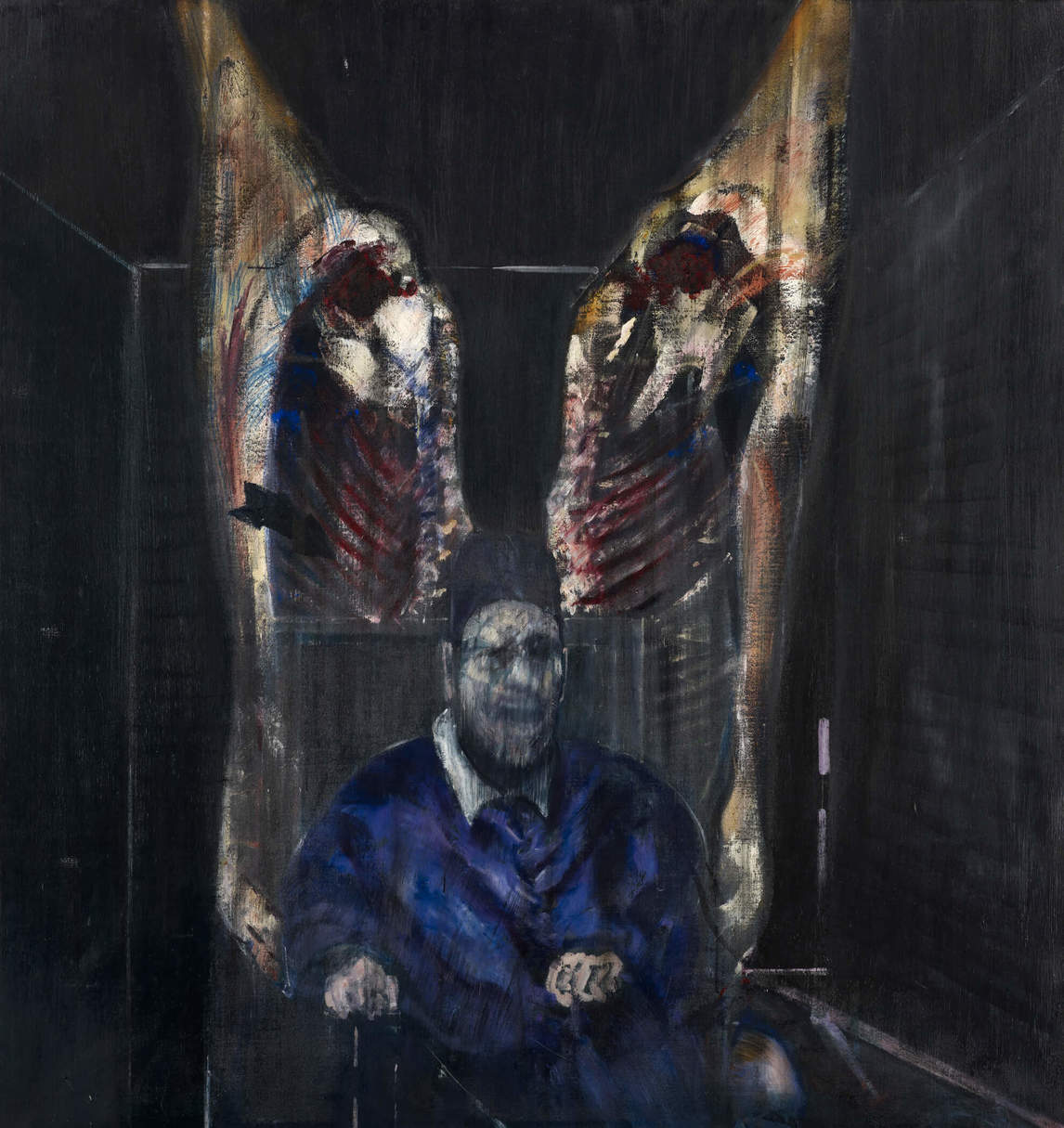

Service Station 1978

Mary Pratt, Service Station, 1978

Oil on Masonite, 101.6 x 76.2 cm

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Curator Mayo Graham of the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, first saw Mary’s paintings inadvertently on a studio visit with Mary’s husband, Christopher. Graham later included Mary in a nationally touring exhibition, Some Canadian Women Artists, and championed the purchase of one of Mary’s works, Red Currant Jelly, 1972, for the National Gallery’s permanent collection. On a studio visit with Mary in Salmonier in 1976, Graham encouraged her to make a painting from a slide Graham found in Mary’s collection of images that she hadn’t used for paintings: a butchered moose hung on the back of a tow truck. Pratt didn’t take the advice right away but did return to the slide in 1978 and painted Service Station, now in the collection of the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto.

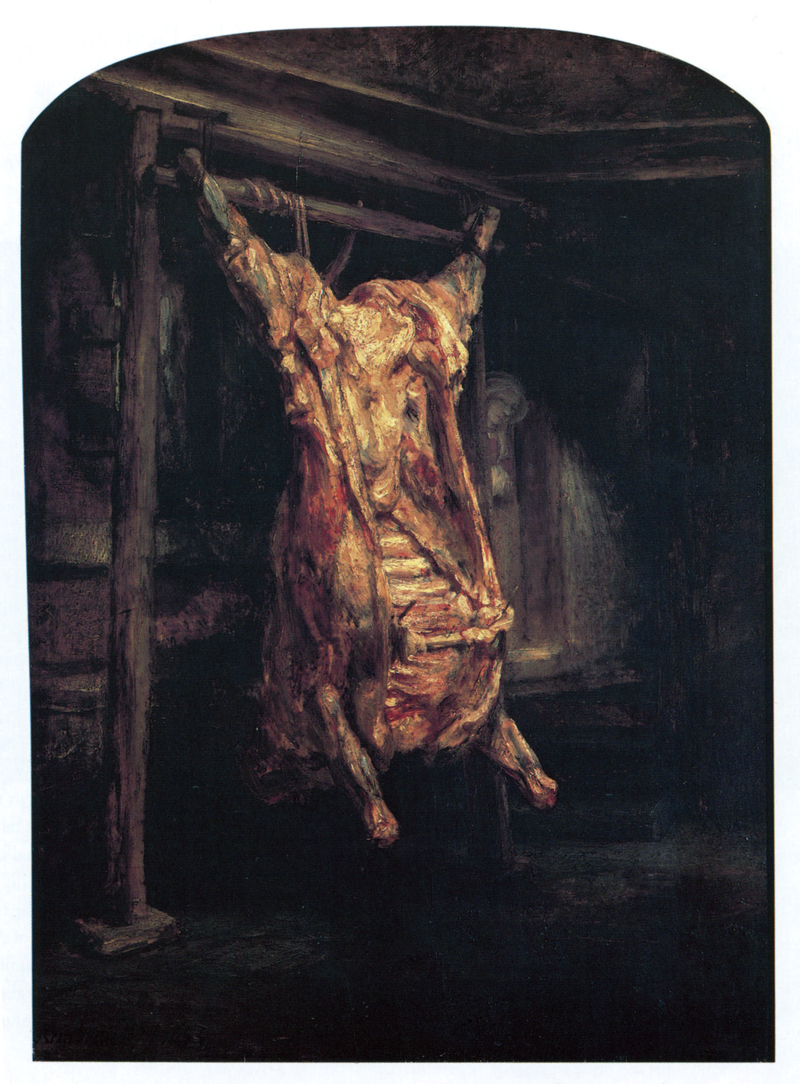

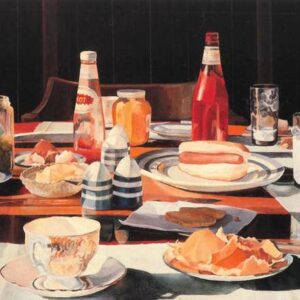

This is one of Pratt’s most powerful—and toughest—paintings, given its evocations of sexualized violence. The work could be compared to other painted slabs of meat by male artists like Chaim Soutine and Francis Bacon, suggesting the more horrific aspects of life and death—though unlike these painters, Pratt lends her carcass an unsettling degree of painterly control, as if she is unafraid to look at it (and daring us to). Service Station received critical accolades when it was first shown in a commercial exhibition in Toronto, and has been included in most of Pratt’s museum exhibitions. It was painted after an extended period of turmoil in her life. As she told Sarah Milroy, “We had lost the babies, then John got sick”—her son had a brief skirmish with cancer—“and I got through that, and then I said to myself: you can do this now. You know what this is about.”

The subtexts present in Pratt’s other work—sacrifice and violence—are laid out here directly. Pratt acknowledges that such images are common enough in rural Canada, and anywhere people hunt for their food, but little is read into them beyond an appreciation of the amount of meat the carcass is likely to provide.

This moose had been killed by Ed Williams, the owner of the Pratts’ local service station, who, knowing of Mary’s paintings of fish and chickens, asked her if she wanted to see his moose. “He had no idea that I would be upset by this moose. But to me it screamed ‘murder, rape, clinical dissection, torture,’ all the terrible nightmares hanging right in front of me.” Pratt’s neighbours saw less drama in such scenes. With her usual humour, she recalled much later to Sarah Milroy that when Williams saw the work, “He stood there in my studio looking at it for a moment, and then he shook his head and said, ‘Well, there’s my old truck.’”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements