking hundreds of shots. She took pictures of Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier and his wife and the interior of Laurier House, Governor General Earl Grey, and other prominent individuals, including Sir Robert Borden; Charlotte Hanington, chief superintendent of the Victorian Order of Nurses; and painter Mary Riter Hamilton (1873–1954). Her images appeared in the Canadian Courier, and they accompanied her articles.

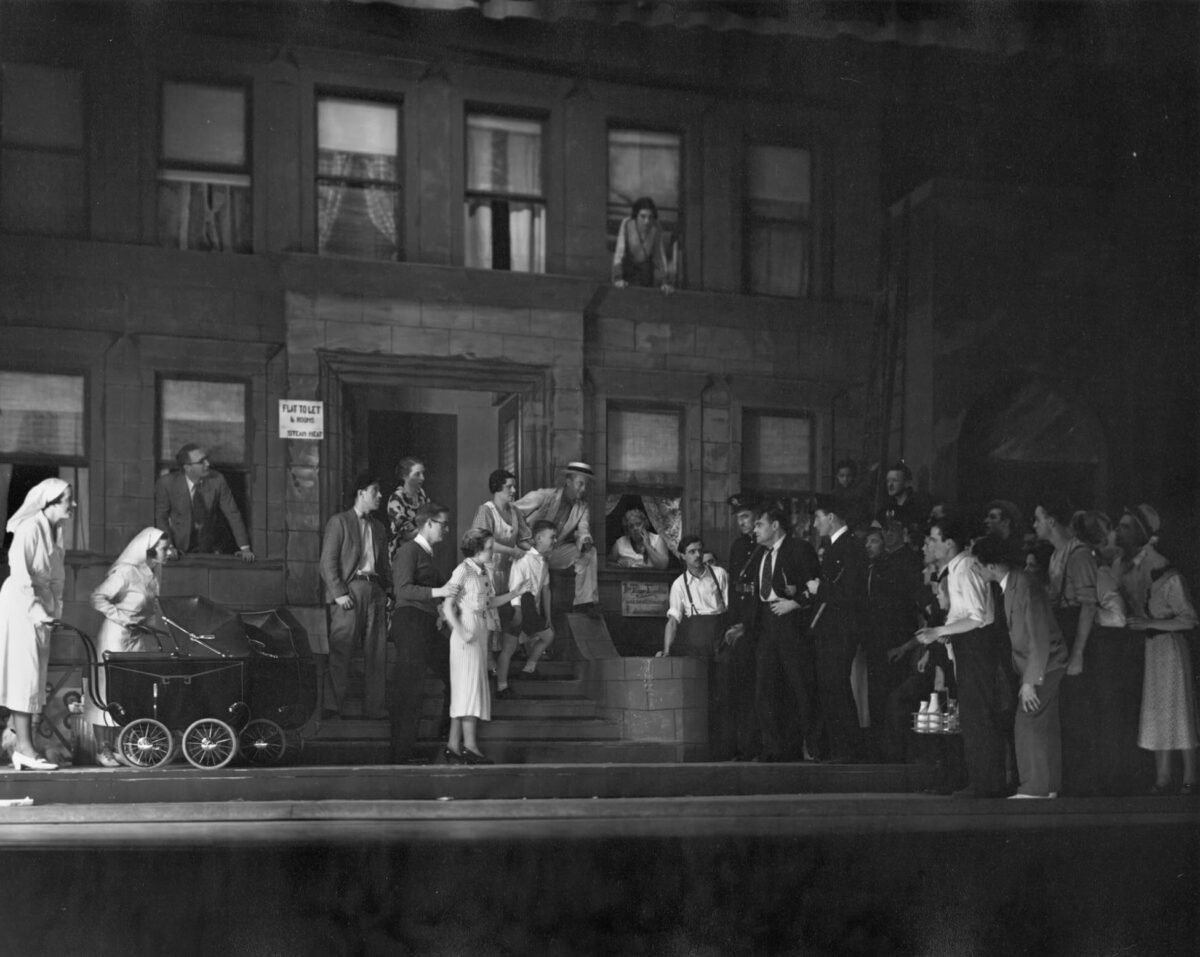

Macbeth was also an art critic, reviewing many exhibitions during her career. Karsh cited her as an early friend and supporter, and he photographed her multiple times in the 1930s. Her portrait was drawn by Goodridge Roberts (1904–1974), probably around 1931–32. Her interest in theatre led her to become a founding member of the Ottawa Drama League in 1913 (later the Ottawa Little Theatre), one of the oldest community companies in Canada.

At various times, Macbeth was president of the Ottawa Drama League, the Ottawa Women’s Press Club, and the Canadian Authors Association. When she died in 1965, she was remembered as an Ottawa literary personality.

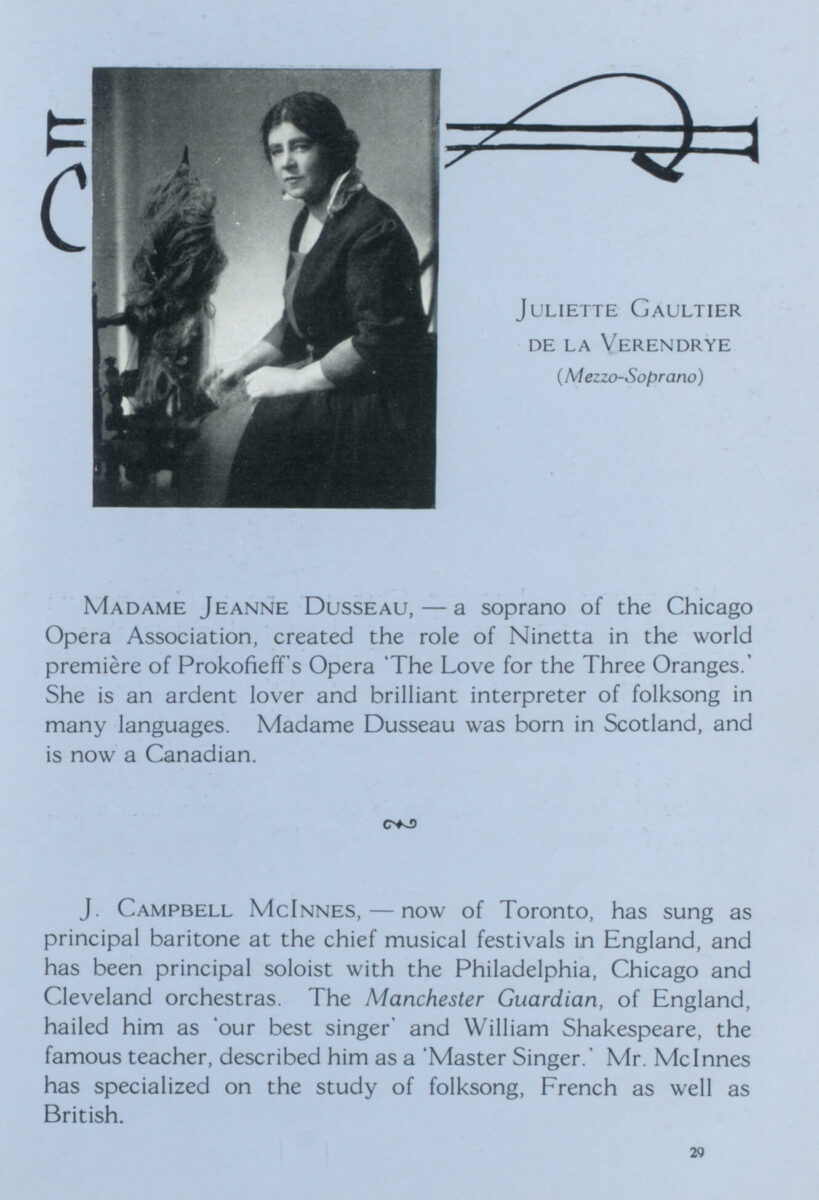

Juliette Gaultier de la Vérendrye

Juliette Gaultier de la Vérendrye (née Gauthier) is significant as an ethnological musician and because of her efforts to collect the material culture of the Algonquins of Kitigan Zibi and Pikwàkanagàn. She spent the 1930s and 1940s learning about the Algonquins of the Gatineau Valley. She eventually bought or received 475 artifacts, including birchbark containers, bitten bark artworks, and other objects, such as a birchbark suitcase created by Madeleine Clément (1887–1975) that is decorated with geometric and vegetal designs. It was one of the largest such collections in existence, and many of the pieces Gaultier acquired are now in the Canadian Museum of History.

Born in Ottawa in 1888, she was the niece of Sir Wilfrid Laurier. Her older and more famous sister was Eva Gauthier, a mezzo-soprano who was a friend of Maurice Ravel and Erik Satie and premiered their music in North America. Juliette took music lessons as a child and attended McGill University in Montreal, where she won a four-year scholarship to Europe to study violin and voice. She made her professional debut around 1910 and followed Eva to New York, where she taught singing from 1922 to 1925. In 1927 she spent four months performing avant-garde and experimental music at a New York playhouse.

Gaultier befriended a wide variety of individuals, including American artist W. Langdon Kihn (1898–1957), Group of Seven painter Arthur Lismer (1885–1969), composer Marion Bauer, and Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King. She also knew National Museum anthropologists Marius Barbeau and Diamond Jenness, who guided her as she took up ethnomusicology. Her new pursuit led her to perform recitals of Acadian, Inuit, and Indigenous folk music, much of which she had collected and then arranged. She learned Inuktitut and the languages of several Pacific Coast First Nations in order to do so.

At the 1927 Canadian Folk Song and Handicraft Festival in Quebec City, she sang songs that had already been gathered by anthropologists Ernest Gagnon and Barbeau, drawing her First Nations, Inuit, French Canadian, and Acadian repertoires from the archives of the National Museum and the American Museum of Natural History, New York City. She also borrowed Indigenous clothing (she wears the Anticock coat, date unknown, in a portrait by Kihn), intending to create an aura of authenticity (at a time when the term “cultural appropriation” had not yet been heard). Her musical interpretations were praised by many, including Arctic explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson, who wrote to Jenness, “So far as I know this is the first time that Eskimo Bay [Inuit] songs have been sung just as they are instead of being merely used as the basis or ‘inspiration’ for some sort of elaboration.”

Gaultier’s interest in Algonquin material culture was inspired by the research of Edward Sapir of the Geological Survey of Canada and American anthropologists Frank Speck and Frederick Johnson. She was also drawn to French Canadian folk culture. Many of her collections were put on display at the Gatineau Park Museum in Kingsmere, Quebec, which she directed from 1949 to 1953. After the museum closed in the 1950s, she donated them to the National Museum (now the Canadian Museum of History). Gaultier died in Ottawa in 1972, a nearly forgotten figure in the region’s history.

Eric Brown

In 1910, Eric Brown was named the first director of the National Gallery of Canada. Well known for building its collections and for championing the work of Tom Thomson (1877–1917), the Group of Seven, and Emily Carr (1871–1945), Brown played an enormous role on the national stage. At the same time, he and his wife, Maud, were active in the local Ottawa art scene.

Brown was born in Nottingham, England, in 1877, the younger brother of British landscape painter Sir Arnesby Brown (1866–1955). He did not attend university, and at the age of thirty-two was a failed farmer. But while visiting his brother in 1909, he met F.R. Heaton, head of Montreal art dealer W. Scott and Sons. Heaton encouraged Brown to immigrate to Canada, and he was soon hired to superintend a loan exhibition of British paintings in Montreal, and then to work for the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario). Brown quickly became the secretary for the federal government’s Advisory Arts Council, chaired by Byron Edmund Walker, as well as the curator of the National Gallery. The job enabled Brown to marry Florence Maud Sturton, a teacher and graduate of Cambridge University.

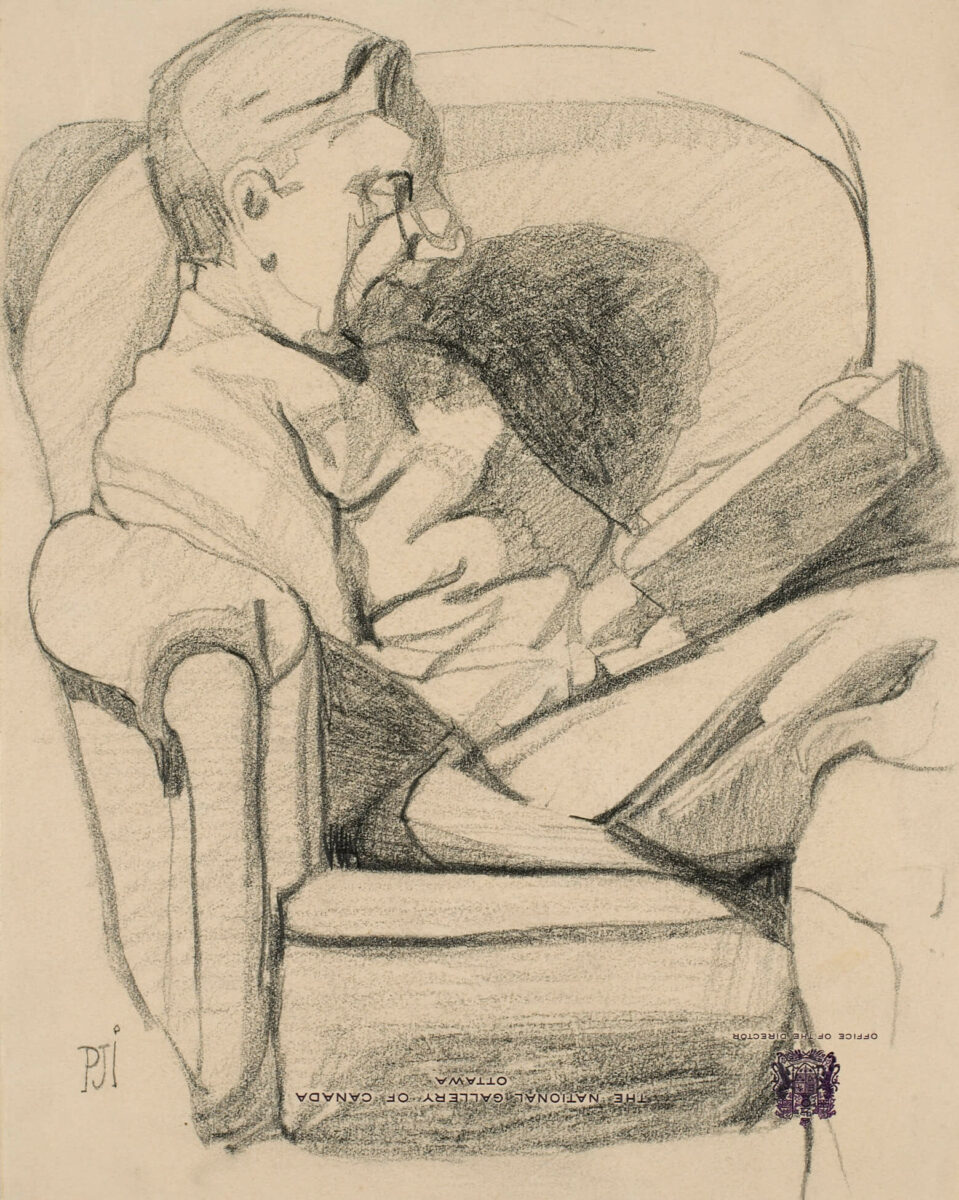

In Ottawa, the Browns, who had a strong partnership, developed deep ties within the arts community. Their social circle included the National Gallery’s assistant director H.O. McCurry and his wife, Dorothy; art critic and gallery trustee Newton MacTavish; Marius Barbeau, the National Museum’s curator of ethnology; Kathleen Fenwick (later to become the gallery’s curator of prints and drawings); writer Madge Macbeth; and artist Pegi Nicol MacLeod (1904–1949). Maud described the latter, and the Browns’ home life, in her memoir Breaking Barriers (1964): “It was a happy day when we met Pegi Nicol… an astonishing person… like a very much younger sister, and our house was her second home. We had special fun when Arthur Lismer was in Ottawa. Usually Harry and Dorothy McCurry, Kathleen Fenwick, Peggy, and often one or two others, would come in the evening…. we would all sit round sketching each other while Eric read from 1066 and All That or The Young Visitors. We laughed and chatted all evening.” Brown was also a friend and admirer of Franklin Brownell. He not only arranged for a full-scale retrospective of his work at the National Gallery in 1922, but he acquired several of his pieces for the institution. He also purchased art from Ernest Fosbery (1874–1960), whose prints he admired, and from Florence McGillivray (1864–1938)—Midwinter, Dunbarton, Ontario, 1918, was one of his choices.

Interested in photography as well as painting, printmaking, and sculpture, Brown supported Ottawa practitioners, including Harold F. Kells (1904–1986) and Clifford M. Johnston (1896–1951), in their efforts to establish the Canadian International Salon of Photographic Art, which was first held at the National Gallery in 1934. In the catalogue, Brown expressed the hope that it would become an annual event. It did, and exhibitions were held until 1939—but the declaration of war, combined with his death that same year, would lead to the salon’s cancellation. Brown had a major influence on the arts in Ottawa. While his close associations with the community encouraged some local artists and inhibited others, his positive impact was immeasurable.

Vincent Massey

Vincent Massey, a leading figure in the national arts scene over several decades, was also the first Canadian-born Governor General, serving from 1952 to 1959. He ushered in an era of growing government commitments to the arts, and after his years in office he set an unmatched philanthropic example to other Canadians with his contributions in art, education, and culture.

Born in 1887 to the Massey-Harris family of manufacturing fame, Massey was educated at the University of Toronto and Oxford University. He served in the Canadian army in the First World War, was briefly the president of the family company, and for five weeks in fall 1925 was a member of Prime Minister Mackenzie King’s Cabinet. He was appointed Canada’s first official envoy abroad, serving as high commissioner to the United States from 1926 to 1930. In 1935 he became high commissioner to the United Kingdom, a post he held throughout the Second World War.

Massey had a lifelong interest in cultural affairs and artistic developments. While living in Britain he served as a trustee of the National and Tate Galleries, and from 1943 to 1945 he chaired the Tate’s board of governors. Upon his return to Canada, Massey became chair of the National Gallery of Canada (1948 to 1952) and chancellor of the University of Toronto (1948 to 1953). Between 1946 and 1950 the Massey foundation donated a large collection of early twentieth-century British art to the National Gallery, including works by Stanley Spencer (1891–1959), Vanessa Bell (1879–1961), Duncan Grant (1885–1978), Gwen John (1876–1939), Derwent Lees (1884–1931), Paul Nash (1889–1946), and others—The Blue Gloves, c.1923, by William Nicholson (1872–1949) and Spring in the Ravine, c.1933, by Frances Hodgkins (1869–1947) were among the highlights of the gift.

His most important legacy was the Massey-Lévesque Report, which appeared in June 1951 and summarized the findings of the two-year-long Royal Commission on National Development in the Arts, Letters and Sciences that he had co-chaired. As early as 1944, sixteen Canadian arts groups had joined to coordinate efforts to have the arts included in the federal government’s postwar reconstruction efforts. The Commission, created in 1949 in response to their demands, conducted a serious examination of the country’s cultural life, holding 114 public meetings throughout Canada at which more than 1,200 witnesses appeared.

The report argued that the arts could be a means to build up Canada’s identity. It advocated for the establishment of a national board to administer public funds for the encouragement of the arts, humanities, and social sciences, and it also called for strengthening Canadian universities and the public broadcasting system—two recommendations the federal government quickly accepted. The conclusions led to the establishment of the National Library of Canada in 1953 and the Canada Council for the Encouragement of the Arts, Letters, Humanities and Social Sciences in 1957.

As Governor General, Massey promoted a national festival of the arts. Although he did not specifically advocate for a national arts centre, his belief in government support for theatre and performance resonated with both Ottawa arts advocate Hamilton Southam and Liberal cabinet minister Lester B. Pearson, who ensured that this concept became part of the planning for Canada’s centennial.

He was a generous and long-time supporter of the National Gallery. His donation of British art—which included his own portrait, painted by Augustus John (1878–1961)—was highly significant for the institution. He was equally generous with Canadian works. Following his death in 1967, one hundred pieces, by David Milne (1882–1953), Sarah Robertson (1891–1948), Will Ogilvie (1901–1989), Charles Comfort (1900–1994), A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974), F.H. Varley (1881–1969), Lawren S. Harris (1885–1970), and others, were donated to the gallery. This gift included the magnificent small oil by Tom Thomson Petawawa Gorges, Night, 1916, and Robertson’s iconic Joseph and Marie-Louise, c.1930.

John Robertson

One of the most important figures in the Ottawa arts scene in the period after the Second World War was John Robertson, a gallery owner, dealer, and promoter of contemporary and Inuit art. In founding his business, Robertson stated his desire “to encourage younger Canadian painters, and concentrate on the work of outstanding younger sculptors. Variety will be the key note so long as the highest standard is maintained.” For artists to find success and acceptance in Ottawa in the 1950s and 1960s, his community leadership was critical.

Born in Toronto in 1915, Robertson served in the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), during which time he met his future wife, Mary Gordon, also a serving RCAF member. After the war, he joined the National Gallery of Canada as an accountant, but, taking a leap of faith in 1953, he left to open a commercial art gallery in downtown Ottawa. His initial shows were attended by senior bureaucrats, as well as Governor General Vincent Massey, and featured contemporary Canadian art by Eva Landori (1912–1987), Takao Tanabe (b.1926), Victor Tolgesy (1928–1980), and Gerald Trottier (1925–2004), among others.

In cooperation with city officials and local artists, Robertson provided advice for and eventually became director of the Municipal Art Centre, a small brick building in Ottawa South, which opened in October 1953. Classes for all ages were initially taught by such artists as Trottier, Tolgesy, and Theo Lubbers (1921–2013). Robertson continued as the director until 1960 but would remain involved for almost two decades.

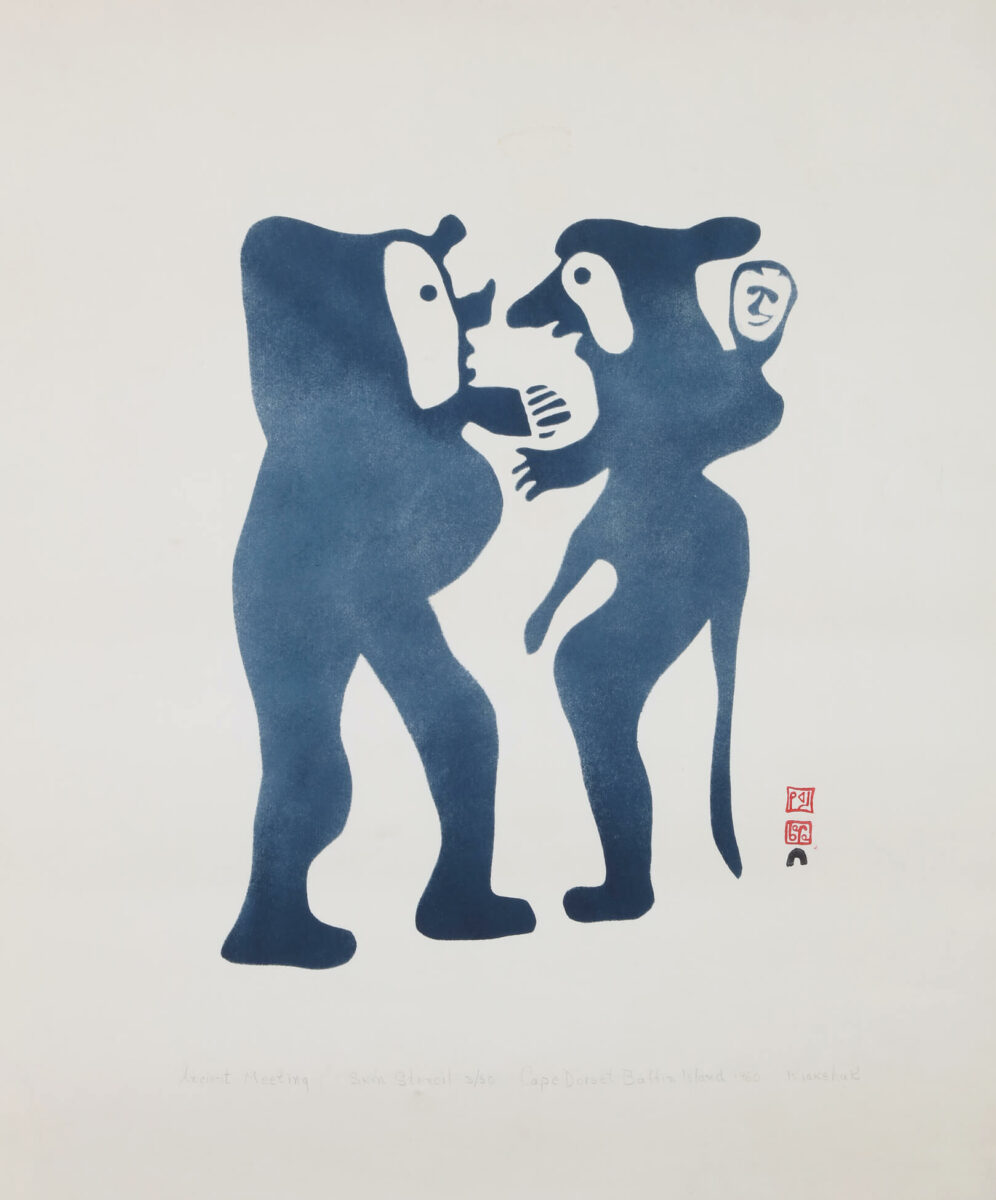

Robertson’s deep interest in Inuit art began in part because of his friendship with government agent James Houston, whose initiatives had revealed tremendous talent across the Arctic. The Robertsons travelled extensively in the Canadian North in the 1950s and 1960s in search of acquisitions for their business and personal collection, seeking out both sculptures and graphic works, such as Ancient Meeting, 1960, by Kiakshuk (1886–1966). Houston later noted that “Robertson Galleries was the second gallery in the world… to promote Inuit art.” It held major exhibitions of Inuit prints in 1967 and 1971, of sculpture in 1969, and of work by Kananginak Pootoogook (1935–2010) in 1975. It regularly displayed pieces by Pitseolak Ashoona (c.1904–1983), Kenojuak Ashevak (1927–2013), and other Inuit artists. From 1968 to 1974, Robertson served on the Canadian Eskimo Arts Council, an organization created by the Canadian government to promote the work of Inuit artists.

One of the founders of the Professional Art Dealers Association of Canada in 1966, Robertson served as its president for several terms. He was also one of the first members of the Canadian Cultural Property Export Review Board in 1977, the federal agency established to ensure that Canada’s cultural property was protected, preserved, and made accessible to the public. He remained associated with it for more than twenty years. Throughout his professional career and beyond, he was friends with surviving members of the Group of Seven, many Ottawa artists, and Inuit artists from across the North.

The Robertsons sold their gallery in 1976 but continued acquiring Inuit art. Between 1985 and 1996 they donated more than 240 Inuit prints, drawings, sculptures, and artifacts to the Agnes Etherington Arts Centre at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, as well as a substantial collection to the Carleton University Art Gallery. Remembered for his gallery expertise and good humour, Robertson died on February 23, 2001.

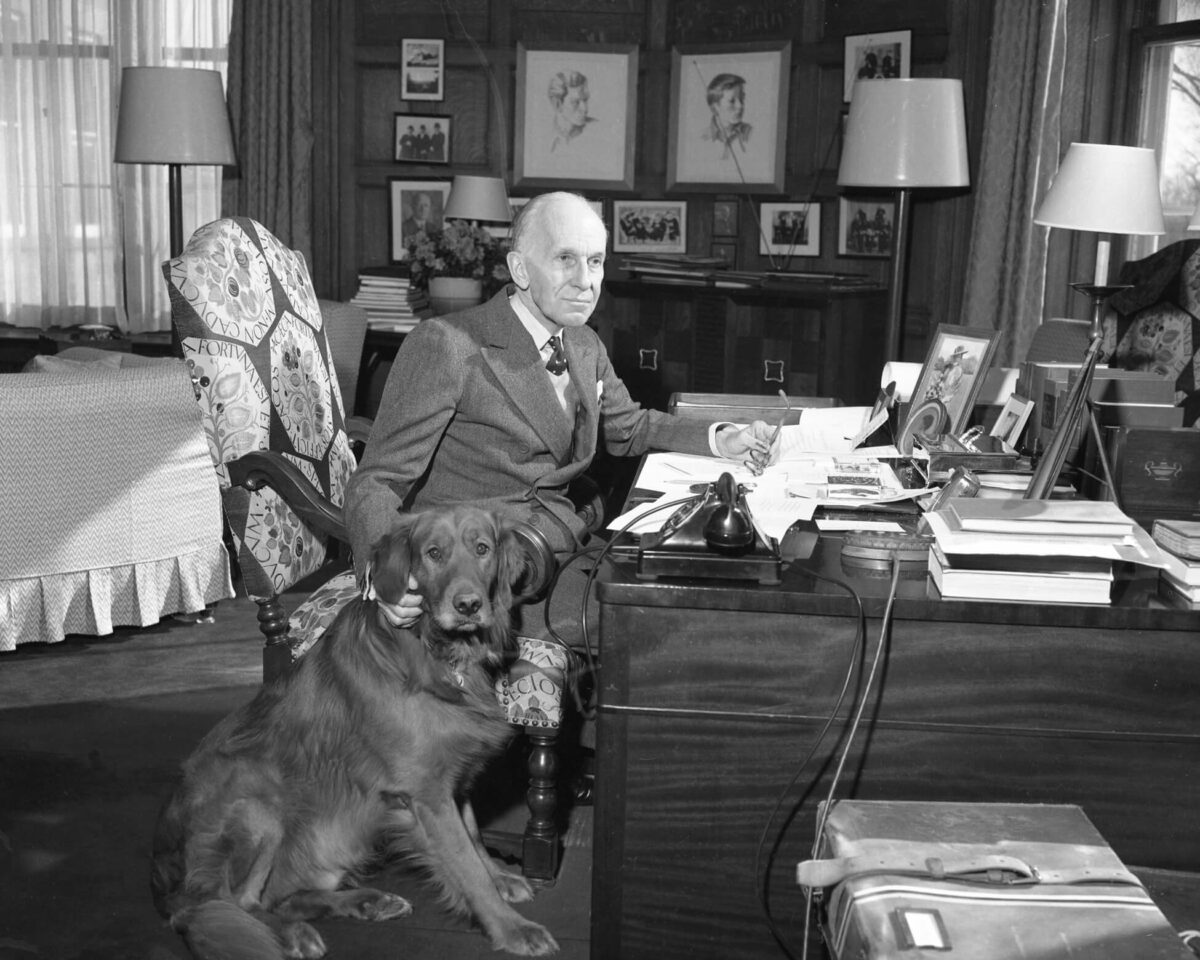

Otto “Jack” Firestone

Beginning in the 1950s, Otto “Jack” Firestone and his wife, Isobel, amassed a collection of Canadian art, which by 1972 had grown to over 1,600 works. They built Belmanor, a spectacular home in Rockcliffe Park, to house it. While a small coterie of friends and colleagues knew of the extent of the couple’s holdings, they were not publicly accessible. In 1991, however, the Firestone Collection of Canadian Art was transferred to the Ottawa Art Gallery (OAG), which has catalogued, conserved, and exhibited it. Firestone would remark at a 1992 opening, “The collection is now standing on its own… here it has room to breathe.” It is the cornerstone of the gallery’s holdings.

Firestone was born in Austria in 1913, but like many others, he and his family fled fascism for England in the 1930s. In 1938 he came to Canada to study, graduating from McGill University in 1942 before moving to Ottawa to work for the federal government. In 1947 he married concert pianist Isobel Torontow. To learn more about his adopted country, Firestone made repeated visits to the National Gallery of Canada in the 1940s and 1950s, and he and his wife began to build their own collection. They visited the studios of artists such as Lawren S. Harris (1885–1970), Jack Shadbolt (1909–1998), and A.J. Casson (1898–1992) to buy works, often becoming good friends in the process. They became particularly close to A.Y. Jackson, then living in Manotick, Ontario.

The Firestones are the most notable of several Ottawa collectors who emerged in the postwar period. As they built their collection, they contemplated what to do with it. Eventually, they decided to donate the house and its contents, together with an endowment fund, to the Ontario Heritage Foundation (OHF) in 1972, since there was no municipal organization in existence to receive it. The couple continued to live in the house, while the OHF became responsible for the conservation of the art and maintained the property. Firestone became the de facto curator, and it was open by appointment to teachers and art classes, researchers, and the general public.

By 1990, Firestone and his family had moved to a new home, and the OHF was faced with decisions regarding the future of both Belmanor and the art collection. The possibility that the latter might be transferred to a public museum in Toronto was met with fierce resistance from the community. The City of Ottawa and the Gallery at Arts Court (as the Ottawa Art Gallery was then known) proposed instead that the “Collection be exhibited, managed and conserved in environmentally controlled new spaces in Ottawa’s municipal art gallery.” In September 1991, the OHF accepted this bid. The Firestone Collection is pan-Canadian, but it includes many works by such Ottawa artists as Henri Masson (1907–1996), Bruce Garner (b.1934), Joyce Devlin (b.1932), Art Price (1918–2008), Ralph Burton (1905–1983), and Jackson. It enabled the OAG to explore the city’s artistic past and gave the new gallery a legitimate place among Canadian art institutions.

While Firestone will always be remembered as one of the greatest art patrons in the region, he also ran real estate and broadcasting businesses, and he played a key role in the adoption of universal healthcare in Canada. The quintessential immigrant, he became a true Canadian. He passed away in 1993.

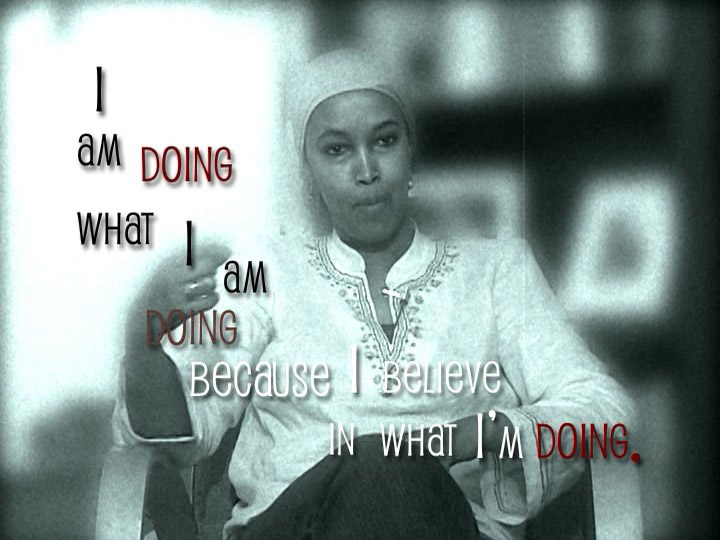

Mela Constantinidi

Mela Constantinidi was the director of the Ottawa Art Gallery (OAG) for seventeen years, until June 2010, taking over from the founding director, Mayo Graham. During her tenure, she grew the museum’s collections and reputation through an acquisition program that would map and record contemporary Ottawa-Gatineau art. With the curatorial team, she sought out artists working in photography, film, sculpture, crafts, performance, and Conceptual art, brought the work of many Indigenous artists to public attention, and worked with francophone artists from the Gatineau region, LGBTQ artists, and artists from minority communities, all of whom were given a voice and a venue.

Constantinidi earned an art history degree from the Institut d’art et d’archéologie at the Sorbonne, Paris, in the early 1970s. Her career trajectory included seven years working in the exhibitions program for the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, followed by thirteen years at the Canada Council for the Arts, where she was successively the manager of the International Exhibition Program and assistant head and arts officer of the Visual Arts Section.

Given this experience and her connections to the contemporary art world, Constantinidi was well suited to the task of managing the Ottawa Art Gallery. The works of such artists as Pat Durr (b.1939), Barry Ace (b.1958), Lynne Cohen (1944–2014), Evergon (b.1946), Annie Pootoogook (1969–2016), Juan Geuer (1917–2009), and Leslie Reid (b.1947) were acquired either through purchase, as with Reid’s Calumet: Five, 2003, and Geuer’s Al Asnaam: the People Participating Seismometer, 1980, or by donation, as with Heat Rise, 1962, by Kenneth Lochhead (1926–2006) or That’s All it Costs, 1991, by Ron Noganosh (1949–2017). In 2008, on the gallery’s twentieth anniversary, the exhibitions Contemporary Art Collection and Evidence: The Ottawa City Project featured a wide selection from the more than 1,000 pieces accessioned under Constantinidi’s direction.

The OAG regularly presented several exhibitions a year, creating an exciting atmosphere for artists in the community. Shows celebrating the creativity of Indigenous artists Noganosh, Ace, Pootoogook, Jeff Thomas (b.1956), Rosalie Favell (b.1958), Greg Hill (b.1967), and Barry Pottle (b.1961) were highly praised by such critics as Nancy Baele and Paul Gessell. The latter’s review of the 2008 exhibition Evidence enthused about Hill’s Cereal Box Canoe, 2000, calling it one of “many down-and-dirty portraits of Ottawa,” and praised the exhibition as “a selection of Ottawa’s greatest hits of the past decade.” The OAG also worked closely with artist-run spaces such as SAW, Gallery 101, Artengine, and Enriched Bread Artists; the University of Ottawa fine arts program; and the Carleton University Art Gallery and its art history department.

Constantinidi’s achievements were formally acknowledged in 2010 upon her retirement. She received the Ontario Association of Art Galleries Lifetime Achievement Award, and the City of Ottawa named her the winner of the Victor Tolgesy Arts Award, recognizing how much she had enriched cultural life in the city.

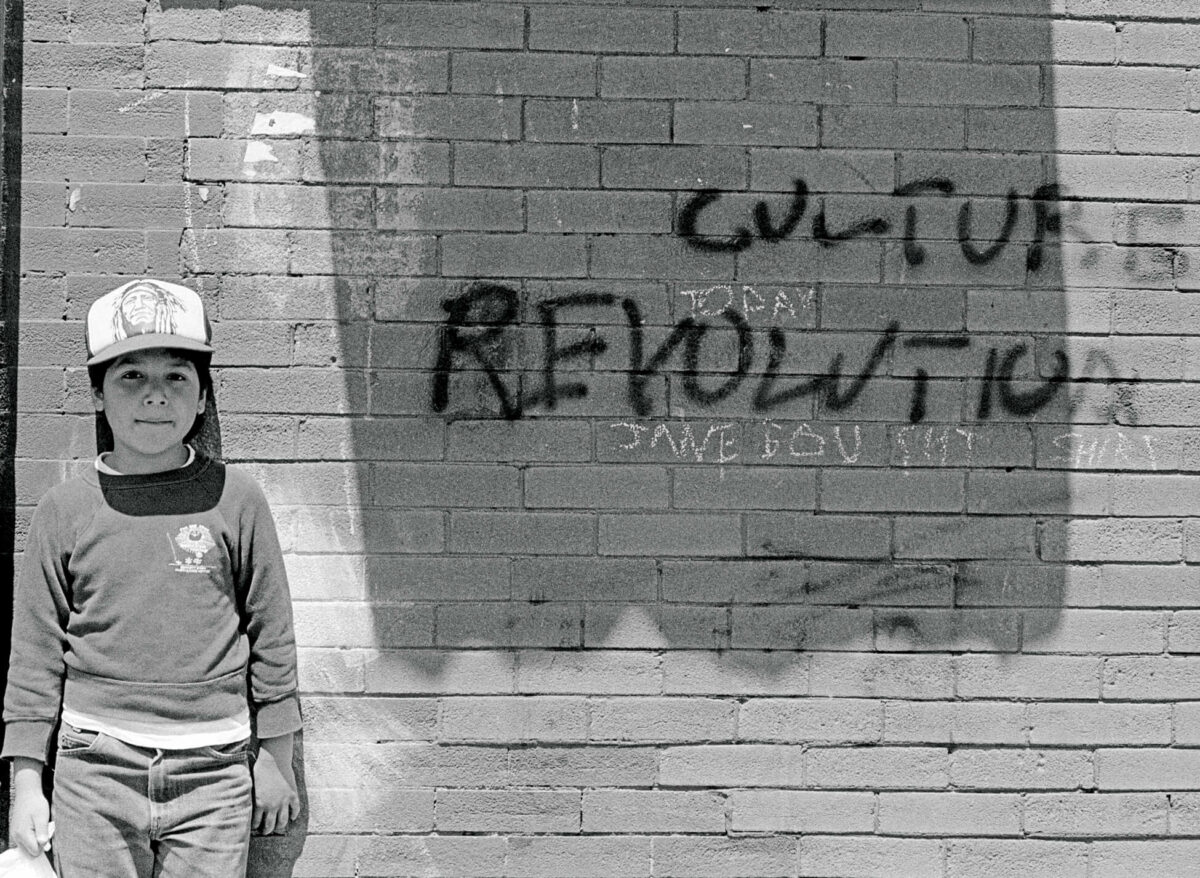

Jeff Thomas

Community leaders are not always in charge of organizations, nor do they necessarily head committees seeking changes in public policy or funding. Sometimes, they show the way. Jeff Thomas is an incredible example of how one person can affect the course of social development. He is a self-described “Urban Iroquois” whose life changed after a car accident left him seriously injured in 1979. He has described his subsequent career trajectory as follows: “I turned to my interest in photography to begin a new life and focus on confronting photo-based stereotypes of aboriginal people. My research of photographic history pointed out two significant absences that would become the point of departure: The first was photographs depicting aboriginal people living in cities and the absence of images produced by aboriginal people. I was frustrated by the silence and challenged to stimulate conversations that did not exist.”

Born in Buffalo to parents from the Six Nations Reserve in Brantford, Ontario, Thomas grew up in northern New York State and completed an American studies degree at the University of New York. During his convalescence after the accident, his early interest in photography evolved into a professional practice. After moving to Toronto in 1984, he discovered the Native Indian / Inuit Photographers’ Association, which he described as part of a “new movement in defining ourselves and talking and just realizing that we weren’t alone.” Thomas made Ottawa his permanent home in 1991.

Thomas’s Bear Portrait series in 1984 forced viewers to compare stereotypical depictions of Indigenous peoples with the current realities of late twentieth-century Indigenous existence. He has continued to create works that confront such representations in a number of series, including Powwow Images, 1985; Scouting for Indians, 2000; Who’s Your Daddy? Four Hundred Years Later, 2008; and Resistance Is (Not) Futile, 2011. His photographs of his son, Bear Witness (Ehren Thomas), Adrian Stimson, Greg Hill, and others in front of the Samuel de Champlain monument on Nepean Point, for example, drew attention to the sculpture of an Anishinābe warrior at the explorer’s feet and resulted in a move to place the statue at its own site.

Thomas also began to engage with and challenge stereotypes in national cultural institutions. He researched how Indigenous peoples were represented in official Canadian records, and in 1994 he was hired by the National Archives to develop appropriate captions to replace outdated terms used in photographic descriptions. In 1996, Thomas co-curated Aboriginal Portraits from the National Archives of Canada with archivist Edward Tompkins, and in 2002 he organized the groundbreaking touring exhibition Where Are the Children? Healing the Legacy of the Residential Schools, also with the National Archives.

He has gone on to engage in numerous other curatorial projects across the country, as well as in the United States, and has represented Indigenous concerns as a board member for Gallery 101, Artengine, and the Ottawa Art Gallery, and in other roles for major cultural organizations, including the Ontario Arts Council and the Canada Council for the Arts. He has continued to create his own work to challenge the erasure of Indigenous people in urban space, often through the depiction of figurines in cities, as can be seen in Ottawa, Ontario, Peace Chief at the Peace Tower, c.2003, and Buffalo Robe—Happy Canada Day, Ottawa, 2013.

Thomas has been a powerful force in engaging with Canada’s shameful treatment of Indigenous peoples in the past and its failure to face issues of Indigenous life today. In his words, his “career began with a goal of weaving a new story from the fragmented cultural elements left in the wake of North American colonialism.” He has influenced the work of many younger Indigenous artists, including Meryl McMaster (b.1988) and Jamie Koebel. His work and his presence in the Ottawa scene have had a major impact on the nature of the city and its development.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements