No evidence exists of Louis Nicolas having had a formal training in art. However, he developed his own distinctive style of pen-and-ink drawing—detailed and energetic—and worked with seventeenth-century techniques of building compositions from engravings he found in natural history books. Although art by Nicolas appears simplistic and crowded compared to other works of his time, his sketches are usually accurate, though they can be fanciful too.

An Untrained Style

As a Jesuit priest, Louis Nicolas received a first-rate classical education focused on philosophy and languages. At the time, the Jesuit Order was renowned for its mathematical and science studies, but not for training in art. We can only guess how some of Nicolas’s artistic Jesuit contemporaries developed their natural talent and received their training. We know that some Jesuit missionaries in New France, such as Jean Pierron (1631–1700) and Claude Chauchetière (1645–1709), painted religious scenes to use in their efforts to convert Indigenous peoples, though no images by them have survived. One anonymous oil painting from the period shows a chained man engulfed in flames. An inscription written in Algonquin in the lower right of the canvas reads: “Look at me. See how I suffer in these flames. You will suffer the same if you don’t convert. Suffer during your lifetime; courage as long as you are on earth.”

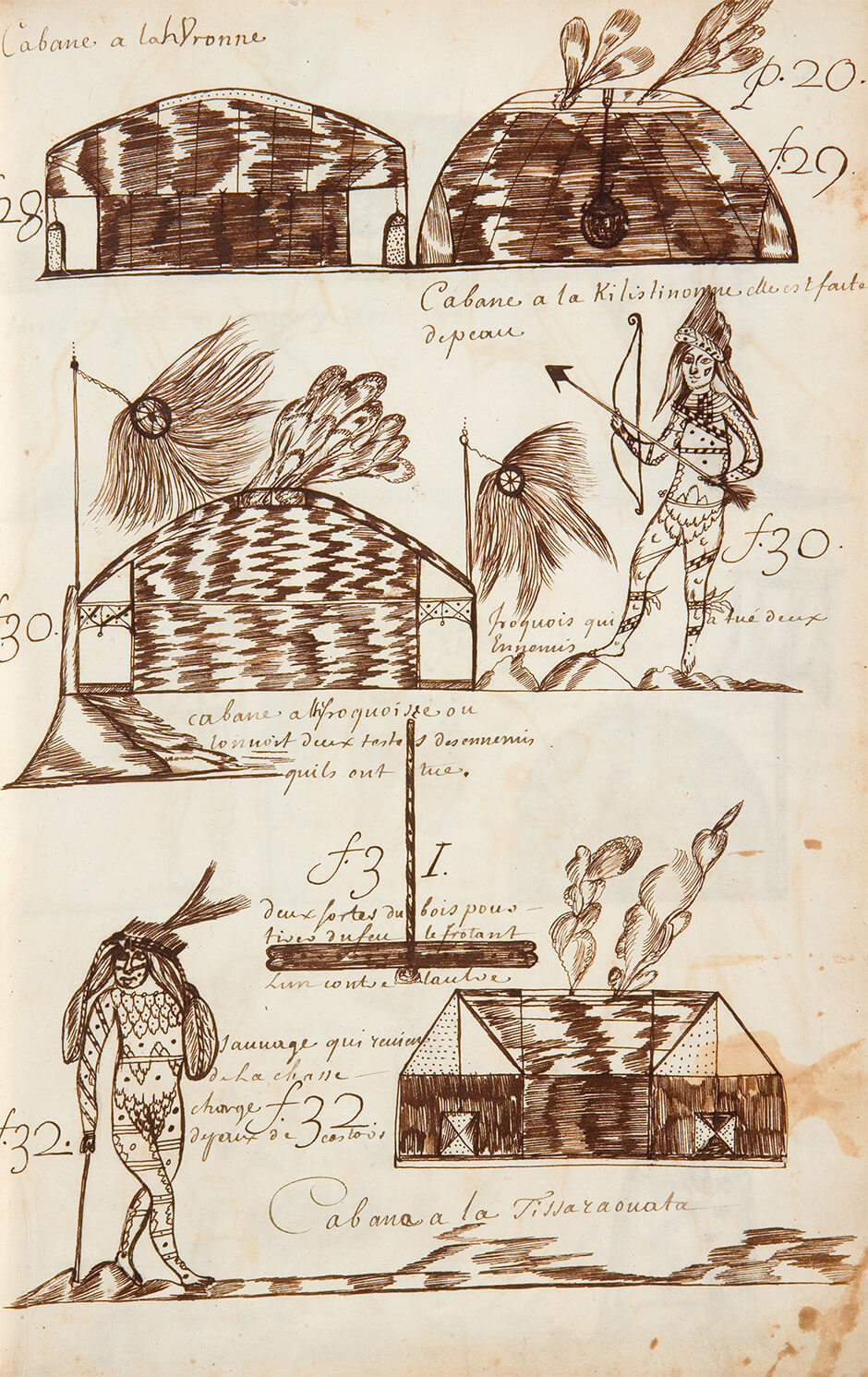

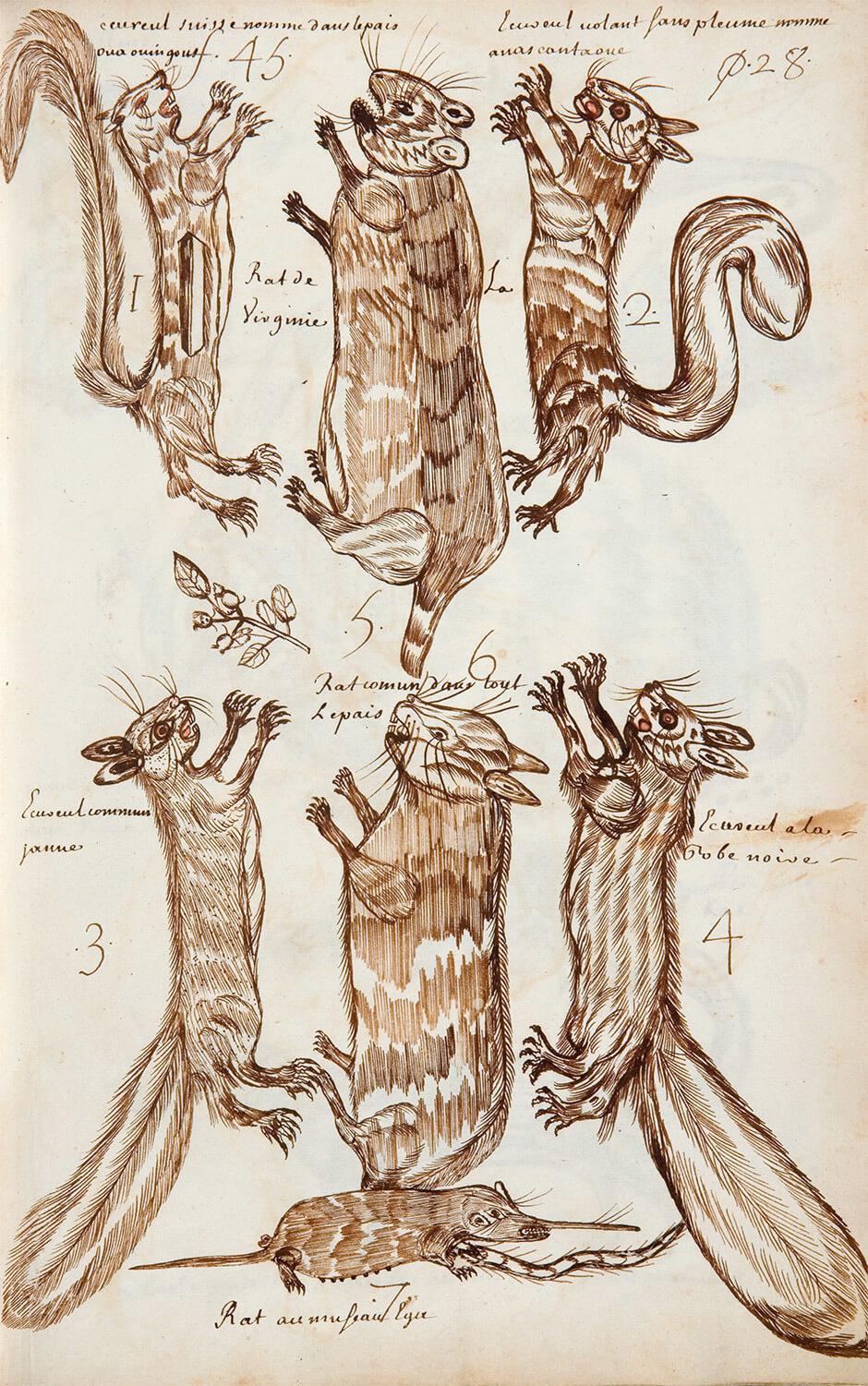

There is no mention in the Jesuit Relations (Relations des Jésuites), the volumes recording the missionary endeavours in New France, of Nicolas using art in his work, though he did accompany Pierron to his mission in Iroquois territory. Judging by the only artwork that exists from Nicolas’s hand, the drawings of the Codex Canadensis in the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma, it appears that Nicolas had little, if any, formal training in art. His sketches of Indigenous peoples engaged in their daily activities lack the skills of a trained seventeenth-century artist—techniques such as a proper use of perspective and a sophisticated use of light and dark shading to render drama. However, Nicolas was a talented and idiosyncratic amateur. In his enthusiasm to record as many examples as he could for his readers, he filled his pages with aesthetically original and pleasing sketches. These compositions, which face in a variety of directions, are more like trophies than observations from nature.

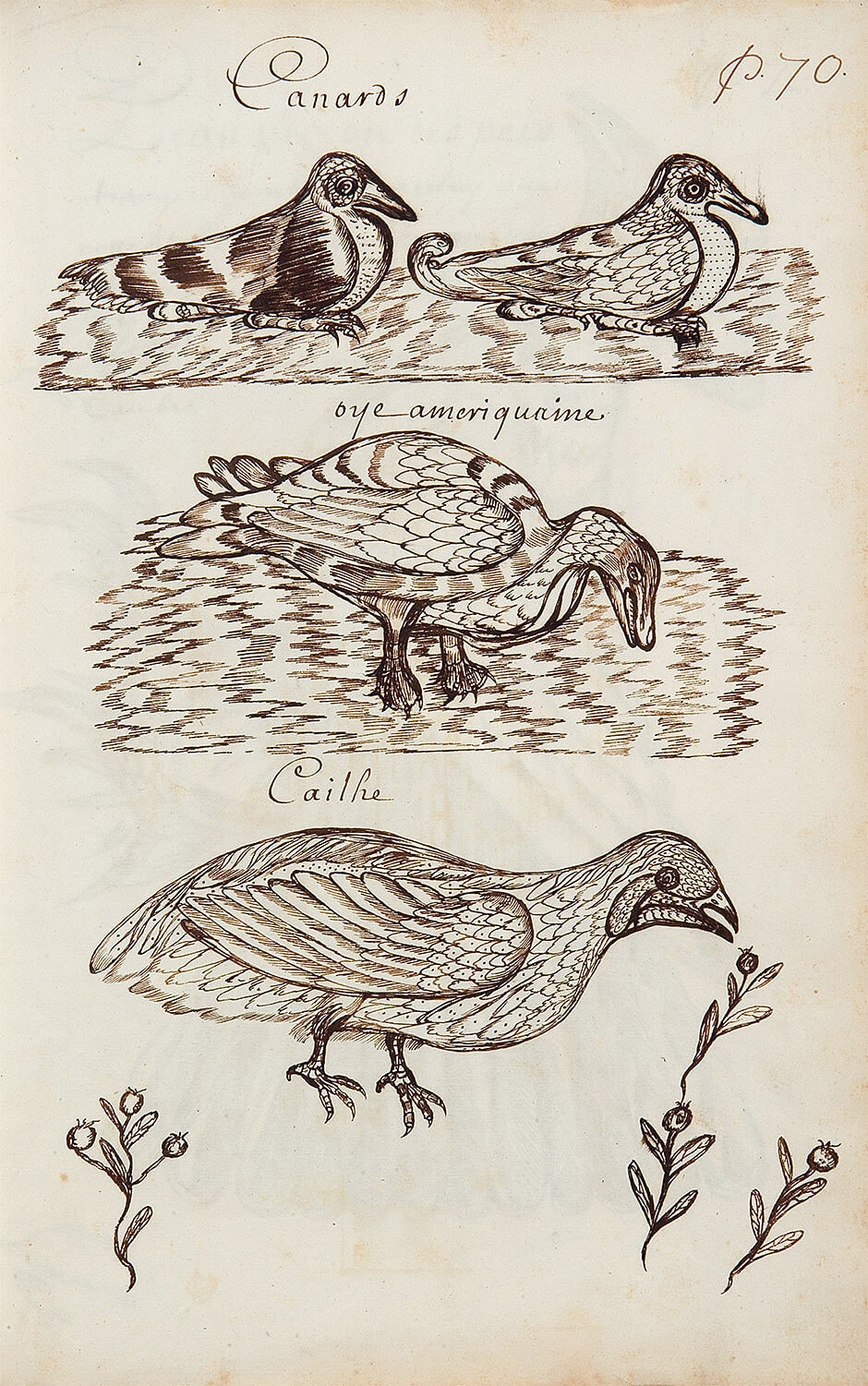

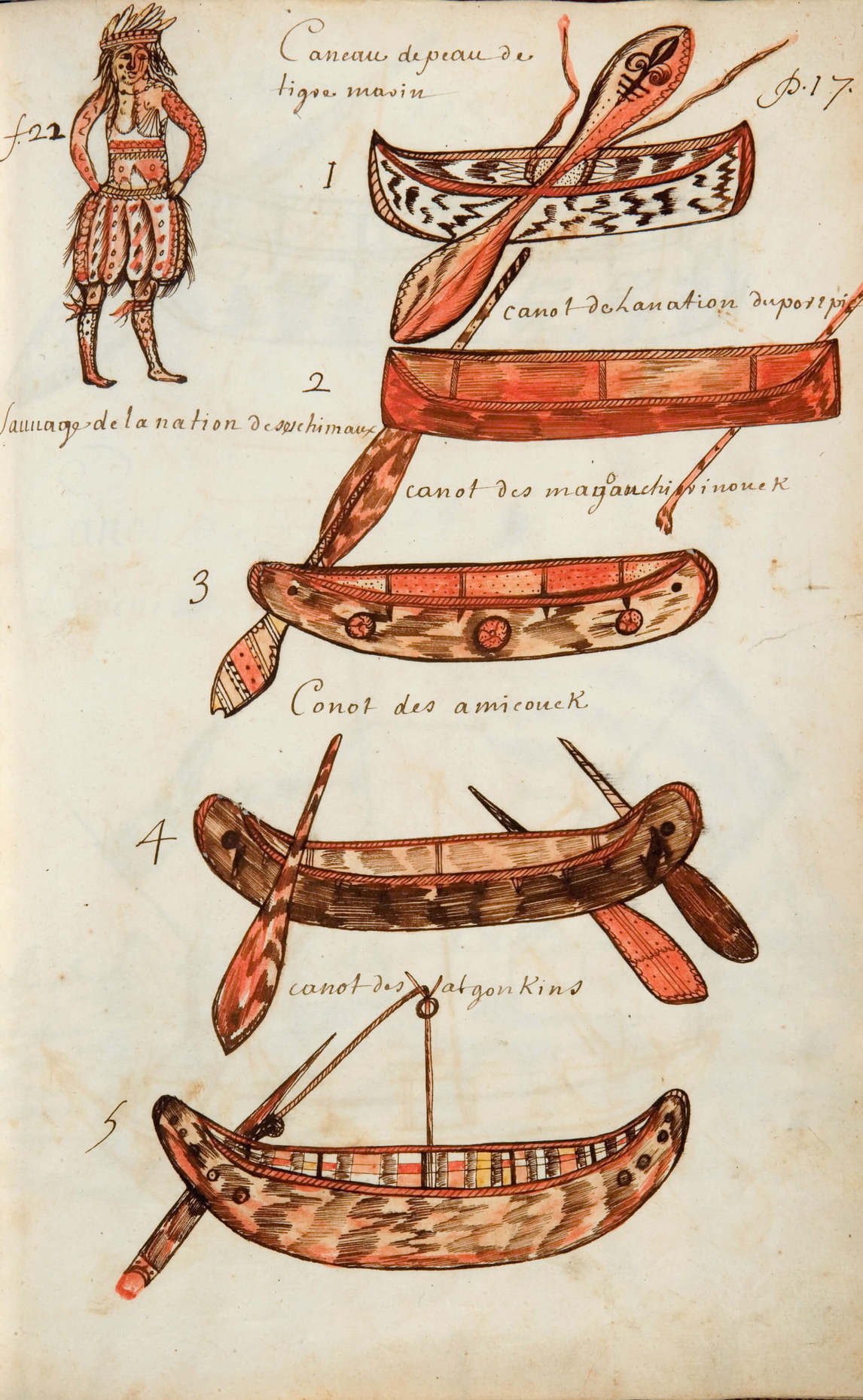

Throughout the Codex Canadensis, Nicolas’s drawings are consistent and do not reveal any significant evolution in style. They were probably created over a relatively short span of time in the 1690s and were bound together in the same volume. Yet every detail is carefully rendered in pen and ink, whether the paint on men’s bodies, the webbing on snowshoes, the scales on fish, the hairs on seals, the plumes on birds, or the long, flowing tails of the horses. Moreover, Nicolas frequently worked with signature techniques, including cross-hatching, which he used to give his figures a three-dimensional look. He also favoured a zigzag pattern to depict ripples in water or fur and feathers, as in his drawings of owls.

Colour is another attribute used in a few of the sketches. For example, Nicolas (or perhaps someone else later) tinted the drawings of amphibians with blue watercolour, to make clear they could live in water, and added bright red tongues to a few of the animals. The opening page of the section on birds has particularly vivid hues. The red heart that appears on the wing of the “Characaro” on another of the pages in this section is obviously an artistic rendition of the red patch formed by the bird’s feathers.

Engravings by Others as Models

Evidence indicates that the drawings in the Codex Canadensis were created after Nicolas returned to France in 1675—most likely during the 1690s. He never refers to any sketches that he made in New France. Rather, in Book Nine of The Natural History of the New World (Histoire naturelle des Indes occidentales), he writes that he wished he had “deeply imprinted in [his] imagination” all the animals he “has observed … on the sea, on lakes, on rivers, on land, and on the trees of America.”

Possibly to compensate for the lack of preparatory sketches, he drew the scenes of Indigenous life from memory. When necessary, especially for the “portraits” of kings or captains of various nations—for example, his King of the Great Nation of the Nadouessiouek (Roy de La grande Nation des Nadouessiouek), n.d.—he took the outlines from the engravings he found in the History of Canada, or of New France (Historiae Canadensis seu Novae Franciae Libri Decem) (1664) by Father François Du Creux (1596–1666).

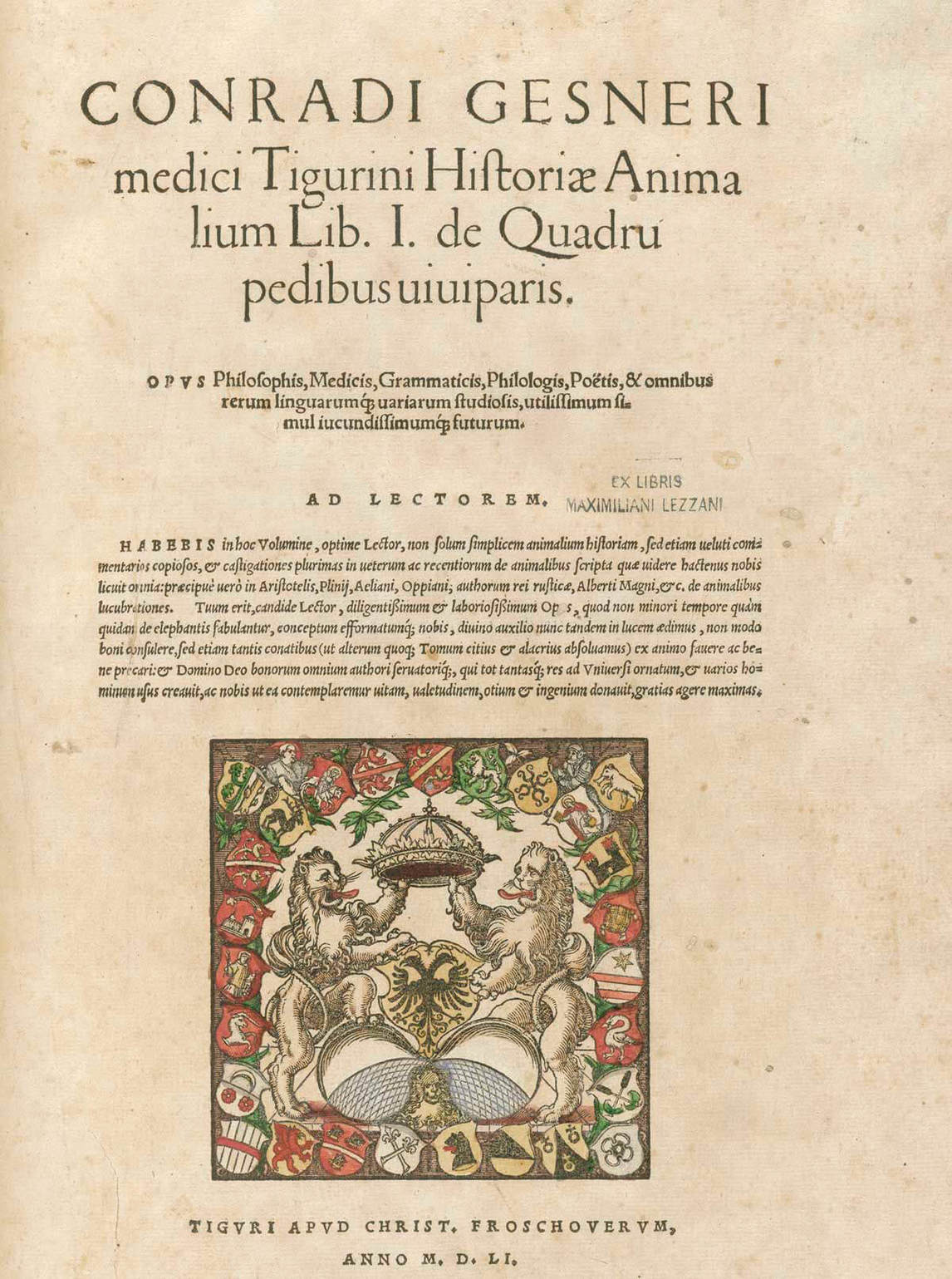

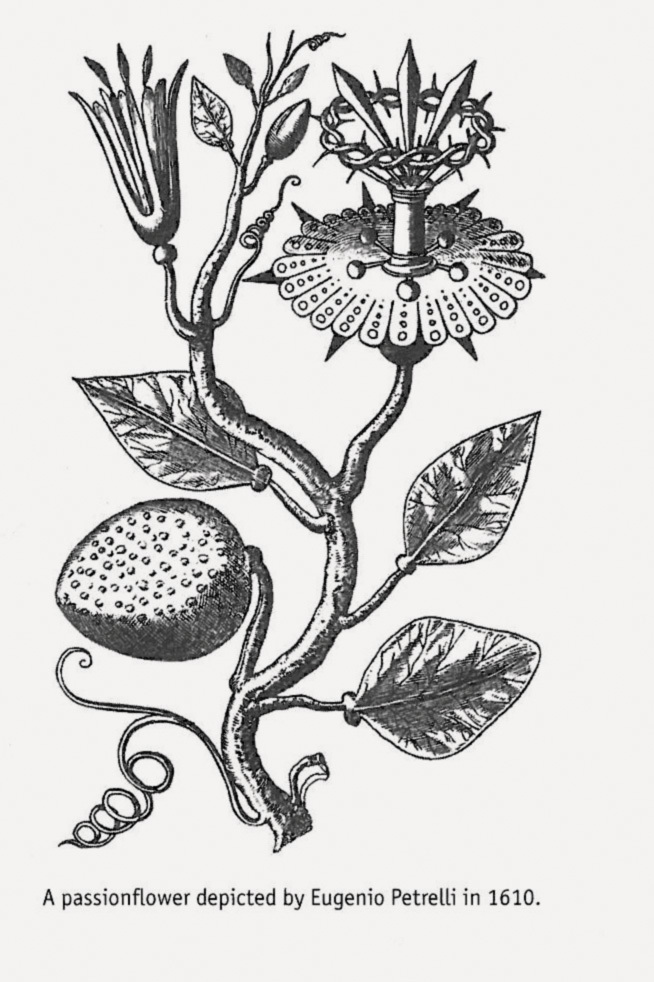

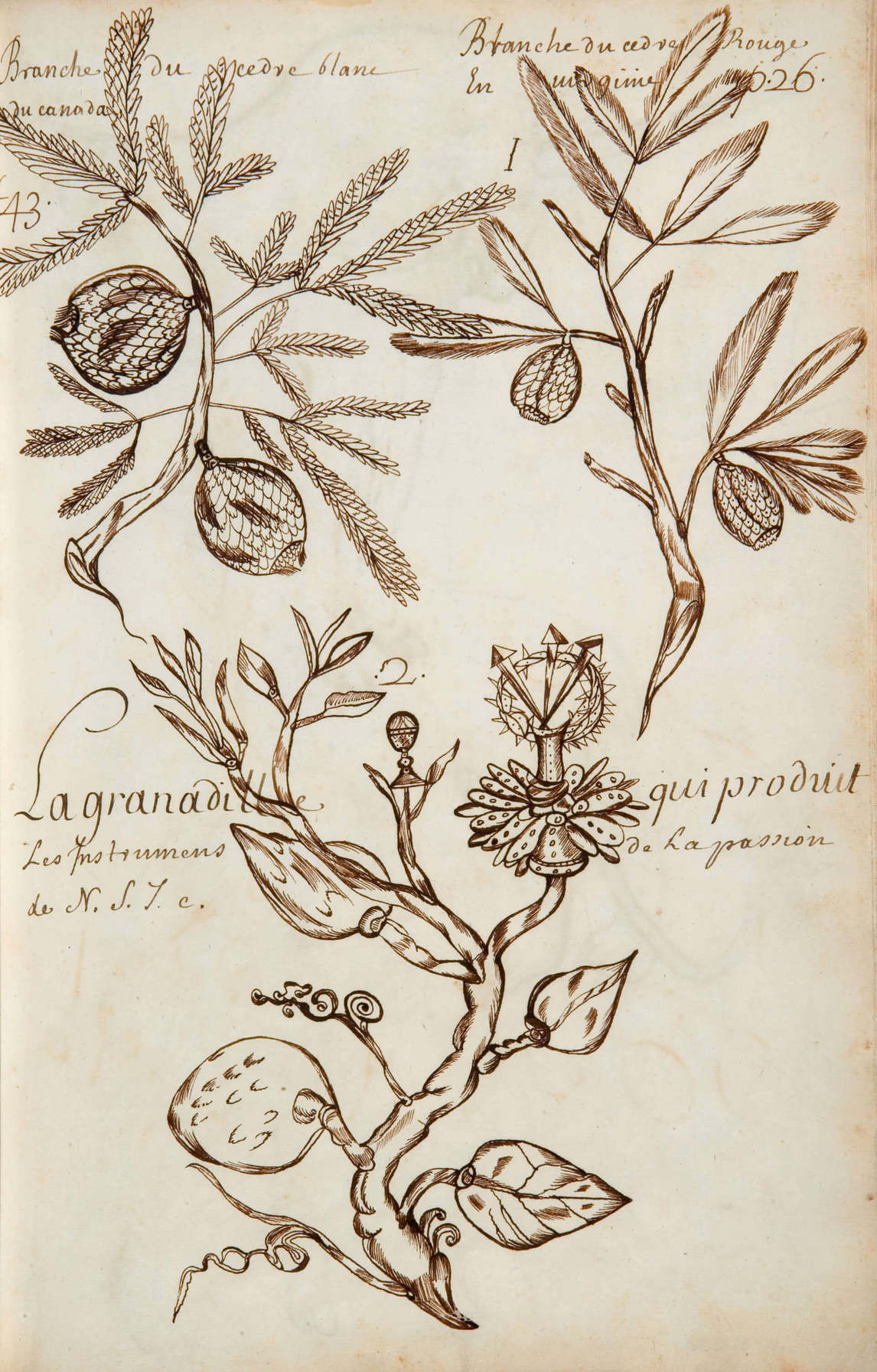

The five volumes of The History of Animals (Historiae Animalium) (1551–58, 1587) by Conrad Gessner (1516–1565) may also have helped Nicolas recognize the animals he had seen in Canada. He likely drew on those engravings to create his own versions of them—for example, his otter and beaver. The only exception to this technique seems to be his depiction of plants. As source material, Nicolas turned to the vegetation available in gardens in France for many of his examples. Likely using European models combined with the memories of what he had seen in North America, Nicolas created an inventory of plant drawings for the Codex. Occasionally, however, as for the passion flower (passiflora), Nicolas was influenced by published illustrations.

Nicolas was not alone in operating this way: in the late seventeenth century, most natural history illustrators worked from published examples, embellishing them with their own artistic flourish. Although he copied some compositions and ideas from the engravings he found in books, the details he added make his illustrations look quite different from the models that inspired him. His Noupiming warrior, for instance, though based on Du Creux’s warrior, is holding a hatchet rather than a pipe and wears no magnificent cape. In general, Nicolas’s illustrations are more informative than the somewhat conventional models he followed: his Indigenous figures are painted, festooned with other decorative pieces, and surrounded by useful implements: tomahawks, shields, tobacco pouches, and bows and arrows.

Nicolas also used European animals and birds as his models and adapted them to the species he had seen in New France—as he did with his Papace, or Grey Partridge (Papace ou perdris grise), n.d., taken from Gessner’s ptarmigan, but now featuring a fantastic plumage around the head, throat, and tail. He also used the same source image to depict two different animals, as with the “Virginia rat” (Rat de La Virginie) and the “rat common in the whole country” (Rat commun dans tout Le pais), both on page 28 of the Codex. These two rats look remarkably similar, but one is smaller than the other and the ears and tails are different. Most important, Nicolas was willing to break with the tradition of creating stiff, isolated specimens and, instead, made his creatures look alive, whether sitting on the ground eating a fish, like his otter, or swimming in the water like his beaver.

Nicolas also turned to the maps of others as source material. The outline and some of the place names in his detailed second map, of “Manitounie” (the Mississippi region) are taken from Du Creux and from Collection of Voyages (Recueil de voyages) (1681) by Melchisédec Thévenot. But once again Nicolas has updated the information and added his own stamp through his drawings and lettering.

Pen, Ink, and Paper

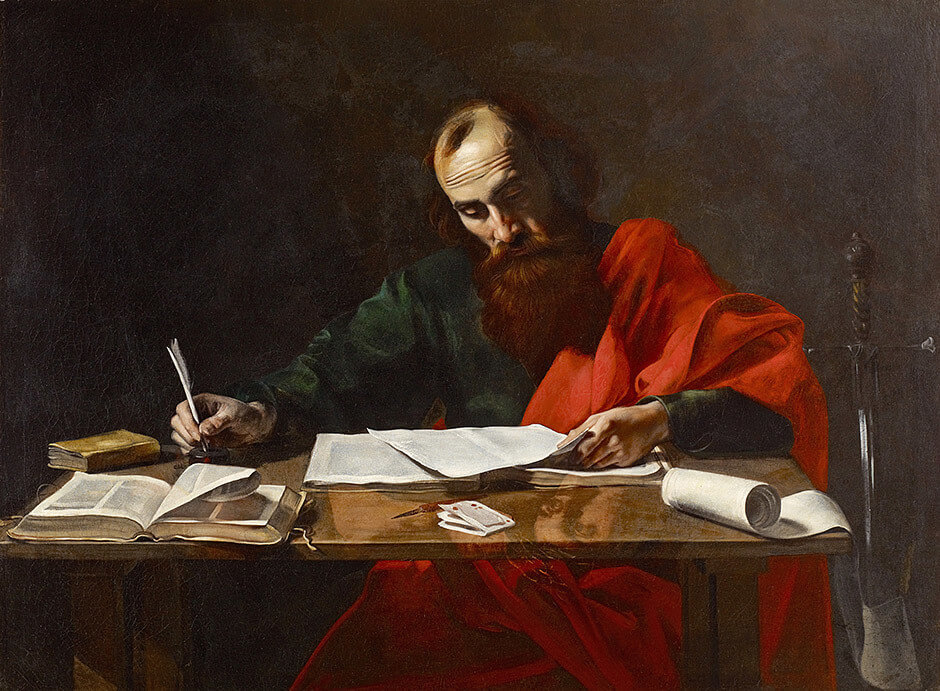

Nicolas made all his drawings in pen and ink—most likely using a feather quill (as the painter Valentin de Boulogne [1591–1632] depicted in his Saint Paul Writing His Epistles [Saint Paul écrit ses épîtres], c. 1616–20). The ink commonly used at the time was iron gall ink (also known as iron gall nut ink, oak gall ink, or common ink), made from iron salts and tannic acids. These acids came from a vegetable source, giving the ink a purple-black or brown-black colour. Over time, the ink has taken on a warm nutty-brown shade that is reminiscent of sepia, an ink derived from cuttlefish.

A few of the drawings are tinted in watercolour, or perhaps tempera, applied with a brush, as in Man of the Esquimaux Nation (Sauvage de la nation des eschimaux), n.d., and Large Ox of New Denmark in America (grand Boeuf du nouveau D’Anemar En amerique), n.d. As was customary at the time, the colouring may have been added by someone else at a later date. Whoever applied the colour did so sparingly: it always covers Nicolas’s usual elaborate pen-and-ink markings and is used on selected areas only, as in the grouping of canoes around Man of the Esquimaux Nation, or the brightly coloured assembly in Birds, n.d.

Nicolas would have created his drawings over many months if not a few years in the 1690s, but he chose his paper carefully—every page is exactly the same size and quality. He drew on separate sheets of folded paper, and when he took them all to a skilled bookbinder to have them bound into one volume, the craftsman sewed them together very tightly: the left edges on some of the images were caught in the central fold (where the paper is bound into the spine): on page 20, for example, the letter “f” before the figure numbers has almost disappeared. The paper that Nicolas used was made of linen, flax, or other vegetable material—a material that preserves well. The manuscript we know as the Codex Canadensis has the freshness of a recently completed book, despite its date.

Each individual page measures 33.7 by 21.6 centimetres—one half of a folded double page. Only one illustration—Cartier’s ship—occupies a full double page. Both of the maps were also drawn on double pages. They have no trace of any original stitching, but, rather, seem to have been “tipped in” to the spine—simply caught into the fold rather than stitched. Binders commonly treated maps in this way so they could be detached easily from the volume and mounted separately.

Binding the Codex

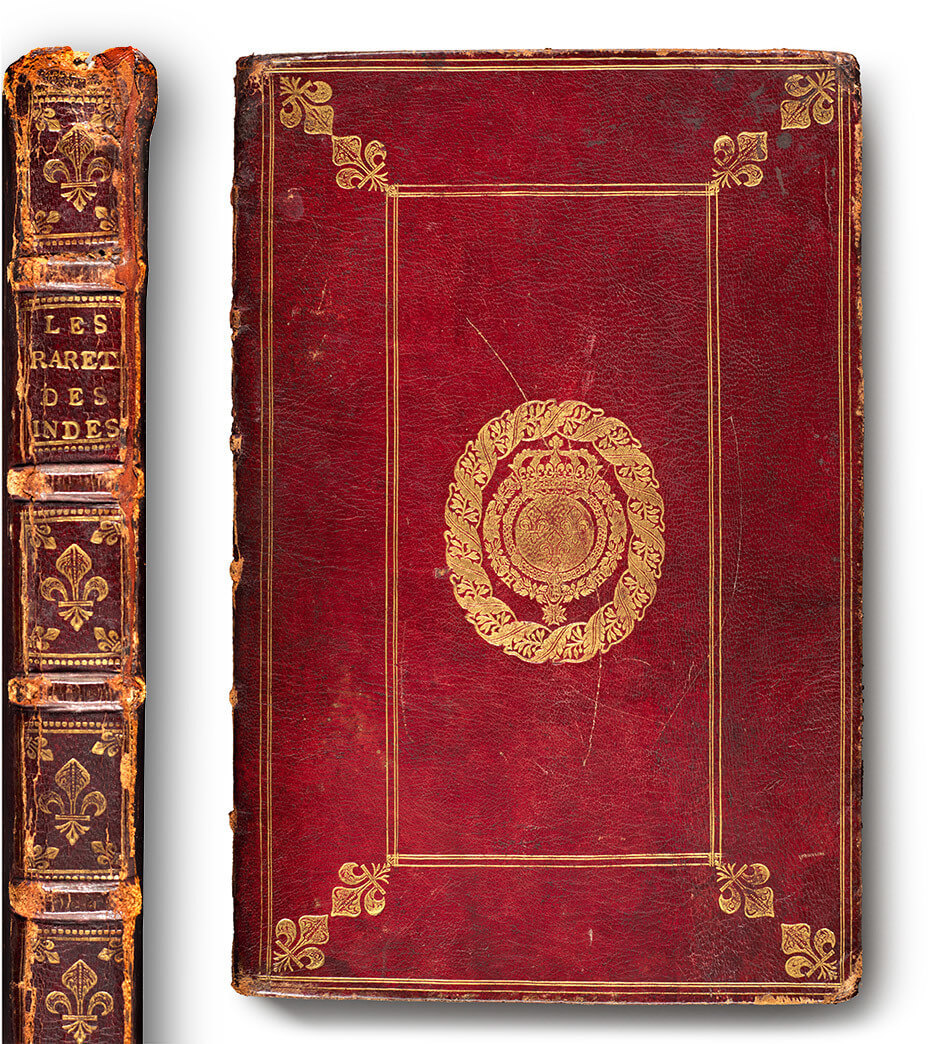

The Codex Canadensis’s binding is rich red leather decorated with gilded rules, fleurs-de-lys, and, in the centre of the front cover, the armorial stamp of Louis XIV. Did Nicolas choose this material himself? There have been suggestions that to make the album more valuable in the nineteenth-century French rare-book trade, someone had the original pages inserted into a royal binding that had been removed from another book. Such expert re-boxing (remboîtage) was quite common—and easy to accomplish for a book like this one with no known provenance.

Professor Germaine Warkentin has, however, studied the Codex at the Gilcrease Museum and, from her careful visual inspection, concluded that the present leather binding is likely the authentic original. In addition, she cites two pieces of evidence to support her view. First, the armorial stamp is the one Louis XIV used between 1688 and 1694 and probably later—close to the time when Nicolas must have devised the dedicatory pages. Second, given Nicolas’s earlier attempts to send gifts to the royal family and place himself in the king’s good graces, it is quite probable that, when he took his manuscript pages to the binder, he requested this particular design. At the time it was not unusual for petitioning authors to make formal presentations of their books to the monarch. Until we have expert evidence to the contrary, it’s safe to assume that the bound leather cover of the Codex Canadensis is the original one selected by Nicolas himself.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements